Date: 3 November 2000 | Season: Ken Jacobs Nervous System, London Film Festival 2000 | Tags: London Film Festival

KEN JACOBS’ NERVOUS SYSTEM: 1

44th Regus London Film Festival

Friday 3 November 2000, at 7:30pm

INSTRUCTIONS TO AUDIENCE

In order to appreciate the added depth of the Pulfrich 3D effect, the viewer should use the “Eye Opener” filter during both of the works presented in this programme. Please return the filter to cinema staff after the performance.

OPENING THE NINETEENTH CENTURY: 1896

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1990, Pulfrich 3D 16mm, colour, sound, 11 min

Shafting the screen: the projector beam maintains its angle as it meets the screen and keeps on going, introducing volume as well as light, just as in Paris, Cairo and Venice of a century ago happen to pass. Passing through the tunnel mid-film, a red flash will signal you to switch your single Pulfrich filter before your right eye to before your left (keep both eyes open). Centre seating is best: depth deepens viewing further from the screen. Handle filter by edges to preserve clarity. Either side of filter may face screen. Filter can be held at any angle, there’s no “up” or “down” side. Also, two filters before an eye does not work better than one, and a filter in front of each only negates the effects. (Ken Jacobs)

BITEMPORAL VISION: THE SEA

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1994, Pulfrich 3D Nervous System, b/w, sound, c.70 min

Nervous System riff on 587 frames photographed by filmmaker Phil Solomon. This work was inspired, during a visit to Hamburg, by the photography of Daniel Maier-Reimer. The surface of water becomes a hugely 3D cosmic cataclysm; what’s up, what’s down, forward or back or solid or open becomes entirely unstable. The mind is soon at sea, Rorschaching like crazy in the effort to maintain equilibrium. (Ken Jacobs)

Suggestions for use of the neutral density (Pulfrich) filter for Bitemporal Vision: The Sea :-

Only one filter to each viewer. Filter is held before one eye, both eyes remaining open. Viewer decides when to view the film through the filter, and which eye to place it in front of. Middle viewing positions are best (as with all stereo).

It takes time to appreciate the changes, and to familiarise with the process. Sail through any initial discomforts; the brain is a muscle that can be sluggish and grumpy when asked to learn new tricks.

The image is strongly 3D even without the filter but the filter will strongly enhance the depth. It can also radically change arrangement in depth. Choice of eye determines which parts of the scene are in front of or in back of other parts, and in which direction movement flows. The more abstract and non-representational the scene – releasing the mind from its knowledge of physical law and its expectations re. behaviour of objects in space – the more it is that changes can be seen; that is, acknowledged by the mind. So I suggest using the filter most intensively when this depiction of water is least recognisable as water. (Two straightforward camera takes are the basis of Bitemporal Vision: The Sea, but departure from the familiar will be unmistakable.) Try it, for instance, when the overall scene becomes lighter in tone following the first advancing wave. (A wave rumbling forward slightly below eye level…that will transform to a massive cloud form moving overhead …)

It may take a minute to adapt to the filter before seeing its effect. Hang in with it and more visual events will become apparent, all the drama and struggle and comings and goings of the details. Placing the filter left or right, to match the direction to which a form is moving, will advance that form towards the viewer. The filter can also convert a solid form into an open space, and (switch filter) vice-versa.

(Ken Jacobs)

FURTHER NOTES

THE PULFRICH EFFECT

The Pulfrich Effect. A dark grey filter is held before one eye, both eyes remaining open. The effect of the filter is a delay in the time it takes for the light that does pass through it to be signalled to the brain. One eye will now be seeing the image presently lighting up the screen while the other will be seeing the film frame flashed a moment ago. It becomes possible to offer the mind, simultaneously, two distinct but related views of a scene. Complete stereopsis becomes possible, convincing 3D, true-to-life or anything but according to how the two information bundles relate.

Each viewer of Bitemporal Vision: The Sea is offered a wand with truly magical properties. A filter on one end, it can be handled like a lorgnette. At the viewer’s discretion it can be placed when wanted either in front of the left or right eye, either enhancing the depth character of the scene or – especially in the more abstract passages – entirely transforming depth character. Shapes suddenly appear or disappear, or radically reshape. Figure and ground trade places; direction of movement changes.

