Date: 7 December 2006 | Season: Expanded Cinema 2006 | Tags: Expanded Cinema, Stuttgart

EXPANDED CINEMA: WORKSHOP

Thursday 7 December 2006, at 1pm

Stuttgart Württembergischer Kunstverein

KAREN MIRZA & BRAD BUTLER: CREATIVE PROJECTION

British artists Karen Mirza and Brad Butler will lead a practice-based workshop in creative projection that explores different approaches to EXPANDED CINEMA. Participants will be encouraged to experiment with unconventional modes of projection, and investigate the sculptural nature of film as a spatial and temporal medium.

Date: 3 April 2007 | Season: London Lesbian & Gay Film Festival 2007 | Tags: Jack Smith, Ken Jacobs, London Lesbian & Gay Film Festival

TWO WRENCHING DEPARTURES

Tuesday 3 April 2007, at 8pm

London Roxy Bar and Screen

Secret Cinema presents a free screening of a major new work by Ken Jacobs.

In his amazing live performances, Ken Jacobs breathed new life into archival film footage, teasing frozen frames into impossible depth and perpetual motion with two 16mm analytic projectors. Now aged 74, the artist explores new ways of documenting and developing his innovative Nervous System techniques in the digital realm.

Two Wrenching Departures, featuring the legendary Jack Smith (both clownish and devilishly handsome circa 1957), extends five minutes of material into a ninety-minute opus of eight movements. In and out of junk heap costume, Smith cavorts through the streets of New York (much consternation from the normals) and performs an impossible, traffic island ballet.

His improvised actions are transformed into perceptual games as Jacobs’ interrogates his footage, using repetition and pulsating flicker to open up new dimensions and temporal twists: The infinite ecstasy of little things. In commemorating two dear departed friends, with whom he collaborated on Blonde Cobra and other works, he propels their image into everlasting motion. These mindbending visions are juxtaposed with the soundtrack of The Barbarian, a 1933 Arabian fantasy starring Ramon Navarro and Myrna Loy, and music by Carl Orff.

TWO WRENCHING DEPARTURES

Ken Jacobs, USA, 2006, video, b/w, sound, 90 min

“In October 1989, estranged friends Bob Fleischner and Jack Smith died within a week of each other. Ken Jacobs met Smith through Fleischner in 1955 at CUNY night school, where the three were studying camera techniques. This feature-length work, first performed in 1989 as a live Nervous System piece is a ‘luminous threnody’ (Mark McElhatten) made in response to the loss of Jacobs’ friends.”

Ken Jacobs (born 1933) is one of the key figures of post-war cinema, whose films include Little Stabs at Happiness (1958-60), Blonde Cobra (1959-63), Tom Tom the Piper’s Son (1969-71), The Doctor’s Dream (1978), Perfect Film (1986) and Disorient Express (1995). He has also presented live cine-theatre (2D and 3D shadow plays) and developed the Nervous System and Nervous Magic Lantern projection techniques. Since 1999, Jacobs has primarily used electronic media, both in preserving his live performances and creating new digital works in a variety of styles. His 7-hour epic Star Spangled To Death (1957-2004) is now available on DVD from Big Commotion Pictures.

Free admission. No reservation necessary, but arrive early to avoid disappointment.Please note that this screening is not suitable for those susceptible to photosensitive epilepsy due to the extensive use of flickering and throbbing light.

Related Events

Ken Jacobs’ 1963 film Blonde Cobra will screen with Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures in the London Lesbian & Gay Film Festival on Saturday 31st March 2007 at 6.10pm.

Mary Jordan’s documentary Jack Smith and the Destruction of Atlantis also shows in the festival in the same day.

Back to top

Date: 13 April 2007 | Season: Swingeing London

SWINGEING LONDON

13-19 April 2007

Filmhuis Den Haag

For a few years after the Beatles first shook Britain out of the Dark Ages, it seemed like London was the place to be. Maybe the seeds of this cultural Renaissance were sown a little earlier, towards the end of the 1950s with the Free Cinema movement, and British Pop Art, first seen in “This Is Tomorrow” at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1956. Artist Richard Hamilton, who had created the iconic collage “Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing?” for that exhibition, produced a series of prints titled “Swingeing London”, which reproduced a newspaper photo of his hip gallerist Robert Fraser handcuffed to Mick Jagger following their arrest for drug possession in 1967. By this time, England’s capital city had been characterised as ‘Swinging London’ by Time Magazine, and the artist’s satirical play on words references the severity of the sentence bestowed on Fraser by the fearful establishment.

At the end of the decade, Hamilton collaborated with filmmaker James Scott on an eponymous self-portrait that perfectly encapsulates the artist’s spirit and sources of inspiration. The exuberant film is featured in this season which explores the embryonic counterculture that developed as ‘flower power’ blossomed and faded. As counterpoint to the feature films screening in the “Swinging London” series, “Swingeing London” excavates the underground.

It took the presence of a few key Americans in London to really get things cooking. William Burroughs lived in London from 1966-74, and had already made Towers Open Fire together with exploitation film distributor Antony Balch. The film remains the purest cinematic realisation of Burroughs’ distinct writing style. New Yorker Stephen Dwoskin was one of the founding members of the London Film-Makers Cooperative, and his fellow countryman Peter Gidal was a central figure of that organisation throughout the 1970s. Kenneth Anger lived in London after exiling himself from the US in 1967, a move prompted in part by his opposition (and fear) of the war in Vietnam, the same motive that brought Carolee Schneemann across the Atlantic. Another part-time Brit was Yoko Ono, who often resided in the apartment of artist John Latham, and famously bagged herself a Beatle.

With a little encouragement, the English shook off their innate reserve and embraced the new freedom and prosperity that modern life had to offer. London played host to several indicative and fundamental gatherings of the tribes – the International Poetry Congress at the Royal Albert Hall in 1965 (featuring Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti, Trocchi, documented in Peter Whitehead’s amazing verité Wholly Communion), the Destruction in Art Symposium (very little footage circulates from this 1966 performance series), and the Dialectics of Liberation psychology conference of 1967 (captured in the documentary Anatomy of Violence by Peter Davis). The music scene was a central focus, with concerts such as the 14 Hour Technicolor Dream Festival at Alexandra Palace (1967) and the free Rolling Stones show in Hyde Park (1969).

As portable 16mm equipment made cinema a more affordable and impulsive medium, many of these events were documented on film. As in the USA, where Andy Warhol, Jonas Mekas, Bruce Conner and others were already using cinema as a mode of personal artistic impression, British filmmakers soon moved in this direction. Inspired by a similar organisation in New York, the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative was founded by a group of enthusiasts in 1966. Initially a film society that met in the basement of the progressive Better Books shop to view the classics of world cinema (this is before alternative distribution circuits, vhs or dvd), the LFMC soon developed into a dynamic centre for the exploration of film as an art medium under the guidance of Dwoskin, Gidal, Malcolm Le Grice and others.

During this formative period ‘underground films’ were often to be seen projected before or during concerts by bands such as the Pink Floyd or Soft Machine at the UFO (Unlimited Freak Out) club or at all-night raves in the dilapidated Roundhouse. Artists Mark Boyle and Joan Hills (of the Boyle Family) formed the Sensual Laboratory, developing their experimental slide shows, which were already being performed in an art context, into full-blown complements to psychedelic rock concerts. Unlike the American light shows, Boyle and Hills’ visuals operated independently of the music, rather than being a synchronous, visual accompaniment to it.

