Date: 14 April 2007 | Season: Swingeing London

SWINGEING LONDON: 1

Saturday 14 April 2007, at 9:30pm

Filmhuis Den Haag

TOWERS OPEN FIRE

Antony Balch & William Burroughs, UK, 1963, 16mm, b/w, sound, 16 min

The remarkable Towers Open Fire was conceived by filmmaker and distributor Antony Balch and “Naked Lunch” author William Burroughs, and features appearances by their associates Ian Sommerville, Brion Gysin and Alexander Trocchi. Envisioned as a cinematic realisation of Burroughs’ key themes, such as the breakdown in control, the film contains rapid editing, flicker, strobing and extreme jump cuts that interrupt the narrative flow. A brief passage of hand painted colour was applied to each print (during Mikey Portman’s dance sequence), and the film includes footage of the prototype Dreamachine, designed by Gysin to stimulate the brain’s alpha waves and aid hallucination. The British Censor requested removal of some offensive language from the soundtrack but passed (or failed to notice) the shots of Balch masturbating, and of Burroughs shooting up.

“Society crumbles as the Stock Exchange crashes, members of the Board are raygun-zapped in their own boardroom, and a commando in the orgasm attack leaps through a window and decimates a family photo collection …” (Tony Rayns, Cinema Rising, 1972)

HEADS

Peter Gidal, UK, 1969, 16mm, b/w, silent, 35 min

One of the major filmmakers and theorists of the 1970s, Gidal moved from New York to London in 1968, and his association with Andy Warhol’s Factory brought an air of authenticity to the LFMC. His cool, oppositional stance refuted narrative and representation, denying illusion and manipulation though visual codes, and his films moved towards a persistent denial of the photographic image. Heads is a silent series of tight, claustrophobically cropped portraits of artists, filmmakers, musicians and cultural activists. Some are London residents, others were just passing through. Charlie Watts, Bill West, Jane, John Blake, Linda Thorson, Marsha Hunt, Steve Dwoskin, Thelonious Monk, Peter Townsend, David Hockney, Marianne Faithful, Carol Garney-Lawson, David Gale, Richard Hamilton, Dieter Meier, Rufus Collins, Leslie Smith, Anita Pallenburgh, Claes Oldenburgh, Francis Bacon, Adrian Munsey, Carolee Schneeman, Andrew Garnett-Lawson, Jim Dine, Vivian, Prenai, Winston, Gregory Markopoulos, Rosie, Patrick Procktor and Francis Vaughan.

“Clinical subjectivity, a construct, a consciously, precisely set-up situation. 31 people’s faces: tight closeup (10:1 zoom lens head on stare). Movement happens against the strict construct. The realness is within the framework as set up and defined, a non-illusory use of film structure and film situation.” (Peter Gidal, 1970)

RICHARD HAMILTON

James Scott, UK, 1969, 16mm, colour, sound, 25 min

Richard Hamilton was a new kind of documentary on the arts, made by filmmaker James Scott in complete collaboration with Hamilton himself. Devoid of authoritative voiceover, the film presents samples of the artist’s work alongside reference materials, found footage, scenes from Hollywood features and news reports of the Jagger/Richards/Fraser drugs trial. Bing Crosby, Marilyn Monroe and Patricia Knight (in Sirk and Fuller’s long forgotten Shockproof) also put in appearances as the film traces the inspiration behind some of Hamilton’s signature paintings.

“We have to start with a rather peculiar premise – that I don’t like art films”, says Richard Hamilton at the beginning of this one. Images from the mass media have provided the inspiration for many of his paintings and Scott’s film presents some of this source material and shows how the artist has treated it. Despite its brevity, this brilliant and informative film – as much an extension of Hamilton’s work as a comment on it – is itself constructed as an epic viewing session, with an intermission advertising ice cream and Coca-Cola, a trailer for Desert Hawk with Yvonne De Carlo and, as an entirely appropriate pop art ending, Mr. Universe and Miss World striding off into a golden sky lit by the first rays of dawn.” (Konstantin Bazarov, Monthly Film Bulletin, 1971)

TALK MR BARD

John Latham, UK, 1968, 16mm, colour, sound, 7 min

Talk Mr Bard consists of the crude and rapid animation of a seemingly endless succession of coloured paper discs. The homemade soundtrack is a chaotic college of radio fragments and interference. A tutor at Saint Martins School of Art, Latham organised a dinner party at which he invited friends to chew pages from Clement Greenberg’s book “Art and Culture”, which had been borrowed from the college library. The soggy paper was spat out and fermented in a mixture of sulphuric acid, sodium bicarbonate and yeast. When he eventually received an overdue notice from the library months later, Latham encased the remaining liquid in a glass teardrop, which he labelled “Essence of Greenberg” and returned. He lost his job, but had the last laugh some years later by selling the residue of the event to the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Also screening: Tuesday 17 April 2007, at 8:30pm

Back to top

Date: 15 April 2007 | Season: Swingeing London

SWINGEING LONDON: 2

Sunday 15 April 2007, at 5pm

Filmhuis Den Haag

LOVE LOVE LOVE

Michael Nyman, UK, 1967, 16mm, b/w, sound, 5 min

Hyde Park, 16th July 1967: Thousands attended the Legalise Pot Rally, a love-in to demonstrate the need for a relaxation of England’s strict drug laws. Love Love Love, made by composer Michael Nyman, is a pixillated record of the event with an obligatory Beatles soundtrack. The film features poet Allen Ginsberg, playwright Heathcoate Williams and artist David Medalla (leader of performance group The Exploding Galaxy). The peaceful protest was organised by SOMA (Society of Mental Awareness), who, one week later, placed a full page notice to argue their case in the Times newspaper. The advertisement was paid for by Paul McCartney and signed by 65 luminaries from both the underground and the establishment. Widely assumed to be timed in protest against the recent conviction of Jagger and Richards, the advert was more directly prompted by the swingeing sentence passed on John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins, who received nine months in prison for possession of a small quantity of pot.

WHOLLY COMMUNION

Peter Whitehead, UK, 1965, 16mm, b/w, sound, 33 min

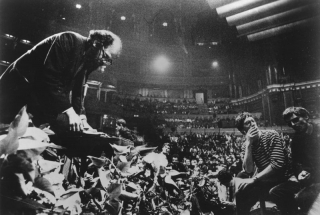

The International Poetry Incarnation at the Royal Albert Hall is regarded as the defining moment that inaugurated London’s sixties adventure. Peter Whitehead’s crisply shot, b/w film, only a half hour long, is remarkably comprehensive in documenting key performances of the evening, and captures the tangible sense of expectation that must have permeated the atmosphere within the cavernous concert hall. Wholly Communion not only encapsulates this seminal moment in which the underground went public, but remains one of the few records of a whole generation of poets performing in their prime.