But the viewer, of course, is not being asked to simply make note of the changes: They’re to be experienced, through intense and prolonged and empathetic observation.

The Nervous System consists, very basically, of two near identical prints on two stills capable of single frame advance and “freeze” (turning the movie back into a series of stills), frame … by … frame, in various degrees of synchronisation. Most often there’s only a single frame difference. Difference makes for movement and uncanny three dimensional space illusions via a shutting mask or spinning propeller up front, between the projectors, alternating the cast images. Tiny shifts in the way the two images overlap create radically different effects. The throbbing flickering is necessary to create “eternalisms”: unfrozen slices of time, sustained movements going nowhere unlike anything in life (at no time are loops employed).

I’ve said, “Advanced filmmaking leads to Muybridge”. That’s certainly true for me. Closing in on (to allow the expansion of) ever smaller pieces of time is my personal ever promising and inviting Black Hole. Actors’ faces can stun me with boredom. (Movies are about actors.) I confess I feel walled in by human faces altogether, not as misanthropic reaction but because the human colonisation of human experience, in our urban lives, is so thorough. It is astonishing to find oneself here with so many others to chat with, but isn’t this essentially a search party … with our work cut out for us? We’ve gotten caught in the makings of our own minds and the only way out seems to be to enter into the workings of the mind. Film – as itself the subject of inquiry – is the spell we enter so as to pull apart the fibres of this phantasm, our opportunity to lay out the mind in strips. So, if picking at the texture of cinema, at the end of its filmic phase, seems about as inward as one can get, it’s because the name of this digging tool I’ve devised, The Nervous System, also designates a main territory of its search, that place where we’ve blithely applied mechanism to mind, willy nilly producing that development of mind known as cinema. After all, the micro and macro worlds are equally “out there”. Fresh air rushes in from the core of things, too.

(Ken Jacobs)

Back to top

Date: 4 November 2000 | Season: Ken Jacobs Nervous System, London Film Festival 2000 | Tags: London Film Festival

KEN JACOBS’ NERVOUS SYSTEM: 2

44th Regus London Film Festival

Saturday 4 November 2000, at 1pm

THE GEORGETOWN LOOP

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1996, 35mm, b/w, silent, 11 min

Originally photographed in 1903, US Library of Congress collection. New arrangement in 1996 by Ken Jacobs, assisted by Florence Jacobs. 35mm optical rephotography by Sam Bush, Western Cine, Denver.

I’ve been raiding the Paper Print Collection of the Library Of Congress in Washington, DC, since the late 1960s with Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son. It’s a preserve of early cinema. Until 1912, in order to copyright film, one deposited with the library a positive from the negative printed on paper, unprojectable, but – unlike nitrate prints – capable of weathering the years without Crumbling into chemical volatility. And there the stacks rested, safely out of mind, hundreds and hundreds of silent rolls most less than 30 meters, many Edisons, American Mutoscope And Biograph, Gaumont, Lubin, Vitagraph …; cine-snatches of life as it was lived, vaudevillians, proto-dramas, and too many state parades. Until they were ripe for rediscovery and reevaluation, and rephotography back onto film. The Georgetown Loop is my 11-minute riff on “The Scenic Wonder of Colorado”, a rail-line built in the 1870s through daunting mountain terrain to serve the silver mining industry. I’ve called it the first landscape film deserving of an X-rating, and that it is, yet its secret subtitle is – I must whisper – (Celestial Railway). (Ken Jacobs)

“Elegantly reworking some 1906 footage of a train trip through the Colorado Rockies, the dean of radical filmmaking printed the original image and its mirror side by side to produce a stunning widescreen kaleidoscope effect. Did it really take 100 years of cinema for someone to execute this almost ridiculously simple idea ? “This landscape film deserves an X-rating”, says Jacobs.” (Jim Hoberman, Village Voice, 1996)

ONTIC ANTICS STARRING LAUREL AND HARDY

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1998, Nervous System, b/w, sound, c.60 min