Photographer John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins, a legendary figure on the London scene, was a founder member of IT (the counterculture newspaper International Times), UFO, the Notting Hill Festival and the London Free School. Despite this central organising role, he spent the Summer of Love in jail for marijuana possession. The recently rediscovered short film Poem for Hoppy shows Soft Machine and the Sensual Laboratory collaborating on an improvised howl of support.

After his release, Hoppy turned to the new medium of video, using one of the earliest Sony Portapaks. Working together with the TVX collective, he attracted the attention of the BBC and was invited into the studios of Television Centre to perform a live videomix happening with a group of artists, musicians and freaks. Videospace was not broadcast, but a surviving excerpt demonstrates some of the visual invention and playful creativity that took place at this unique event. Lutz Becker also experimented with the new video technology, creating feedback loops for Horizon, a work covered in detail in Gene Youngblood’s book “Expanded Cinema” but rarely seen today.

Though psychedelia dominated the pop scene, few films made in England in the sixties could truly be described as psychedelic. Mare’s Tail is a prime exception – a long, strange trip into inner space made by maverick filmmaker and photographer David Larcher. Mare’s Tail is a two and a half hour, abstract journey deep within. It was the first film shown in the cinema at the New Arts Lab (aka the Institute for Research in Art and Technology), where it ran for two successful weeks.

The original Arts Lab, on Drury Lane in the heart of Covent Garden, had been established by Jim Haynes and Jack Henry Moore in 1967. Incorporating a café, bookstore, gallery, theatre and cinema within a single building, the Arts Lab provided a venue and meeting point for different artistic groups. Haynes, another American who galvanised London’s counterculture, was also a co-founder of International Times and the Amsterdam based sexual freedom newspaper SUCK! All scenes feed into eachother.

The naïveté and optimism of this underground explosion didn’t last for long. In the US, Woodstock failed to live up to its promise and Altamont turned the hippie dream into a homicidal nightmare. England had Phun City and the Isle of Wight Festivals: No fatalities, but they were disastrously organised and showed that the idealistic hopes of the sixties generation were unsustainable without some form of structure to balance the spontaneity. As the ‘white heat of technology’ cooled down, unemployment set in and, during the seventies, glitter was liberally applied to cover the cracks in the youth culture.

SWINGEING LONDON 1: Sat 14 Apr & Tue 17 Apr 2007

SWINGEING LONDON 2: Sun 15 Apr & Wed 18 Apr 2007

SWINGEING LONDON 3: Sun 15 Apr & Thur 19 Apr 2007

SWINGEING LONDON 4: Fri 13 Apr & Mon 16 Apr 2007

SWINGEING LONDON is curated by Mark Webber.

Back to top

Date: 25 April 2007 | Season: Swingeing London

SWINGEING LONDON: THE SIXTIES UNDERGROUND

A Touring Programme from Filmhuis Den Haag

Wednesday 25 April 2007, Utrecht ‘t Hoogt

Sunday 29 April 2007, Rotterdam Lantaren/Venster

Tuesday 8—Wednesday 9 May 2007, Amsterdam Filmmuseum

Monday 14 May 2007, Arnhem Filmhuis

Soon after the Beatles first shook England out of the Dark Ages, it seemed like “Swinging London” was the place to be. The cultural Renaissance that had begun in the late 1950s, with the Free Cinema movement and British Pop Art, exploded across the nation and for a few years it seemed that anything was possible. Under the surface of the mainstream, an underground counterculture challenged the conventions of music, literature, art and filmmaking.

This programme shows how the influence of American Beat culture prompted British experimentation with media, ranging from the appearance of William Burroughs in Towers Open Fire to an unseen psychedelic happening inside the BBC TV studios. The films date from a time when artists created a new language of looking, and include music by Soft Machine, the Beatles and the Troggs.

Antony Balch & William Burroughs, Towers Open Fire, UK, 1963, 16 min

Michael Nyman, Love Love Love, UK, 1967, 5 min

Boyle Family, Poem for Hoppy, UK, 1967, 4 min

John Hopkins / TVX, Videospace Reel, UK, 1970, 15 min

Stephen Dwoskin, Naissant, UK, 1964-67, 14 min

John Latham, Talk Mr Bard, UK, 1968, 7 min

Simon Hartog, Soul in a White Room, UK, 1968, 3 min

Malcolm Le Grice, Reign of the Vampire, UK, 1970, 15 min

SWINGEING LONDON is curated by Mark Webber and takes its title from Richard Hamilton’s series of prints depicting Mick Jagger and Robert Fraser on their way to court, where they were convicted for the possession of illegal substances.

PROGRAMME NOTES

SWINGEING LONDON: THE SIXTIES UNDERGROUND

A Touring Programme from Filmhuis Den Haag

TOWERS OPEN FIRE

Antony Balch & William Burroughs, UK, 1963, 16mm, b/w, sound, 16 min

The remarkable Towers Open Fire was conceived by filmmaker and exploitation film distributor Antony Balch and “Naked Lunch” author William Burroughs, and features appearances by their associates Ian Sommerville, Brion Gysin and Alexander Trocchi. Envisioned as a cinematic realisation of Burroughs’ key themes, such as the breakdown in control, the film contains rapid editing, flicker, strobing and extreme jump cuts that interrupt the narrative flow. A brief passage of hand painted colour was applied to each print (during Mikey Portman’s dance sequence), and the film includes footage of the prototype Dreamachine, designed by Gysin to stimulate the brain’s alpha waves and aid hallucination. The British Censor requested removal of some offensive language from the soundtrack but passed (or failed to notice) the shots of Balch masturbating, and of Burroughs shooting up.

“Society crumbles as the Stock Exchange crashes, members of the Board are raygun-zapped in their own boardroom, and a commando in the orgasm attack leaps through a window and decimates a family photo collection …” (Tony Rayns, Cinema Rising, 1972)

LOVE LOVE LOVE

Michael Nyman, UK, 1967, 16mm, b/w, sound, 5 min

Hyde Park, 16th July 1967: Thousands attended the Legalise Pot Rally, a love-in to demonstrate the need for a relaxation of England’s strict drug laws. Love Love Love, made by composer Michael Nyman, is a pixillated record of the event with an obligatory Beatles soundtrack. The film features poet Allen Ginsberg, playwright Heathcoate Williams and artist David Medalla (leader of performance group The Exploding Galaxy). The peaceful protest was organised by SOMA (Society of Mental Awareness), who, one week later, placed a full page notice to argue their case in the Times newspaper. The advertisement was paid for by Paul McCartney and signed by 65 luminaries from both the underground and the establishment. Widely assumed to be timed in protest against the recent conviction of Jagger and Richards, the advert was more directly prompted by the swingeing sentence passed on John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins, who received nine months in prison for possession of a small quantity of pot.

POEM FOR HOPPY

Boyle Family, UK, 1967, 16mm, colour, sound, 4 min (shown on video)

An improvised performance, by Soft Machine and the Sensual Laboratory, in protest against John Hopkins’ conviction for marijuana possession.

