Date: 17 October 2001 | Season: Cinema Auricular

SEEING SOUND: LIGHTNING STRIKES THE OPTIC NERVE

Wednesday 17 October 2001, at 7:30pm

London Barbican Cinema

Optical sound on 16mm film – a lightbulb reads a strip of amorphous black emulsion on clear celluloid and it somehow makes sound sense. Since the 1930s artists have examined and exploited the possibilities of drawing or printing a soundtrack. Two senses combined and confounded, both musical and cacophonous. Can you see what you hear?

Oskar Fischinger, Ornament Sound, 1932, 7 min

Norman McLaren, Dots (Points), 1948, 3 min

Barry Spinello, Soundtrack, 1969, 10 min

Richard Reeves, Linear Dreams, 1997, 7 min

Pierre Rovere, Black and Light, 1974, 8 min

Lis Rhodes, Dresden Dynamo, 1974, 5 min

Chris Garrett, Exit Right, 1976, 3 min

Jun’ichi Okuyama, My Movie Melodies, 1980, 7 min

Guy Sherwin, Musical Stairs, 1977, 10 min

Peter Tscherkassky, L’Arrivée, 1998, 3 min

Taka Iimura, Shutter, 1971, 22 min

Screening introduced by filmmaker Guy Sherwin.

PROGRAMME NOTES

SEEING SOUND: LIGHTNING STRIKES THE OPTIC NERVE

Wednesday 17 October 2001, at 7:30pm

London Barbican Cinema

ORNAMENT SOUND

Oskar Fischinger, Germany, 1932, b/w, sound, 7 min

‘You ear what you see, you see what you ear’. Indeed, on the left side of the image, unravelling vertically, is the synchronised drawing of the sound wave that is heard. Along the drawing of these sound waves moving small rectangles with appear each new sound level, indicating the height of the note produced in conventional notation, for example C#4 for ‘Do #’ in the fourth octave on the piano. Tönnende Ornamente thus presents the spectral range of the synthetic sound to us. At the beginning of film a falling scale explores the low register, followed by a perambulation of an octave in the acute part of the sound spectrum. Fischinger also presents the various stamps and types of attack which one can obtain with the optical sounds. (Philippe Langlois)

DOTS (POINTS)

Norman McLaren, Dots (Points), Canada, 1948, colour, sound, 3 min

This film of geometric abstractions drawn directly on the film with pen and ink was made independently by McLaren. Exploring the synchronisation of the visuals with a synthetic soundtrack, McLaren drew a percussive rhythm of clicking sounds along the edge of the film. The soundtrack reveals how early in his career McLaren achieved a sophistication in the use of this method. The music ranges over several octaves, integrating perfectly with the moving blue and white dots that flip across the screen on a red background. (Maynard Collins)

SOUNDTRACK

Barry Spinello, Soundtrack, USA, 1969, b/w & colour, sound, 10 min

John Cage wrote, in 1938, of a “new electronic music” to be developed out of the photoelectric cell optical-sound process used in films. Any image – his example is a picture of Beethoven – or mark on the soundtrack, successively repeated, will produce a distinct pitch and timbre. This new music, he said, would be built along the lines of film, with the basic unit if rhythm logically being the frame. However, with the subsequent development of magnetic tape a few years later (and the advantages it has in convenience, speed, capacity to record, erase and playback live sound), the filmic development of electronic music initially envisioned by Cage was obscured. Had magnetic record tape never been invented, undoubtedly a rich new music would have developed via optical sound means, and composers would have found ways to work with film.

LINEAR DREAMS

Richard Reeves, Canada, 1997, colour, sound, 7 min

In Linear Dreams, Richard Reeves explores new realms of the imagination. The piece begins with a line pulsing to a heartbeat -the base for all living things. Images then explode and implode until they are released from the human form, expand outward over a vast mountain range, and then return to their origin. Reeves’ hand-drawn soundtrack underscores Linear Dreams, creating a multiple award-winning piece filled with rhythmic electricity.

BLACK AND LIGHT

Pierre Rovere, Black and Light, France, 1974, b/w, sound, 8 min

This film was directly executed on computer without cinematographic intervention or equipment. It is not the communication of a movement, but a succession of facts made up that the device of projection translated for us into impressions of movements. This film does not refer to an external reality, but wants to be its own reality.

