Date: 20 November 2007 | Season: The Wire 25

EXTRAORDINARY LIVES

London Roxy Bar and Screen

Tuesday 20 November 2007, at 8pm

Luke Fowler’s Bogman Palmjaguar is a portrait of its namesake, a former patient of radical psychologist R.D. Laing who now lives a hermetic life in the Flow Country of the Scottish Highlands. Documenting the environment of the surrounding landscape as much as its human focus, the images are accompanied by Lee Patterson’s evocative field recordings. Genesis P-Orridge and Lady Jaye are the subjects of Marie Losier’s diary/documentary, which pursues the pandrongynous partners at home, visiting MoMA’s Dada exhibition, and on tour with Thee Majesty and Throbbing Gristle.

Luke Fowler, Bogman Palmjaguar, UK, 2007, 30 min

Marie Losier, A Ballad with Genesis P-Orridge and Lady Jaye, France-USA, 2007, 37 min

PROGRAMME NOTES

EXTRAORDINARY LIVES

London Roxy Bar and Screen

Tuesday 20 November 2007, at 8pm

BOGMAN PALMJAGUAR

Luke Fowler, UK, 2007, video, colour, sound, 30 min

“Bogman Palmjaguar is a portrait of a man who after a series of disturbing events became distrustful of people and withdrew into nature. Bogman describes himself as ‘the hidden cat’ and ‘wild outlaw of paradise’ and is fighting against a diagnosis that that brands him as a ‘paranoid schizophrenic’. Bogman’s early life, and the diagnosis, subsequently conditioned his relationships with others, both within and beyond the medical establishment. The decision to take legal action to remove this label is of paramount importance to him, both as a search for justice and to seek reason in the course his life has taken over the past three decades. The film was shot across two visits to Bogman’s home in a remote village in the north of Scotland. The former was motivated by Bogman’s solicitor’s request of an independent report by Dr. Leon Redler (author and college of R. D. Laing), to assess whether the label ‘paranoid schizophrenic’ was justified. The latter was in collaboration with sound artist Lee Patterson, documenting the environment which Bogman sought to preserve during his time as a conservationist. Bogman had been passionate about the threatened habitat of Scotland’s Flow Country; a wilderness made of blanket bogs and peatlands that houses a unique diversity of wildlife. However the peatlands also became a hide-out, when Bogman fled attempts to section him. The film is a reconciliation of the young conservationist with his older self; isolated and withdrawn from society.” (Luke Fowler)

A BALLAD WITH GENESIS P-ORRIDGE AND LADY JAYE

Marie Losier, USA, 2007, video, colour, sound, 37 min

“I met Genesis by accidentally treading on her feet. I was at an opening in Soho, one of those where you can barely walk and breath and I ended up on her toes. I turned around to apologize and there she was, staring at me smiling with all her golden teeth glittering in my eyes. That’s where it all started. For a while we emailed, learning about each other more and more and one day I ended up in her house, sitting on a giant plastic green chair in the shape of a hand. Since that day I’ve been, in a way, adopted by the family of mom and pop, as Genesis and Lady Jaye call themselves, and by the whole Psychic TV3 band. I’ve been filming them at their home, waking up and going through the routine of being Pandrogynes, which is their main art work today: it’s a living performance in a way. They’ve been having plastic surgery to resemble one another, or rather to be closer to each other in order to break the binary system of male/female, good/bad … creating a third identity that is free from the rules of society. It’s been now a year since I started shooting: they took me on tour in Europe with them, to film them on the routine of the tour. My camera and myself have been totally invited to their life at the rehearsals with the whole band, at home with their favourite person, their dog, Big Boy, with friends, their daughters, going through their incredibly busy daily lifestyles between recording albums, preparing concerts, being in three bands, making art pieces for gallery shows, writing books, doing a raw food diet, shopping for mini skirts, cleaning, and growing their garden in their Bushwick house … there is a lot more I need to capture, but what you will see now is a sort of love ballad for them.” (Marie Losier)

Back to top

Date: 7 March 2008 | Season: Gregory Markopoulos 2008 | Tags: Gregory Markopoulos, Markopoulos

GREGORY J. MARKOPOULOS

7—8 March 2008

London Tate Modern

Gregory J. Markopoulos (1928–1992) was a key figure in the evolution of the New American Cinema of the 1960s, an archetypal personal filmmaker who counted Jack Smith, Kenneth Anger, Stan Brakhage and Maya Deren amongst his contemporaries. His ravishing films are a complex combination of masterful camerawork and editing with a strong vision rooted in myth and poetry.

As his reputation reach its peak, Markopoulos rejected the independent film movement and relocated from New York to Europe in 1967. There, he planned the construction of an archive and projection space – The Temenos – on a remote site in the Greek countryside, a setting that would be in harmony with his extraordinary films.

In his later years, he meticulously edited his life’s work, incorporating over 100 individual titles, into an 80-hour long silent film for presentation only at his chosen location in Arcadia. Since Markopoulos’ death in 1992, the filmmaker Robert Beavers (himself the subject of a Tate Modern retrospective in February 2007) has been working towards the final printing and exhibition of this unique work. The screenings of the first two sections (“orders”) of ENIAIOS took place in 2004 and were commemorated in articles in Artforum, Frieze and Film Comment.