“Mark Boyle and Joan Hills lived in and around Ladbroke Grove in the middle 1960s, organising events and making sculptures that attempted to present reality as it is. The events included various projection pieces presenting physical and chemical change: boiling water, burning slides and bodily fluids that led to them being asked by Hoppy to do a presentation at the first night of the UFO club, where their liquid light of exploding colours became the main visual accompaniment to the bands that performed there. Pink Floyd, Soft Machine, Jimi Hendrix, the underground scene and psychedelic lightshows exploded out of UFO, across London and around the world.” (Portobello Film Festival)

VIDEOSPACE REEL

John Hopkins / TVX, UK, 1970, 16mm, colour, sound, 15 min (shown on video)

This recently rediscovered reel of early video image processing by John Hopkins and the TVX collective begins with a music “visualisation” made for the BBC to accompany the track “Scotland” by Area Code 615. The remaining footage is an excerpt from the Videospace happening which took place inside a BBC TV studio: an un-broadcast optical dub session which incorporated music, tape, film and feedback loops, lightshows, dancing, inflatables and live video mixing.

NAISSANT

Stephen Dwoskin, UK, 1964-67, 16mm, b/w, sound, 14 min

Dwoskin’s early films were heavily influenced by Warhol, in both the visual content and extended duration. They typically consisted of long takes from a fixed or hand-held camera, with an attractive young woman as the only protagonist. Composer Gavin Bryars provided the soundtrack to Naissant and several others.

“Objective location: a bed; subjective location: in thoughts. Being with thoughts and the child to be born. Camera from three sides of the bed with three lenses working from bed level and standing level. Filmed in New York in 1964, completed in London 1967. Naissant presents being alone with one’s thoughts. Time and her inner thoughts are found out only by spending time with her in the film.” (Stephen Dwoskin)

TALK MR BARD

John Latham, UK, 1968, 16mm, colour, sound, 7 min

Talk Mr Bard consists of the crude and rapid animation of a seemingly endless succession of coloured paper discs. The homemade soundtrack is a chaotic college of radio fragments and interference. A tutor at Saint Martins School of Art, Latham organised the protest Still and Chew in August 1966, for which he invited friends to chew pages from Clement Greenberg’s book “Art and Culture”, which had been borrowed from the college library. The soggy paper was spat out and fermented in a mixture of sulphuric acid, sodium bicarbonate and yeast. When he eventually received an overdue notice from the library months later, Latham encased the remaining liquid in a glass teardrop, which he labelled “Essence of Greenberg” and returned. He lost his job, but had the last laugh some years later by selling the residue of the event to the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

SOUL IN A WHITE ROOM

Simon Hartog, UK, 1968, 16mm, colour, sound, 3 min

LFMC founder member Simon Hartog was one of the most politically aware filmmakers of the period. This early short film is an amusing piece of social commentary on mixed race relationships, which were hardly commonplace in the UK at that time, and has a soundtrack by The Troggs. The male character played by Omar Dop-Blondin, a Sengelese student fresh from the Paris 68 protests, and an associate of the London Black Panthers.

REIGN OF THE VAMPIRE

Malcolm Le Grice, UK, 1970, 16mm, b/w, sound, 15 min

Le Grice’s work developed through direct processing, printing and projection, gaining an understanding of the material and exploring duration while touching on aspects of spectacle and narrative, and using early computer imagery. Reign of the Vampire addresses contemporary paranoia about the military-industrial complex, the Vietnam War, and the suspected influence of American government’s intelligence agency in countercultural activities. It was the last of a group of works shown together under the collective title “How to Screw the CIA, or How to Screw the CIA ?”

“This film could be considered as a synthesis of the series. It is formally based on the permutative loop structure, superimposing a series of three pairs of image loops of different lengths with each other. The images include elements from all the previous parts of the series. The film sequences that make up the loops are chosen for their combination of semantic relationships, and abstract factors of movement. The soundtrack is constructed for the film, but independently, and has a similar loop structure.” (Malcolm Le Grice)

Back to top

Date: 23 May 2007 | Season: Shoot Shoot Shoot 2006 | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT: EXPANDED CINEMA

Wednesday 23 May 2007, at 7PM

Wrexham Arts Centre

Beginning in the 1960s, artists at the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative experimented with multiple projection, live performance and film environments. In liberating cinema from traditional theatrical presentation, they broke down the barrier between screen and audience, and extended the creative act to the moment of exhibition. “Shoot Shoot Shoot” presents historic works of Expanded Cinema, for which each screening is a unique, collective experience, in stark contrast to contemporary video installations. In Line Describing a Cone, a film projected through smoke, light becomes an apparently solid, sculptural presence, whilst other works for multiple projection create dynamic relationships between images and sounds.

Malcolm Le Grice, Castle Two, 1968, b/w, sound, 32 min (2 screens)

Sally Potter, Play, 1971, b/w & colour, silent, 7 min (2 screens)

William Raban, Diagonal, 1973, colour, sound, 6 min (3 screens)

Gill Eatherley, Hand Grenade, 1971, colour, sound, 8 min (3 screens)

Lis Rhodes, Light Music, 1975-77, b/w, sound, 20 min (2 screens)

Anthony McCall, Line Describing A Cone, 1973, b/w, silent, 30 min. (1 screen, smoke)

Curated by Mark Webber. Presented in association with LUX.

PROGRAMME NOTES

SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT: EXPANDED CINEMA

Wednesday 23 May 2007, at 7PM

Wrexham Arts Centre

EXPANDED CINEMA at the LONDON FILM-MAKERS’ CO-OPERATIVE

Expanded Cinema is a term used to describe works that do not confirm to the traditional single-screen cinema format. It could mean having two (or more) images side-by-side on the screen, films that incorporate live performances or are projected in an unorthodox manner without a screen. Even light pieces that do not use any film at all. Some work demands that the filmmaker interact with the projected image, or be behind the projectors to alter their configuration throughout the screening.

The London Film-Makers’ Co-operative was an artist-led organisation formed in 1966, and uniquely incorporated a distribution office, workshop laboratory and screening room. Expanded Cinema continued the analytical exploration of the material that was conducted by filmmakers in the workshop, and emphasised the transient nature of the medium.

The Co-op’s cinema space was a flat, open room with no fixed seating. Filmmakers were free to experiment with projectors, demonstrating that the moment of exhibition can be as much a part of the work as the original concept, filming, editing and processing. The technology that puts the illusion of movement onscreen was no longer hidden away in a projection booth behind the audience, but placed amongst them.

In questioning the role of the spectator, Expanded Cinema challenged the conventions of the cinema event and introduced elements of chance and improvisation. Sometimes, what happened across the room was more important than what was up on the screen. With such work no two projections were ever the same: each screening was a unique, social, collective experience for the assembled audience.

This drive beyond the screen and theatre inevitably took the work into galleries, but only as a practical measure since open spaces and white walls were ideal for unconventional projection. The filmmakers made no attempts to commodify their work by producing editions, for many it was against their socialist principles. Though Expanded Cinema anticipated many recent trends in gallery-based moving image works and installations, there was little acceptance from the art world in the early years, or acknowledgement of this groundbreaking work today.