“The event began with Allen Ginsberg chanting and playing finger cymbals, performing a Hindu mantra which was described by The Times newspaper, as a “heavily amplified incomprehensible song to the accompaniment of a bell-like instrument”. Alexander Trocchi compered the evening, which consisted of four hours worth of readings and performances by Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Harry Fainlight, Adrian Mitchell, Michael Horovitz, Ernst Jandl, Christopher Logue, John Esam, Pete Brown, Anselm Hollo, George Macbeth, Simon Vinkenoog, Paulo Leonni, Daniel Richter, Spike Hawkins, and Tom McGrath, as well as the playing of tapes of, and by, William Burroughs. Poets who, although radically different in style, “showed their hatred of the narrow mind and heart, and joined in celebration of God-as-total-consciousness.” Despite being organized in a matter of days, a press conference announcing the event the previous week guaranteed an estimated audience of 7000 inside the venue, who had been invited to: “Come in fancy dress,” “Come with flowers,” and “Come.”” (Jack Sargeant)

ANATOMY OF VIOLENCE

Peter Davis, UK, 1967, 16mm, b/w, sound, 30 min (shown on video)

The symposium on the Dialectics of Liberation and the Demystification of Violence, organised by R.D. Laing, experimental psychologist and author of “The Divided Self”, was structured like an academic conference with invited speakers, panel discussions and open meetings. Over 15 days at the Camden Roundhouse it covered subjects such as Black Power, Vietnam, personal liberty and the freedom of speech. Key lectures were released by the Institute of Phenomenological Studies on a series of 23 LP records. Anatomy of Violence features proclamations by Allen Ginsberg, Herbert Marcuse, Stokely Carmichael and Emmett Grogan, and a discussion group including Carolee Schneeman and auto-destructive artist Gustav Metzger. Filmmaker Peter Davis later won an Academy Award for Hearts and Minds, his 1974 documentary on the Vietnam War.

REIGN OF THE VAMPIRE

Malcolm Le Grice, UK, 1970, 16mm b/w, sound, 15 min

Le Grice’s work developed through direct processing, printing and projection, gaining an understanding of the material and exploring duration while touching on aspects of spectacle and narrative, and using early computer imagery. Reign of the Vampire addresses contemporary paranoia about the military-industrial complex, the Vietnam War, and the suspected influence of American government’s intelligence agency in countercultural activities. It was the last of a group of works shown together under the collective title “How to Screw the CIA, or How to Screw the CIA ?”

“This film could be considered as a synthesis of the series. It is formally based on the permutative loop structure, superimposing a series of three pairs of image loops of different lengths with each other. The images include elements from all the previous parts of the series. The film sequences that make up the loops are chosen for their combination of semantic relationships, and abstract factors of movement. The soundtrack is constructed for the film, but independently, and has a similar loop structure.” (Malcolm Le Grice)

Also Screening: Wednesday 18 April 2007, at 8:30pm

Back to top

Date: 15 April 2007 | Season: Swingeing London

SWINGEING LONDON: 3

Sunday 15 April 2007, at 9:30pm

Filmhuis Den Haag

MARE’S TAIL

David Larcher, UK, 1969, 16mm, colour, sound, 143 min

An extended, personal journey which, through an accumulation of visual information, builds into a treatise on the experience of seeing. Its loose, indefinable structure explores new possibilities for perception and narrative. Reinforcing the idea of the mythopoeic discourse and the historically romantic view of the artist-filmmaker, Mare’s Tail is a legend, consisting of layers of sounds and images that reveal each other over an extended period. It’s a personal vision, an aggregation of experience, memories and moments overlaid with indecipherable intonations and altered musics. The collected footage is extensively manipulated, through refilming, superimposition or chemical treatment. The film does not demand constant attention: the viewer may slip in and out as it runs its course, though persistence is rewarded by experience after the full projection has been endured.

“Mare’s Tail is an epic flight into inner space. It is a two-and-a-half-hour visual accumulation in colour, the filmmaker’s personal odyssey, which becomes the odyssey of each of us. It is a man’s life transposed into a visual realm, a realm of spirits and demons, which unravel as mystical totalities until reality fragments. Every movement begins a journey. There are spots before your eyes, as when you look at the sun that flames and burns. We look at distant moving forms and flash through them. We drift through suns; a piece of earth phases over the moon. A face, your face, his face, a face that looks and splits into shapes that form new shapes that we rediscover as tiny monolithic monuments. A profile as a full face. The moon again, the flesh, the child, the room and the waves become part of a hieroglyphic language … Mare’s Tail is an important film because it expresses life. It follows Paul Klee’s idea that a visually expressive piece adds ‘more spirit to the seen’ and also ‘makes secret visions visible’. Like other serious films and works of art, it keeps on seeking and seeing, as the filmmaker does, as the artist does. It follows the transience of life and nature, studying things closely, moving into vast space, coming in close again. The course it follows is profoundly real and profoundly personal: Larcher’s trip becomes our trip to experience. It cannot be watched impatiently, with expectation; it is no good looking for generalization, condensation, complication or implication.” (Stephen Dwoskin, Film Is, 1975)

Also Screening: Thursday 19 April 2007, at 8:30pm

Back to top

Date: 25 April 2007 | Season: Swingeing London

SWINGEING LONDON: THE SIXTIES UNDERGROUND

A Touring Programme from Filmhuis Den Haag

Wednesday 25 April 2007, Utrecht ‘t Hoogt

Sunday 29 April 2007, Rotterdam Lantaren/Venster

Tuesday 8—Wednesday 9 May 2007, Amsterdam Filmmuseum

Monday 14 May 2007, Arnhem Filmhuis

Soon after the Beatles first shook England out of the Dark Ages, it seemed like “Swinging London” was the place to be. The cultural Renaissance that had begun in the late 1950s, with the Free Cinema movement and British Pop Art, exploded across the nation and for a few years it seemed that anything was possible. Under the surface of the mainstream, an underground counterculture challenged the conventions of music, literature, art and filmmaking.

This programme shows how the influence of American Beat culture prompted British experimentation with media, ranging from the appearance of William Burroughs in Towers Open Fire to an unseen psychedelic happening inside the BBC TV studios. The films date from a time when artists created a new language of looking, and include music by Soft Machine, the Beatles and the Troggs.

Antony Balch & William Burroughs, Towers Open Fire, UK, 1963, 16 min

Michael Nyman, Love Love Love, UK, 1967, 5 min

Boyle Family, Poem for Hoppy, UK, 1967, 4 min

John Hopkins / TVX, Videospace Reel, UK, 1970, 15 min

Stephen Dwoskin, Naissant, UK, 1964-67, 14 min

John Latham, Talk Mr Bard, UK, 1968, 7 min

Simon Hartog, Soul in a White Room, UK, 1968, 3 min

Malcolm Le Grice, Reign of the Vampire, UK, 1970, 15 min

SWINGEING LONDON is curated by Mark Webber and takes its title from Richard Hamilton’s series of prints depicting Mick Jagger and Robert Fraser on their way to court, where they were convicted for the possession of illegal substances.