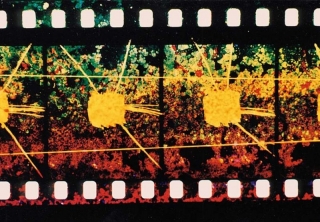

DRESDEN DYNAMO

Lis Rhodes, UK, 1974, colour, sound, 5 min

The result of experiments with the application of Letraset and Letratone onto clear film. It is essentially about how graphic images create their own sound by extending into that area of film which is ‘read’ by optical sound equipment. The final print has been achieved through three separate, consecutive printings from the original material, on a contact printer. Colour was added with filters on the final run. The film is not a sequential piece. It does not develop crescendos. It creates the illusion of spatial depth from essentially flat, graphic, raw material. (Tim Bruce)

EXIT RIGHT

Chris Garrett, Exit Right, UK, 1976, b/w, sound, 3 min

A one second shot of me walking into the shot wearing a striped jersey was printed repeatedly. This strip of negative was moved laterally across the printer every ten seconds of film time, so that the image of the piece of film material, containing its figurative image moves into the projected frame from the left, across the frame and out across the optical soundtrack area to the right. Featuring a new line in Musical Pullovers.

MY MOVIE MELODIES

Jun’ichi Okuyama, Japan, 1980, b/w, sound, 7 min

In this film, the image produces the sound, and the sound is the image. It catches sight of landscapes and incidents. The various images are used to cover an extensive range of sounds. The principal melody is a radiograph of a comb.

MUSICAL STAIRS

Guy Sherwin, UK, 1977, b/w, sound, 10 min

I shot the images of a staircase specifically for the range of sounds they would produce. I used a fixed lens to film from a fixed position at the bottom of the stairs. Tilting the camera up increases the number of steps that are included in the frame. The more steps that are included in the frame the higher the pitch of sound. A simple procedure gave rise to a musical scale (in eleven steps) which is based on the laws of visual perspective. A range of volume is introduced by varying the exposure. The darker the image the louder the sound (it can be the other way round but Musical Stairs uses a soundtrack made from the negative of the picture). The fact that the staircase is neither a synthetic image, nor a particularly clean one (there happened to be leaves on the stairs when I shot the film) means that the sound is not pure, but dense with strange harmonies.

L’ARRIVÉE

Peter Tscherkassky, Austria, 1998, b/w, sound, 3 min

Just as the record player needle has to find the right groove, “L’Arrive” has to settle into the perforation tracks before the narrative line can develop. A train arrives in a station where a hand-instigated collision with another train takes place. The event is not just a depiction, but a battle of the material itself. This is not the end, but the transition to a kiss, the Happy End. L’Arrive demonstrates where cinema begins – with the spectacular, and where it ends – with intimacy. (Bert Rebhandl)

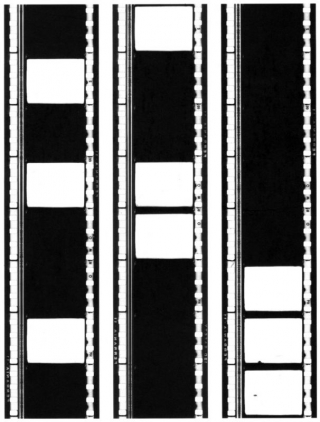

SHUTTER

Taka Iimura, 1971, Japan, b/w, sound, 22 min

Using two projector speeds and various camera speeds, Iimura photographed the light thrown onto a screen by a projector with no film running through it. Because of the disparities between the speeds of the camera and projector shutters, the resulting footage, which he printed first in positive, then in negative, creates a series of flicker effects. One of the more interesting of those many works which have attempted to explore the visual potential of film process and materials. (Scott MacDonald)

Back to top

Date: 18 October 2001 | Season: Cinema Auricular

OHM TAPING: TAPE COMPOSITIONS & MUSIQUE CONCRETE

Thursday 18 October 2001, at 7:30pm

London Barbican Cinema

Before the sampler: the tape machine. Before the break-beat: the tape loop. Before plunderphonics: musique concrete. Going back to a time when it was inventive and original to play with and re-appropriate snatches of sound gathered from disparate sources. Pre post-modernism from pre-eminent filmmakers.

