Date: 30 October 2004 | Season: London Film Festival 2004 | Tags: London Film Festival

POETRY AND TRUTH

Saturday 30 October 2004, at 9pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

Larry Jordan, Enid’s Idyll, USA, 2004, 17 min

An animated imagining of Arthurian romance based on Gustav Doré’s engraved illustrations for Tennyson’s ‘Idylls of the Kings’, accompanied by the music of Mahler’s ‘Resurrection Symphony’.

Julie Murray, I Began To Wish, USA, 2003, 5 min

Mysterious events unfold in a potting shed … A jewel of found footage, mysterious and profound beyond its imagery, and with an almost deafening aural presence, despite its lack of soundtrack.

Rebecca Meyers, Things We Want To See, USA, 2004, 7 min

An introspective work that obliquely measures the fragility of life against boundless forces of nature, such as Alaskan ice floes, the Aurora Borealis and magnetic storms.

Peter Kubelka, Dichtung Und Wahrheit, Austria, 2003, 13 min

In cinema, as in anthropological study, the ready-made can reveal some of the fundamental ‘poetry and truth’ of our lives. Kubelka has unearthed sequences of discarded takes from advertising and presents them, almost untouched, as documents that unwittingly offer valuable and humorous insights into the human condition.

Morgan Fisher, ( ), USA, 2003, 21 min

‘I wanted to make a film out of nothing but inserts, or shots that were close enough to being inserts, as a way of making them visible, to release them from their self-effacing performance of drudge-work, to free them from their servitude to story.’ (Morgan Fisher)

Ichiro Sueoka, T:O:U:C:H:O:F:E:V:I:L, Japan, 2003, 5 min

Like Fisher’s film, Sueoka’s video also uses cutaways, but this time the shots are from 60s spy dramas, and retain their soundtracks. Stroboscopically cut together, it becomes a strange brew, like mixing The Man from U.N.C.L.E with Paul Sharits’ T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G.

Bruce Conner, Luke, USA, 2004, 22 min

In 1967 Bruce Conner visited Dennis Hopper, Paul Newman and others on the set of Cool Hand Luke and shot a rarely seen roll of silent 8mm film of the production. Almost forty years later, he has returned to this footage and presents it at three frames per second, creating an almost elegiac record of that time. Patrick Gleeson, Conner’s collaborator on several previous films, has prepared an original soundtrack for this new work.

PROGRAMME NOTES

POETRY AND TRUTH

Saturday 30 October 2004, at 9pm

London BFI Southbank NFT3

ENID’S IDYLL

Larry Jordan, USA, 2004, 16mm, b/w, sound, 17 min

I have used 46 engraved Doré illustrations to “Idylls of the King” as settings for his extravagantly romantic saga. As Enid, the protagonist, is seen in a vast array of scenes from deep forests to castle keeps, her champion is sometimes with her, sometimes away fighting archetypal foes. She dies and, through the magic of Gustav Mahler’s resurrection symphony, lives again. (Larry Jordan)

I BEGAN TO WISH

Julie Murray, USA, 2003, 16mm, colour, silent, 5 min

The sea sucks the seed back into the ocean, the flowers fold like umbrellas, shoots recoil into hiding, in seeds that shrink. The plants accelerate their tremble and wobble and glass unbreaks all around them. Strawberries blanch and tomatoes grow pale. The father, leering, holds forth a flower and suddenly his smile fades to awful seriousness. In an odd concentrated ritual the father and son carefully tip over all the flower pots, laying the plants to rest and it is in this end, around the time he figures the flowers are talking to him, that the son wishes his father had killed him. (Julie Murray)

THINGS WE WANT TO SEE

Rebecca Meyers, USA, 2004, 16mm, colour, sound, 7 min

A visit to a place they had seen many times, but wouldn’t again. Just before we left, the northern lights, which she tells me she had always wanted to see (waking in the early hours and waiting), hinted in the sky. Months after she was gone, I heard this recording for the first time. (Rebecca Meyers)

DICHTUNG UND WAHRHEIT

Peter Kubelka, Austria, 2003, 35mm, colour, silent, 13 min

Poetry and Truth was originally presented, albeit in a different format, during one of the “What Is Film” lectures at the Austrian Film Museum in Vienna, in this case on the subject of ‘acting and being’. In addition to screening a behind the scenes reel filmed on the set of The Misfits, Kubelka showed 13-minutes of footage shot by unidentified cameramen for a number of TV commercials made by an Austrian production company. Given that his one-minute masterpiece, Schwechater (1958), began life as a commission for a beer commercial, it would appear that his imagination had once again been aroused by the phantom world of advertising. While assembling the footage for demonstration purposes, the filmmaker succumbed to the impulse to also make the images speak with their own strange and beautiful logic. It would be misleading to call Poetry and Truth a ‘found’ film. Its footage has been gathered, selected, and edited together at very specific junctures to produce an archival, pedagogical, and yet weirdly electrifying collection of ethnographic camera ‘views’. But instead of recording an unknown tribe’s way of life in the wilderness, this ethnography bears witness to certain of our own Western rituals – namely “make believe,” “you should own,” and “go and buy.” Following his ‘metric’ and ‘metaphoric’ film phases, the latter exemplified by Unsere Afrikareise (1966), Kubelka now submits a new type of cinema for our consideration: the ‘metaphysical’ film. Metaphysical in the sense that, for the first time in his career, Kubelka allows the medium’s materiality (i.e., what film physically consists of) to recede, and instead foregrounds cinema’s magical capacity to locate and record anthropological rules, rituals, and myths in the unlikeliest of places. Poetry and Truth features twelve such ‘stories’; twelve sequences, each composed of one shot that is repeated in three, or five, or a dozen variations. Each take captures a movement from a stasis to motion and back again. For Kubelka, the repetition of physical movement – as in dance, as in film, as in life – is the fundamental law of the universe, from which even civilisation’s most complex systems derive. The act of conveying this principle via the ‘truth’ (the camera originals) of commercials is certainly a form of ‘poetry’ – but that’s not the source of the film’s title. At some point in each of these takes, the divine light of illusion falls upon people, dogs, buckets, and pasta. These simple truths’ are abruptly transformed into actors of ‘poetry’, and then, just as suddenly, fall back into their original non-poetic selves. As archaeologist and archivist, Kubelka is dutifully passing these telling artefacts on to the researchers of future generations. It’s easy to see why Kubelka doesn’t want Poetry and Truth to be thought of as a critique of advertising. He’s after something more essential and isn’t interested in using his work to express trivial opinions about some aspect of modern life. He’d rather champion the joy of rhythm, the joy of life, and affirm the cyclical nature of human endeavour – even if it means affirming and preserving the remnants of a trivial economy in the process. (Alexander Horwath, Film Comment)

( )