PROGRAMME NOTES

SWINGEING LONDON: THE SIXTIES UNDERGROUND

A Touring Programme from Filmhuis Den Haag

TOWERS OPEN FIRE

Antony Balch & William Burroughs, UK, 1963, 16mm, b/w, sound, 16 min

The remarkable Towers Open Fire was conceived by filmmaker and exploitation film distributor Antony Balch and “Naked Lunch” author William Burroughs, and features appearances by their associates Ian Sommerville, Brion Gysin and Alexander Trocchi. Envisioned as a cinematic realisation of Burroughs’ key themes, such as the breakdown in control, the film contains rapid editing, flicker, strobing and extreme jump cuts that interrupt the narrative flow. A brief passage of hand painted colour was applied to each print (during Mikey Portman’s dance sequence), and the film includes footage of the prototype Dreamachine, designed by Gysin to stimulate the brain’s alpha waves and aid hallucination. The British Censor requested removal of some offensive language from the soundtrack but passed (or failed to notice) the shots of Balch masturbating, and of Burroughs shooting up.

“Society crumbles as the Stock Exchange crashes, members of the Board are raygun-zapped in their own boardroom, and a commando in the orgasm attack leaps through a window and decimates a family photo collection …” (Tony Rayns, Cinema Rising, 1972)

LOVE LOVE LOVE

Michael Nyman, UK, 1967, 16mm, b/w, sound, 5 min

Hyde Park, 16th July 1967: Thousands attended the Legalise Pot Rally, a love-in to demonstrate the need for a relaxation of England’s strict drug laws. Love Love Love, made by composer Michael Nyman, is a pixillated record of the event with an obligatory Beatles soundtrack. The film features poet Allen Ginsberg, playwright Heathcoate Williams and artist David Medalla (leader of performance group The Exploding Galaxy). The peaceful protest was organised by SOMA (Society of Mental Awareness), who, one week later, placed a full page notice to argue their case in the Times newspaper. The advertisement was paid for by Paul McCartney and signed by 65 luminaries from both the underground and the establishment. Widely assumed to be timed in protest against the recent conviction of Jagger and Richards, the advert was more directly prompted by the swingeing sentence passed on John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins, who received nine months in prison for possession of a small quantity of pot.

POEM FOR HOPPY

Boyle Family, UK, 1967, 16mm, colour, sound, 4 min (shown on video)

An improvised performance, by Soft Machine and the Sensual Laboratory, in protest against John Hopkins’ conviction for marijuana possession.

“Mark Boyle and Joan Hills lived in and around Ladbroke Grove in the middle 1960s, organising events and making sculptures that attempted to present reality as it is. The events included various projection pieces presenting physical and chemical change: boiling water, burning slides and bodily fluids that led to them being asked by Hoppy to do a presentation at the first night of the UFO club, where their liquid light of exploding colours became the main visual accompaniment to the bands that performed there. Pink Floyd, Soft Machine, Jimi Hendrix, the underground scene and psychedelic lightshows exploded out of UFO, across London and around the world.” (Portobello Film Festival)

VIDEOSPACE REEL

John Hopkins / TVX, UK, 1970, 16mm, colour, sound, 15 min (shown on video)

This recently rediscovered reel of early video image processing by John Hopkins and the TVX collective begins with a music “visualisation” made for the BBC to accompany the track “Scotland” by Area Code 615. The remaining footage is an excerpt from the Videospace happening which took place inside a BBC TV studio: an un-broadcast optical dub session which incorporated music, tape, film and feedback loops, lightshows, dancing, inflatables and live video mixing.

NAISSANT

Stephen Dwoskin, UK, 1964-67, 16mm, b/w, sound, 14 min

Dwoskin’s early films were heavily influenced by Warhol, in both the visual content and extended duration. They typically consisted of long takes from a fixed or hand-held camera, with an attractive young woman as the only protagonist. Composer Gavin Bryars provided the soundtrack to Naissant and several others.

“Objective location: a bed; subjective location: in thoughts. Being with thoughts and the child to be born. Camera from three sides of the bed with three lenses working from bed level and standing level. Filmed in New York in 1964, completed in London 1967. Naissant presents being alone with one’s thoughts. Time and her inner thoughts are found out only by spending time with her in the film.” (Stephen Dwoskin)

TALK MR BARD

John Latham, UK, 1968, 16mm, colour, sound, 7 min

Talk Mr Bard consists of the crude and rapid animation of a seemingly endless succession of coloured paper discs. The homemade soundtrack is a chaotic college of radio fragments and interference. A tutor at Saint Martins School of Art, Latham organised the protest Still and Chew in August 1966, for which he invited friends to chew pages from Clement Greenberg’s book “Art and Culture”, which had been borrowed from the college library. The soggy paper was spat out and fermented in a mixture of sulphuric acid, sodium bicarbonate and yeast. When he eventually received an overdue notice from the library months later, Latham encased the remaining liquid in a glass teardrop, which he labelled “Essence of Greenberg” and returned. He lost his job, but had the last laugh some years later by selling the residue of the event to the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

SOUL IN A WHITE ROOM

Simon Hartog, UK, 1968, 16mm, colour, sound, 3 min

LFMC founder member Simon Hartog was one of the most politically aware filmmakers of the period. This early short film is an amusing piece of social commentary on mixed race relationships, which were hardly commonplace in the UK at that time, and has a soundtrack by The Troggs. The male character played by Omar Dop-Blondin, a Sengelese student fresh from the Paris 68 protests, and an associate of the London Black Panthers.

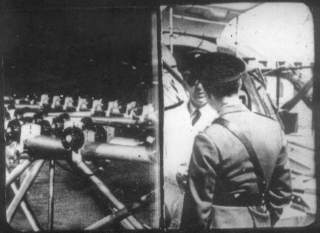

REIGN OF THE VAMPIRE

Malcolm Le Grice, UK, 1970, 16mm, b/w, sound, 15 min

Le Grice’s work developed through direct processing, printing and projection, gaining an understanding of the material and exploring duration while touching on aspects of spectacle and narrative, and using early computer imagery. Reign of the Vampire addresses contemporary paranoia about the military-industrial complex, the Vietnam War, and the suspected influence of American government’s intelligence agency in countercultural activities. It was the last of a group of works shown together under the collective title “How to Screw the CIA, or How to Screw the CIA ?”

“This film could be considered as a synthesis of the series. It is formally based on the permutative loop structure, superimposing a series of three pairs of image loops of different lengths with each other. The images include elements from all the previous parts of the series. The film sequences that make up the loops are chosen for their combination of semantic relationships, and abstract factors of movement. The soundtrack is constructed for the film, but independently, and has a similar loop structure.” (Malcolm Le Grice)

Back to top

Date: 23 May 2007 | Season: Shoot Shoot Shoot 2006 | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT: EXPANDED CINEMA

Wednesday 23 May 2007, at 7PM

Wrexham Arts Centre

Beginning in the 1960s, artists at the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative experimented with multiple projection, live performance and film environments. In liberating cinema from traditional theatrical presentation, they broke down the barrier between screen and audience, and extended the creative act to the moment of exhibition. “Shoot Shoot Shoot” presents historic works of Expanded Cinema, for which each screening is a unique, collective experience, in stark contrast to contemporary video installations. In Line Describing a Cone, a film projected through smoke, light becomes an apparently solid, sculptural presence, whilst other works for multiple projection create dynamic relationships between images and sounds.