Mark Webber

CASTLE TWO

Malcolm Le Grice, 1968, b/w, sound, 32 min (2 screens)

“This film continues the theme of the military/industrial complex and its psychological impact upon the individual that I began with Castle One. Like Castle One, much use is made of newsreel montage, although with entirely different material. The film is more evidently thematic, but still relies on formal devices – building up to a fast barrage of images (the two screens further split – to give 4 separate images at once for one sequence). The images repeat themselves in different sequential relationships and certain key images emerge both in the soundtrack and the visual. The alienation of the viewer’s involvement does not occur as often in this film as in Castle One, but the concern with the viewer’s experience of his present location still determines the structure of certain passages in the film.” —Malcolm Le Grice, London Film-Makers’ Co-operative catalogue, 1968

“Le Grice’s work induces the observer to participate by making him reflect critically not only on the formal properties of film but also on the complex ways in which he perceives that film within the limitations of the environment of its projection and the limitations created by his own past experience. A useful formulation of how this sort of feedback occurs is contained in the notion of ‘perceptual thresholds’. Briefly, a perceptual threshold is demarcation point between what is consciously and what is pre-consciously perceived. The threshold at which one is able to become conscious of external stimuli is a variable that depends on the speed with which the information is being projected, the emotional charge it contains and the general context within which that information is presented. This explains Le Grice’s continuing use of devices such as subliminal flicker and the looped repetition of sequences in a staggered series of changing relationships.” —John Du Cane, Time Out, 1977

PLAY

Sally Potter, 1971, b/w & colour, silent, 7 min (2 screens)

“In Play, Potter filmed six children – actually, three pairs of twins – as they play on a sidewalk, using two cameras mounted so that they recorded two contiguous spaces of the sidewalk. When Play is screened, two projectors present the two images side by side, recreating the original sidewalk space, but, of course, with the interruption of the right frame line of the left image and the left frame line of the right image – that is, so that the sidewalk space is divided into two filmic spaces. The cinematic division of the original space is emphasized by the fact that the left image was filmed in color, the right image in black and white. Indeed, the division is so obvious that when the children suddenly move from one space to the other, ‘through’ the frame lines, their originally continuous movement is transformed into cinematic magic.” —Scott MacDonald, A Critical Cinema 3, 1998)

“To be frank, I always felt like a loner, an outsider. I never felt part of a community of filmmakers. I was often the only female, or one of few, which didn’t help. I didn’t have a buddy thing going, which most of the men did. They also had rather different concerns, more hard-edged structural concerns … I was probably more eclectic in my taste than many of the English structural filmmakers, who took an absolute prescriptive position on film. Most of them had gone to Oxford or Cambridge or some other university and were terribly theoretical. I left school at fifteen. I was more the hand-on artist and less the academic. The overriding memory of those early years is of making things on the kitchen table by myself…” —Sally Potter interviewed by Scott MacDonald, A Critical Cinema 3, 1998

DIAGONAL

William Raban, 1973, colour, sound, 6 min (3 screens)

“Diagonal is a film for three projectors, though the diagonally arranged projector beams need not be contained within a single flat screen area. This film works well in a conventional film theatre when the top left screen spills over the ceiling and the bottom right projects down over the audience. It is the same image on all three projectors, a double-exposed flickering rectangle of the projector gate sliding diagonally into and out of frame. Focus is on the projector shutter, hence the flicker. This film is ‘about’ the projector gate, the plane where the film frame is caught by the projected light beam.” —William Raban, Perspectives on British Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1977

“The first great excitement is finding the idea, making its acquaintance, and courting it through the elaborate ritual of film production. The second excitement is the moment of projection when the film becomes real and can be shared with the audience. The former enjoyment is unique and privileged; the second is not, and so long as the film exists, it is infinitely repeatable.” —William Raban, Arts Council Film-Makers on Tour catalogue, 1980

HAND GRENADE

Gill Eatherley, 1971, colour, sound, 8 min (3 screens)

“Although the word ‘expanded’ cinema has also been used for the open/gallery size/multi screen presentation of film, this ‘expansion’ (could still but) has not yet proved satisfactory – for my own work anyway. Whether you are dealing with a single postcard size screen or six ten-foot screens, the problems are basically the same – to try to establish a more positively dialectical relationship with the audience. I am concerned (like many others) with this balance between the audience and the film – and the noetic problems involved.” —Gill Eatherley, 2nd International Avant-Garde Film Festival programme notes, 1973

“Malcolm Le Grice helped me with Hand Grenade. First of all I did these stills, the chairs traced with light. And then I wanted it to all move, to be in motion, so we started to use 16mm. We shot only a hundred feet on black and white. It took ages, actually, because it’s frame by frame. We shot it in pitch dark, and then we took it to the Co-op and spent ages printing it all out on the printer there. This is how I first got involved with the Co-op.” —Gill Eatherley, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

LIGHT MUSIC

Lis Rhodes, 1975-77, b/w, sound, 20 min (2 screens)

“Lis Rhodes has conducted a thorough investigation into the relationship between the shapes and rhythms of lines and their tonality when printed as sound. Her work Light Music is in a series of ‘moveable sections’. The film does not have a rigid pattern of sequences, and the final length is variable, within one-hour duration. The imagery is restricted to lines of horizontal bars across the screen: there is variety in the spacing (frequency), their thickness (amplitude), and their colour and density (tone). One section was filmed from a video monitor that produced line patterns on the screen that varied according to sound signals generated by an oscillator; so initially it is the sound which produces the image. Taking this filmed material to the printing stage, the same lines that produced the picture are printed onto the optical soundtrack edge of the film: the picture thus produces the sound. Other material was shot from a rostrum camera filming black and white grids, and here again at the printing stage, the picture is printed onto the film soundtrack. Sometimes the picture ‘zooms’ in on the grid, so that you actually ‘hear’ the zoom, or more precisely, you hear an aural equivalent to the screen image. This equivalence cannot be perfect, because the soundtrack reproduces the frame lines that you don’t see, and the film passes at even speed over the projector sound scanner, but intermittently through the picture gate. Lis Rhodes avoids rigid scoring procedures for scripting her films. This work may be experienced (and was perhaps conceived) as having a musical form, but the process of composition depends on various chance operations, and upon the intervention of the filmmaker upon the film and film machinery. This is consistent with the presentation where the film does not crystallize into one finished form. This is a strong work, possessing infinite variety within a tightly controlled framework.” —William Raban, Perspectives on British Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1977

“The film is not complete as a totality; it could well be different and still achieve its purpose of exploring the possibilities of optical sound. It is as much about sound as it is about image; their relationship is necessarily dependent as the optical sound track ‘makes’ the music. It is the machinery itself which imposes this relationship. The image throughout is composed of straight lines. It need not have been.” —Lis Rhodes, A Perspective on English Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1978

LINE DESCRIBING A CONE

Anthony McCall, 1973, b/w, silent, 30 min (1 screen, smoke)

“Once I started really working with film and feeling I was making films, making works of media, it seemed to me a completely natural thing to come back and back and back, to come more away from a pro-filmic event and into the process of filmmaking itself. And at the time it all boiled down to some very simple questions. In my case, and perhaps in others, the question being something like “What would a film be if it was only a film?” Carolee Schneemann and I sailed on the SS Canberra from Southampton to New York in January 1973, and when we embarked, all I had was that question. When I disembarked I already had the plan for Line Describing a Cone fully-fledged in my notebook. You could say it was a mid-Atlantic film! It’s been the story of my life ever since, of course, where I’m located, where my interests are, that business of “Am I English or am I American?” So that was when I conceived Line Describing a Cone and then I made it in the months that followed.” —Anthony McCall, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