PORTRAITS OF ARTISTS: Friday 7 March 2008

THE ILLIAC PASSION: Saturday 8 March 2008

This rare opportunity to view a selection of Markopoulos’ films in London anticipates TEMENOS 2008; the free, open-air premieres of ENIAIOS III-V that will take place close to the village of Lyssaraia on 27-29 June 2008.

The Tate Modern screenings are curated by Stuart Comer and Mark Webber, and will be introduced by Robert Beavers.

Back to top

Date: 7 March 2008 | Season: Gregory Markopoulos 2008 | Tags: Gregory Markopoulos, Markopoulos

MARKOPOULOS: PORTRAITS OF ARTISTS

Friday 7 March 2008, at 7pm

London Tate Modern

Markopoulos made many extraordinary film portraits, which often incorporate an activity or object that has personal significance to the subject. This programme presents a selection of poetic and sensuous portraits of cultural and art world luminaries such as Gilbert & George, Alberto Moravia, Giorgio di Chirico and Rudolph Nureyev.

Gregory J. Markopoulos, Through A Lens Brightly: Mark Turbyfill, USA, 1967, 15 min

Portrait of Mark Turbyfill

Gregory J. Markopoulos, Eniaios (Order III, Reel 1) (Gibraltar), Switzerland, 1975, 15 min

Portrait of Gilbert & George

Gregory J. Markopoulos, Eniaios (Order IV, Reel 6) (The Olympian), Italy, 1969, 23 min

Portrait of Alberto Moravia

Political Portraits (excerpt)

Gregory J. Markopoulos, Europe, 1969, 15 min

Portraits of Ulrich Herzog, Marcia Haydee, Rudolph Nureyev, Giorgio di Chirico

Gregory J. Markopoulos, Eniaios (Order II, Reel 2), Europe, undated, 23 min

Portraits of Hans-Jakob Siber, Franco Quadri, Giorgio Frapoli, Klaus Schönherr and family

“The films preserve the myriad flights of isolated, spectrally splintered and itinerant spirit, lost in yearning, in search of intuitive wholeness while negotiating mazes of desire, seeking sanctuary in the reflection of countless identities. The works hold a shimmering mirror up to the contradictory compulsions of an era, set to register, for a few instants, shocks of recognition.” (Kirk Winslow, Millennium Film Journal)

The screening will be introduced by Robert Beavers.

Back to top

Date: 27 May 2008 | Season: Videoex 2008 | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT: 1

Tuesday 27 May 2008, at 6pm

Zurich Videoex Festival Cinema Z3

The London Film-Makers’ Co-operative was established in 1966 to support work on the margins of art and cinema. It uniquely incorporated three related activities within a single organisation – a workshop for producing new films, a distribution arm for promoting them, and its own cinema space for screenings. In this environment, Co-op members were free to explore the medium and control every stage of the process. The Materialist tendency characterised the hardcore of British filmmaking in the early 1970s. Distinguished from Structural Film, these works were primarily concerned with duration and the raw physicality of the celluloid strip.

Annabel Nicolson, Slides, 1970, colour, silent, 11 mins (18fps)

Guy Sherwin, At the Academy, 1974, b/w, sound, 5 mins

Mike Leggett, Shepherd’s Bush, 1971, b/w, sound, 15 mins

David Crosswaite, Film No. 1, 1971, colour, sound, 10 mins

Lis Rhodes, Dresden Dynamo, 1971, colour, sound, 5 mins

Chris Garratt, Versailles I & II, 1976, b/w, sound, 11 mins

Mike Dunford, Silver Surfer, 1972, b/w, sound, 15 mins

Marilyn Halford, Footsteps, 1974, b/w, sound, 6 mins

PROGRAMME NOTES

SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT: 1

Tuesday 27 May 2008, at 6pm

Zurich Videoex Festival Cinema Z3

SLIDES

Annabel Nicolson, 1970, colour, silent, 11 mins (18fps)

“A continuing sequence of tactile films were made in the printer from my earlier material. 35mm slides, light leaked film, sewn film, cut up to 8mm and 16mm fragments were dragged through the contact printer, directly and intuitively controlled. The films create their own fluctuating colour and form dimensions defying the passive use of ‘film as a vehicle’. The appearance of sprocket holes, frame lines etc., is less to do with the structural concept and more of a creative, plastic response to whatever is around.” (Annabel Nicolson, LFMC catalogue 1974)

AT THE ACADEMY

Guy Sherwin, 1974, b/w, sound, 5 mins

“Makes use of found footage hand printed on a simple home-made contact printer, and processed in the kitchen sink. At The Academy uses displacement of a positive and negative sandwich of the same loop. Since the printer light spills over the optical sound track area, the picture and sound undergo identical transformations.” (Guy Sherwin, LFMC catalogue 1979)

SHEPHERD’S BUSH

Mike Leggett, 1971, b/w, sound, 15 mins

“Shepherd’s Bush was a revelation. It was both true film notion and demonstrated an ingenious association with the film-process. It is the procedure and conclusion of a piece of film logic using a brilliantly simple device; the manipulation of the light source in the Film Co-op printer such that a series of transformations are effected on a loop of film material. From the start Mike Leggett adopts a relational perspective according to which it is neither the elements or the emergent whole but the relations between the elements (transformations) that become primary through the use of logical procedure.” (Roger Hammond, LFMC catalogue supplement, 1972)