“With his Nervous System film performances, Jacobs wrings changes out of startled frames and makes the infinitesimal matter. Ontic Antics with Laurel and Hardy – the simple shift of a vowel or the advance of a film frame creates a world of definition and character. Basking in that shade of difference he plumbs the frame with surgical decisiveness and amatory delicacy. Welcome to microtonal cinema. Taking Laurel and Hardy’s Berth Marks as point of departure, Jacobs supersedes slapstick, moving into the deeper dimensions of the human comedy. Psychological imbroglios, time-space predicaments, the unruliness of uncooperative gravity, the unlimited expressiveness of the limited body hallucinated into Rorschach-ing deliveries.” (Mark McElhatten)

Hardy walked a thin line between playing heavy and playing fatty. Laurel adopted a retarded squint, with suggestions of idiot savant. Their characters were at sea, clinging to each other as industrial capitalism was breaking up and sinking. Beautiful losers, they kept it funny, buoying our spirits. Laurel and Hardy … forever. (Ken Jacobs)

BERTH MARKS

Lewis R. Foster, USA, 1929, 16mm, b/w, sound, 18 min

Oliver Hardy goes to meet his partner Stan Laurel at the train station. They have a vaudeville act, which involves a bass fiddle, and are on their way to their next performance. They just barely make the train and are led to their berth, wreaking havoc amongst the other passengers in their wake. With much difficulty, they undress in their berth. As soon as they’re ready for bed, they arrive at Pottsville, their destination, and have to hurry off. Once the train has left the station, they discover that they have left their bass fiddle on board. But the situations aren’t important, it’s what the boys do with them – the way Ollie wanders around the station in search of Stan, just missing him several times, and the various contortions the pair try to get into their upper berth – that give the film its fun. Especially nice is the interchange between the boys and the conductor. When Ollie describes himself and Stan to the trainman as a “big-time vaudeville act”, the old man dryly replies, “Well, I bet you’re good !” (Janiss Garza, All Movie Guide)

DISORIENT EXPRESS

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1996, 35mm film, b/w, silent, 30 min

1906 – Original cinematographer unknown. 1996 – New arrangement by Ken Jacobs. Shots shown as found in “A Trip Down Mount Tamalpais”, the Paper Print Collection, Library of Congress. Optically copied by Sam Bush, Western Cine Lab., Denver, from l6mm to 35mm letterbox format to allow double-image mirroring in 1:85 ratio projection.

The same string of shots, in their entirety, is repeated in various placement and directional permutations. But this film is not a lately arrived example of ‘‘Structural Cinema”, where methods of ordering film materials often came to take on paramount value. (The viewer at some point grasped the method and that could be pretty much it.) I’m for order only to the extent it provides possibilities of fresh experience. For instance, kaleidoscopic symmetry in Disorient Express is not an end in itself. The radiant patterning that affirms the screen plane serves also to provide visual events of an entirely other magnitude. Flat transmutes repeatedly to massive depth illusion; yet that which appears so forcefully, convincingly in depth is patently unreal – an irrational space. The obvious filmic flips and turns (method is always evident) of the scenic trip provide perceptual challenges to our understanding of reality, and we are often unable to see things as we know they are.

With light-source shifted from heaven-sent to infernal, we see a landscape that could never be, except via cinema. A very early recording of a train trip through mountainous terrain, enthusiasm of the adventurous passengers on boisterous display, lends itself to us for a ride into each our own Rorschach wilderness. This careening trip also demands some hanging on, some output of viewer energy. The rightness of the closure (as I see it) was made possible by copying the film, for the last pass, in reverse motion.

Disorient Express takes you someplace else. A spin lasting 30 minutes, you really need to tap into your own reserves of energy. Hang on, please, this is not formalist cinema; order interests me only to the extent that it can provide experience. Watch the flat screen give way to some kind of 3D thrust, look for impossible depth inversions, for jewelled splendour, for CATscans of the brain. I’m banking on this film reviving a yen for expanded consciousness. (Ken Jacobs)

FURTHER NOTES

NOTES ON THE NERVOUS SYSTEM

The Nervous System consists, very basically, of two identical prints on two projectors capable of single-frame advance and “freeze” (turning the movie back into a series of closely related slides.) The twin prints plod through the projectors, frame … by … frame, in various degrees of synchronisation. Most often there’s only a single frame difference. Difference makes for movement, and uncanny three-dimensional space illusions via a shuttling mask or spinning propeller up front, between the projectors, alternating the cast images. Tiny shifts in the way the two images overlap create radically different effects. The throbbing flickering (which takes some getting used to, then becoming no more difficult than following a sunset through passing trees from a moving car) is necessary to create “eternalisms” – unfrozen slices of time, sustained movements going nowhere unlike anything in life (at no time are loops employed). For instance, without discernible start and stop and repeat points a neck may turn … eternally.