Malcolm Le Grice, Castle Two, 1968, b/w, sound, 32 min (2 screens)

Sally Potter, Play, 1971, b/w & colour, silent, 7 min (2 screens)

William Raban, Diagonal, 1973, colour, sound, 6 min (3 screens)

Gill Eatherley, Hand Grenade, 1971, colour, sound, 8 min (3 screens)

Lis Rhodes, Light Music, 1975-77, b/w, sound, 20 min (2 screens)

Anthony McCall, Line Describing A Cone, 1973, b/w, silent, 30 min. (1 screen, smoke)

Curated by Mark Webber. Presented in association with LUX.

PROGRAMME NOTES

SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT: EXPANDED CINEMA

Wednesday 23 May 2007, at 7PM

Wrexham Arts Centre

EXPANDED CINEMA at the LONDON FILM-MAKERS’ CO-OPERATIVE

Expanded Cinema is a term used to describe works that do not confirm to the traditional single-screen cinema format. It could mean having two (or more) images side-by-side on the screen, films that incorporate live performances or are projected in an unorthodox manner without a screen. Even light pieces that do not use any film at all. Some work demands that the filmmaker interact with the projected image, or be behind the projectors to alter their configuration throughout the screening.

The London Film-Makers’ Co-operative was an artist-led organisation formed in 1966, and uniquely incorporated a distribution office, workshop laboratory and screening room. Expanded Cinema continued the analytical exploration of the material that was conducted by filmmakers in the workshop, and emphasised the transient nature of the medium.

The Co-op’s cinema space was a flat, open room with no fixed seating. Filmmakers were free to experiment with projectors, demonstrating that the moment of exhibition can be as much a part of the work as the original concept, filming, editing and processing. The technology that puts the illusion of movement onscreen was no longer hidden away in a projection booth behind the audience, but placed amongst them.

In questioning the role of the spectator, Expanded Cinema challenged the conventions of the cinema event and introduced elements of chance and improvisation. Sometimes, what happened across the room was more important than what was up on the screen. With such work no two projections were ever the same: each screening was a unique, social, collective experience for the assembled audience.

This drive beyond the screen and theatre inevitably took the work into galleries, but only as a practical measure since open spaces and white walls were ideal for unconventional projection. The filmmakers made no attempts to commodify their work by producing editions, for many it was against their socialist principles. Though Expanded Cinema anticipated many recent trends in gallery-based moving image works and installations, there was little acceptance from the art world in the early years, or acknowledgement of this groundbreaking work today.

Mark Webber

CASTLE TWO

Malcolm Le Grice, 1968, b/w, sound, 32 min (2 screens)

“This film continues the theme of the military/industrial complex and its psychological impact upon the individual that I began with Castle One. Like Castle One, much use is made of newsreel montage, although with entirely different material. The film is more evidently thematic, but still relies on formal devices – building up to a fast barrage of images (the two screens further split – to give 4 separate images at once for one sequence). The images repeat themselves in different sequential relationships and certain key images emerge both in the soundtrack and the visual. The alienation of the viewer’s involvement does not occur as often in this film as in Castle One, but the concern with the viewer’s experience of his present location still determines the structure of certain passages in the film.” —Malcolm Le Grice, London Film-Makers’ Co-operative catalogue, 1968

“Le Grice’s work induces the observer to participate by making him reflect critically not only on the formal properties of film but also on the complex ways in which he perceives that film within the limitations of the environment of its projection and the limitations created by his own past experience. A useful formulation of how this sort of feedback occurs is contained in the notion of ‘perceptual thresholds’. Briefly, a perceptual threshold is demarcation point between what is consciously and what is pre-consciously perceived. The threshold at which one is able to become conscious of external stimuli is a variable that depends on the speed with which the information is being projected, the emotional charge it contains and the general context within which that information is presented. This explains Le Grice’s continuing use of devices such as subliminal flicker and the looped repetition of sequences in a staggered series of changing relationships.” —John Du Cane, Time Out, 1977

PLAY

Sally Potter, 1971, b/w & colour, silent, 7 min (2 screens)

“In Play, Potter filmed six children – actually, three pairs of twins – as they play on a sidewalk, using two cameras mounted so that they recorded two contiguous spaces of the sidewalk. When Play is screened, two projectors present the two images side by side, recreating the original sidewalk space, but, of course, with the interruption of the right frame line of the left image and the left frame line of the right image – that is, so that the sidewalk space is divided into two filmic spaces. The cinematic division of the original space is emphasized by the fact that the left image was filmed in color, the right image in black and white. Indeed, the division is so obvious that when the children suddenly move from one space to the other, ‘through’ the frame lines, their originally continuous movement is transformed into cinematic magic.” —Scott MacDonald, A Critical Cinema 3, 1998)

“To be frank, I always felt like a loner, an outsider. I never felt part of a community of filmmakers. I was often the only female, or one of few, which didn’t help. I didn’t have a buddy thing going, which most of the men did. They also had rather different concerns, more hard-edged structural concerns … I was probably more eclectic in my taste than many of the English structural filmmakers, who took an absolute prescriptive position on film. Most of them had gone to Oxford or Cambridge or some other university and were terribly theoretical. I left school at fifteen. I was more the hand-on artist and less the academic. The overriding memory of those early years is of making things on the kitchen table by myself…” —Sally Potter interviewed by Scott MacDonald, A Critical Cinema 3, 1998

DIAGONAL

William Raban, 1973, colour, sound, 6 min (3 screens)

“Diagonal is a film for three projectors, though the diagonally arranged projector beams need not be contained within a single flat screen area. This film works well in a conventional film theatre when the top left screen spills over the ceiling and the bottom right projects down over the audience. It is the same image on all three projectors, a double-exposed flickering rectangle of the projector gate sliding diagonally into and out of frame. Focus is on the projector shutter, hence the flicker. This film is ‘about’ the projector gate, the plane where the film frame is caught by the projected light beam.” —William Raban, Perspectives on British Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1977

“The first great excitement is finding the idea, making its acquaintance, and courting it through the elaborate ritual of film production. The second excitement is the moment of projection when the film becomes real and can be shared with the audience. The former enjoyment is unique and privileged; the second is not, and so long as the film exists, it is infinitely repeatable.” —William Raban, Arts Council Film-Makers on Tour catalogue, 1980

HAND GRENADE

Gill Eatherley, 1971, colour, sound, 8 min (3 screens)