FILM NO. 1

David Crosswaite, 1971, colour, sound, 10 mins

“Film No. 1 is a 10-minute loop film. The systems of super-imposed loops are mathematically inter-related in a complex manner. The starting and cut off points for each loop are not clearly exposed, but through repetitions of sequences in different colours, in different ‘material’ realities (i.e. a negative, positive, bas-relief, neg-pos overlay) yet in constant rhythm (both visually and on the soundtrack hum) one is manipulated to attempt to work out the system structure … The film deals with permutations of material, in a prescribed manner but one by no means ‘necessary’ or logical (except within the film’s own constructed system/serial.)” (Peter Gidal, LFMC catalogue 1974)

DRESDEN DYNAMO

Lis Rhodes, 1971, colour, sound, 5 mins

“This film is the result of experiments with the application of Letraset and Letratone onto clear film. It is essentially about how graphic images create their own sound by extending into that area of film which is ‘read’ by optical sound equipment. The final print has been achieved through three separate, consecutive printings from the original material, on a contact printer. Colour was added, with filters, on the final run. The film is not a sequential piece. It does not develop crescendos. It creates the illusion of spatial depth from essentially, flat, graphic, raw material.” (Tim Bruce, LFMC catalogue 1993)

VERSAILLES I & II

Chris Garratt, 1976, b/w, sound, 11 mins

”For this film I made a contact printing box, with a printing area 16mm x 185mm which enabled the printing of 24 frames of picture plus optical sound area at one time. The first part is a composition using 7 x 1-second shots of the statues of Versailles, Palace of 1000 Beauties, with accompanying soundtrack, woven according to a pre-determined sequence. Because sound and picture were printed simultaneously, the minute inconsistencies in exposure times resulted in rhythmic fluctuations of picture density and levels of sound. Two of these shots comprise the second part of the film which is framed by abstract imagery printed across the entire width of the film surface: the visible image is also the sound image.” (Chris Garratt, LFMC catalogue 1978)

SILVER SURFER

Mike Dunford, 1972, b/w, sound, 15 mins

“A surfer, filmed and shown on tv, refilmed on 8mm, and refilmed again on 16mm. Simple loop structure preceded by four minutes of a still frame of the surfer. An image on the borders of apprehension, becoming more and more abstract. The surfer surfs, never surfs anywhere, an image suspended in the light of the projector lamp. A very quiet and undramatic film, not particularly didactic. Sound: the first four minutes consists of a fog-horn, used as the basic tone for a chord played on the organ, the rest of the film uses the sound of breakers with a two second pulse and occasional bursts of musical-like sounds.” (Mike Dunford, LFMC catalogue supplement 1972)

FOOTSTEPS

Marilyn Halford, 1974, b/w, sound, 6 mins

“Footsteps is in the manner of a game re-enacted, the game in making was between the camera and actor, the actor and cameraman, and one hundred feet of film. The film became expanded into positive and negative to change balances within it; black for perspective, then black to shadow the screen and make paradoxes with the idea of acting, and the act of seeing the screen. The music sets a mood then turns a space, remembers the positive then silences the flatness of the negative.” (Marilyn Halford, LFMC catalogue 1978)

Back to top

Date: 30 May 2008 | Season: Videoex 2008

SOCIAL WORKS: NEW DOCUMENTARY FORMS

Friday 30 May 2008, at 4pm

Zurich Videoex Festival Cinema Z3

Long before the celebrated ‘Free Cinema’ movement of the 1950s, British-based filmmakers were advancing the documentary form through innovative styles and techniques. Beginning with a hilariously absurd travelogue from 1924, this programme traces that development through good times and bad, resolute with humour and irony.

Adrian Brunel, Crossing the Great Sagrada, 1924, 35mm, tinted b/w, sound, 10 min

Arthur Elton & E.H. Anstey, Housing Problems, 1935, 35mm, b/w, sound, 13 min

Stefan & Franciszka Themerson, Calling Mr Smith, 1943, 35mm, colour, sound, 10 min

Len Lye, N or NW, 1938, 35mm, b/w, sound, 8 min

Charles Ridley, Germany Calling, 1941, 16mm, b/w, sound, 2 min

Claude Goretta & Alan Tanner, Nice Time, 1957, 16mm, b/w, sound, 17 min

John Bennett, Papercity, 1969, 35mm, colour, sound, 5 minutes

PROGRAMME NOTES

SOCIAL WORKS: NEW DOCUMENTARY FORMS

Friday 30 May 2008, at 4pm

Zurich Videoex Festival Cinema Z3

CROSSING THE GREAT SAGRADA

Adrian Brunel, 1924, 35mm, tinted b/w, sound, 10 min

The film is a humorous spoof of a travelogue. Travel films were popular in the Twenties, documenting foreign cultures in a way that tended to reflect imperial, nationalist and often racist stereotypes. Brunel sends up many of the conventions of the genre familiar to audiences. (Jamie Sexton)