“One important strategy of expanded cinema radically alters the spatial discreteness of the audience vis-à-vis the screen and the projector by manipulating the projection facilities in a manner which elevates their role to that of the performance itself, subordinating or eliminating the role of the artist as performer. The films of Anthony McCall are the best illustration of this tendency. In Line Describing a Cone, the conventional primacy of the screen is completely abandoned in favour of the primacy of the projection event. According to McCall, a screen is not even mandatory: The audience is expected to move up and down, in and out of the beam – this film cannot be fully experienced by a stationary spectator. This means that the film demands a multi-perspectival viewing situation, as opposed to the single-image/single-perspective format of conventional films or the multi-image/single-perspective format of much expanded cinema. The shift of image as a function of shift of perspective is the operative principle of the film. External content is eliminated, and the entire film consists of the controlled line of light emanating from the projector; the act of appreciating the film – i.e., ‘the process of its realisation’ – is the content.” —Deke Dusinberre, “On Expanding Cinema”, Studio International, November/December 1975

Back to top

Date: 26 May 2007 | Season: Evolution 2007 | Tags: Aldo Tambellini, Evolution

ALDO TAMBELLINI: ELECTROMEDIA & THE BLACK FILM SERIES

Saturday 26 May 2007, at 3pm

Leeds Opera North Linacre Studio

As a key figure of the 1960s Lower East Side arts scene, Aldo Tambellini used a variety of media for social and political communication. In the age of McLuhan and Fuller, Tambellini manipulated new technology in an exploration of the “psychological re-orientation of man in the space age.” He presented immersive, multi-media environments and, having made his first experimental video as early as 1966, participated in early collaborations between artists and broadcast television.

His dynamic Black Film Series (1965-69) extends from total abstraction to footage of the assassination of Bobby Kennedy, the Vietnam War, and black teenagers in Coney Island. Tambellini worked directly on the film strip with chemicals, paint and ink, scratching, scraping, and intercutting material from industrial films, newsreels and TV. Abrasive, provocative and turbulent, the series is a rapid-fire response to the beginning of the information age and a world in flux. “Black to me is like a beginning … Black is within totality, the oneness of all. Black is the expansion of consciousness in all directions.”

“Electromedia was the fusion of the various art and media – breaking media away from it’s ‘traditional media role’ – bringing it into the area of modern art – bringing the others arts – poetry – sounds – painting – kinetic sculpture – into a time/space reorientation toward media – transforming both the arts and the media …” (Aldo Tambellini)

Aldo Tambellini will be present to introduce and discuss his early work in film and video.

Programme curated by Mark Webber for Evolution 2007. Programme repeated at Lucca Film Festival 30 September 2007.

PROGRAMME NOTES

ALDO TAMBELLINI: ELECTROMEDIA & THE BLACK FILM SERIES

Saturday 26 May 2007, at 3pm

Leeds Opera North Linacre Studio

A true intermedia activist, Aldo Tambellini was a key figure of the Lower East Side arts scene, working in sculpture, painting, poetry, film, video and theatre. Believing it was “no longer sufficient for the creative individual to remain in isolation,” he co-founded the alternative arts community Group Center in 1960. After publishing counterculture newsletters and making early happenings to protest against the art establishment (such as presenting The Golden Screw Award to the Museum of Modern Art), Tambellini embraced new technology as a tool to explore the “psychological re-orientation of man in the space age.”

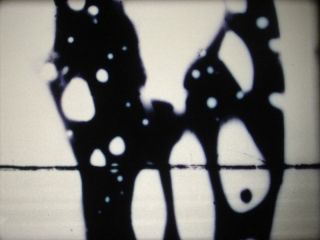

His first ‘electromedia event’ BLACK (1965) fused painting, music, poetry and dance with projected ‘lumigrams’ (hand-painted glass slides) in an immersive environment. The idea of ‘black’ as a spatial and psychological concept dominated Tambellini’s work for many years. “Black to me is like a beginning … Black is within totality, the oneness of all. Black is the expansion of consciousness in all directions.”

The Black Film Series, a sequence of seven films made between 1965-69, is a primitive, sensory exploration of the medium, which ranges from total abstraction to the assassination of Bobby Kennedy, the Vietnam War, and black teenagers in Coney Island. Before picking up a camera, Tambellini physically worked on the film strip, treating the emulsion with chemicals, paint, ink and stencils, slicing and scraping the celluloid, and dynamically intercutting material from industrial films, newsreels and broadcast television. Abrasive, provocative and turbulent, the series is a rapid-fire response to the beginning of the information age and a world in flux.

In 1966, Tambellini purchased the first Sony video recorder and made an experimental tape by shining a light directly into the camera lens, burning out the photoconductive vidicon tube. This monochrome tape was broadcast by ABC Television in 1967. Black Video Two – spontaneously improvised from test signals whilst the first tape was being duplicated – was later colourized using the Paik-Abe Video Synthesizer at WNET (1973) to create 6673.

One of the first artists to explore television as a means of personal expression, Tambellini collaborated with Otto Piene on Black Gate Cologne, an hour-long multi-media happening broadcast by WDR in January 1969, and contributed to The Medium is the Medium at WGBH Boston, alongside Nam June Paik and Allan Kaprow (also 1969). That same year, under commission from the Howard Wise Gallery, Tambellini worked with Bell Laboratories engineers to create Black Spiral, a manipulated television set, for the groundbreaking exhibition “TV as a Creative Medium”.

During his tenure at the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the 1970s and 1980s, Tambellini established Communicationsphere, connecting artists with technicians and engineers to “dissolve the boundaries between media, the arts and life.” Most recently he has returned to writing and performing poetry, and made the award-winning digital video poem Listen (2005) in collaboration with Anthony Tenczar.

Reaching beyond its application as an aesthetic tool, Tambellini has consistently used media as a means of social and political communication, often working in collaboration with others to investigate the creative potential of electronics and technology.

BLACK FILM SERIES

“Tambellini is one of the pioneers of lntermedia. His Black series in film and intermedia is obsessed with Black. His Black is like a ‘blind spot’ – a phantasy with the speed of nightmare. Hypnotic effect of organic microscopic forms. From darkness of the daemon to brightness to sperm to womb to friction contraction expansion. It is a trip for blind America.” Takahiko Iimura, Eiga Hyoron (Japanese Film Review)

BLACK IS

Aldo Tambellini, 1965, 16mm, b/w, sound, 4 min

seed black

seed black

sperm black

sperm black

a film made entirely without the use of the camera

(Aldo Tambellini)

BLACK TRIP #1

Aldo Tambellini, 1965, 16mm, b/w, sound, 5 min

Black Trip #1 is pure abstraction after the manner of a Jackson Pollock. Through the uses of kinescope, video, multimedia, and direct painting on film, an impression is gained of the frantic action of protoplasm under a microscope where an imaginative viewer may see the genesis of it all. (Grove Press Film Catalog)

BLACK TRIP #2

Aldo Tambellini, 1967, 16mm, b/w, sound, 3 min

“An internal probing of the violence and mystery of the American psyche seen through the eye of a black man and the Russian revolution.” (Aldo Tambellini)

BLACKOUT

Aldo Tambellini, 1965, 16mm, b/w, sound, 9 min

This film, like an action painting by Franz Kline, is a rising crescendo of abstract images. Rapid cuts of white forms on a black background supplemented by an equally abstract soundtrack give the impression of a bombardment in celestial space or on a battlefield where cannons fire on an unseen enemy into the night. (Grove Press Film Catalog)