Note: Where the soundtrack is not by the filmmaker, the composer’s name is in square brackets

Malcolm Le Grice, Threshold, 1972, 10 min

Keewatin Dewdney, The Maltese Cross Movement, 1967, 8 min [The Beach Boys]

Carolee Schneemann, Viet Flakes, 1965, 9 min [James Tenney]

John Schofill , Xfilm, 1966-68, 14 min [William Moraldo]

Stan Brakhage, I … Dreaming, 1988, 7 min [Joel Haertling]

Jud Yalkut & Nam Jun Paik, Beatles Electroniques, 1966-69, 3 min [Kenneth Werner]

JJ Murphy, Ice, 1972, 7 min

Ivan Zulueta, Masaje, 1972, 3 min

Jeff Keen, Marvo Movie, 1967, 5 min [Bob Cobbing]

Robert Breer, Fist Fight, 1964, 9 min [Karlheinz Stockhausen]

Eino Ruutsalo, Kaksi Kanaa, 1963, 4 min [Erkki Kurenniemi]

Jud Yalkut, Turn Turn Turn, 1965-66, 10 min [The Byrds]

PROGRAMME NOTES

OHM TAPING: TAPE COMPOSITIONS & MUSIQUE CONCRETE

Thursday 18 October 2001, at 7:30pm

London Barbican Cinema

THRESHOLD

Malcolm Le Grice, UK, 1972, colour, sound, 10 min

Le Grice no longer simply uses the optical printer as a reflexive mechanism, but utilises the possibilities of colour-shift and permutation of imagery as the film progresses from simplicity to complexity. The initial use of pure red and green filters gives way to a broad variety of colours and the introduction of strips of coloured celluloid which are drawn through the printer and begins to build an image which becomes graphically and spatially complex – if still abstract – and which evokes the paintings of, say, Clifford Still or Morris Louis. With the film’s culmination in representational, photographic imagery, one would anticipate a culminating ‘richness’ of image; yet the insistent evidence of splice bars and the loop and repetition of the short piece of found footage and the conflicting superimposition of filtered loops all reiterate the work which is necessary to decipher that cinematic image. (Deke Dusinberre)

THE MALTESE CROSS MOVEMENT

Keewatin Dewdney, Canada, 1967, colour, sound, 8 min [The Beach Boys]

The film reflects Dewdney’s conviction that, “the projector, not the camera, is the filmmaker’s true medium”. The form and content of the film are shown to derive directly from the mechanical operation of the projector – specifically the animation of the disk and the cross illustrates graphically (no pun intended) the projector’s essential parts and movements. It also alludes to a dialectic of continuous-discontinuous movements that pervades the apparatus, from its central mechanical operation to the spectator’s perception of the film’s images … His soundtrack demonstrates that what we hear is also built out of continuous-discontinuous ‘sub-sets’. The film is organised around the principle that it can only complete itself when enough separate and discontinuous sounds have been stored up to provide the male voice on the soundtrack with the sounds needed to repeat a little girl’s poem; “The cross revolves at sunset / The moon returns at dawn / If you die tonight / Tomorrow you’re gone.” (William C. Wees)

VIET FLAKES

Carolee Schneemann, USA, 1965, b/w, sound, 9 min [James Tenney]

Composed from an obsessive collection of Vietnam atrocity images I collected from foreign magazines and newspapers over a five-year period. Magnifying glasses from the ‘five and dime’ were taped onto a borrowed 16mm Bolex in order to physically ‘travel’ within the photographs – producing a rough animation. Images in and out of focus, broken rhythms and pans, the abstracted shapes and motions, speeding perceptual contradictions. For instance, a pointillism of falling black specks in focus becomes bombs dropping through the sky; and impressionistic swirl of tones translates as faces of US soldiers leading barefoot villagers from a gas-filled tunnel; a “Rembrandt ink drawing” focuses in as a tank dragging a roped body… James Tenney’s sound collage intercuts three-second fragments of Vietnamese religious chants and secular songs with fragments of Bach and 1960s ‘Top of the Charts’.