Morgan Fisher, USA, 2003, 16mm, colour, silent, 21 min

The origin of ( ) was my fascination with inserts. Inserts are a crucial kind of shot in the syntax of narrative films. Inserts show newspaper headlines, letters, and similar sorts of significant details that have to be included for the sake of clarity in telling the story. I have long been struck by a quality of inserts that can be called the alien, and as well the alienated. Narrative films depend on inserts (it’s a very rare film that has none), but at the same time they are utterly marginal. Inserts are far from the traffic in faces and bodies that are the heart of narrative films. Inserts have the power of the indispensable, but in the register of bathos. Inserts are above all instrumental. They have a job to do, and they do it; and they do little, if anything, else. Sometimes inserts are remarkably beautiful, but this beauty is usually hard to see because the only thing that registers is the news, the expository information, that the insert conveys. That’s the unhappy ideal of the insert: you see only what it does, and not what it is. This of course is no more than the ideal of all the instruments of narrative filmmaking and the rules that govern their use. A rule, or a method, underlies ( ), and I have obeyed it, even if the rule and my obedience to it are not visible. I needed the rule to make the film; it is not necessary for you to know what it is. A rule has the power of prediction, but only if you see it. To the extent that the rule remains invisible, the unfolding of the film is, for better or worse, difficult to foresee. The important thing is what the rule does. No two shots from the same film appear in succession. Every cut is a cut to another film. There is interweaving, but it is not the interweaving of dramatic construction, where intention and counter-intention are composed in relation to each other to produce friction that culminates in a climax. Instead it is an interweaving according to a rule that assigns the shots as I found them to their places in an order. In keeping with my wish to locate ( ) as far as possible from the usual conventions of cutting, whether those of montage or those of story films, the rule that puts the shots in the order has nothing to do with what is happening in them. I wanted to free the inserts from their stories, I wanted them to have as much autonomy as they could. I thought that discontinuity, cutting from one film to another, was the best way to do this. It is narrative that creates the need for an insert, assigns an insert to its place and keeps it there. The less the sense of narrative, the greater the freedom each insert would have. But of course any succession of shots, no matter how disparate, brings into play the principles of montage. That cannot be helped. Where there is juxtaposition we assume specific intention and so look for meaning. Even if there is no specific intention, and here there is none, we still look for meaning, some way of understanding the juxtapositions. At each cut I intended only discontinuity, cutting from one film to another, but beyond that nothing more. Indeed, beyond that simple device I could not intend any specific meaning, because whatever happens at each cut is the consequence of whatever two shots the rule put together, and the rule does not know what is in the shots. So what happens specifically at each cut is a matter of chance. (Morgan Fisher)

T:O:U:C:H:O:F:E:V:I:L

Ichiro Sueoka, Japan, 2003, video, colour, sound, 5 min

This is part of the “Requiem for Avant-Garde Film” series. (An example of minimal film for re-reading of Structural Films.) The concept of this work was combined with Paul Sharits’ film, T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G (1968) and the cliché of the Hollywood cinema, especially, crime suspense thrillers. And the title was extracted from Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1957). We could often see the depiction of a close-up hand in cinema, and we may find out that hand was a criminal’s hand. And a flicker was used to signify a crime. That is to say, in a cinema, a hand and flicker are the codes that make the representation of ‘evil’. (Ichiro Sueoka)

LUKE

Bruce Conner, USA, 2004, video, colour, sound, 22 min

Luke is a poetic film document created entirely by Bruce Conner in 1967 during one day of the production of Cool Hand Luke on location near Stockton, California on a country road. The main subject of the film is the Cool Hand Luke production apparatus and the people working behind the camera. The scene being photographed for their movie is a sequence with about 15 shirtless convicts working at the side of a hot black tar road with shovels. Sand is tossed on the road until it is covered. Then they move farther down the road. Shotgun carrying guards oversee their work at all times. The set itself has a representation of military and police officers as well as a highway motorcycle policeman. The actors (Paul Newman, Dennis Hopper, Harry Dean Stanton, George Kennedy etc.) are seen in front and behind the camera that is shooting the movie. The event becomes a stop and go parade since the entire crew and equipment must also be moved down the road to continue filming the continuity of dialogue and action. The final shot is a view of the actors moving their shovels as if they are tossing the sand on the road but the shovels are empty. The original running time for the regular 8mm film would be about 2.5 minutes. The final digital edit of the film to tape transfer in 2004 (with original music by Patrick Gleeson) is longer because each picture frame last one third of a second: there are 3 images per second. It has the character of both a motion picture and a series of still photos. The filming with the hand-held camera created immediate edits in the camera with regular 8mm speed (18 frames per second) as well as one frame at a time. (Bruce Conner)

Back to top

Date: 31 October 2004 | Season: London Film Festival 2004 | Tags: London Film Festival

LOS ANGELES PLAYS ITSELF

Sunday 31 October 2004, at 12pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

Thom Andersen, Los Angeles Plays Itself, USA, 2003, 169 min

A remarkable documentary about cinema, an endlessly fascinating visual lecture and an important social commentary, Thom Andersen’s love letter to Los Angeles explores the city’s representation on film. With its relentless, mesmerising montage of clips and archive footage, the film explores how the Western centre of the film industry is actually portrayed on-screen. Divided into chapters that treat Los Angeles as – amongst other things – background, character and subject, the film revisits crucial landmarks (the steps up which Laurel & Hardy attempted to manoeuvre a piano in The Music Box, explores famous buildings (the Spanish Revival house in Double Indemnity, the cavernous Bradbury Building made famous by Blade Runner), and charts the city’s ‘secret’ history through such films as Chinatown, L.A. Confidential and Who Framed Roger Rabbit. As comfortable with softcore exploitation as it is with the avant-garde, Los Angeles Plays Itself is a cinematic treasure trove that makes one think again about a city that – as a movie location – has never seemed quite as romantic or exciting as New York. Indeed, the world around you may seem more mysterious and compelling after almost three hours well spent in Andersen’s company. And you’ll definitely never refer to Los Angeles as ‘L.A.’ again. (David Cox)

Also Screening: Thursday 28 October 2004, at 8:15pm London NFT1

PROGRAMME NOTES

LOS ANGELES PLAYS ITSELF

Sunday 31 October 2004, at 12pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

LOS ANGELES PLAYS ITSELF

Thom Andersen, USA, 2003, video, colour, sound, 169 min

Most movies are intended to transform documentary into fiction; Thom Andersen’s heady and provocative Los Angeles Plays Itself has the opposite agenda. This nearly three-hour “city symphony in reverse” analyses the way that Los Angeles has been represented in the movies.

Andersen, who teaches at Cal Arts, is the author of two previous, highly original film-historical documentaries – Eadweard Muybridge, Zoopraxographer and Red Hollywood (made with theoretician Noël Burch). A manifesto as well as a monument, Los Angeles Plays Itself has its origins in a clip lecture that Andersen originally “intended for locals only,” but as finished, it is an essay in film form with near-universal interest and a remarkable degree of synthesis. If Andersen’s dense montage and noirish, world-weary voice-over owe a bit to Mark Rappaport’s VCRchaeological digs, his methodology recalls the literary chapters in Mike Davis’s Los Angeles books City of Quartz and Ecology of Fear; no less than Pat O’Neill in The Decay of Fiction, but in a completely different fashion, he has found a way to turn Hollywood history to his own ends.

Digressive if not quite free-associational in his narrative, Andersen begins by detailing the effect that Hollywood has had on the world’s most photographed city – a metropolis where motels or McDonald’s might be constructed to serve as sets and “a place can become a historic landmark because it was once a movie location.” Andersen is steeped in Los Angeles architecture as well as motion pictures, and his thinking is habitually dialectical – the Spanish Revival house in Double Indemnity, which Andersen admires, turns up as another sort of signifier in L.A. Confidential, the movie that inspired his critique (not least because Andersen has the same irritated disdain for the nickname “L.A.” that San Franciscans have for “Frisco”).