BLACK PLUS X

Aldo Tambellini, 1966, 16mm, b/w, sound, 9 min

Tambellini here focuses on contemporary life in a black community. The extra, the “X” of Black Plus X, is a filmic device by which a black person is instantaneously turned white by the mere projection of the negative image. The time is summer, and the place is an oceanside amusement park where black children are playing in the surf and enjoying the rides, quite oblivious to Tambellini’s tongue?in?cheek “solution” to the race problem. (Grove Press Film Catalog)

BLACK TV

Aldo Tambellini, 1968, 16mm, b/w, sound, 10 min

The film is an artist’s sensory perception of the violence of the world we live in, projected through a television tube. Tambellini presents it subliminally in rapid?fire abstractions in which such horrors as Robert Kennedy’s assassination, murder, infanticide, prize fights, police brutality at Chicago, and the war in Vietnam are out?of?focus impressions of faces and events.” (Grove Press Film Catalog)

ABC-TV INTERVIEW

Aldo Tambellini, 1967, video, b/w, sound, 3 min

This interview with Aldo Tambellini was shot on 21st December 1967, at the Black Gate Theatre, for an ABC Television series on the New York Lower East Side Arts Scene. It includes an excerpt from Black Video One, his first experimental videotape, which had been made the previous year by shining a light directly into the camera lens, burning out the photoconductive vidicon tube.

BLACK (EXCERPT FROM THE MEDIUM IS THE MEDIUM)

Aldo Tambellini, 1969, video, b/w, sound, c.6 min

“In 1969 [Tambellini] was one of six artists participating in the PBL programme “The Medium Is the Medium” at WGBH-TV in Boston. The videotape produced for the project, called Black, involved one thousand slides, seven 16mm film projections, thirty black children, and three live TV cameras that taped the interplay of sound and image. The black-and-white tape is extremely dense in kinetic and synaesthetic information, assaulting the senses in a subliminal barrage of sight and sound events. The slides and films were projected on and around the children in the studio, creating an overwhelming sense of the black man’s life in contemporary America. Images from all three cameras were superimposed on one tape, resulting in a multidimensional presentation of an ethnological attitude. There was a strong sense of furious energy, both Tambellini’s and the blacks’, communicated through the space/time manipulations of the medium.” (Gene Youngbood, Expanded Cinema)

SCREENING ON A MONITOR IN THE FOYER

6673

Aldo Tambellini, 1966-73, video, colour, sound, 55 min (looped)

6673 is based on Tambellini’s second tape, Black Video 2, which dates from 1966. It was created at the Video Flight dubbing house by manipulating test patterns and other electronic signals. The soundtrack combines audio produced by an oscilloscope (which also distorted the images) with Tambellini’s wordless, vocal improvisation. In 1973, Tambellini added colour and further manipulated the original material using the Paik-Abe Synthesiser at WNET’s artists’ television lab in New York.

Back to top

Date: 25 October 2007 | Season: London Film Festival 2007 | Tags: London Film Festival

DAVID GATTEN: THE IMAGE & THE WORD (WORKSHOP)

Thursday 25 October 2007, from 10am-5pm

London BFI Southbank

Festival guest David Gatten leads a practical workshop on the use of text in 16mm filmmaking.

DAVID GATTEN: THE IMAGE & THE WORD (WORKSHOP)

Throughout the history of cinema, images and text have been combined on-screen in a variety of ways and for a range of reasons. Silent-era comedy, mid-century newsreels, avant-garde films and home movies have used words to tell stories, convey facts and explore the enjoyments and anxieties of reading. In this day-long workshop, Brooklyn artist David Gatten will provide an overview of such practice, with particular attention to filmmakers who have deployed on-screen text to investigate the way text functions as both image and language, the border between the legible and illegible, and the limits of what can be known through words.

David Gatten has made prominent use of the printed word in the ongoing series The Secret History of the Dividing Line (sections screened at the LFF in previous years) and his recent Film for Invisible Ink, Case No: 71: Base-Plus-Fog (showing in the Festival on 28 October 2007). Following introductory screenings of relevant works, participants will make their own films using a variety of processes, including direct-on-film applications, ink-and-cellophane tape transfers, slide projections, close-up cinematography, in-camera contact printing and more.

The workshop is suitable for both beginners and experienced practitioners.

Presented in association with no.w.here.

Back to top

Date: 27 October 2007 | Season: London Film Festival 2007 | Tags: London Film Festival

THE ‘I’ AND THE ‘WE’

Saturday 27 October 2007, at 2pm

London BFI Southbank NFT3

Su Friedrich, Seeing Red, USA, 2005, 27 min

A video confessional in which the artist expresses her frustration with the onset of middle age, frankly declaring personal anxieties. Interspersed with observational vignettes edited to Bach’s Goldberg Variations (played by Glenn Gould), Seeing Red is ultimately less an admission of crisis than a roar of defiance.

Elodie Pong, Je Suis Une Bombe, Switzerland, 2006, 7 min

Unprecedented and absolute: The image of a young woman ‘simultaneously strong and vulnerable, a potential powder keg.’

Jay Rosenblatt, I Just Wanted to Be Somebody, USA, 2006, 10 min

American pop singer Anita Bryant, the face of Florida orange juice, led a political crusade against the ‘evil forces’ of homosexuality in the 1970s. Local success was short lived, and a national boycott of Florida oranges was the first sign of her loss of public approval.

Steve Reinke, Regarding the Pain of Susan Sontag (Notes on Camp), Canada, 2006, 4 min

A journey from schoolyard to graveyard, with author Susan Sontag as philosophical guide.

Mara Mattuschka & Chris Haring, Part Time Heroes, Austria, 2007, 33 min

Mattuschka’s second adaptation of a piece by Vienna’s ingenious Liquid Loft (following Legal Errorist in 2004) exposes a trio of fractured characters. In the lonely hearts hotel of an unfamiliar zone, the amorphous heroes erratically construct and reveal their unconventional personas

PROGRAMME NOTES

THE ‘I’ AND THE ‘WE’

Saturday 27 October 2007, at 2pm

London BFI Southbank NFT3

SEEING RED

Su Friedrich, USA, 2005, video, colour, sound, 27 min

Su Friedrich created her latest experimental documentary, the half-hour Seeing Red, from just three elements: video diaries, shot from the chin down, in which she wears a red top; seemingly aleatory footage, often taken on the sly, of red things found on streets, in parks, or in backyards; and snatches of Glenn Gould’s rendition of Bach’s ‘Goldberg Variations’. At times, red bits of the world dance ecstatically to Gould’s cascading keys. Alone, to her camera, Friedrich confesses a string of related fears: Having turned 50, she faces the stubborn constancy of her self-identified ‘control freak’ patterns and insecurities and wonders if she still has time to change for the better. Friedrich is one of the most accomplished avant-garde filmmakers of her generation, with a career of films and videos whose masterful construction and precise beauty attest to the positive aspects of her self-criticism, and her stature only makes the humbling existential crises in Seeing Red more poignant. Yet she has always found ways to create beauty that resist the illusion of transcendence by sticking close to the grounds of hard reality – an influence and logical extension of her feminist politics. (Ed Halter, Village Voice)

www.sufriedrich.com

JE SUIS UNE BOMBE

Elodie Pong, Switzerland, 2006, video, colour, sound, 7 min

In her video Je suis une bombe, which is part of the ‘Supernova’ cycle, Elodie Pong presents a young woman wearing a panda bear costume who dances and writhes around a pole, in the manner of striptease performers. At the end of the performance, the young woman takes off her panda head and, holding it in her hand, moves towards the camera. Repeatedly and with a sense of urgency, she says ‘Je suis une bombe’, as if she needed to convince herself of her own peculiarity. In her videos Pong paints a kaleidoscopic picture of her own generation which she has pegged as narcissistic, searching, and performance-oriented. She remains a bit aloof, but never severs the ties with her protagonists – she knows, after all, that she herself is deeply involved. The body becomes the carrier of communication. This is not surprising as it is mainly the body which shapes our identity today. Pong tries to capture the reality of a generation by juxtaposing the subjective and the objective, as well as the real and the illusionary. The artist runs the entire gamut of contemporary emotions, and underneath some innocuous looking surfaces she discovers the depths of a silent world drowned out by ambient noise. (Kunsthaus Baselland)