HOUSING PROBLEMS

Arthur Elton & Edgar Anstey, 1935, 35mm, b/w, sound, 13 min

A watershed in British documentary making. For the first time ordinary people spoke directly to the camera about their plight. The clumsy sound-recording equipment (packed into a truck parked outside the locations in Stepney) enabled the directors to achieve huge impact by filming the slum dwellers as they described life inside their wretched houses. The film was made to promote the use of gas as a clean and modern fuel by associating it with the throwing out of the old and the building of the new. (FourDocs)

CALLING MR SMITH

Stefan & Franciszka Themerson, 1943, 35mm, colour, sound, 10 min

The Themersons call on ‘Mr Smith’ to support the war effort as an anti-fascist struggle, illustrating its appeal with examples of Nazi oppression in Poland. The film is experimental in technique, using anamorphic lenses, still and moving images and vivid colour. While the spoken soundtrack employs a rhetoric heard elsewhere in wartime propaganda, the overall tone of the film is unusually urgent and authentic and in some sequences, images combine with music (Chopin, Szymanowski) to convey a real feeling of loss. (David Finch)

N or N.W.

Len Lye, 1938, 35mm, b/w, sound, 8 min

In N or N.W., Lye began to work with more conventionally ‘dramatic’ material. The film, advertising the benefits of writing letters and using the postal system, centred on a simple narrative of lovers at cross-purposes who are eventually reunited. Yet Lye used a number of unconventional edits, extreme close-ups, trick shots and superimposed animation in order to take a creative approach to such a conventional theme. (Jamie Sexton)

GERMANY CALLING

Charles Ridley, 1941, 35mm, b/w, sound, 2 min

A remarkable piece of British wartime propaganda which ridicules Nazi Germany by manipulating footage of Hitler, his party officials and troops of goose stepping soldiers. All are subjected to the optical humiliation of being made dance to the ‘The Lambeth Walk’, a song that the Nazi party branded as ‘Jewish mischief and animalistic hopping.’ (MW)

NICE TIME

Claude Goretta & Alan Tanner, 1957, 16mm, b/w, sound, 17 min

Impressions of Piccadilly Circus in 1957: hot dogs and nude magazines; dumb cinema queues; posters advertising the glories of war and the horrors of science fiction; lonely faces; searching glances; the parade of amateur and professional ‘talent’; presiding over all, the ironic statue of Eros … The observation is untouched by nostalgia, and presents a devastating picture for anyone who thinks of Piccadilly Circus in romantic terms. (Monthly Film Bulletin)

PAPERCITY

John Bennett, 1969, 35mm, colour, sound, 5 min

Papercity builds an impressionistic portrait of London through still photographs and time-lapse footage. Views of the city rarely feature in experimental films of this period, but this semi-commercial production, funded by the British Film Institute, is an evocative study of everyday sights and activities. (MW)

Back to top

Date: 13 June 2008 | Season: Tony Conrad | Tags: Tony Conrad

TONY CONRAD

13—15 June 2008

London Tate Modern

Tony Conrad is a pivotal figure in contemporary culture. His multi-faceted contributions since the 1960s have influenced and redefined music, filmmaking, minimalism, performance, video and conceptual art. Known for his groundbreaking film The Flicker, his involvement in the Theatre of Eternal Music and the evolution of the Velvet Underground, and collaborations with a host of luminaries including Jack Smith, John Cale, Mike Kelley and Henry Flynt, Conrad remains a radical figure who challenges our understanding of art history. This special weekend at Tate Modern will feature a major new performance for the Turbine Hall and screenings of Conrad’s extraordinary film and video work.

Curated by Stuart Comer, Alice Koegel and Mark Webber. Assistant Curator Vanessa Desclaux.

With thanks to Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Cologne; Ed Carter, Lumen/Evolution; Tracey Ferguson; Florian Härle; Tony Herrington, The Wire; Branden W. Joseph; Christophe Kniel and Ilja Mess; Neil Lagden; Elliot Landy; David Leister; Marie Losier; Eric Namour, [no.signal]; Jay Sanders, Greene Naftali Gallery, New York; Chloë Stewart; Ann Twiselton, MIT Press; Steve Wald; Richard Whitelaw, Sonic Arts Network.

INTRODUCTION

TONY CONRAD

Friday 13 – Sunday 15 June 2008

London Tate Modern

Tony Conrad is a pivotal, polymath figure in contemporary culture, a pioneering composer, musician, performer and filmmaker, whose work emerged at the heart of New York’s fervent avant-garde art community in the early 1960s. Best known for his influential early musical explorations and the ‘experiential excess’ of his groundbreaking ‘structural film’, The Flicker, Conrad’s work offers a complex reassessment of duration and temporality, and a direct implication of the viewer as an active participant in his work. His hybrid, often perceptually intense practice has persistently expanded disciplinary boundaries and challenged traditional notions of authorship and authority for more than forty years.