XFILM

John Schofill, USA, 1966-68, colour, sound, 14 min [William Moraldo]

Through precise manipulation of individual frames and groups of frames, Schofill creates an overwhelming sense of momentum practically unequalled in synaesthetic cinema. There is almost a visceral, tactile impact to these images, which plunge across the field of vision like a dynamo. (Gene Youngblood)

I … DREAMING

Stan Brakhage, USA, 1988, colour, sound, 7 min [Joel Haertling]

A setting-to-film of a ‘collage’ of Stephen Foster phrases by composer Joel Haertling. The recurring musical themes and melancholia of Foster refer to ‘loss of love’ in the popular ‘torch song’ mode; but the film envisions a re-awakening of such senses-of-love as children know, and it posits (along a line of words scratched over picture) the psychology of waiting.

BEATLES ELECTRONIQUES

Jud Yalkut & Nam Jun Paik, USA, 1966-69, colour, sound, 3 min [Kenneth Werner]

Shot in black and white from a live broadcast of the Beatles while Paik electromagnetically improvised distortions on the receiver, and also from videotapes material produced during a series of experiments with filming off the monitor of a Sony videotape recorder. The film is three minutes long and is accompanied by an electronic soundtrack by composer Ken Werner, called “Four Loops”, derived from four electronically altered loops of Beatles sound material. The result is an eerie portrait of the Beatles not as pop stars, but rather as entities that exist solely in the world of electronic media. (Gene Youngblood)

ICE

JJ Murphy, USA, 1972, colour, sound, 7 min

To make Ice Murphy projected Franklin Miller’s film Whose Circumference is Nowhere onto one side of a block of ice and recorded what one could see through the ice from the opposite side, in a single continuous take. The soundtrack is a tape recorder recording under water. The result is a transformation of Miller’s film into an abstract experience of a very different kind. (Scott MacDonald)

MASAJE

Ivan Zulueta, Spain, 1972, b/w, sound, 3 min

Using the technique of direct photography off the TV screen, he composes three minutes “in which we see, speeded up, the complete television programming on a day of union and military parades. There was a subliminal Franco, and we didn’t even submit it to the censors…” The soundtrack alternates effects, noises and sounds of all kinds. The result is a really frenetic visual ‘massage’ that exposes the viewer’s eye to fleeting movie images, ads and news reports in rapid-fire succession. (Carlos F. Heredero)

MARVO MOVIE

Jeff Keen, 1967, UK, colour, sound, 5 min [Bob Cobbing]

Movie wizard initiates shatter brain experiment Eeeow! – the fastest movie firm alive – at 24 or 16fps even the mind trembles – splice up sequence two – flix unlimited, an inside yr very head the images explode – last years models new houses and such terrific death scenes while the time and space operator attacks the brain via the optic nerve – will the operation succeed – will the white saint reach in time the staircase now alive with blood – only time will tell says the movie master – meanwhile deep inside the space museum… (Ray Durgnat)

FIST FIGHT

Robert Breer, Fist Fight, USA, 1964, colour, sound 9 min [Karlheinz Stockhausen]

The film articulates separated by sections of blackness. In each burst a technique or series of images may dominate or provide a matrix, but all the elements (photographs, cartoons, abstractions) occur in each cluster. The serial structure is reinforced by the soundtrack. The filmmaker had completed the silent editing for a premiere presentation as part of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s event “Originale”, in New York in 1964. The soundtrack was initially recorded during the performances of the event, including the film’s projection. Breer then composed bursts of audience noise, music, and nearly quiet backgrounds in relationship to the images. (P. Adams Sitney)

KAKSI KANAA

Eino Ruutsalo, Finland 1963, colour, sound, 4 min [Erkki Kurenniemi]

According to Ruutsalo himself, Kaksi kanaa (1963) was composed spontaneously out of throwaway footage. It features a hysterical cavalcade of female nudity, oppressed screen tests, crackers, a floating feather plus an overdose of paint and colour. The soundtrack is a refined electro-acoustical tape collage made by composer Otto Donner. This score, mostly played on Erkki Kurenniemi’s home-built electronic instruments, is a forgotten peak moment of Finnish film music. Kaksi Kanaa is cinematic action painting, and in its condensed expression perhaps Ruutsalo’s most original and permanent masterpiece. (Mika Taanila)