I JUST WANTED TO BE SOMEBODY

Jay Rosenblatt, USA, 2006, video, colour, sound, 10 min

‘I believe, more than ever before, that there are evil forces round about us. Maybe even disguised as something good.’ These are the ironic words of the former beauty queen Anita Bryant, who became the face of homophobia in the United States in the 1970s. In I Just Wanted to Be Somebody, director Jay Rosenblatt sketches a portrait as funny as it is serious of the woman who unleashed the first public controversy over civil rights for homosexuals in 1977 by leading a successful local campaign against them. ‘In Florida, you won the battle, but lost the war. You gave a face to fear and ignorance’ was the response that Fenton Johnson, a gay American writer, wrote in a letter to her as an invitation to keep the debate alive. Rosenblatt creates comic effects by combining the public appearances in which Bryant warns against gay love with commercials that have her singing the praises of orange juice and vitamin C. But in no way does this make the danger of fear and ignorance any less recognisable. I Just Wanted to Be Somebody takes a stand for the importance of a discussion that Bryant is no longer willing to participate in. She lost her career and her family, but not her convictions. (International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam)

www.jayrosenblattfilms.com

REGARDING THE PAIN OF SUSAN SONTAG (NOTES ON CAMP)

Steve Reinke, Canada, 2006, video, colour, sound, 4 min

This short video gets its name from two pieces of writing by Susan Sontag: her last book, Regarding the Pain of Others, a meditation on empathy and the photograph as document; and the highly influential essay, now close to fifty years old, Notes on Camp. Sontag’s work often questions photography’s ability to elicit empathy within the viewer. She analyzes whether personal topics, such as gender and disease, can be addressed given the vast dissemination of photographic images. Outed in the invite as a rehabilitation of the ‘tired indexicality of photograph’, Regarding the Pain of Susan Sontag (Notes on Camp), shows images that evoke a contemporary emotional ground zero, combined with Reinke’s pithy voice-over narration. (LUX)

www.myrectumisnotagrave.com

PART TIME HEROES

Mara Mattuschka, Chris Haring, Austria, 2007, video, colour, sound, 33 min

The search for fame’s elevator goes up and down, the ego’s bust and boom. Each character is isolated in his or her anachronistic, film-star dressing room, left alone, subjected to the sinister fittings: a hopelessly out-dated microphone, radio, crutches for communication. Each character gets a small chance to show that he or she alone is better at embodying that self, which is just as good as every other self. However, as though it were an uncanny copy machine of star production, the golden room, which houses the greatest striptease talent – since she constantly undress yet is never naked – generates a momentary double. The film checks these beings, isolated through their hero competition, into the lonely heart hotel where they eavesdrop on one another through thin walls, often over a film cut. Frivolous encounters slip in. A helplessly obscene seduction attempt mutates to telephone terror, confirmed by the humorous play of the eyes from the other side. From out of the elevator, an elevator technician – a show master, so to speak, a running gag, a lascivious ‘cursor’ in a boiler suit – creeps down the hallways. He alone seems to connect everything, but finds no one. Until the final take, a generous long shot in which all three heroes are left to their own showcases, whereby they attempt all together, each alone, to seduce their audience. Yet unimpressed passers-by give our heroes the cold shoulder, making the camera on the other side of the street their only audience. The Oseifabrik, furnished with technology from days gone by, lends eccentric historicity to one of the programmatic statements: ‘How do I become timeless?’ that releases this outcry for fame in a hopeless but unique vitality. (Katherina Zakravsky)

Back to top

Date: 27 October 2007 | Season: London Film Festival 2007 | Tags: London Film Festival

MYSTERIOUS EMULSION

Saturday 27 October 2007, at 9pm

London BFI Southbank NFT3

Sandy Ding, Water Spell, USA, 2007, 42 min

A journey from realism to a supersensory realm, slipping under the surface and between molecules at a microscopic scale. Channeling the subconscious, Water Spell is both odyssey and invocation; a ritual of transformation and retinal blast. The film releases the energy locked within its frames through flickering pulsations of light.

Carl E. Brown, Blue Monet, Canada, 2006, 56 min (double screen)

Rarely shown in the UK, Carl Brown is a long-established film artist whose practice is dedicated to the modification of images by chemical means. Blue Monet is an homage to the French Impressionist, and an attempt to bring the Monet experience into the realm of cinema. Through the ebb and flow of intricate imagery, water lilies eternally blossom and fade with otherworldly grace. Brown has used his alchemical techniques to transfer Monet’s sense of colour, light, sky and water onto film. Viewed in spacious double-screen and enhanced by swathes of sound, this film is an immersive experience.

PROGRAMME NOTES

MYSTERIOUS EMULSION

Saturday 27 October 2007, at 9pm

London BFI Southbank NFT3

WATER SPELL

Sandy Ding, USA, 2007, 16mm, b/w & colour, sound, 42 min

Sandy Ding’s Water Spell is a bold, abstract journey that takes us into the psychic interior of our very cellular structure … and back. For me, this film is about reincarnation and transformation, on both the spiritual and sub-atomic levels. This is not an easy film, but it is a powerful one. (Nina Menkes)

BLUE MONET

Carl E. Brown, Canada, 2006, 2 x 16mm, colour, sound, 56 min (double screen)

This is an homage to Claude Monet and Eustace R. Brown who both taught me to ‘cultivate my garden’. In my film work over the past twenty years water has always been a touchstone for my emotional state. To look out at the water whether it be lake or sea is to face the two endless zones, that of water and sky and the mysterious edge at which they meet. I find this vision one of the strongest intimations of infinity. Monet is an artist that I have always greatly admired. His use of colour through water and sky to convey his emotional state has had a great influence on me. Whether it was the first rays of light glinting the water’s edge or the magic time just before nightfall, Monet’s sense of colour and colour conveyance has always been perfect. I have used my techniques of alchemical film to translate onto film my impressions of Monet’s sense of colour, water, sky and his most powerful icon the water lily. Using my toning, liquid emulsion, reticulation, dried crystal bleach formations and stacking techniques to just name a few I have translated the Monet experience onto the surface of my film. An illustrational form tells you through its intelligence immediately what the form is about, whereas a nonillustrational form works first upon sensation and then slowly leaks back into fact. Alchemical work provides both illustration and nonillustration simultaneously … the experiential depth of representation (the photographic source), and a sensuous (abstract) surface of the wild, both seen and unseen … but felt. That is what is art creation; a union between the beauty that is Monet converted through my alchemical nature into a new form for a new generation of viewers. (Carl E. Brown)

Back to top

Date: 27 October 2007 | Season: London Film Festival 2007 | Tags: London Film Festival

CAROLEE SCHNEEMANN PRESERVATIONS

Saturday 27 October 2007, at 7pm

London BFI Southbank NFT3

Newly preserved prints. Carolee Schneemann is a multi-media artist whose films, performances, installations and writings are a radical discourse on the body, sexuality and gender.