After studying mathematics at Harvard, during the early 1960s Conrad developed a distinct approach to sound in contemporary musical production, introducing sustained drones built upon a strategy of minimal reduction and temporal expansion. From 1962 he was a key member of the groundbreaking Theatre of Eternal Music (also known as The Dream Syndicate). The group developed ‘Dream Music’ which dispensed with written scores and critiqued the history of western orchestral performance. Utilising long durations, precise pitch and blistering volume, its members – including Conrad, La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela and future Velvet Underground co-founders John Cale and Angus MacLise – forged a performance collaboration which denied the activity of composition, examined the physical elements of sound, and established a principal branch of the minimalist tradition. Following the dissolution of the group in 1965, Conrad has continued to reflect on duration as a concept in various fields conventionally distinguished as music, film, performance and the visual arts, always challenging his audience in whatever medium he employs.

Throughout his career Conrad has sought ‘physiological and psychological phenomena’ that produce a profound interaction with the audience. The stroboscopic, psychedelic intensity of films like The Flicker and the saturated energy and long duration of Conrad’s music can become powerful, moving and unsettling experiences that heighten awareness both of the physical experience of the event and of one’s own subjectivity within it. Carrying over from one medium to another, Conrad sets up situations that encourage free experiences of audiovisual perception and perceptual engagement, ‘manufacturing the culture as the event proceeds, as the context sustains.’

Much of Conrad’s work has involved collaboration, from the Theatre of Eternal Music to his involvement with the philosopher, musician and anti-art activist Henry Flynt, his early creative partnership with the underground artist and filmmaker Jack Smith, his participation in the influential Department of Media Study at the State University of New York at Buffalo, and more recent projects with artists such as Mike Kelley and Tony Oursler. As his career has shifted and intersected with these diverse artists, agendas and positions, Conrad has problematised not only his own work but the conventional set of categories used to contain and define it. A reconsideration of his practice also problematises traditional linear histories of the movements and developments with which he has been associated: minimalism, Fluxus, early conceptualism, underground and structural film, paracinema or expanded cinema, performance and video. The heterogeneous nature of Conrad’s work comprises a radical and productive inconsistency that continues to subvert the power structures that regulate the writing of history.

Conrad’s approach to cinema reflects his penchant for transcending boundaries and reconfiguring conventional notions of production. The Flicker, his rallying call for a new age of cinema, led the philosopher Gilles Deleuze to muse on a ‘cinema of expansion without camera, and also without screen or film stock,’ a cinema in which ‘anything can be used as a screen, the body of a protagonist or even the bodies of the spectators; anything can replace the film stock, in a virtual film which now only goes on in the head, behind the pupils.’ Conrad’s films do not rely only on luminous, audiovisual stimulation and extreme perceptual states. He has also explored a wide range of unusual materials and production methods, experimenting with various ways of cooking film – treating raw film stock as an ingredient to be stir-fried or pickled, and then projected. He has also played film as a musical instrument, stretched taut and played upon with a bow, and has used a Tesla coil to electrocute film stock.

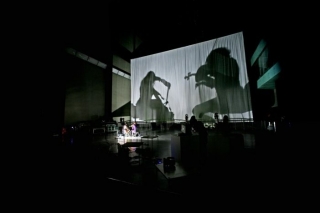

This theatrical, performative approach to creating films makes process and production an integral and evident part of the work. The relationships between process, projection and performance have a long history within Conrad’s work and take on particular resonance in Early Minimalism, a series of compositions which refer to and redress the artist’s history with the Theatre of Eternal Music. Performances take place behind a scrim, backlit to create shadows of the performers, a spectral doubling to complicate the work’s relationship to the past.

Unprojectable: Projection and Perspective, a new commission in which Conrad addresses the immense space of Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall with its central bridge as a stage, exposes us to his most recent exploration of projection and long duration on a major scale. A tremendous sound will fill the Turbine Hall, starting off with a buzzing pulse at 25 per second, mixed with an amplified string quartet including Conrad on violin, an electric drill and hand-held phonograph arms. Billowing scrims on either side of the bridge function as projection screens for the performative activities enacted behind them. These actions will include the live music performance and re-enactments of alternative film production processes Conrad developed in the mid-1970s, such as drilling holes in raw film stock. While the audience occupies the floor below, Conrad’s back-projected, larger-than-life silhouette will loom large, swaying in response to the production of sounds which will generate a pressure-filled auditory environment. The intensity of the sound will ground the event in the physical and perceptual space of the present, while the shadows might be read as a comment on the status of the present versus the re-presented and non-recoverable past in the archive of musical and visual culture.

—Stuart Comer, Tate Modern, Curator: Film

—Alice Koegel, Tate Modern, Curator: Contemporary Art and Performance

Back to top

Date: 13 June 2008 | Season: Tony Conrad | Tags: Tony Conrad

TONY CONRAD: FLICKER AND PROCESS FILMS

Friday 13 June 2008, at 7pm

London Tate Modern

Minimal cinema with maximal effect. Few films provide the intense, stroboscopic viewing experience of The Flicker, a non-objective film composed only of opaque and clear frames, and a pulsing electronic soundtrack. Conrad’s cinematic debut still astounds audiences four decades after its creation, and will be screened together with other works exploring audio-visual harmonics and the radical production processes of cooked and electrocuted films.

The screening, introduced by Tony Conrad, will be followed by a reception to celebrate the publication of “Beyond the Dream Syndicate” (Zone Books/MIT).