With a complex nostalgia for the old Los Angeles and a far-ranging knowledge of its indigenous cinema, Andersen draws on avant-garde and exploitation films as well as studio products. In his first section, “The City as Background,” he wonders why the city’s modern architecture is typically associated with gangsters. (Producers may actually live in these houses, but, as is often the case in Hollywood, “conventional ideology trumps personal conviction.”) Andersen ponders the guilty pleasure of destroying Los Angeles, but he’s most fond of those “literalist” films that preserve, however inadvertently, or at least recognise the city’s geography: Kiss Me Deadly (with its extensive shooting in lost Bunker Hill) and Rebel Without a Cause (in which locations are shot as though they were studio sets).

Andersen goes on to discuss Los Angeles as a “character,” beginning with the city’s transformation, by hard-boiled novelists Raymond Chandler and James M. Cain, into “the world capital of adultery and murder.” The movie’s latter half is devoted to Los Angeles as subject, starting with the self-conscious urban legend of Chinatown and considering other movies – Who Framed Roger Rabbit, L. A. Confidential – that provide the city’s imaginary secret history. A disquisition on the on-screen evolution of Los Angeles cops in the 1990s leads Andersen to the African American filmmakers Charles Burnett and Billy Woodberry, who, in their neo-neorealism, provide the antithesis of movie mystification and studio fakery.

(Jim Hoberman, Village Voice)

Back to top

Date: 31 October 2004 | Season: London Film Festival 2004 | Tags: London Film Festival

NATHANIEL DORSKY: DEVOTIONAL CINEMA

Sunday 31 October 2004, at 4pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

A LECTURE SCREENING

As an antidote to the frenetic pace and complexity of modern life, Nathaniel Dorsky’s films invite an audience to connect at a precious level of intimacy, nourishing both mind and spirit. His camera is drawn towards those transient moments of wonder that often pass unnoticed in daily life: jewelled refractions of sunlight on water, dappled shadows cast along the ground.

The films are photographed, non-narrative and have none of the visual trickery we might associate with the avant-garde. Dorsky’s work achieves a sensitive balance between humanity, nature and the ethereal, weaving together lyrical statements in a rhythmic cadence that creates space for private reflection. The world floods through the lens, onto the screen and into our minds.

In this lecture-screening of Variations (which provided the inspiration for the ‘most beautiful image’ sequence of American Beauty) and his new film Threnody, Dorsky discusses the qualities of cinema that attracted him to use the medium in such a poetic way, and will read from his recently published book ‘Devotional Cinema’. This is his first public appearance in the UK.

Nathaniel Dorsky, Variations, USA, 1992-98, 24 min

Nathaniel Dorsky, Threnody, USA, 2004, 20 min

PROGRAMME NOTES

NATHANIEL DORSKY: DEVOTIONAL CINEMA

As an antidote to the frenetic pace and complexity of modern life, Nathaniel Dorsky’s films invite an audience to connect at a precious level of intimacy, nourishing the mind and spirit. With films assembled in an almost selfless way, the viewer is given the freedom to express oneself more fully, rather than be consciously absorbed in the projections of another person. ‘In these films the audience is the central character and, hopefully, the screen your best friend.’

The films are photographed, non-narrative and have none of the visual trickery we might associate with the ‘avant-garde’. Dorsky’s camera is drawn towards those transient moments of wonder that often pass unnoticed in daily life: the jewelled refraction of sunlight on water, reflections from windows and dappled shadows cast along the ground. His iridescent cinematography is arranged in carefully montaged phrases that remain entirely open to the viewer’s personal interpretation; no heavily coded meanings and subtexts are imposed through associations in the editing. The world floods through the lens, onto the screen and into our minds.

Dorsky approaches each film as though it is a song, weaving together lyrical statements in a rhythmic cadence. His work achieves a sensitive balance between humanity, nature and the ethereal, creating space for private reflection. To accompany this screening of Variations and his new film Threnody, Nathaniel Dorsky will discuss the aspects of cinema that attracted him to use the medium in such a poetic way, to explore the inexpressible qualities of human life, and read from his recently published book ‘Devotional Cinema’. Though his work has been screened at major international museums, festivals and cinematheques, this is his first public appearance in the UK.

Nathaniel Dorsky lives in San Francisco, where he makes a living as a professional ‘film doctor’, editing documentaries that often appear on American public television and the festival circuit. In 1967 he won an Emmy award for his photographic work on the CBS production ‘Gaugin in Tahiti: Search for Paradise’. He has been making personal films since 1964, and his works are in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art (New York), Pacific Film Archives (Berkeley), Image Forum (Tokyo) and Centre Georges Pompidou (Paris). It is widely acknowledged that the ‘most beautiful image’ sequence – a plastic bag floating in the wind – from the Oscar winning feature American Beauty was directly inspired by a similar shot from Dorsky’s film Variations.

(Mark Webber)

VARIATIONS

Nathaniel Dorsky, USA, 1992-98, 16mm, colour, silent, 24 min

‘What tender chaos, what current of luminous rhymes might cinema reveal unbridled from the daytime word? During the Bronze Age a variety of sanctuaries were built for curative purposes. One of the principal activities was transformative sleep. This montage speaks to that tradition.’ (Nathaniel Dorsky)

THRENODY

Nathaniel Dorsky, USA, 2004, 16mm, colour, silent, 20 min

‘Threnody is the second of two devotional songs, the first being The Visitation. It is an offering to a friend who has died.’ (Nathaniel Dorsky)

Back to top

Date: 31 October 2004 | Season: London Film Festival 2004 | Tags: London Film Festival

THROW YOUR WATCH TO THE WATER

Sunday 31 October 2004, at 7pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

Eugeni Bonet, Tira Tu Reloj al Agua (Throw Your Watch to the Water), Spain, 2004, 91 min

José Val del Omar (1904-82), one of the pioneers of European avant-garde film, remains virtually unknown outside of Spain. His visionary Triptico Elemental de España (1953-61) embodies the soul, landscape and diverse cultural mix of his Andalucian homeland, connecting life on our planet with the elementary forces of the universe. Using material shot by the film-maker between 1968-82, Eugeni Bonet has assembled Throw Your Watch to the Water, whose images, ranging from documentary to complete abstraction, mark the passage from the earthly world to a transcendental plane. The film opens in the Alhambra, detailing the intricate Moorish architecture, pulsing fountains and activities of the local people. The ancient citadel, at first serene and regal, is overrun by the transparent bodies of tourists, whilst the ‘videoterrorifico mirror’ of television reflects the frenzy of modern media. Val del Omar envisaged a ‘cinematic vibration’ that would be the vertex of his life’s work, and this film, in which images and thoughts flow free of time, is a meta-mystical allegory that seeks a unity between the spiritual realm, the ancient world and contemporary life.

