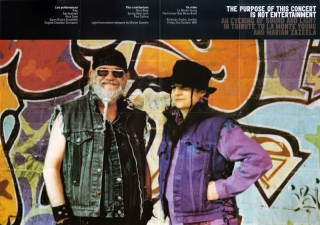

THE PURPOSE OF THIS CONCERT IS NOT ENTERTAINMENT

Friday 31 October 1997

London Barbican Centre

La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela

La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela have spent every night of their lives together since the day they officially got together: June 22, 1962. And except for a brief period in the early eighties, when they had a second living space a few blocks away, they have lived in the same downtown loft on Church Street in New York City since 1963, regularly sharing it, since the early seventies, with their former teacher, north Indian classical singer Pandit Pran Nath, who passed away earlier this year. In his typically colourful way, Young recently described their life together as “two turtles, living in a dream house.”

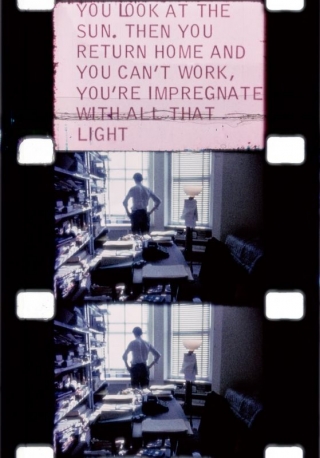

If it sounds as if things move slowly in their lives, the same is doubly true in their art. Even when playing microtonal blues, Young can take hours to get to the next chord change. And Zazeela’s light shows, normally in a magenta hue, appear not to move at all, except for the shadows, which are never the same. When I told the composer Ben Johnston I planned to interview La Monte and Marian, he said, “You’d do well to remember that they function as close to a single entity as any two people you’re ever likely to meet.” Certainly, in conversation, they do talk at the same time, always completing each other’s sentences. But the most compelling thing about their relationship, to my mind, is how slowly things move in their presence. This is true even in sleep, where they are on a twenty-seven-hour cycle that, depending on the day, can have them awake or asleep at any hour of the day or night.

Born a Mormon, in a log cabin, in a town of 149 people in Idaho, La Monte Young remembers the vast sense of time and distance he felt as a child. He also remembers the wind blowing through the logs of the cabin, the sound of insects, and the slow-moving clouds, all of which would later have an effect on his music. When he was three, his aunt, who sang at rodeos, taught him to play guitar. When he was seven, his father, a sheepherder, taught him saxophone, beating him when he played wrong notes. Young says he didn’t hear any classical music until sometime in high school, after his family had moved permanently to Los Angeles. As he recalls, his “first big taste of modern music” was the Bartok Concerto for Orchestra, heard on a class trip to the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

In high school, Young practiced a series of long-tone exercises on saxophone that he eventually came to regard as the beginning of his interest in sound vibrations “on a higher level.” He identifies the summer of 1957, when he was in his early twenties, as a turning point, saying he spent the entire summer on a bed in his grandmother’s house in L.A., meditating and listening to sounds. Young describes this time as the only point in his life where he ever questioned his direction in music. Later, he said his work with long tones was what led him to work with tunings, since a sustained tone allows the harmonics to be heard, which quickly leads to the area of just intonation.

In 1953, Young began classes at L.A. City College, beating out Eric Dolphy for a chair in the dance band. During the mid-fifties, jazz and experimental music coexisted in his mind, but by the time of his arrival at Berkeley in 1958 to begin a graduate degree, he had devoted himself to composition. At Berkeley, Young studied with Seymour Shifrin, in a class that included both Pauline Oliveros and Terry Riley. His most important work from this period is his Trio for Strings, an hour-long, serial piece from 1958 that is built entirely of long tones and silences. It is probably this work, more than any other, that solidifies Young’s reputation as the “Godfather of Minimalism.”

In 1959, Young attended the summer course in new music at Darmstadt, Germany. He went to study with Stockhausen, but came away highly influenced by the music and philosophy of John Cage and the piano recitals given by David Tudor. The next year, showing the influences of both Cage and Japanese haiku, Young wrote his radically different Compositions 1960, a group of poetry-like prose instructions, one of which directs the performer to “Draw a straight line and follow it.” Also in 1960, Young moved to New York to study electronic music with Richard Maxfield, and by the end of the year, had organized what may have been the first loft concert series in New York at Yoko Ono’s loft on Chambers Street.

Marian Zazeela grew up in a completely different world. Born in New York, she majored in art at the High School of Music and Art, before going to Bennington College in Vermont to major in painting, studying with Paul Feeley, Eugene Goossens, and Tony Smith, among others. Her first New York exhibition, a two-artist show at the 92nd Street YM-YWHA in 1960, was awarded to her by the art department of the college. Her large canvases of this period, with names like Blue Train and Woodcut 1960, are composed of freely drawn calligraphic strokes suspended in static, contrasting colour fields, and show the influence of two trips to Tangiers. Zazeela now says she thinks of these works as seeds, leading directly to her two major lightworks: Ornamental Lightyears Tracery, an ongoing series of short-term performances throughout the seventies, and The Magenta Lights, the environment designed specifically for performances of Young’s The Well-Tuned Piano.

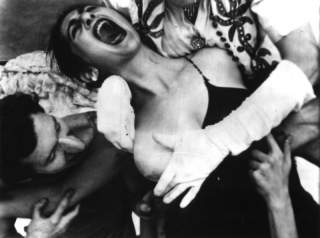

In New York after college, Zazeela first moved among a circle of writers, once designing a stage set for Amiri Baraka (who was then known as LeRoi Jones). During the early sixties, she was also a super-model for Jack Smith, appearing not only as the primary subject for his legendary book of nude photographs, The Beautiful Book, but also in the featured still cameo of his banned movie, Flaming Creatures (along with Young, who, because of her, had a minor role). She would have been the main character of the movie – the part was written for her – but she had recently met Young and found his world suddenly consuming all of hers.