The aim is neither to achieve a life-like nor a Black Lagoon 3D illusionism, but to pull a tense plastic play of volume configurations and movements out of standard (2D) pictorial patterning. The space I mean to contract, however, is between now and then, that other present that dropped its shadow on film.

I enjoy mining existing film, seeing what film remembers, what’s missed when it clacks by at Normal Speed. Normal Speed is good ! It tells us stories and much more but it is inefficient in gleaning all possible information from the film-ribbon. And there’s already so much film. Let’s draw some of it out for a deep look, sometimes mix with it, take it further or at least into a new light with flexible expressive projection. We’re urban creatures, sadly, living in movies, i.e. forceful transmissions of other people’s ideas. To film our environment is to film film; it’s also a desperate approach to learning our own minds.

What I’m trying to do is shape a poetry of motion, time / motion studies touched and shifted with a concern for how things feel, to open fresh territory for sentient exploration, creating spectacle from dross … delving and learning beyond the intended message or cover-up, seeing how much history can be salvaged when film is wrested from glib 24 f.p.s. To tell a story in new ways, relating new energy components (words are energy components to a poet) in a system of construction natural to their particularity. To memorialise. To warn.

(Ken Jacobs)

Back to top

Date: 4 November 2000 | Season: London Film Festival 2000 | Tags: London Film Festival

AS I WAS MOVING AHEAD OCCASIONALLY I SAW BRIEF GLIMPSES OF BEAUTY

Saturday 4 November 2000, at 5pm

London National Film Theatre NFT2

As I Was Moving Ahead … is the new film from Jonas Mekas, the self-assumed saint of all cinema. This latest instalment of his diaries, covering the years 1970-99, continues in the style he originated in Walden (Diaries, Notes and Sketches) (1964-69). In these films, he has presented all aspects of his life, since the first shaky shots made in 1949, when he purchased a 16mm camera only weeks after arriving in New York, having spent four years in displaced persons camps across war torn Europe.

Mekas has been an untiring advocate of the art of film since co-founding Film Culture magazine in 1955, and from 1958-75 he wrote the influential Movie Journal column in the Village Voice newspaper. In the 1960s he was instigator of the Film-Makers’ Cooperative, a non-discriminatory distribution centre for experimental film. After presenting many showcases for experimental work, in 1970 Mekas realised his dream to build the “cathedral of cinema”, Anthology Film Archives, one of the earliest centres exclusively devoted to the preservation and presentation of Film As Art. At the age of 78, Mekas is still active as the artistic director Anthology and continues to be one of the driving forces of truly independent cinema.

In his films, Mekas tries to liberate cinema from convention; he is filming, but not making films. Months, seasons, years, come and go, and Jonas continues to record his life with a wide-eyed innocence. He impulsively documents what is happening around him by quickly shooting “fragments of time”, in which only quick bursts of several frames at a time may be exposed. Whether in the presence of fellow filmmakers, writers or musicians, or when spending time at home with his family, each is given the same attention from his camera gaze. Memories of his wedding, the birth and infancy of his son and daughter, trips to Europe and family holidays in New Hampshire are all here for us to share. A few well-know faces such as William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg or Elvis Presley may briefly appear, but it is not necessary to recognise anyone in the film, we can still each share the collective memories that relate to our own lives. These pages of his diary are less star-studded than previous films, it is an intensely personal work.

Sometimes Mekas comments on the action or occasionally philosophises, usually introducing each chapter by downplaying the significance of the footage, constantly reminding us that nothing happens in the film. That nothing happens is precisely what makes the film so wonderful. That which Mekas presents as the “ecstasy of being in New York” can be seen as the ecstasy of being alive. Life goes on, and Mekas, well known as a lover of cinema, is revealed to be a lover of humanity.