Also Screening: Saturday 30 October 2004, at 8:30pm, London ICA2

PROGRAMME NOTES

THROW YOUR WATCH TO THE WATER

Sunday 31 October 2004, at 7pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

TIRA TU RELOJ AL AGUA (THROW YOUR WATCH TO THE WATER)

Eugeni Bonet, Spain, 2004, 35mm, colour, sound, 91 min

Despite a circle of admirers that includes the directors Chris Marker and Victor Erice, José Val del Omar (1904-1982), one of the pioneers of European avant-garde film, remains virtually unknown. In pursuing his dream for a cinema for all the senses he made numerous technical innovations and discoveries, and patented designs for cinematic surround sound, wide-screen projection and special lenses years before they became commonplace.

His career began in the 1920s with dozens of ethnographic films made for the Misiones Pedagógicas. Focusing on the impoverished regions of Spain, the surviving examples are reminiscent of the stark, early documentaries of Luis Buñuel.

Throughout the 1950s he worked on the Triptico Elemental de España, consisting of three short 35mm films that each characterised one of the elements: water (Aguaespejo granadino, 1953-55), fire (Fuego en Castilla, 1958-60) and earth (Acariño galaico, 1961). Val del Omar was fundamentally connected to the soul, landscape and culture of his Andalucian homeland, and these films embody its diverse cultural history, referencing Christian and Islamic beliefs, and the connections between life on our planet and the universal whole. There are some similarities with the trance films of Anger, Brahage, Deren and Markopoulos, though Val del Omar’s methods are overtly mystical and cosmic. Throw Your Watch to the Water has been assembled by Eugeni Bonet, working with the Archivo María José Val del Omar and Gonzalo Sáenz de Buruaga, to realise a work that occupied the film-maker for decades up until his sudden death in a car accident.

The film is set in Granada, an extraordinary location where east meets west. It opens with footage of the Alhambra and its surroundings, detailing the extraordinary Moorish architecture and intricate decoration, the pulsing water of its fountains and the activities of the local people. The ancient citadel, shown at first serene and regal, is later overrun by the transparent bodies of tourists, while the ‘videoterrorifico mirror’ of television reflects the frenzy of modern media.

These ‘variations on an intuited cinegraphy’ have been created entirely from material shot by Val del Omar between 1968-82. The newly commissioned atmospheric score is punctuated by his poetic declarations which invite comparison with both Federico García Lorca and Sun Ra.

Val del Omar envisaged a “cinematic vibration” that would be the vertex of his life’s work, a development and elaboration of the ‘Elementary Triptych’ in which he first presented his radical cinematic visions. The passage of images, which ranges from documentary to complete abstraction, is exquisitely photographed in lush colours and tonal monochromes. Delirious visual sequences mark the passage from the earthly world to a transcendental plane. The film is a meta-mystical allegory of life, death and rebirth led by the elementary forces of the universe, seeking unity between the spiritual realm, the ancient world and contemporary life, where images and thoughts flow free of time.

(Mark Webber)

Back to top

Date: 25 January 2005 | Season: Owen Land | Tags: George Landow, Reverence

REVERENCE: THE FILMS OF OWEN LAND (FORMERLY KNOWN AS GEORGE LANDOW): Programme One

January 2005—April 2007

International Tour

With Fleming Faloon and Film in Which There Appear, Owen Land was one of the first artists to draw attention to the filmstrip itself. Films like Remedial Reading Comprehension and Institutional Quality question the illusionary nature of cinema through the use of word play and visual ambiguity. By using the language of educational films he proposes an alternative logic for a medium that has become over theorised and manipulated He often parodies avant-garde film itself, mocking his contemporaries by alluding to their work (and previous films of his own), and also by imitating the serious approach of film scholars. On the Marriage Broker Joke manages to combine Japanese marketing executives, pandas, Little Richard, Liberace and Freud.

Owen Land, Remedial Reading Comprehension, 1970, 5 min

Owen Land, Fleming Faloon, 1963, 5 min

Owen Land, Film in Which There Appear Edge Lettering, Sprocket Holes, Dirt Particles, Etc., 1965-66, 4 min

Owen Land, Bardo Follies, 1967-76, 25 min

Owen Land, What’s Wrong With This Picture 1, 1971, 5 min

Owen Land, What’s Wrong With This Picture 2, 1972, 7 min

Owen Land, Institutional Quality, 1969, 5 min

Owen Land, On the Marriage Broker Joke as Cited by Sigmund Freud in Wit and its Relation to the Unconscious or Can the Avant-Garde Artist Be Wholed ?, 1977-79, 18 min

PROGRAMME NOTES

REVERENCE: THE FILMS OF OWEN LAND (FORMERLY KNOWN AS GEORGE LANDOW): Programme One

January 2005—April 2007

International Tour

REMEDIAL READING COMPREHENSION

Owen Land (formerly known as George Landow), USA, 1970, colour, sound, 5 min

Landow rejects the dream imagery of the historical trance film for the self-referential present, using macrobiotics, the language of advertising, and a speed-reading test on the definition of hokum. The alienated filmmaker appears, running uphill to distance himself from the lyrical cinema, but remember, “This is a film about you, not about its maker.”

FLEMING FALOON

Owen Land (formerly known as George Landow), USA, 1963, colour, sound, 7 min

A cinematic equivalent to the illusionistic portraiture of the Flemish painters. In his first 16mm film, Landow proposes that if we accept the reality offered to us by the illusion of depth on the flat plane of the screen, we can then assign reality to anything at will.

FILM IN WHICH THERE APPEAR EDGE LETTERING, SPROCKET HOLES, DIRT PARTICLES, ETC.

Owen Land (formerly known as George Landow), USA, 1965-66, colour, silent, 4 min

The ‘imperfections’ of filmmaking, which are normally suppressed, are at the core of a work that uses a brief loop made from a Kodak colour test. “The dirtiest film ever made,” is one of the earliest examples of the film material dictating the film content. It may seem minimal, but keep looking – there’s so much going on.

BARDO FOLLIES

Owen Land (formerly known as George Landow), USA, 1967-76, colour, silent, 25 min

A shot of a Southern Belle waving to group of tourists on a pleasure boat ride is looped, multiplied and then melted, creating psychedelic abstract images. These globular forms resemble cellular, microscopic or cosmic structures. “A paraphrasing of certain sections of the Tibetan Book of the Dead in motion picture terms.”

WHAT’S WRONG WITH THIS PICTURE? 1

Owen Land (formerly known as George Landow), USA, 1971, b/w & colour, sound, 5 min.

A found, utilitarian object, the overtly moralising educational film “How to be a Good Citizen”, is elevated to the status of ‘art’. The film is first presented unaltered and then in Landow’s colour facsimile, which is further modified by applying an opaque matte that creates a spatial paradox.

WHAT’S WRONG WITH THIS PICTURE? 2

Owen Land (formerly known as George Landow). USA, 1972, b/w, sound, 7 min

As Landow and his students were testing a new video camera, an elderly man began to talk to them about new technology. This impromptu conversation forms the basis for a comparison of spoken and written language. After being transferred to film, a transcript of the encounter is superimposed over the image.

INSTITUTIONAL QUALITY

Owen Land (formerly known as George Landow), USA, 1969, colour, sound, 5 min

The film is constructed around a found soundtrack in which a strict female voice delivers a test of perception and comprehension. As this test continues, the relationship between sound and image becomes detached and they follow separate paths, a consequence of the filmmaker losing interest in his subject.