TURN TURN TURN

Jud Yalkut, USA, 1965-66, colour, sound, 10 min [The Byrds]

A film of the eye-shattering, flashing, rotating light sculptures programmed by USCO to turn turn turn the popular song into a rich electronic fugue on the word NOW: Let’s take the OW out of NOW, let’s take the NO out of NOW. (Film Quarterly)

Back to top

Date: 21 October 2001 | Season: Cinema Auricular

LA REGION CENTRALE

Sunday 21 October 2001, at 3:00pm

London Tate Modern

Snow’s mammoth endeavour. Three hours of continuous swooping, swirling, twisting pans over a desolate Canadian landscape. The remote tonal instructions to the camera provoked an inspired minimal (maximal) soundtrack. Hold on to your hats, this trip may take some time.

Michael Snow, La Region Centrale, Canada, 1970-71, colour, sound, 190 min

Special off-site screening related to the “Cinema Auricular” programme at the Barbican Cinema.

Date: 8 November 2001 | Season: London Film Festival 2001 | Tags: London Film Festival, Peter Kubelka, What is Film?

PETER KUBELKA: WHAT IS FILM?

8-14 November 2001

London National Film Theatre

“Peter Kubelka is the perfectionist of the film medium” (Stan Brakhage)

A series of four public lectures in which films from Lumière to the present day will be used to celebrate cinema as a cultural phenomenon, whilst defining film as an independent medium and distinguishing it from those arts that existed before it, and the new media (such as television and the internet) that have become dominant in recent years.

Peter Kubelka will demonstrate the unique and indispensable qualities of film through detailed analysis of those works that best represent the essence of the cinema. In this extraordinary series of events, he will expose the mechanics and grammar of film that are otherwise hidden from the public. After viewing the films, the audience will have an opportunity to look over his shoulder in a situation similar to that of seeing the filmmaker at the editing table. Using a projecting Steenbeck, Kubelka will analyse, letter by letter, the language that cinema speaks. He will argue that as each mode of communication induces its own world-view, the vital and autonomous experience of cinema cannot be transferred to other media without loss of content or the understanding of the artist’s original intentions. Film is a tool that is able to create new thoughts and Peter Kubelka will bring forth the hardcore of cinema: those ideas and concepts that cannot be touched by any other art form.

“Kubelka’s cinema is like a piece of crystal, or some other object of nature: it does not look like it was produced by man.” (P. Adams Sitney)

Peter Kubelka is one of the most distinguished figures in the history of 20th century independent filmmaking. His films, made between 1955 and 1977, are an innovative demonstration of cinematic possibilities and now reside in the collections of many world-renowned museums. Moreover, his practice is not only limited to filmmaking: as an artist or theoretician he has also worked in architecture, literature, music, painting and cooking. During his time as co-director of the Austrian Film Museum in Vienna, which he founded in 1964, he has passionately dedicated himself to other artistic practices. His formation of the ensemble Spatium Musicum led to an intensive study of essential music, and his teaching on the topic of food preparation as an art form at the Frankfurt School of Fine Arts led to an extension of his title as Professor of Film to that of Film and Cooking. His design for an ideal cinema auditorium, The Invisible Cinema, has been realised in New York and Vienna. Over the past 40 years he has lectured at museums, universities and institutions throughout the world, and has been awarded the Austrian State Prize for his life’s work.

(Mark Webber)

PETER KUBELKA: WHAT IS FILM?

1: THE FILMMAKERS VIEW: THE EVENT OF CINEMA

2: THE MATERIAL OF FILM: TOOL AND PERSONALITY

3: THE LANGUAGE OF FILM: METAPHORS BETWEEN SOUNDS AND IMAGES

4: THE REAL WORLD: A MYTH CREATED BY CINEMA

Date: 8 November 2001 | Season: London Film Festival 2001 | Tags: London Film Festival, Peter Kubelka, What is Film?

PETER KUBELKA: WHAT IS FILM? 1

Thursday 8 November 2001, at 6:35pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

THE FILMMAKERS VIEW: THE EVENT OF CINEMA

“Every endeavour to be objective is personal. I begin my analysis of cinema with the analysis of my own work, which contained my position before I was able to put some of it into words.”