“Although the word ‘expanded’ cinema has also been used for the open/gallery size/multi screen presentation of film, this ‘expansion’ (could still but) has not yet proved satisfactory – for my own work anyway. Whether you are dealing with a single postcard size screen or six ten-foot screens, the problems are basically the same – to try to establish a more positively dialectical relationship with the audience. I am concerned (like many others) with this balance between the audience and the film – and the noetic problems involved.” —Gill Eatherley, 2nd International Avant-Garde Film Festival programme notes, 1973

“Malcolm Le Grice helped me with Hand Grenade. First of all I did these stills, the chairs traced with light. And then I wanted it to all move, to be in motion, so we started to use 16mm. We shot only a hundred feet on black and white. It took ages, actually, because it’s frame by frame. We shot it in pitch dark, and then we took it to the Co-op and spent ages printing it all out on the printer there. This is how I first got involved with the Co-op.” —Gill Eatherley, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

LIGHT MUSIC

Lis Rhodes, 1975-77, b/w, sound, 20 min (2 screens)

“Lis Rhodes has conducted a thorough investigation into the relationship between the shapes and rhythms of lines and their tonality when printed as sound. Her work Light Music is in a series of ‘moveable sections’. The film does not have a rigid pattern of sequences, and the final length is variable, within one-hour duration. The imagery is restricted to lines of horizontal bars across the screen: there is variety in the spacing (frequency), their thickness (amplitude), and their colour and density (tone). One section was filmed from a video monitor that produced line patterns on the screen that varied according to sound signals generated by an oscillator; so initially it is the sound which produces the image. Taking this filmed material to the printing stage, the same lines that produced the picture are printed onto the optical soundtrack edge of the film: the picture thus produces the sound. Other material was shot from a rostrum camera filming black and white grids, and here again at the printing stage, the picture is printed onto the film soundtrack. Sometimes the picture ‘zooms’ in on the grid, so that you actually ‘hear’ the zoom, or more precisely, you hear an aural equivalent to the screen image. This equivalence cannot be perfect, because the soundtrack reproduces the frame lines that you don’t see, and the film passes at even speed over the projector sound scanner, but intermittently through the picture gate. Lis Rhodes avoids rigid scoring procedures for scripting her films. This work may be experienced (and was perhaps conceived) as having a musical form, but the process of composition depends on various chance operations, and upon the intervention of the filmmaker upon the film and film machinery. This is consistent with the presentation where the film does not crystallize into one finished form. This is a strong work, possessing infinite variety within a tightly controlled framework.” —William Raban, Perspectives on British Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1977

“The film is not complete as a totality; it could well be different and still achieve its purpose of exploring the possibilities of optical sound. It is as much about sound as it is about image; their relationship is necessarily dependent as the optical sound track ‘makes’ the music. It is the machinery itself which imposes this relationship. The image throughout is composed of straight lines. It need not have been.” —Lis Rhodes, A Perspective on English Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1978

LINE DESCRIBING A CONE

Anthony McCall, 1973, b/w, silent, 30 min (1 screen, smoke)

“Once I started really working with film and feeling I was making films, making works of media, it seemed to me a completely natural thing to come back and back and back, to come more away from a pro-filmic event and into the process of filmmaking itself. And at the time it all boiled down to some very simple questions. In my case, and perhaps in others, the question being something like “What would a film be if it was only a film?” Carolee Schneemann and I sailed on the SS Canberra from Southampton to New York in January 1973, and when we embarked, all I had was that question. When I disembarked I already had the plan for Line Describing a Cone fully-fledged in my notebook. You could say it was a mid-Atlantic film! It’s been the story of my life ever since, of course, where I’m located, where my interests are, that business of “Am I English or am I American?” So that was when I conceived Line Describing a Cone and then I made it in the months that followed.” —Anthony McCall, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

“One important strategy of expanded cinema radically alters the spatial discreteness of the audience vis-à-vis the screen and the projector by manipulating the projection facilities in a manner which elevates their role to that of the performance itself, subordinating or eliminating the role of the artist as performer. The films of Anthony McCall are the best illustration of this tendency. In Line Describing a Cone, the conventional primacy of the screen is completely abandoned in favour of the primacy of the projection event. According to McCall, a screen is not even mandatory: The audience is expected to move up and down, in and out of the beam – this film cannot be fully experienced by a stationary spectator. This means that the film demands a multi-perspectival viewing situation, as opposed to the single-image/single-perspective format of conventional films or the multi-image/single-perspective format of much expanded cinema. The shift of image as a function of shift of perspective is the operative principle of the film. External content is eliminated, and the entire film consists of the controlled line of light emanating from the projector; the act of appreciating the film – i.e., ‘the process of its realisation’ – is the content.” —Deke Dusinberre, “On Expanding Cinema”, Studio International, November/December 1975

Back to top

Date: 26 May 2007 | Season: Evolution 2007 | Tags: Aldo Tambellini, Evolution

ALDO TAMBELLINI: ELECTROMEDIA & THE BLACK FILM SERIES

Saturday 26 May 2007, at 3pm

Leeds Opera North Linacre Studio

As a key figure of the 1960s Lower East Side arts scene, Aldo Tambellini used a variety of media for social and political communication. In the age of McLuhan and Fuller, Tambellini manipulated new technology in an exploration of the “psychological re-orientation of man in the space age.” He presented immersive, multi-media environments and, having made his first experimental video as early as 1966, participated in early collaborations between artists and broadcast television.

His dynamic Black Film Series (1965-69) extends from total abstraction to footage of the assassination of Bobby Kennedy, the Vietnam War, and black teenagers in Coney Island. Tambellini worked directly on the film strip with chemicals, paint and ink, scratching, scraping, and intercutting material from industrial films, newsreels and TV. Abrasive, provocative and turbulent, the series is a rapid-fire response to the beginning of the information age and a world in flux. “Black to me is like a beginning … Black is within totality, the oneness of all. Black is the expansion of consciousness in all directions.”

“Electromedia was the fusion of the various art and media – breaking media away from it’s ‘traditional media role’ – bringing it into the area of modern art – bringing the others arts – poetry – sounds – painting – kinetic sculpture – into a time/space reorientation toward media – transforming both the arts and the media …” (Aldo Tambellini)

Aldo Tambellini will be present to introduce and discuss his early work in film and video.

Programme curated by Mark Webber for Evolution 2007. Programme repeated at Lucca Film Festival 30 September 2007.

PROGRAMME NOTES

ALDO TAMBELLINI: ELECTROMEDIA & THE BLACK FILM SERIES

Saturday 26 May 2007, at 3pm

Leeds Opera North Linacre Studio

A true intermedia activist, Aldo Tambellini was a key figure of the Lower East Side arts scene, working in sculpture, painting, poetry, film, video and theatre. Believing it was “no longer sufficient for the creative individual to remain in isolation,” he co-founded the alternative arts community Group Center in 1960. After publishing counterculture newsletters and making early happenings to protest against the art establishment (such as presenting The Golden Screw Award to the Museum of Modern Art), Tambellini embraced new technology as a tool to explore the “psychological re-orientation of man in the space age.”