AS I WAS MOVING AHEAD OCCASIONALLY I SAW BRIEF GLIMPSES OF BEAUTY

Jonas Mekas, USA, 1970-99, 16mm, colour, sound, 320 min

Part 1, Chapters 1-6: Saturday 4 November 2000, at 5pm, NFT1

Part 2, Chapters 7-12: Sunday 5 November 2000, at 1pm, NFT2

Back to top

Date: 8 November 2001 | Season: London Film Festival 2001 | Tags: London Film Festival, Peter Kubelka, What is Film?

PETER KUBELKA: WHAT IS FILM?

8-14 November 2001

London National Film Theatre

“Peter Kubelka is the perfectionist of the film medium” (Stan Brakhage)

A series of four public lectures in which films from Lumière to the present day will be used to celebrate cinema as a cultural phenomenon, whilst defining film as an independent medium and distinguishing it from those arts that existed before it, and the new media (such as television and the internet) that have become dominant in recent years.

Peter Kubelka will demonstrate the unique and indispensable qualities of film through detailed analysis of those works that best represent the essence of the cinema. In this extraordinary series of events, he will expose the mechanics and grammar of film that are otherwise hidden from the public. After viewing the films, the audience will have an opportunity to look over his shoulder in a situation similar to that of seeing the filmmaker at the editing table. Using a projecting Steenbeck, Kubelka will analyse, letter by letter, the language that cinema speaks. He will argue that as each mode of communication induces its own world-view, the vital and autonomous experience of cinema cannot be transferred to other media without loss of content or the understanding of the artist’s original intentions. Film is a tool that is able to create new thoughts and Peter Kubelka will bring forth the hardcore of cinema: those ideas and concepts that cannot be touched by any other art form.

“Kubelka’s cinema is like a piece of crystal, or some other object of nature: it does not look like it was produced by man.” (P. Adams Sitney)

Peter Kubelka is one of the most distinguished figures in the history of 20th century independent filmmaking. His films, made between 1955 and 1977, are an innovative demonstration of cinematic possibilities and now reside in the collections of many world-renowned museums. Moreover, his practice is not only limited to filmmaking: as an artist or theoretician he has also worked in architecture, literature, music, painting and cooking. During his time as co-director of the Austrian Film Museum in Vienna, which he founded in 1964, he has passionately dedicated himself to other artistic practices. His formation of the ensemble Spatium Musicum led to an intensive study of essential music, and his teaching on the topic of food preparation as an art form at the Frankfurt School of Fine Arts led to an extension of his title as Professor of Film to that of Film and Cooking. His design for an ideal cinema auditorium, The Invisible Cinema, has been realised in New York and Vienna. Over the past 40 years he has lectured at museums, universities and institutions throughout the world, and has been awarded the Austrian State Prize for his life’s work.

(Mark Webber)

PETER KUBELKA: WHAT IS FILM?

1: THE FILMMAKERS VIEW: THE EVENT OF CINEMA

2: THE MATERIAL OF FILM: TOOL AND PERSONALITY

3: THE LANGUAGE OF FILM: METAPHORS BETWEEN SOUNDS AND IMAGES

4: THE REAL WORLD: A MYTH CREATED BY CINEMA

Date: 8 November 2001 | Season: London Film Festival 2001 | Tags: London Film Festival, Peter Kubelka, What is Film?

PETER KUBELKA: WHAT IS FILM? 1

Thursday 8 November 2001, at 6:35pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

THE FILMMAKERS VIEW: THE EVENT OF CINEMA

“Every endeavour to be objective is personal. I begin my analysis of cinema with the analysis of my own work, which contained my position before I was able to put some of it into words.”

Featuring the following works:

Peter Kubelka, Arnulf Rainer, Austria, 1960, 6m

Peter Kubelka, Schwechater, Austria, 1958, 1m

Peter Kubelka, Adebar, Austria, 1957, 1m

Étienne-Jules Marey, La Chronophotographie, France, 1882–1902, photographic slides

The complete list of films in the repertory, and the themes covered, may be subject to spontaneous change during the course of the presentations.