Featuring the following works:

Peter Kubelka, Arnulf Rainer, Austria, 1960, 6m

Peter Kubelka, Schwechater, Austria, 1958, 1m

Peter Kubelka, Adebar, Austria, 1957, 1m

Étienne-Jules Marey, La Chronophotographie, France, 1882–1902, photographic slides

The complete list of films in the repertory, and the themes covered, may be subject to spontaneous change during the course of the presentations.

Date: 8 November 2001 | Season: London Film Festival 2001 | Tags: London Film Festival, Peter Kubelka

IN KUBELKA’S SHADOW

Thursday 8 November 2001, at 9pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

A selection of films by former students of the “Film und Kochen” course at the Staatliche Hochschule für Bildende Künste (Städelschule) in Frankfurt. The shadow of Professor Peter Kubelka looms large over these works by his young protégés, as the films are characterised by an acute attention to detail and by the respect paid to each individual frame. Absolute care is taken with composition while cutting together adjacent shots and in the juxtaposition between sound and image. Several of the films are extraordinary travelogues, covering Romania (Palatca, Frühling 1997), Italy (Mia Zia and Il Palio) and Taiwan (Hwa-Shan-District, Taipei), as alive as the spaces they portray. Turning their attention to the body, Zehetner investigates foot fetishism, and Sackl makes a time-lapse documentation of personal activities, an elementary performance. Metropolen des Leichtsinns uses found footage to consider the possibilities of human experience. Biesendorfer’s films are the most tactile; No Wonder is a directly emotional and explicit diary of life and love.

Bernhard Schreiner, Hwa-Shan-District, Taipei, Germany, 2001, 13 min

Nino Pezzella, Mia Zia, Germany, 1992/2000, 2 x 2 min

Gergard Geiger, Palatca, Frühling 1997, Germany, 2000. 23 min

Georg Wasner, Il Palio, ein Film über die gemeinsame Reise nach Italien, Germany, 1999, 2 x 1 min

Gunther Zehetner, Meine Verehrung, Germany, 2000, 9 min

Thomas Draschan & Ulrich Wiesner, Metropolen des Leichtsinns, Germany, 2000, 12 min

Albert Sackl, Gut Ein Tag Mit Verschiedenem, Germany, 2000, 12 min

Frank Biesendorfer, No Wonder, Germany, 1999, 12 min

Many thanks to Thomas Draschan and Peter Kubelka for their assistance with this programme.

Also screening: Saturday 10 November 2001, at 1:30pm, NFT3

Date: 10 November 2001 | Season: London Film Festival 2001 | Tags: London Film Festival, Peter Kubelka, What is Film?

PETER KUBELKA: WHAT IS FILM? 2

Saturday 10 November 2001, at 4:15pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

THE MATERIAL OF FILM: TOOL AND PERSONALITY

“Film is a transparent sculpture. The material is servant and teacher. Form cannot be transferred and therefore content cannot be transferred. The event of Cinema is unique.”

Featuring selections from the following works:

Emile Cohl, Le Cerceau Magique, France, 1908, 6m

Len Lye, Free Radicals, USA, 1958, 4m

Stan Brakhage, Mothlight, USA, 1963, 3m

Owen Land (Formerly Known As George Landow), Film in which there Appear Sprocket Holes, Edge Lettering, Dirt Particles, etc., USA, 1965-66, 5m

Karin Hörler, Frisch, Germany, 1987, 2m

Bruce Conner, Valse Triste, USA, 1979, 6m

Frères Lumière, Voltiges, France, 1898, 1m

Frères Lumière, Indochine, Enfants Anamites, France, 1898, 1m

Frères Lumière, La Course en Sacs, France, 1898, 1m

Stan Brakhage, Window Water Baby Moving, USA, 1962, 12m

Paul Sharits, T:O:U:C:H:I:N:G, USA, 1968, 12m

The complete list of films in the repertory, and the themes covered, may be subject to spontaneous change during the course of the presentations.

Date: 12 November 2001 | Season: London Film Festival 2001 | Tags: London Film Festival, Peter Kubelka, What is Film?