His first ‘electromedia event’ BLACK (1965) fused painting, music, poetry and dance with projected ‘lumigrams’ (hand-painted glass slides) in an immersive environment. The idea of ‘black’ as a spatial and psychological concept dominated Tambellini’s work for many years. “Black to me is like a beginning … Black is within totality, the oneness of all. Black is the expansion of consciousness in all directions.”

The Black Film Series, a sequence of seven films made between 1965-69, is a primitive, sensory exploration of the medium, which ranges from total abstraction to the assassination of Bobby Kennedy, the Vietnam War, and black teenagers in Coney Island. Before picking up a camera, Tambellini physically worked on the film strip, treating the emulsion with chemicals, paint, ink and stencils, slicing and scraping the celluloid, and dynamically intercutting material from industrial films, newsreels and broadcast television. Abrasive, provocative and turbulent, the series is a rapid-fire response to the beginning of the information age and a world in flux.

In 1966, Tambellini purchased the first Sony video recorder and made an experimental tape by shining a light directly into the camera lens, burning out the photoconductive vidicon tube. This monochrome tape was broadcast by ABC Television in 1967. Black Video Two – spontaneously improvised from test signals whilst the first tape was being duplicated – was later colourized using the Paik-Abe Video Synthesizer at WNET (1973) to create 6673.

One of the first artists to explore television as a means of personal expression, Tambellini collaborated with Otto Piene on Black Gate Cologne, an hour-long multi-media happening broadcast by WDR in January 1969, and contributed to The Medium is the Medium at WGBH Boston, alongside Nam June Paik and Allan Kaprow (also 1969). That same year, under commission from the Howard Wise Gallery, Tambellini worked with Bell Laboratories engineers to create Black Spiral, a manipulated television set, for the groundbreaking exhibition “TV as a Creative Medium”.

During his tenure at the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the 1970s and 1980s, Tambellini established Communicationsphere, connecting artists with technicians and engineers to “dissolve the boundaries between media, the arts and life.” Most recently he has returned to writing and performing poetry, and made the award-winning digital video poem Listen (2005) in collaboration with Anthony Tenczar.

Reaching beyond its application as an aesthetic tool, Tambellini has consistently used media as a means of social and political communication, often working in collaboration with others to investigate the creative potential of electronics and technology.

BLACK FILM SERIES

“Tambellini is one of the pioneers of lntermedia. His Black series in film and intermedia is obsessed with Black. His Black is like a ‘blind spot’ – a phantasy with the speed of nightmare. Hypnotic effect of organic microscopic forms. From darkness of the daemon to brightness to sperm to womb to friction contraction expansion. It is a trip for blind America.” Takahiko Iimura, Eiga Hyoron (Japanese Film Review)

BLACK IS

Aldo Tambellini, 1965, 16mm, b/w, sound, 4 min

seed black

seed black

sperm black

sperm black

a film made entirely without the use of the camera

(Aldo Tambellini)

BLACK TRIP #1

Aldo Tambellini, 1965, 16mm, b/w, sound, 5 min

Black Trip #1 is pure abstraction after the manner of a Jackson Pollock. Through the uses of kinescope, video, multimedia, and direct painting on film, an impression is gained of the frantic action of protoplasm under a microscope where an imaginative viewer may see the genesis of it all. (Grove Press Film Catalog)

BLACK TRIP #2

Aldo Tambellini, 1967, 16mm, b/w, sound, 3 min

“An internal probing of the violence and mystery of the American psyche seen through the eye of a black man and the Russian revolution.” (Aldo Tambellini)

BLACKOUT

Aldo Tambellini, 1965, 16mm, b/w, sound, 9 min

This film, like an action painting by Franz Kline, is a rising crescendo of abstract images. Rapid cuts of white forms on a black background supplemented by an equally abstract soundtrack give the impression of a bombardment in celestial space or on a battlefield where cannons fire on an unseen enemy into the night. (Grove Press Film Catalog)

BLACK PLUS X

Aldo Tambellini, 1966, 16mm, b/w, sound, 9 min

Tambellini here focuses on contemporary life in a black community. The extra, the “X” of Black Plus X, is a filmic device by which a black person is instantaneously turned white by the mere projection of the negative image. The time is summer, and the place is an oceanside amusement park where black children are playing in the surf and enjoying the rides, quite oblivious to Tambellini’s tongue?in?cheek “solution” to the race problem. (Grove Press Film Catalog)

BLACK TV

Aldo Tambellini, 1968, 16mm, b/w, sound, 10 min

The film is an artist’s sensory perception of the violence of the world we live in, projected through a television tube. Tambellini presents it subliminally in rapid?fire abstractions in which such horrors as Robert Kennedy’s assassination, murder, infanticide, prize fights, police brutality at Chicago, and the war in Vietnam are out?of?focus impressions of faces and events.” (Grove Press Film Catalog)

ABC-TV INTERVIEW

Aldo Tambellini, 1967, video, b/w, sound, 3 min

This interview with Aldo Tambellini was shot on 21st December 1967, at the Black Gate Theatre, for an ABC Television series on the New York Lower East Side Arts Scene. It includes an excerpt from Black Video One, his first experimental videotape, which had been made the previous year by shining a light directly into the camera lens, burning out the photoconductive vidicon tube.

BLACK (EXCERPT FROM THE MEDIUM IS THE MEDIUM)

Aldo Tambellini, 1969, video, b/w, sound, c.6 min

“In 1969 [Tambellini] was one of six artists participating in the PBL programme “The Medium Is the Medium” at WGBH-TV in Boston. The videotape produced for the project, called Black, involved one thousand slides, seven 16mm film projections, thirty black children, and three live TV cameras that taped the interplay of sound and image. The black-and-white tape is extremely dense in kinetic and synaesthetic information, assaulting the senses in a subliminal barrage of sight and sound events. The slides and films were projected on and around the children in the studio, creating an overwhelming sense of the black man’s life in contemporary America. Images from all three cameras were superimposed on one tape, resulting in a multidimensional presentation of an ethnological attitude. There was a strong sense of furious energy, both Tambellini’s and the blacks’, communicated through the space/time manipulations of the medium.” (Gene Youngbood, Expanded Cinema)

SCREENING ON A MONITOR IN THE FOYER

6673

Aldo Tambellini, 1966-73, video, colour, sound, 55 min (looped)

6673 is based on Tambellini’s second tape, Black Video 2, which dates from 1966. It was created at the Video Flight dubbing house by manipulating test patterns and other electronic signals. The soundtrack combines audio produced by an oscilloscope (which also distorted the images) with Tambellini’s wordless, vocal improvisation. In 1973, Tambellini added colour and further manipulated the original material using the Paik-Abe Synthesiser at WNET’s artists’ television lab in New York.