Carolee Schneemann, Fuses, USA, 1964-67, 29 min

Fuses is a vibrant celebration of a passionate relationship, openly portraying sexual intercourse without the objectification of pornography. To extend the tactile intimacy of lovemaking to filmmaking, Schneemann treated the filmstrips as a canvas, working by hand to paint, transform and cut the footage into a dense collage. The erotic energy of the body is transferred directly onto the film material. Recently preserved by Anthology Film Archives, this legendary work glows with a clarity unseen since its debut in the 1960s.

Carolee Schneemann, Kitch’s Last Meal, USA, 1973-76, c.60 min

The moving conclusion to the autobiographical trilogy which began with Fuses, Kitch’s Last Meal documents the routines of daily life. It was shot on the Super-8 home movie format and is projected double screen (one image above the other) as an interchangeable set of 18-minute reels. The soundtrack mixes personal reminiscences with ambient sounds of the household, and includes the original text used for Schneemann’s 1975 performance ‘Interior Scroll’. Time passes, a relationship winds down and death closes in: filming and recording stopped when the elderly cat Kitch, Schneemann’s closest companion for two decades, died. Each performance of the film in its original state was a re-ordering of the visual and aural materials, arranged by the artist according to mood and environment. For the preservation print, three pairs of reels have been selected and blown up to 16mm.

PROGRAMME NOTES

CAROLEE SCHNEEMANN PRESERVATIONS

Saturday 27 October 2007, at 7pm

London BFI Southbank NFT3

FUSES

Carolee Schneemann, USA, 1964-67, 16mm, colour, sound, 29 min

I wanted to see if the experience of what I saw would have any correspondence to what I felt – the intimacy of the lovemaking … And I wanted to put into that materiality of film the energies of the body, so that the film itself dissolves and recombines and is transparent and dense – as one feels during lovemaking … It is different from any pornographic work that you’ve ever seen – that’s why people are still looking at it! And there’s no objectification or fetishization of the woman. (Carolee Schneemann)

By interweaving and compounding images of sexual love with images of mundane joy (the sea, a cat, window-filtered light), she expresses sex without the self consciousness of a spectacle, without an idea of expressivity, in her words, ‘free in a process which liberates our intentions from our conceptions’. Carolee and her lover James Tenney emerge from nebulous clusters of colour and light and are seen in every manner of sexual embrace … one overall mosaic of flesh and textures and passionate embraces. Every element of the traditional stag film is here – fellatio, cunnilingus, close-ups of genitals and penetrations, sexual acrobatics – yet there’s none of the prurience and dispassion usually associated with them. There is only a fluid oceanic quality that merges the physical act with the metaphysical connotations, very Joycean and very erotic. (Gene Youngblood, Expanded Cinema)

Pornography is an anti-emotional medium, in content and intent, and its lack of emotion renders it wholly ineffective for women. This absence of sensuality is so contrary to female eroticism that pornography becomes, in fact, anti-sexual. Schneemann’s film, by contrast, is devastatingly erotic, transcending the surfaces of sex to communicate its true spirit, its meaning as an activity for herself and, quite accurately, women in general. Significantly, Schneemann conceives the film as shot through the eyes of her cat – the impassive observer whose view of human sexuality is free of voyeurism and ignorant of morality. In her attempt to reproduce the whole visual and tactile experience of lovemaking as a subjective phenomenon Schneemann spent some three years marking on the film, baking it in the oven, even hanging it out the window during rainstorms on the off chance it might be struck by lightning. Much as human beings carry the physical traces of their experiences, so this film testifies to what it has been through and communicates the spirit of its maker. The red heat baked into the emulsion suffuses the film, a concrete emblem of erotic power.’ (B. Ruby Rich, Chicago Art Institute)

The preservation of Fuses by Anthology Film Archives, New York, was supported by the University of Chicago Film Studies Center and the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

KITCH’S LAST MEAL

Carolee Schneemann, USA, 1973-76, 2 x 16mm, colour, sound-on-cd, 3 x 20 min

In Kitch’s Last Meal synchronicity becomes a physical property, as with accident, as with joke – double entendre. The actual projection system is of two simultaneous Super 8 reels – vertical, one above the other. The disjunctive imagery has been intricately edited: two reels periodically phrase simultaneous images of the local freight train, which ran behind our house, as well as domestic events between the artist couple and the thematic constancy of the cat, Kitch, eating during the last four years of her life.

The film is composed of five hours of double co-ordinated reels; each set approximately twenty minutes long, so that various time units can be shown. The reels were edited over the five years of the filming. The sound was edited on cassette tapes.

The double vertical projection was intended to increase perceptual tension and its incremental satisfactions during the unexpected synchronisation of the horizontal entrance and exit of the train, of the figures moving in space, of the cat leaning to her dish. The verticality emphasises the axis of the body – its aspect of elongation in contrast to more predictable bilateral symmetry, the horizontal nature of stereoscopic vision. The repeated motions of the freight train situates a narrative physicalisation, corresponding with film itself moving through the mechanisation of the fixed track. Here the edge of the frame implies a leakage of time existing both before and after, just as the train enters our perceptual field seemingly from elsewhere (behind, moving forward to an invisible destination). At the conclusion of reels 11 & 12, I stand in the railroad tracks filming a train in diminishing perspective – as if time is actually being pulled away, as if the scale of an object can be reduced to a grain, a blur.

The visual parameters were determined by placing the camera close to positions occupied by the cat. The sound was recorded by suspending a microphone adjacent to the cat both indoors and outdoors. My premise was to film fragments of Kitch’s observations so long as she lived. I began this diary film on returning home to the Hudson Valley with the cat after dislocated years in Europe. Kitch, returning to her original house was already 16 years old. Since death and film seemed in a determined interchange, my intention was to film the cat in our domestic surround until she died.

Stan Brakhage always told me how mysteriously and consistently places he filmed were subsequently destroyed – houses disappeared, bridges were taken down; friends appearing in his films would soon move away, often without a trace. With Fuses, the celebration of an equitable and passionate relationship unexpectedly dissolved; Plumb Line became the imprints of a deforming love affair; Viet-Flakes observed fragments of brutality and disaster; while my small film portrait Carl Ruggles Christmas Breakfast captured the composer at 84 years old – the unintended poignancy of a simple meal. By 1973, the premise of Kitch’s Last Meal seemed to provide certain safety valves.

Our collusion was such that Kitch died almost 20 years old while eating a lamp chop. Kitch died on February 3rd. In March, the Walkill Valley Railroad announced that the small freight running behind the house from Albany to Walkill would be discontinued and the tracks dismantled. In May, my partner Anthony McCall decided we should separate and in June I was informed my teaching position would not be renewed. So much for my anticipated trade-off with film-death!

(Carolee Schneemann)

The 16mm blow-up and preservation of Kitch’s Last Meal by Anthology Film Archives, New York, was supported by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

Back to top