Tony Conrad, The Flicker, 1966, 30 min

Tony Conrad, Curried 7302, 1973, 2 min

Tony Conrad, 7302 Creole, 1973, 1 min

Tony Conrad, 4-X Attack, 1973, 2 min

Tony Conrad, Film Feedback, 1974, 14 min

Tony Conrad, Articulation of Boolean Algebra for Film Opticals, 1975, 10 min excerpt

Tony Conrad, The Eye of Count Flickerstein, 1967/75, 7 min

Beverly & Tony Conrad, Straight and Narrow, 1970, 10 min

PROGRAMME NOTES

TONY CONRAD: FLICKER AND PROCESS FILMS

Friday 13 June 2008, at 7pm

London Tate Modern

THE FLICKER

Tony Conrad, USA, 1966, 16mm, b/w, sound, 30 min

I think that The Flicker acts as a very versatile art object. The observer can really use it to his own means over a wide range of possibilities. The beauty lies within the beholder himself. In most aesthetic presentations – drama, cinema, music – the common attitude is that the amusement or the beauty or the effect of the experience is wholly within the entertainer; that the entertainer is actually creating the impressions or the reaction himself. The Flicker, I think, presents a clean-cut case of the experience lying within the observer. Most of the details, most of the impact, most of what people find it in, what they take away from having watched the film, wasn’t there, was conjured up only when they watched this film: it didn’t exist before, it doesn’t exist on film, it wasn’t on the screen.

CURRIED 7302

Tony Conrad, USA, 1973, 16mm, colour, silent, 2 min

Conrad began a series of ‘Cooked Films’ in 1973. Folding social and political concerns into the process in an explicit manner, Conrad – who at the time was serving as primary caregiver to his child, as well as professor of film at Antioch – adapted the practice of filmmaking to the stereotypically female role of domestic cook. Usually substituting ‘raw’ film in the place where different recipes called for onions, Conrad ‘processed’ the footage in various manners on his countertop or stove, with the result being, as Conrad recalled about Curried 7302 (1973), “this gorgeous mottled yellow, abstract thing.” (Branden Joseph

7302 CREOLE

Tony Conrad, USA, 1973, 16mm, colour, silent, 1 min

The second work in the series was a film chicken creole, the projection of which caused – through the thick alimentary residue still clinging to the celluloid – gate slipping and other effects simulated in structural films. “Well, this was very interesting because the meat ran all over the projector, and it was full of grease and chicken. It slipped in the gate, and it stunk because the lamp heated it up, and it was really like an olfactory experience, and it tested the skill of the projectionist, who is covered in slime …” (Branden Joseph

4-X ATTACK

Tony Conrad, USA, 1973, 16mm, b/w, silent, 2 min

Foregrounding the manner in which film could be ‘exposed’ and developed via heat, pressure, or electricity, rather than merely by light and developer fluid, Conrad produced a ‘material’ paracinema. In 4-X Attack, he struck a roll of celluloid with a hammer in a darkroom. “The material being brittle,” Conrad noted, “it was not only left with stress-bearing deformations, but was compressed in points, scraped and sheared in others, and generally speaking completely totalled.” Once the film was fractured into myriad pieces, Conrad swept them back together, “flashed the film once with a strobe, so as to activate the latent stress record,” developed it in a cheese cloth sack, and then painstakingly, even archeologically, reconstructed the roll (it is, afterall, an ‘edited’ film) into a projectable movie.” (Branden Joseph

FILM FEEDBACK

Tony Conrad, USA, 1974, 16mm, b/w, silent, 14 min

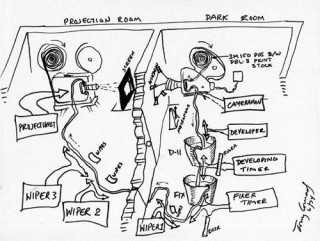

The cybernetics of video applied to film production. Film Feedback was produced in ‘real time’ by processing and projecting the film while it was being shot. Made with a film-feedback team which I directed at Antioch College. Negative image is shot from a small rear-projection screen, the film comes out of the camera continuously (in the dark room) and is immediately processed, dried, and projected on the screen by the team. What are the qualities of film that may be made visible through feedback?

ARTICULATION OF BOOLEAN ALGEBRA FOR FILM OPTICALS

Tony Conrad, USA, 1975, 16mm, b/w, sound, 75 min (10 min excerpt)

The work that served for me as a checkmate in the ‘structural’ film game is Articulation of Boolean Algebra for Film Opticals. This film achieved something of an apogee in formalist design, that conceptual regimentation which, in relation to de Sade’s eroticism, Barthes called “encyclopaedic […] the same inventorial spirit which animates Newton or Fourier.” (The Metaphor of the Eye, 1963.) Articulation literally unifies the optical and sound tracks. Both are the result of a design that follows an algorithmic system of stripes. The scale of the six stripes on the film strip positions them in relation to screen design, flicker, tone, rhythm, and meter, all with octave relationships.

THE EYE OF COUNT FLICKERSTEIN

Tony Conrad, USA, 1967/75, 16mm, b/w, silent, 7 min

The sustained dead gaze of black and white TV ‘snow’, captured in 1965 and twisted sideways, draws the viewer hypnotically into an abstract visual jungle.