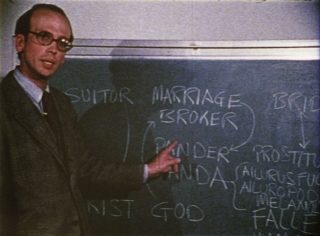

ON THE MARRIAGE BROKER JOKE AS CITED BY SIGMUND FREUD IN WIT AND ITS RELATION TO THE UNCONSCIOUS OR CAN THE AVANT-GARDE ARTIST BE WHOLED ?

Owen Land (formerly known as George Landow), USA, 1977-79, colour, sound, 18 min

“Two pandas, who exist only by textual error, run a shell game for the viewer in an environment with false perspectives. They posit the existence of various films and characters, one of which is interpreted by an academic as containing religious symbolism. Finally, Sigmund Freud’s own explanation is given by a sleeper awakened by an alarm clock.” (P. Adams Sitney)

Back to top

Date: 26 January 2005 | Season: Owen Land | Tags: George Landow, Reverence

REVERENCE: THE FILMS OF OWEN LAND (FORMERLY KNOWN AS GEORGE LANDOW): Programme Two

January 2005—April 2007

International Tour

Diploteratology was produced by burning celluloid to create abstract, organic imagery. As well as exploring the material of cinema, Owen Land has exposed film’s innate ability to transcend the moment and propose surrogate ‘facades’ of reality. In Wide Angle Saxon, an ordinary, middle-aged man undergoes a conversion experience whilst watching an avant-garde film, and in New Improved Institutional Quality, a similar character undertakes an IQ test which takes him deep inside his imagination. A sequence of works from the mid-1970s arise from the filmmakers’ inquiry into Christianity, but are far from evangelical.

Owen Land, The Film that Rises to the Surface of Clarified Butter, 1968, 9 min

Owen Land, Diploteratology, 1967-78, 7 min

Owen Land, “No Sir, Orison!”, 1975, 3 min

Owen Land, Wide Angle Saxon, 1975, 22 min

Owen Land, Thank You Jesus for the Eternal Present, 1973, 6 min

Owen Land, A Film of Their 1973 Spring Tour Commissioned by Christian World Liberation Front of Berkeley, California, 1974, 12 min

Owen Land, New Improved Institutional Quality: In the Environment of Liquids and Nasals a Parasitic Vowel Sometimes Develops, 1976, 10 min

PROGRAMME NOTES

REVERENCE: THE FILMS OF OWEN LAND (FORMERLY KNOWN AS GEORGE LANDOW): Programme Two

January 2005—April 2007

International Tour

THE FILM THAT RISES TO THE SURFACE OF CLARIFIED BUTTER

Owen Land (formerly known as George Landow), USA, 1968, b/w, sound, 9 min

An illustrator is drawing figures that resemble Tibetan deities. He can’t believe his eyes when they appear to come to life and dance on the paper, taking on qualities we might associate with Disney characters. They appear trapped between 2D and 3D space, an eerie limbo which is amplified by the sinister loop of the soundtrack.

DIPLOTERATOLOGY

Owen Land (formerly known as George Landow), USA, 1967-78, colour, silent,, 7 min

A revision of BARDO FOLLIES, subtitled “the study newly formed monstrosities”. Its images represent visual phenomena seen during a passage into the afterlife, but also evoke the cellular structure of the filmstrip, and of our own bodies. “The suggestion is that death (destruction of the original image) is not an end but merely the next stage.”

“NO SIR, ORISON!”

Owen Land (formerly known as George Landow), USA, 1975, colour, sound, 3 min

After singing a vivacious song of love in the aisle of a supermarket, the performer kneels down to ask forgiveness for those involved in the commercial food industry, which substitutes natural produce with non-nutritious commodities. Orison means prayer. The title of the film (a palindrome) is the answer to a question.

WIDE ANGLE SAXON

Owen Land (formerly known as George Landow), USA, 1975, colour, sound, 22 min

An interpretation of The Confessions of Saint Augustine, featuring an ordinary middle-aged man who undergoes a conversion experience whilst watching an experimental film. The film is by Al Rutcurts (think about it) and Earl is so bored that his mind starts to wander. He realises that his possessions may be a barrier between himself and God and determines to something about it.

THANK YOU JESUS FOR THE ETERNAL PRESENT

Owen Land (formerly known as George Landow), USA, 1973, b/w & colour, sound, 6 min.

A rapturous audio-visual mix that “deliberately seeks a hidden order in randomness.” The film combines the face of a woman in ecstatic, contemplative prayer with shots of an animal rights activist, and a scantily clad model advertising Russian cars at the International Auto Show, New York.

A FILM OF THEIR 1973 SPRING TOUR COMMISSIONED BY CHRISTIAN WORLD LIBERATION FRONT OF BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA

Owen Land (formerly known as George Landow), USA, 1974, colour, sound, 12 min

A radical Christian group’s lecture tour of US colleges was filmed in the cinema verité tradition, with hand held camera, sync and wild sound. To avoid making a conventional documentary, the filmmaker created a dynamic collage by stroboscopically editing together pairs of scenes using a rapid rhythm of three-frame units.

NEW IMPROVED INSTITUTIONAL QUALITY: IN THE ENVIRONMENT OF LIQUIDS AND NASALS A PARASITIC VOWEL SOMETIMES DEVELOPS

Owen Land (formerly known as George Landow), USA, 1976, colour, sound, 10 min

The IQ test soundtrack is re-used in an entirely new work that is concerned more with the effects on the examinee, who enters a Chinese box of impossible perspectives in a hyper-realistic living room. He briefly escapes the oppressive environment of the test but passes into the imagination of the filmmaker, where he encounters images from previous films.

Back to top

Date: 2 June 2005 | Season: The Write Stuff

RITE WORDS, ROTE ORDER

Thursday 2 June 2005, at 7pm

London Corsica Studios

An evening of films that use written or spoken language to verbalise and hypnotise. A selection of works which, to a greater or lesser extent, use words and text to communicate their message or impart their expression. An event to educate, fascinate and possible aggravate. Inform and reform.

From socio-political films by Rhodes and Wieland through to the use of humour by Smith and Snow, and plenty more besides, here are some works that can easily be read (and I mean literally). For slight relief from the pressures of the text, the screening will be divided (but not interrupted) by unusual recordings of aural stimulation (speech / sound art / poetry / etc.) by great writers, advanced artists and crazy crackpots. You Never Heard Such Sounds In Your Life. Expect to be subjected to the sounds of Alvin Lucier, William Burroughs, John Cage, Gertrud Stein, concrete poets, dial-a-poets, Futurists, Dada’s, mothers and children, the obscurely wilful and the wilfully obscure.

“History as she is harped, rite words in rote order.”

Marcel Duchamp, Anaemic Cinema, France, 1925, b/w, silent, 7 min

John Smith, Associations, UK, 1975, colour, sound, 7 min

Martha Haslanger, Syntax, 1974, colour, sound, 13 min

Lis Rhodes, Pictures on Pink Paper, UK, 1982, colour, sound, 35 min

Joyce Wieland, Rat Life and Diet in North America, Canada, 1968, colour, sound, 16 min

Michael Snow, So is This, Canada, 1982, silent, colour, 45 min

Stan Brakhage, First Hymn to the Night – Novalis, USA, 1994, colour, silent, 4 min

Curated by Mark Webber for The Write Stuff Literary Festival at Corsica Studios.