Back to top

Date: 18 September 2007 | Season: ZXZW 2007

CINEMA FOR THE EYES AND EARS

ZXZW Festival at Tilburg FilmFoyer

Tuesday 18 September 2007, at 9pm

The potential for combining image and sound has been explored since the invention of cinema. This primer of classic works of the international avant-garde demonstrates some of the possibilities specific to the film medium, from the flickering frames of Tony Conrad, Paul Sharits and John Latham to the intricate optics of Daina Krumins, Malcolm Le Grice, and others. Featuring soundtracks by Brian Eno, Rhys Chatham, John Cale and Terry Riley. All films will be shown on 16mm.

Peter Kubelka, Arnulf Rainer, Austria, 1958, 8 min

Wojciech Bruszewski, YYAA, Poland, 1973, 5 min

John Latham, Speak, UK, 1968-69, 11 min

Malcolm Le Grice, Berlin Horse, UK, 1970, 8 min

Daina Krumins, The Divine Miracle, USA, 1973, 5 min

Paul Sharits, Axiomatic Granularity, USA, 1972-73, 20 min

Lis Rhodes, Dresden Dynamo, UK, 1974, 5 min

Tony & Beverly Conrad, Straight and Narow, USA, 1970, 11 min

The programme also screened in The Wire 25 season at London Roxy Bar and Screen on Tuesday 30 October 2007, at 8pm.

PROGRAMME NOTES

CINEMA FOR THE EYES AND EARS

ZXZW Festival at Tilburg FilmFoyer

Tuesday 18 September 2007, at 9pm

ARNULF RAINER

Peter Kubelka, Austria, 1958, 35mm, b/w, sound, 8 min

“He has even created a film whose images can no more be ‘turned off’ by the closing of eyes than can the soundtrack thereof it (for it is composed entirely of white frames rhythming thru black inter-spaces and of such an intensity as to create its pattern straight thru closed eyelids) so that the whole ‘mix’ of the audio-visual experience is clearly ‘in the head’, so to speak: and if one looks at it openly, one can see ones own eye cells as if projected onto the screen and can watch one’s optic physiology activated by the soundtrack in what is, surely, the most basic Dance of Life of all (for the sounds of the film do resemble and, thus, prompt the inner ear’s hearing of its own pulse output at intake of sound).” (Stan Brakhage)

YYAA

Wojciech Bruszewski, Poland, 1973, 35mm, colour, sound, 5 min

“The author of the film (appearing on the screen) is shouting “YAAAH…” The light comes from four sources being switched at random (this takes between 1 and 8 seconds) by an electronic device. In any moment, only one of the four lamps casts light on the filmmaker. Each light-change is accompanied by a different voice modulation of the author’s voice. The film technique makes it possible for the author to exhale for several minutes. The alternating close-ups and half-close-ups are totally unjustified.” (Wojciech Bruszewski)

SPEAK

John Latham, UK, 1968-69, 16mm, colour, sound, 11 min

“Speak is his second attack on the cinema. Not since Len Lye’s films in the thirties has England produced such a brilliant example of animated abstraction. Speak burns its way directly into the brain. It is one of the few films about which it can truly be said, ‘it will live in your mind’.” (Ray Durgnat)

BERLIN HORSE

Malcolm Le Grice, UK, 1970, 16mm, colour, sound, 8 min

“Berlin Horse is a synthesis of a number of works which explore the transformation of the image by re-filming from the screen and by complex printing techniques. There are two original sequences: a piece of early newsreel and a section of 8mm film shot in Berlin – a village in Northern Germany. The 8mm material is re-filmed in various ways from the screen onto 16mm and that in turn used for permutative superimposition and color treatment in the printer. The music is composed for the film by Brian Eno and like elements of the image, explores off-setting loops with each other so that their phases shift.” (Malcolm Le Grice)

THE DIVINE MIRACLE

Daina Krumins, USA, 1973, 16mm, colour, sound, 5 min

“An intriguing composite of what looks like animation and pageant-like live action is The Divine Miracle, which treads a delicate line between reverence and spoof as it briefly portrays the agony, death and ascension of Christ in the vividly coloured and heavily outlined style of Catholic devotional postcards, while tiny angels (consisting only of heads and wings) circle like slow mosquitoes about the central figure. Ms. Krumins tells me that no animation is involved, that the entire action was filmed in a studio, and that Christ, the angels and the background were combined in the printing. She also says it took her two years to produce it.” (Edgar Daniels)

AXIOMATIC GRANULARITY

Paul Sharits, USA, 1972-73, 16mm, colour, sound, 20 min

“In Spring 1972 a series of analyses of colour emulsion ‘grain’ imagery was undertaken (the word ‘imagery: is significant because only representations of light sensitive crystals, or ‘grain’, remain on a developed roll of colour film). The investigation is preliminary to the shooting of Section 1 of “Re: Re: Projection”, Variable Emulsion Density, wherein attempts to construct convincing lap dissolves of solid colour fields with straight fine grain Ektachrome ECO proved unsatisfactory. It was thought that more ‘grainy’ colour field interactions might adequately prevent the undesirable smoothness of hue mixture resulting from ECO superimposition. A discreteness of individual hues, during superimposition, is necessary; then, a switch to Ektachrome EF, pushed extra stops in development, seemed somewhat reasonable. Still, unexpected (colour blurring) problems arose and it was clear that a ‘blow up’ of the situation was called for; a set of primary principles was needed and, particle by particle, Axiomatic Granularity seemed to formulate itself. Its ‘structure’ lacks normative ‘expressive intentionality’.” (Paul Sharits)

DRESDEN DYNAMO

Lis Rhodes, UK, 1974, 16mm, colour, sound, 5 min

“The result of experiments with the application of Letraset and Letratone onto clear film. It is essentially about how graphic images create their own sound by extending into that area of film which is ‘read’ by optical sound equipment. The final print has been achieved through three separate, consecutive printings from the original material, on a contact printer. Colour was added with filters on the final run. The film is not a sequential piece. It does not develop crescendos. It creates the illusion of spatial depth from essentially flat, graphic, raw material.” (Tim Bruce)

STRAIGHT AND NARROW

Tony & Beverly Conrad, USA, 1970, 16mm, b/w, sound, 11 min

“An extension of the flicker film phenomenon, Straight and Narrow is a study in subjective colour and visual rhythm. Although it is printed on black and white film, the hypnotic pacing of the images will cause viewers to experience a programmed gamut of hallucinatory colour effects. Straight And Narrow uses the flicker phenomenon not as an end in itself, but as an effectuator of other related phenomena. In this film the colours which are so illusory in The Flicker are visible and under the programmed control of the filmmaker. Also, by using images which alternate in a vibrating flickering schedule, a new impression of motion and texture is created.” (Film-Makers’ Cooperative catalogue)