STRAIGHT AND NARROW

Beverly & Tony Conrad, USA, 1970, 16mm, b/w, sound, 10 min

Straight and Narrow is a study of subjective colour and visual rhythm. Although it is printed on black and white film, the hypnotic pacing of the images will cause most viewers to experience a programmed gamut of hallucinatory colour effects. Through the intermediary of rhythm, the maximal impact is drawn from the simplest of universal human images: straight horizontal and vertical lines.

All texts or quotes by Tony Conrad unless otherwise noted. Texts by Branden Joseph have been adapted from “Beyond the Dream Syndicate: Tony Conrad and the Arts After Cage” (Zone Books / MIT Press).

Back to top

Date: 14 June 2008 | Season: Tony Conrad | Tags: Tony Conrad

TONY CONRAD TAKES ON VIDEO

Saturday 14 June 2008, at 6pm

London Tate Modern

WHO’S WATCHING WHO?

Tony Conrad investigated the conditions of video production and presentation in a series of tapes which deconstruct or re-appropriate the techniques of TV. Exploiting the reflexive nature of the medium, he critiques the electronic image and notions of history, theory and authority with an irreverent sense of humour. Postmodernism was never this much fun! The artist will introduce this programme of rarely seen works.

Tony Conrad, Concord Ultimatum, 1977, 10 min excerpt

Tony Conrad, Redressing Down, 1988, 18 min

Tony Conrad, Ipso Facto, 1985, 7 min

Tony Conrad, Lookers, 1974, 4 min excerpt

Tony Conrad, Egypt 2000, 1986, 13 min

Tony Conrad, No Europe, 1990, 13 min

Tony Conrad, Accordion, 1981, 5 min

Tony Conrad, In Line, 1986, 7 min

PROGRAMME NOTES

TONY CONRAD TAKES ON VIDEO: WHO’S WATCHING WHO ?

Friday 13 June 2008, at 7pm

London Tate Modern

CONCORD ULTIMATUM

Tony Conrad, USA, 1977, video, b/w, sound, 35 min (10 min excerpt)

In Concord Ultimatum, I bend the structuralist / materialist film idiom in the direction of narrative, by addressing the video apparatus, the camera, directly. Materialist films were structured around a frank recognition of the primacy of the cinematic apparatus, but the recognition itself of this materialism required critical assessment; that is, a hidden stage of the materialist work, virtual to the work itself, is its identification and assessment as materialist. In Concord Ultimatum I hoped to assimilate the critical stage into the work, by repositioning the conditions of representation in the virtual space of audience reception.

REDRESSING DOWN

Tony Conrad, USA, 1988, video, colour, sound, 18 min

Redressing Down uses the distance between the body and architectural / environmental space as a metaphor for the relationship between maker and viewer. It invokes the body in relation to personal living space, in that personal space constructs an essential site for mediated social activity. A series of vignettes, each of which grips the viewer in a setting of psychic expectancy, constructs a psychological and cultural ‘virtual reality’, each viewer’s feedback into the video is their own theatrical construction of the tape’s events.

IPSO FACTO

Tony Conrad, USA, 1985, video, colour, sound, 7 min

A story of technology, appropriation, and authority. High technology is a palisade of errors behind which artists are marionettes of industry or addicts of solitaire. Inappropriate appropriation abounds here – inappropriate because what’s quoted is either not an entry in the cultural ark(ive) or is vulnerable to criticism. Then there’s the completely untrustable face, a pasty puffy morning after case, an old futz that nobody would ever believe, who mouths quotes from Mussolini (an authority no one can take seriously, the most maligned and possibly least acceptable thinker of the century), and who looks out from his monitor upon an old-fashion audience that listens unblinkingly, without a peep or guffaw.

LOOKERS

Tony Conrad, USA, 1984, video, colour, sound, 4 min (pilot segment)

An analytical crisis ensues when the viewer’s activity is accounted within the work: without a (historic) closure, there can be no criteria of quality, nor a universal reference for judgement. Postmodern discourse has at least made a down payment on this cost to theory. Lookers seeks a different answer by moving against the tide; it explores the inclusion of discipline itself within the realm of interactions which encompass the work and viewer. In this fragment, there is a stress on the visual perceptual mode. Other footage expands Lookers into other sensory modalities, and implements a more alluring discipline.

EGYPT 2025

Tony Conrad, USA, 1986, video, colour, sound, 13 min (work in progress)

The First Intermediate Period was the occasion for a remarkable constellation of innovations in Egyptian thought and civil order. After the death of Pepy the First, none of the numerous claimants to his sacred throne was able to reverse the dire drought that announced the modern incursions of the Sahara into Egypt; one after another they were secretly denounced and executed; and simultaneously Egypt was visited by refugees filtering in across the eastern and western sands. Local nobles were unopposed in their power, and they attained to the same privileges as pharaoh in the afterworld (‘the West’). For the first time men and women too won rights of private ownership, of contracted marriages, and (with a proper burial) of entry to the West. Remarkably, individuals began reflecting in writing on the world around them, and the first introspective literature was invented. Egypt 2025 immerses itself in this concatenation of catastrophes, which is elaborated across the mixed space of family, gender, writing, law, civil order, religion, personal identity, and death. Any historical complex is simultaneously an invocation of our own condition, the conviction that sustains ’history’ as narrative arises amid the multiplication of overdetermining details that compose its ‘authenticity’.