PROGRAMME NOTES

RITE WORDS, ROTE ORDER

Thursday 2 June 2005, at 7pm

London Corsica Studios

ANAEMIC CINEMA

Marcel Duchamp, France, 1925, b/w, silent, 7 min

Duchamp used the initial payment on his inheritance to make a film and to go into the art business. The film, shot in Man Ray’s studio with the help of cinematographer Marc Allégret, was a seven-minute animation of nine punning phrases by Rrose Sélavy. These had been pasted, letter by letter, in a spiral pattern on round black discs that were then glued to phonograph records; the slowly revolving texts alternate with shots of Duchamp’s Discs Bearing Spirals, ten abstract designs whose turning makes them appear to move backward and forward in an erotic rhythm. The little film, which Duchamp called Anemic Cinema, had its premiere that August at a private screening room in Paris. (Calvin Tomkins)

ASSOCIATIONS

John Smith, UK, 1975, colour, sound, 7 min

Images from magazines and colour supplements accompany a spoken text taken from ‘‘Word Associations and Linguistic Theory’’ by Herbert H. Clark. By using the ambiguities inherent in the English language, Associations sets language against itself. Image and word work together/against each other to destroy/create meaning. (John Smith)

SYNTAX

Martha Haslanger, 1974, colour, sound, 13 min

As the word “syntax” implies, this film deals with the way in which images and sounds come together. Its main concern, however, goes deeper, and resides within a more personalized syntax: a process of retaining a narration. Syntax is a small gem, exhibiting … a kind of joyful, competent wit and strength. Haslanger prowls her camera through several rooms in an ordinary middle class house while her voice-over describes what we are about to see or have seen, never what is actually on the screen, wringing the changes of the relationship of the spoken word, image and the printed word. It is a wonderfully self-contained and seductive film. (Jump Cut)

PICTURES ON PINK PAPER

Lis Rhodes, UK, 1982, colour, sound, 35 min

In Pictures on Pink Paper, the voices of three women describe experiences of domestic life, gradually become identifiable as belonging to specific individuals. Different generations are represented in the voices of the three women, and also in the generations of images used. Here, Rhodes engages with the representative quality of the images – throughout the film photocopies and super 8 film are blown up and re-presented. This film seeks to find a female voice, but avoids generalization of a single narrative through the interweaving of these voices. In Pictures on Pink Paper the authoritative voice is slipping between appearing to be one woman’s voice and thoughts, to the experiences of three different women. Minnie, a Cornishwoman, narrates the past, Kate imitates accents and voices, and Lis Rhodes’ voice becomes identifiable as the filmmaker. This film asks how women’s oppression can be articulated without mimicking that very expression and language which produces the unbalance. In spite of being structured around these voices this film denies narrative structure – even time here is broken down. Pictures on Pink Paper highlights the gaps between and explores language as a creator, rather than a symptom, of gender relations. It seeks to ask how a female voice can be found without reducing all female experience to a generalization. As with many of Lis Rhodes’ films, Pictures on Pink Paper looks to the ways in which women are associated with nature. The alignment of women with nature and men with culture is embedded within language: unlike French and Spanish the English language is non-gendered grammatically, yet the female pronoun is regularly used for ‘natural’ objects. Language is powerful: we become inscribed within language, and Lis Rhodes challenges these assumptions by problematising language. (Lisa Le Feuvre, www.luxonline.org)

�RAT LIFE AND DIET IN NORTH AMERICA

Joyce Wieland, Canada, 1968, colour, sound, 16 min

Wieland returned to the kitchen table with Rat Life and Diet in North America in 1968, a study of her pet gerbils. She filmed them in extreme close-up among cups and dinner plates, eliminating all sense of spatial depth and place, producing luscious images teeming with texture and colour. More and more, Wieland’s films were distinguished by this sensuality, setting her apart from her male counterparts in the Structuralist movement. Interestingly, Rat Life and Diet in North America contains a narrative thread, transforming the gerbils into political prisoners who escape their American oppressors, played by Wieland’s cats. They make their way to Canada where they set up an organic farm and appear to live happily ever after until an invasion by the United States. Influenced by Vietnam War protests, this political allegory is one of the most hilarious denouncements of American imperialism found in any genre. The film also betrays a basic Canadian fear and coincides with Wieland’s increasingly nationalistic concerns. Discussions of such concerns were commonplace in Canada at the time and Wieland felt drawn in, even from as far away as New York City. Rat Life and Diet in North America marked the beginning of a shift in her career. Moving away from the purely formal, Wieland plunged head-long into the political. As she did, she felt herself both disconnected from and rejected by the very movement that had initially inspired her. (Barbara Goslawski, Take One)

SO IS THIS

Michael Snow, Canada, 1982, silent, colour, 45 min

“With formalist belligerence, So Is This threatens to make its viewers ‘laugh cry and change society,’ even promising to get ‘confessional.’ Although the film does reflect Snow’s personality – his Canadian-ness, preference for humor over irony, obsession with art world chronology (who did what first) – its only confession is the tacit acknowledgement that he’s sensitive to criticism. Snow takes full advantage of his film’s system of discourse to twit restless audiences. A lot of this is pretty funny but So Is This is more than a series of gags. Snow manages to de-familiarize both film and language, creating a kind of moving concrete poetry while throwing a monkey wrench into a theoretical debate (is film a language?) that has been going on sporadically for 60 years. If you let it, Snow’s film stretches your definition of what film is – that’s cinema and So Is This. (J. Hoberman, The Village Voice)

FIRST HYMN TO THE NIGHT – NOVALIS

Stan Brakhage, USA, 1994, colour, silent, 4 min

This is a hand-painted film whose emotionally referential shapes and colors are interwoven with words (in English) form the first Hymn to the Night by the late 18th Century mystic poet Friedrich Philipp von Hardenberg, whose pen name was Novalis. The pieces of text which I’ve used are as follows: ‘the universally gladdening light … As inmost soul … it is breathed by stars … by stone … by suckling plant … multiform beast … and by (you). I turn aside to Holy Night … I seek to blend with ashes. Night opens in us … infinite eyes … blessed love. (Stan Brakhage)

Back to top

Date: 3 June 2005 | Season: The Write Stuff

PATTERNS OF SPEECH

Friday 3 June 2005, at 7pm

London Corsica Studios

Four videotapes which each explore variations in spoken language. “Mesostics” are poems in which a string of vertical letters, one from each line, spells a name or word. John Cage’s calm and sage delivery of these phrases sits in stark contrast with the deranged performance by actor Tim Thompson, in Paria, which is based on workshops condicted with prisoners at a correctional facility. Taped by video pioneers the Vasulka’s, these disturbing monologues are further unhinged by their technological distortion of the image. The second half of the programme features tapes by Peter Rose, who has conducted a deep investigation of language and text throughout his work, whilst demonstrating an incisive sense of humour. He often uses invented words, subtitles, sign language and direct address to spin yarns that examine syntax and patterns of speech, while simultaneous exploring the nature of film and video media itself. This is a rare screening of two seminal videotapes that are practically unknown in the UK.