PETER KUBELKA: WHAT IS FILM? 3

Monday 12 November 2001, at 6:30pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

THE LANGUAGE OF FILM: METAPHORS BETWEEN SOUNDS AND IMAGES

“Film articulates in metaphors. Between frames, between frames and contemporaneous sounds, between sounds and other sounds brought together by the maker. I will try to make the atoms of film language audible and visible.”

Featuring selections from the following works:

Fernand Léger, Ballet Mecanique, France, 1923-24, excerpt

Robert Breer, Time Flies, USA, 1997, 5m

Dziga Vertov, Enthusiasm, Russia, 1930, excerpt

Paul Sharits, Word Movie, USA, 1966, 4m

Georges Méliès, Le Magicien, France, 1898, 1m

Peter Kubelka, Unsere Afrikareise, Austria, 1966, 12.5m

The complete list of films in the repertory, and the themes covered, may be subject to spontaneous change during the course of the presentations.

Date: 12 November 2001 | Season: London Film Festival 2001 | Tags: London Film Festival

MODERN MEDITATIONS

Monday 12 November 2001, at 9pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

Amid the constantly accelerated media milieu of the modern word, it is fortunately still possible to discover works that demand quiet contemplation, as demonstrated by this selection of predominantly abstract recent film and video. Myriam Bessette, a member of Montréal new media collective Perte-De-Signal, presents a study of the organic aspect of the electronic signal transmission. Bardo by luminary innovator Jordan Belson draws on imagery from his mesmerising and cosmic films of the past. Acting on his instruction, this new work was edited on digital video by his assistant Ying Tan and continues his life-long journey into the transcendent potential of abstraction. While contemplating the “dictatorship of meaning”, Envers provides further proof of Patrice Kirchofer’s command of photography and processing as glimpses of exquisite images briefly emerge from a body of darkness. By applying simple algorithms to visual noise, Bart Vegter created the “cellular automatons” which provide the basis of Forest-Views. The work oscillates between kaleidoscopic colour modulation and the fragile computer generated ‘chemical’ structures that pervade this remarkable film. Joel Schlemowitz offers an homage to colour, set to a poem by Wanda Phipps. Lovesong furthers Brakhage’s exposition of light. Through step-printing and painted filmstrips, he interweaves elaborate biological forms and representations. The final two films both demonstrate a visible admiration for his work; “Anodyne” is a gentle and timeless, melancholic reading, while Notre Icare creates a more contemporary, dynamic impression using music by Autechre.

Myriam Bessette, Nutation, Canada, 2000, 3 min

Jordan Belson, Bardo, USA, 2000, 20 min

Patrice Kirchhofer, Envers, France, 2001, 20 min

Bart Vegter, Forest-Views, Netherlands, 1999, 14 min

Stan Brakhage, Lovesong, USA, 2001, 7 min

Joel Schlemowitz, Morning Poem #40, USA, 2001, 2 min

Sheri Wills, Anodyne, USA, 2001, 4 min

Johanna Vaude, Notre Icare, France, 2001, 8 min

Also screening: Wednesday 14 November 2001, at 1:30pm, NFT3

Date: 14 November 2001 | Season: London Film Festival 2001 | Tags: London Film Festival, Peter Kubelka, What is Film?

PETER KUBELKA: WHAT IS FILM? 4

Wednesday 14 November 2001, at 6:30pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

THE REAL WORLD: A MYTH CREATED BY CINEMA

“Of the world we know only what art has taught us. In the last 100 years cinema has shaped a world, real for us, of which our ancestors could not have dreamed.”

Featuring selections from the following works:

Marie Menken, Go, Go, Go!, USA, 1962-64, 11m

Robert Breer, Eyewash, USA, 1959, 3m

Michael Snow, See You Later / Au Revoir, Canada, 1990, 16m

Fernand Léger, Ballet Mecanique, France, 1923-24, excerpt

Frères Lumière, Demolition D’un Mur, France, 1896, 1m

Georges Kuchar, Hold Me While I’m Naked, USA, 1966, 15m

Georges Kuchar, Wild Night in El Reno, USA, 1977, 6m

Luis Buñuel & Salvador Dalí, L’age D’or, Spain, 1930, excerpt

The complete list of films in the repertory, and the themes covered, may be subject to spontaneous change during the course of the presentations.