NO EUROPE

Tony Conrad, USA, 1990, video, colour, sound, 13 min

Science fiction can invent a ‘future’ in a way that historical romances are not permitted to do. No Europe violates this convention, freely projecting a past in which the ‘white man’ (and woman) in America was not from Europe at all, but instead has somehow derivatived from a primitive cave-dwelling condition to which ‘Caucasians’ would have been weirdly ill adapted, since they would have received no assistance, as the historical Europeans did, from Indians – a people whom we are led to understand may instead have been living in Europe. Needless to say, this script is rife with rudeness and inconsistency.

ACCORDION

Tony Conrad, USA, 1981, video, colour, sound, 5 min

Around 1958 or 1959 Henry Flynt and I did a public performance of a Duo by Christian Wolff on two violins. Henry was an able performer; I, on the other hand, was not. My tone was shrill and thin, without the warmth of vibrato or the nuanced bowing that comes with long practice. Nevertheless, the ‘lesson’ of John Cage’s music was the equivalence of all sounds, and for me the successful testing of this notion against the amateurism of my own practice was a fascinating confirmation of my forwardness in ‘going public’ as a musician. Henry informed me that in fact Christian particularly liked the qualities of our performance. This attitude, which in effect accepted (or even found substantial interest in) amateurism in musical performance, was significant for me in releasing my self-assurance as a performer. From this point forward I was comfortable with, and even preferential toward, amateurism in performance. In 1980, I made Accordion, a video performance that caricatured inept performance as a heroic enterprise.

IN LINE

Tony Conrad, USA, 1986, video, colour, sound, 7 min

A trisection of the spectator’s power over their own image language: word, trance, and command are installed as valences of the artist’s license; revealed as figures of parental authority. How peculiar that people like being an audience because they enjoy their submission to the authority of the program. This ritual of being dominated is a conspiracy with themselves that we enjoy but refuse to acknowledge. “Oh, no. I don’t like TV because I’m submissive; it’s because it makes me feel good.” The programs are always carefully crafted to be sensitive to people’s self-protectiveness, even if they offer a good scare, or a good cry. Well, if this is all true, what happens when, by chance, you submit to a program that refuses to be polite about your closet masochism? That … tells all? In the wake of Combat Status Go, and in the course of making the trilogy “The Poetics of TV” (which comprises Ipso Facto, An Immense Majority and In Line), I discovered that meta-narrative devices could be employed ironically – even perniciously. Even an ‘advanced’ viewer might not have a chance to enjoy full independence from the strictures of the work, but they would enjoy the demonstration of their encumbrance by older viewing habits (or one might say the deconstruction of narrative conceits), to the extent that they found themselves trapped by the unravelling devices of these three short tapes.

All texts or quotes by Tony Conrad.

Back to top

Date: 14 June 2008 | Season: Tony Conrad | Tags: Tony Conrad

UNPROJECTABLE: PROJECTION AND PERSPECTIVE

Saturday 14 June 2008, at 10pm

London Tate Modern

This major new live performance by Tony Conrad is especially conceived for the latent sound and immense scale of the Turbine Hall. Emerging from an installation inspired by the hum of the former power station’s one remaining generator, Conrad’s sonic and visual feast will incorporate an amplified string quartet, electric drill and motors, phonograph arms, film projection and shadows which loom high above the audience.

Conceived and performed by Tony Conrad.

MV Carbon, cello

Tony Conrad, violin

Angharad Davies, violin

Dominic Lash, bass

Steve Wald, production manager

Delta Sound, sound design

Chloë Stewart, projection

This is a free event as part of UBS Openings: Saturday Live.

Back to top

Date: 19 September 2008 | Season: Ken Jacobs tank.tv | Tags: Ken Jacobs, tank.tv

RETURN TO THE SCENE OF THE CRIME

Friday 19 September 2008, at 7pm

London Tate Modern

In a contemporary riff on one of his landmark works, Ken Jacobs uses new technology to both interrogate and arouse a theatrical tableau, shot in 1905, based on Hogarth’s Southwark Fair. The antique film print is probed, exploded and reconstituted in the digital domain with radical ingenuity and infectious wit. This extraordinary new work teaches us how to see.

Ken Jacobs, Return to the Scene of the Crime, USA, 2008, video, colour, sound 92 min

“The heartwarming story of a boy who didn’t know it’s wrong to steal. Running off with the pig seemed like a good idea at the time.”

More than theft of a pig is taking place at Southwark Fair. Why does God, right there amongst the crowd, allow this cheery riffraff such liberties? I haven’t been so shocked since 1969, when I first examined this primitive 1905 movie with my camera (Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son, added in 2007 to the Library of Congress National Film Registry). A better print of the original film, and the power of the computer, allows for deeper and more detailed inspection. Forensic cinema at its most obsessive, the dead rise … and prove quite entertaining.

Curated by Mark Webber for tank.tv and Tate Modern. An online exhibition at www.tank.tv from 1 October to 30 November 2008 includes a selection of 20 complete or excerpted works by Ken Jacobs, dating from 1956 to the present.