John Cage/Soho TV, 36 Mesostics Re. and not Re. Duchamp, USA, 1978, videotape, 26 min

Woody & Steina Vasulka, Pariah, USA, 1984, videotape, 26 min

Peter Rose, The Pressures of the Text, USA, 1983, videotape, 17 min

Peter Rose, Digital Speech, USA, 1984, videotape, 13 min

Curated by Mark Webber for The Write Stuff Literary Festival at Corsica Studios.

PROGRAMME NOTES

PATTERNS OF SPEECH

Friday 3 June 2005, at 7pm

London Corsica Studios

36 MESOSTICS RE. AND NOT RE. DUCHAMP

John Cage / Soho TV, USA, 1978, videotape, 26 min

“Like acrostics, mesotics are written in the conventional way horizontally, but at the same time they follow a vertical rule, down the middle not down the edge as in an acrostic, a string spells a word or name, not necessarily connected with what is being written, though it may be. This vertical rule is lettristic and in my practice the letters are capitalized. Between two capitals in a perfect or 100% mesostic neither letter may appear in lower case. …. In the writing of the wing words, the horizontal text, the letters of the vertical string help me out of sentimentality. I have something to do, a puzzle to solve. This way of responding makes me feel in this respect one with the Japanese people, who formerly, I once learned, turned their letter writing into the writing of poems. In taking the next step in my work, the exploration of nonintention, I don’t solve the puzzle that the mesostic string presents. Instead I write or find a source text which is then used as an oracle. I ask it what word shall I use for this letter and what one for the next, etc. This frees me from memory, taste, likes, and dislikes. Words come first from here and then from there. The situation is not linear. It is as though I am in a forest hunting for ideas.” (John Cage)

PARIAH

Woody & Steina Vasulka, USA, 1984, videotape, 26 min

In 1983 Tim Thompson was an artist in residence at the Las Lunas correctional facilities, New Mexico, conducting a theatre workshop. While working with the inmates, he became familiar with theirs life stories, their vocabulary and their physical demeanour. This became the source material for a composite character, later portrayed in his one-man theater production Pariah in Santa Fe. This turned out to be his last production and performance. Tim Thompson, one of the most brilliant performers we ever met has turned full time to the digital arts in both moving and still images. The performance was taped in Eve Muir’s studio in Santa Fe in May of 1984, and edited later with the addition of the Rutt/Etra scan-processing effects. The work as a whole is seldom seen, however segments of Pariah have become a part of Steinas MIDI Violin repertoire. (Vasulkas)

THE PRESSURES OF THE TEXT

Peter Rose, USA, 1983, videotape, 17 min

The Pressures of the Text integrates direct address, invented languages, ideographic subtitles, sign language and simultaneous translation to investigate the feel and form of sense, the shifting boundaries between meaning and meaninglessness. A parody of art/critic-speak, educational instruction, gothic narrative, and pornography, it has been performed as a live work at major media centres and new music festivals in the US and Europe. The piece was written, directed and delivered by Peter Rose; co-directed by Jessie Lewis; with sign language and ideographic symbols by Jessie Lewis; and with English simul-translation by Fred Curchack. (Peter Rose)

DIGITAL SPEECH

Peter Rose, USA, 1984, videotape, 13 min

Digital Speech uses a traveller’s anecdote, a perverse variant of a classic Zen parable, as a vehicle for an exploration of language, thought and gesture. The tape plays with the nature of narrative, with ways of telling, performing and illustrating, and uses nonsense language, scat singing and video rescan for comic comment. (Peter Rose)

Back to top

Date: 29 October 2005 | Season: London Film Festival 2005 | Tags: London Film Festival

VIDEO VISIONS

Saturday 29 October 2005, at 2pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

Manuel Saiz, Specialized Technicians Required: Being Luis Porcar, Spain, 2004, 2 min

A well-known Spanish voice-over actor gives a witty demonstration of the art of dubbing.

Jacqueline Goss, How to Fix the World, USA-Uzbekistan, 2004, 28 min

A 1930s Soviet literacy study of Central Asian farmers is brought to life in this stylized digital animation. The responses of the collective workers are both humorous and revealing: the clash of ideologies is as apparent as the difference between the cognitive processes of written language and their oral tradition.

Guy Ben-Ner, Wild Boy, Israel-USA, 2004, 17 min

With a minimum of means, Ben-Ner tames and domesticates a young boy discovered living like a wild animal in the woods. A real kitchen sink drama told with the delicate humour of classic silent cinema.

Chris Haring & Mara Mattuschka, Legal Errorist, Austria, 2005, 15 min

Stephanie Cumming’s astonishing dance performance has her twitching and thrashing like an android on a bad data day. Abandoned in a dark void, the Legal Errorist is a brain in overload, a ‘creature that cannot stop crashing.’

Oliver Pietsch, Tuned, Germany, 2004, 14 min

Scenes from mainstream movies skilfully edited into a stream of unconsciousness and elevated by an emotive sound mix. Sneak a peek at high times in Hollywood with this compilation of fake intoxication.

Kenneth Anger, Mouse Heaven, USA, 2005, 10 min

Not a work we would have expected from the Magus who was reportedly working on a production of Aleister Crowley’s ‘Gnostic Mass’. Mouse Heaven is a lively romp through the world’s largest collection of antique Mickey memorabilia, assembled (like the masterpiece Scorpio Rising) as a series of vignettes to different musical tracks, ranging from The Boswell Sisters to – bizarrely – the Proclaimers! Puckish fun from the maestro.

PROGRAMME NOTES

VIDEO VISIONS

Saturday 29 October 2005, at 2pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

SPECIALIZED TECHNICIANS REQUIRED: BEING LUIS PORCAR

Manuel Saiz, Spain, 2004, video, colour, sound, 2 min

Manuel Saiz has done it! The Famous Hollywood Actor has once again gracefully accepted to be or not to be what he is. Witness the film that inspired the pun in the title of this short video – he is not afraid of a few digs at his person and status. He probably has a small army of agents, managers and assistants around him, to keep all those who are trying to make use of him because of his name at a distance. Perhaps Manuel Saiz was lucky, perhaps he knows the friends of the friends of – perhaps he has been waiting on the doorstep and hanging on the phone for months, driving the whole army crazy. He probably just used a sympathetic argument that struck the right cord: Would the actor who likes role reversals for once lend his charismatic voice to a man who is used to doing precisely that? A man who always obligingly keeps out of sight, but who is, to the Spanish speaking part of the world population, the actor’s mouthpiece, and therefore to a great extent ‘is him’. Being Luis Porcar is part of the series Specialized Technicians Required, and it makes you wonder who actually is the specialized technician in this construction. Is it the main character, the man who does the dubbing, or is it the artist himself, who nowadays has to master so many different skills in order to be able to carry out his profession properly? (Vinken & Van Kampen)