Date: 8 November 2001 | Season: London Film Festival 2001 | Tags: London Film Festival, Peter Kubelka

IN KUBELKA’S SHADOW

Thursday 8 November 2001, at 9pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

A selection of films by former students of the “Film und Kochen” course at the Staatliche Hochschule für Bildende Künste (Städelschule) in Frankfurt. The shadow of Professor Peter Kubelka looms large over these works by his young protégés, as the films are characterised by an acute attention to detail and by the respect paid to each individual frame. Absolute care is taken with composition while cutting together adjacent shots and in the juxtaposition between sound and image. Several of the films are extraordinary travelogues, covering Romania (Palatca, Frühling 1997), Italy (Mia Zia and Il Palio) and Taiwan (Hwa-Shan-District, Taipei), as alive as the spaces they portray. Turning their attention to the body, Zehetner investigates foot fetishism, and Sackl makes a time-lapse documentation of personal activities, an elementary performance. Metropolen des Leichtsinns uses found footage to consider the possibilities of human experience. Biesendorfer’s films are the most tactile; No Wonder is a directly emotional and explicit diary of life and love.

Bernhard Schreiner, Hwa-Shan-District, Taipei, Germany, 2001, 13 min

Nino Pezzella, Mia Zia, Germany, 1992/2000, 2 x 2 min

Gergard Geiger, Palatca, Frühling 1997, Germany, 2000. 23 min

Georg Wasner, Il Palio, ein Film über die gemeinsame Reise nach Italien, Germany, 1999, 2 x 1 min

Gunther Zehetner, Meine Verehrung, Germany, 2000, 9 min

Thomas Draschan & Ulrich Wiesner, Metropolen des Leichtsinns, Germany, 2000, 12 min

Albert Sackl, Gut Ein Tag Mit Verschiedenem, Germany, 2000, 12 min

Frank Biesendorfer, No Wonder, Germany, 1999, 12 min

Many thanks to Thomas Draschan and Peter Kubelka for their assistance with this programme.

Also screening: Saturday 10 November 2001, at 1:30pm, NFT3

Date: 10 November 2001 | Season: London Film Festival 2001 | Tags: London Film Festival, Peter Kubelka, What is Film?

PETER KUBELKA: WHAT IS FILM? 2

Saturday 10 November 2001, at 4:15pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

THE MATERIAL OF FILM: TOOL AND PERSONALITY

“Film is a transparent sculpture. The material is servant and teacher. Form cannot be transferred and therefore content cannot be transferred. The event of Cinema is unique.”

Featuring selections from the following works:

Emile Cohl, Le Cerceau Magique, France, 1908, 6m

Len Lye, Free Radicals, USA, 1958, 4m

Stan Brakhage, Mothlight, USA, 1963, 3m

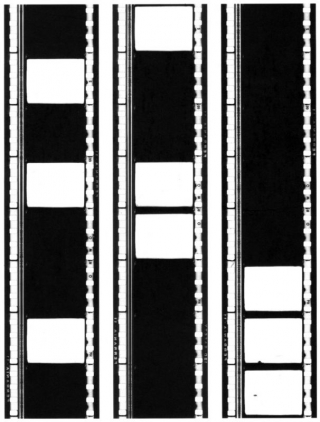

Owen Land (Formerly Known As George Landow), Film in which there Appear Sprocket Holes, Edge Lettering, Dirt Particles, etc., USA, 1965-66, 5m

Karin Hörler, Frisch, Germany, 1987, 2m

Bruce Conner, Valse Triste, USA, 1979, 6m

Frères Lumière, Voltiges, France, 1898, 1m

Frères Lumière, Indochine, Enfants Anamites, France, 1898, 1m

Frères Lumière, La Course en Sacs, France, 1898, 1m

Stan Brakhage, Window Water Baby Moving, USA, 1962, 12m

Paul Sharits, T:O:U:C:H:I:N:G, USA, 1968, 12m

The complete list of films in the repertory, and the themes covered, may be subject to spontaneous change during the course of the presentations.

Date: 12 November 2001 | Season: London Film Festival 2001 | Tags: London Film Festival, Peter Kubelka, What is Film?