At first, Zazeela’s work with Young consisted of performing drone parts as a member of his group, The Theatre of Eternal Music, which at one time included John Cale, Tony Conrad, and Angus MacLise. Terry Riley, Billy Name, Jon Hassel and Jon Gibson have also participated in this group at various times. But in 1964, Zazeela also began creating a visual presentation as well, first with light boxes glowing with calligraphic patterns, later, with photographs of these patterns projected onto the performers. By 1965, her calligraphic light projections were incorporating, as she says, the elements of time into the work. And by 1968, these lightworks had become environments, creating what she called “three-dimensional coloured shadows.” Since the 1960’s Zazeela and Young have moved slowly away from the idea of concert-hall performances, creating instead, these environments in which Young’s five- and six-hour pieces gradually unfold, bathed in lights Zazeela once described as the “soft reflected light of dusk, suspended in time.”

Although Young and Zazeela have worked together on a number of projects, their two most significant, continuing collaborations are The Well-Tuned Piano and Dream House. The Well-Tuned Piano, currently approaching seven hours in length, is a work for justly tuned piano, begun by Young in 1964, in which events unfold at a glacial pace, with chords and intervals of the microtonal scale appearing slowly, in a prescribed order, over a span of hours. It is also a piece in which new material is developed each time it is played, which is why it gets longer with each performance. Beginning with the 1974 premiere in Rome, Zazeela’s lightwork The Magenta Lights has always been the environment in which Young performs The Well-Tuned Piano. He says he will never perform it any other way.

Dream House, on the other hand, is a much longer sound and light environment designed to exist over a period of weeks, months, or even years. Originally begun as a harmonically complex set of drones in their loft in the early sixties, Dream House evolved, first, into a series of short-term performances / installations in which Young’s Map of 49’s Dream The Two Systems of Eleven Sets of Galactic Intervals Ornamental Lightyears Tracery was performed, then, into a permanent installation on Harrison Street in New York, supported by the Dia Art Foundation. Unfortunately, after running for six years, economic problems within the foundation forced its closing in 1985. There is currently a seven year long Dream House installed on the floor above Young and Zazeela’s Church Street loft.

In 1990, Zazeela’s exhibition of lightworks at the Donguy Gallery in Paris was purchased by the French cultural ministry for permanent installation in France. That same year, Young formed the Forever Bad Blues Band, consisting of microtonal keyboard, guitar, and bass guitar, plus drums. Two years later, the band toured Europe, performing a two-hour version of Young’s Dorian Blues in just intonation, in a light and shadow environment created by Zazeela.

Written by William Duckworth. Reprinted by kind permission.

The original version of this article first appeared as the introduction to an interview with La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela in the book “Talking Music” by William Duckworth, published by Schirmer Books.

Inventing America

“Inventing America” is a year long celebration of American culture to be hosted by the Barbican Centre throughout 1998. The month of October will be dedicated to new music and minimalism. It will feature the first ever UK performance of La Monte Young’s Theatre Of Eternal Music. Other events will include the music of John Cage, Philip Glass, John Adams, Newband playing the original Harry Partch instruments, and a special concert featuring Pulp and Terry Riley. Call 0171 382 7101 to receive further information as events are confirmed.

La Monte Young Marian Zazeela Benefit Concert

When I first heard that Marian was ill and I had the idea of a fundraising concert, I had no idea that we would put together such a fantastic event. I gratefully acknowledge the amount of work that has gone into making this evening possible, and I hope that this event will raise awareness of the scope and brilliance of the work of La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela. Thank you to everyone involved. (Mark Webber)

This concert would not have been possible without the generous contributions of the following people :

Pulp, J Spaceman, Nick Cave and Warren Ellis, Gavin Bryars Ensemble, Monaco String Quartet, Steve Martland, Spring Heel Jack, Terry Riley, Yoko Ono, Paul Catling, Charles Hazlewood, Anthony H Wilson, Alex Poots and the Barbican Centre.

Additional PA and lighting has been provided by Juice Sound and Light.

We would also like to thank…

Robert, Charlotte, Ruth, David and all at the Barbican who helped with this event, especially Technical Services and all at the Box Office. Geoff, Jeanette, Pru, Patsy, Glen and Kelly at Rough Trade Management. John and Melissa at Savage & Best. Scott, Nicky and Vicky at Appearing. Jeff Craft at Fair Warning/ICM. Eddie Grossman at Martin Greene Ravden. Ed Baxter and all at the London Musicians Collective. Simon Long at The Simkins Partnership. Robert Warby, Georgina Langdale. Sally Groves at Schott.

Thanks also to the ECO, Jane Quinn, Tara-Jane Zagacki, Rayner Jesson, Jutta & Carsten Brandt, Mike Scoble, Roger Middlecoate, Simon Dawson, David Toop, Tony Robinson, Rob Charles, Kevin Brown, Don Owen, Ray Moonshake, Tim Lewis, Mike Kearsey, Anthony Genn, Martin Green, Macari’s Musical Instruments and Colorsound Pedals, Freud Communications, Absolut, Pepsi-Cola, Holsten Pils, Xfm, Top Guard, Pablo and 333 Old Street.

Programme compiled by Mark Webber, designed by Blue Source and printed thanks to a contribution from Island Records.

Poster photograph of La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela at the performance of Poem for Chairs, Tables, Benches etc. at Concert I-Punkt Skateland, Hamburg. © Jutta Brandt, 1996.

Back to top