Back to top

Date: 19 September 2007 | Season: ZXZW 2007

LA RÉGION CENTRALE

ZXZW Festival at Tilburg FilmFoyer

Wednesday 19 September 2007, at 8pm

La Région Centrale is arguably the most spectacular experimental film made anywhere in the world, and for John W. Locke, writing in Artforum in 1973, it was “as fine and important a film as I have ever seen.” If ever the term “metaphor on vision” needed to be applied to a film it should be to this one. […] For this project he enlisted the help of Pierre Abaloos to design and build a machine which would allow the camera to move smoothly about a number of different axes at various speeds, while supported by a short column, where the lens of the camera could pass within inches of the ground and zoom into the infinity of the sky. Snow placed his device on a peak near Sept Îsles in Quebec’s région centrale and programmed it to provide a series of continuously changing views of the landscape. Initially, the camera pans through 360° passes which map out the terrain, and then it begins to provide progressively stranger views (on its side, upside down) through circular and back-and-forth motions. The weird soundtrack was constructed from the electronic sounds of the programmed controls which are sometimes in synch with the changing framing on screen and sometimes not. (Peter Rist)

Michael Snow, La Région Centrale, Canada, 1971, 180 minutes

PROGRAMME NOTES

LA RÉGION CENTRALE

ZXZW Festival at Tilburg FilmFoyer

Tuesday 19 September 2007, at 9pm

LA RÉGION CENTRALE

Michael Snow, Canada, 1971, 16mm, colour, sound, 180 minutes

La Région Centrale was made during five days of shooting on a deserted mountain top in Northern Quebec. During the shooting, the vertical and horizontal alignment as well as the tracking speed were all determined by the camera’s settings. Anchored to a tripod, the camera turned a complete 360 degrees, craned itself skyward, and circled in all directions. Because of the unconventional camera movement, the result was more than merely a film that documented the film location’s landscape. Surpassing that, this became a film expressing as its themes the cosmic relationships of space and time. Catalogued here were the raw images of a mountain existence, plunged (at that time) in its distance from civilization, embedded in cosmic cycles of light and darkness, warmth and cold. (Martina Sauerwald)

This new, three hour film by the Canadian Michael Snow is an extraordinary cinematic monument. No physical action, not even the presence of man, a fabulous game with nature and machine which puts into question our perceptions, our mental habits, and in many respects renders moribund existing cinema: the latest Fellini, Kubrick, Buñuel etc. For La Région Centrale, Snow had a special camera apparatus constructed by a technician in Montreal, an apparatus capable of moving in all directions: horizontally, vertically, laterally or in a spiral. The film is one continuous movement across space, intercutting occasionally the X serving as a point of reference and permitting one to take hold of stable reality. Snow has chosen to film a deserted region, without the least trace of human life, 100 miles to the north of Sept-Isles in the province of Quebec: a sort of plateau without trees, opening onto a vast circular prospect of the surrounding mountains. In the first frames, the camera disengages itself slowly from the ground in a circular movement. Progressively, the space fragments, vision inverts in every sense, light everywhere dissolves appearance. We become insensible accomplices to a sort of cosmic movement. A sound track, rigorously synchronized, composed from the original sound which programmed the camera, supplies a permanent counterpoint. Michael Snow pushes toward the absurd the essential nature of this ‘seventh’ art which is endlessly repeated as being above the visual. He catapults us into the heart of a world before speech, before arbitrarily composed meanings, even subject. He forces us to rethink not only cinema, but our universe. (Louis Marcorelles, Le Monde, 1972)

Back to top

Date: 25 October 2007 | Season: London Film Festival 2007 | Tags: London Film Festival

THE TIMES BFI 51st LONDON FILM FESTIVAL

Thursday 25 – Sunday 28 October 2007

London BFI Southbank

The Festival’s annual celebration of artists’ film and video returns on 27-28 October 2007 with an international programme of diverse and inventive work. For the first time, Experimenta will also occupy BFI Southbank’s new Studio over the weekend to present continuous installations of digital videos by Ken Jacobs and Rachel Reupke.

This year’s programme ranges from poetic journeys to unfamiliar locations to works which question aspects of specific histories. Whilst video remains the most accessible medium for independent artists, many are choosing again to work with film, either for its visual qualities or physical attributes. It’s ironic, or perhaps inevitable, that this revival of interest comes at a time when the future of celluloid seems to be constantly under threat. The selection includes several works in which artists have worked directly on the filmstrip to create striking and original imagery.

Carolee Schneemann did exactly that for her seminal film Fuses, made forty years ago and presented here in an astounding new preservation print. Marina Abramovic, another eminent and challenging artist, is featured in a hypotonic document of her Guggenheim Museum performance series.

Guest filmmaker David Gatten will lead a practical workshop on the use of text and the moving image, and we are pleased to welcome Peter Hutton to present his stunning new film At Sea.

Other artists featured in the weekend programme include Robert Beavers, Su Friedrich, Bruce Conner, Elodie Pong, Christoph Draeger, Jayne Parker, Steve Reinke, Emily Wardill, Michael Robinson, Mara Mattuschka, and Carl E. Brown. Many will be present appear to introduce and discuss their work over the two-day event. Many other artists will appear to introduce and discuss their work over the two-day event.

The ‘avant-garde weekend’ continues to be a unique occasion for London audiences to experience innovative new visions from around the world.

Other festival highlights for 2007 include the documentaries Black White + Gray: Portrait of Sam Wagstaff and Robert Mapplethorpe and A Walk Into The Sea: Danny Williams and the Warhol Factory (plus a programme of Danny Williams’ Factory Films), Guy Maddin’s Brand Upon the Brain!, and Casting A Glance, James Benning’s film of Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty.

Date: 25 October 2007 | Season: London Film Festival 2007 | Tags: London Film Festival

DAVID GATTEN: THE IMAGE & THE WORD (WORKSHOP)

Thursday 25 October 2007, from 10am-5pm

London BFI Southbank

Festival guest David Gatten leads a practical workshop on the use of text in 16mm filmmaking.

DAVID GATTEN: THE IMAGE & THE WORD (WORKSHOP)

Throughout the history of cinema, images and text have been combined on-screen in a variety of ways and for a range of reasons. Silent-era comedy, mid-century newsreels, avant-garde films and home movies have used words to tell stories, convey facts and explore the enjoyments and anxieties of reading. In this day-long workshop, Brooklyn artist David Gatten will provide an overview of such practice, with particular attention to filmmakers who have deployed on-screen text to investigate the way text functions as both image and language, the border between the legible and illegible, and the limits of what can be known through words.

David Gatten has made prominent use of the printed word in the ongoing series The Secret History of the Dividing Line (sections screened at the LFF in previous years) and his recent Film for Invisible Ink, Case No: 71: Base-Plus-Fog (showing in the Festival on 28 October 2007). Following introductory screenings of relevant works, participants will make their own films using a variety of processes, including direct-on-film applications, ink-and-cellophane tape transfers, slide projections, close-up cinematography, in-camera contact printing and more.

The workshop is suitable for both beginners and experienced practitioners.

Presented in association with no.w.here.

Back to top