PETER KUBELKA: WHAT IS FILM? 3

Monday 12 November 2001, at 6:30pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

THE LANGUAGE OF FILM: METAPHORS BETWEEN SOUNDS AND IMAGES

“Film articulates in metaphors. Between frames, between frames and contemporaneous sounds, between sounds and other sounds brought together by the maker. I will try to make the atoms of film language audible and visible.”

Featuring selections from the following works:

Fernand Léger, Ballet Mecanique, France, 1923-24, excerpt

Robert Breer, Time Flies, USA, 1997, 5m

Dziga Vertov, Enthusiasm, Russia, 1930, excerpt

Paul Sharits, Word Movie, USA, 1966, 4m

Georges Méliès, Le Magicien, France, 1898, 1m

Peter Kubelka, Unsere Afrikareise, Austria, 1966, 12.5m

The complete list of films in the repertory, and the themes covered, may be subject to spontaneous change during the course of the presentations.

Date: 12 November 2001 | Season: London Film Festival 2001 | Tags: London Film Festival

MODERN MEDITATIONS

Monday 12 November 2001, at 9pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

Amid the constantly accelerated media milieu of the modern word, it is fortunately still possible to discover works that demand quiet contemplation, as demonstrated by this selection of predominantly abstract recent film and video. Myriam Bessette, a member of Montréal new media collective Perte-De-Signal, presents a study of the organic aspect of the electronic signal transmission. Bardo by luminary innovator Jordan Belson draws on imagery from his mesmerising and cosmic films of the past. Acting on his instruction, this new work was edited on digital video by his assistant Ying Tan and continues his life-long journey into the transcendent potential of abstraction. While contemplating the “dictatorship of meaning”, Envers provides further proof of Patrice Kirchofer’s command of photography and processing as glimpses of exquisite images briefly emerge from a body of darkness. By applying simple algorithms to visual noise, Bart Vegter created the “cellular automatons” which provide the basis of Forest-Views. The work oscillates between kaleidoscopic colour modulation and the fragile computer generated ‘chemical’ structures that pervade this remarkable film. Joel Schlemowitz offers an homage to colour, set to a poem by Wanda Phipps. Lovesong furthers Brakhage’s exposition of light. Through step-printing and painted filmstrips, he interweaves elaborate biological forms and representations. The final two films both demonstrate a visible admiration for his work; “Anodyne” is a gentle and timeless, melancholic reading, while Notre Icare creates a more contemporary, dynamic impression using music by Autechre.

Myriam Bessette, Nutation, Canada, 2000, 3 min

Jordan Belson, Bardo, USA, 2000, 20 min

Patrice Kirchhofer, Envers, France, 2001, 20 min

Bart Vegter, Forest-Views, Netherlands, 1999, 14 min

Stan Brakhage, Lovesong, USA, 2001, 7 min

Joel Schlemowitz, Morning Poem #40, USA, 2001, 2 min

Sheri Wills, Anodyne, USA, 2001, 4 min

Johanna Vaude, Notre Icare, France, 2001, 8 min

Also screening: Wednesday 14 November 2001, at 1:30pm, NFT3

Date: 14 November 2001 | Season: London Film Festival 2001 | Tags: London Film Festival, Peter Kubelka, What is Film?

PETER KUBELKA: WHAT IS FILM? 4

Wednesday 14 November 2001, at 6:30pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

THE REAL WORLD: A MYTH CREATED BY CINEMA

“Of the world we know only what art has taught us. In the last 100 years cinema has shaped a world, real for us, of which our ancestors could not have dreamed.”

Featuring selections from the following works:

Marie Menken, Go, Go, Go!, USA, 1962-64, 11m

Robert Breer, Eyewash, USA, 1959, 3m

Michael Snow, See You Later / Au Revoir, Canada, 1990, 16m

Fernand Léger, Ballet Mecanique, France, 1923-24, excerpt

Frères Lumière, Demolition D’un Mur, France, 1896, 1m

Georges Kuchar, Hold Me While I’m Naked, USA, 1966, 15m

Georges Kuchar, Wild Night in El Reno, USA, 1977, 6m

Luis Buñuel & Salvador Dalí, L’age D’or, Spain, 1930, excerpt

The complete list of films in the repertory, and the themes covered, may be subject to spontaneous change during the course of the presentations.