HOW TO FIX THE WORLD

Jacqueline Goss/USA-Uzbekistan 2004, video, colour, sound, 28 min

How To Fix The World is a digitally animated video adapted from Soviet psychologist A.R. Luria’s research in Central Asia in the 1930s. In Luria’s book ‘Cognitive Development: Its Social and Cultural Foundations’, the author presents data collected from three years of interviews with Uzbek and Kyrgyz farmers who lived on or near the Soviet-sponsored collective farms in the 1930s. During this time, the Soviets introduced literacy programs into these primarily Muslim oral-based agricultural communities. Interested in documenting the cognitive changes that people experience when learning to read, Luria also captured the cultural conflict of Soviet Socialism and Islam. In How To Fix The World, the conversations transcribed into Luria’s book are brought to life via simple animation techniques. Max Penson’s photographs of the collective farms serve as the visual model for the animations and they play against a backdrop of landscape images shot in Central Asia in 2004. At once humorous, conflicting and revelatory, these conversations between Luria and his subjects illustrate a particular historical moment when one culture attempted to transform another in the name of education and modernization. The subtleties of this transformation are found in the words exchanged and documented seventy years ago. (Jacqueline Goss)

www.jacquelinegoss.com

WILD BOY

Guy Ben-Ner/Israel-USA 2004, video, colour, sound, 17 min

Wild Boy tells the story of a wild child and his educator, a story of power relations and the fantasy of bringing somebody up after one’s own image. It is the story of every parent-child rearing, but more than that, it is a story of a director and his child-actor, raising the question of what it means to direct a child, to contain a child inside a fixed frame, to command him in and out of the frame (as if it is his private room). On another level, it also raises the possibility of looking at early cinema (the “cinema of attractions” as was coined by Tom Gunning), as a mute wild child that was tamed, eventually, by language (sound, narrative). Wild Boy is based on several case histories, some myths, some educational manuals and refers to a wide range of movies, from old photos left of the vaudeville acts by father and son Buster and Joe Keaton, through Truffaut’s Wild Child to The Kid by Chaplin. (Guy Ben-Ner)

LEGAL ERRORIST

Chris Haring & Mara Mattuschka, Austria, 2005, video, colour, sound, 15 min

A performance of transformation, a transformance, changes its medium and encounters a camera, which plays dance music – under the secret eye of a room that bends and twists along with it. The Legal Errorist – personified by the dancer Stephanie Cumming – is a creature that cannot stop crashing. The sudden overpowering by the ‘error’, the system error, engenders the creature’s obsession. She commences with great relish through a series of transformations; that which hits upon the limits of a simple machine serves as a learning program for the Legal Errorist. Film and performance – parallel projection or articulated interference? Massively, like a mountain, the body of the Errorist falls to the floor and lands with an obstinate sound whose source seems remote from anything human. As though she were her own director, she speaks animatedly with numerous invisible colleagues. She speaks to the microphone, not through it: an eerie animated world of objects, which become fellow creatures when one creature cannot categorise herself precisely. “What?!?” roars the Legal Errorist defiantly – as though to a higher being in the dark and not the diffuse collective of the audience. And she begins to lure the gaze through the catalogue of her body parts. The voyeur’s fatally bundled attention seems inverse to the body set against it, anamorphically distorted by the extremely wide- angled lens. Does this gaze document a foul subjectivity or does this closed world look back as its own lens? The camera is a shrewd ally in the counterattack launched by the body on display. (Katherina Zakravsky)

TUNED

Oliver Pietsch, Germany, 2004, video, colour, sound, 14 min

Portraits of people consuming drugs taken from film history are edited together in rapid succession. All appear radically isolated, their inward-looking eyes looking out from the screen, appearing helpless and disorientated. Their trip alternates between giggling lust and panicked anxiety, turning increasingly into blank horror. The paradox: In these edited sequences, the crazed and overwrought figures once again build a community whose unifying core is the flight from the community and the search for the true self in itself. The film can here be understood as a metonym for western culture. (Ute Vorkoeper)

MOUSE HEAVEN

Kenneth Anger, USA, 2005, video, colour, sound, 10 min

It’s a study of animated toys of a rare nature. These are collectables of early Walt Disney toys. I’ve always loved Mickey Mouse since I was a little boy and I’m outraged about the current Disney company’s attitude to Mickey Mouse. I mean they think they own it, but all the children of the world own Mickey Mouse. And I have devised a way to star Mickey Mouse in a film that the current Disney company can’t legally object to, by filming an antique toy collection of early Disney toys. And it’s just a coincidence all those toys happen to be Mickey Mouse. I’m actually being very respectful of early Mickey Mouse. I hate later Mickey Mouse, because from Fantasia on, the Disney people decided to humanise the mouse, remove his tail – which is a kind of castration – and turn him into a little boy who is a sort of a goody-two-shoes. And he’s no longer the mischievous, sadistic mouse that he was in the beginning. He used to do nasty little tricks like twist the udders of cows and things like that. And that’s the only mouse I’m interested in, this kind of demon ‘fetish’ figure. (Kenneth Anger)

Back to top

Date: 29 October 2005 | Season: London Film Festival 2005 | Tags: London Film Festival

LITERARY LANDSCAPES

Saturday 29 October 2005, at 4pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

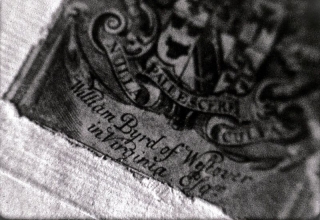

David Gatten, The Great Art of Knowing, USA, 2004, 37 min

‘On either side of a Life find a Library before and an Auction after: consider these figures as the sites for a collection created for the purposes of division and dispersal. This chapter of my ongoing exploration of the Byrd library finds its name and shape within a single volume from that collection: Kircher’s 17th century encyclopaedia. Herein find tangled texts and crossed destinies, filled with figures at once buried deep and tossed high by History, lined with traces of a forbidden romance. Love finds purchase between tightly shelved volumes.’ (DG)

Matthew Noel-Tod, Nausea, UK, 2005, 60 min

Nausea is a synthesis of text and image that draws inspiration from Impressionism, On Kawara, Barnett Newman and the existential diary by Jean-Paul Sartre from which it adopts its title. The video footage is a journal of observations shot entirely on a mobile phone. Crudely low resolution, it retains a fuzzy warmth and familiarity rather than the cold, impersonal qualities of much digital technology, challenging a ‘certain end-point in cinema, wherein we only ever imagine and receive mediated images.’ (MNT)

PROGRAMME NOTES

LITERARY LANDSCAPES

Saturday 29 October 2005, at 4pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

THE GREAT ART OF KNOWING

David Gatten, USA, 2004, 16mm, b/w, silent, 37 min

On either side of a Life find a Library before and an Auction after: consider these figures as the sites for a collection created for the purposes of division and dispersal. The journey this time moves from the first light at dawn to the last rays of a sunset, reflected and refracted. In between find dry Fall turn toward the shadows of Spring and the stillness of death sparked by the singularities of a transcendental field. Find yourself resting uneasily half way up the stairs: Something has left the body, yet the body remains: what has left is on its way Elsewhere but cannot help but look back: this look animates the world and makes possible this Theory of Flight in the form of a bibliography. From Leonardo da Vinci to Jules-Etienne Marey practitioners of a certain mode of transcendental empiricism turned repeatedly to combinations of words and images describing the flight of birds.

In 1726 William Byrd returned to Westover in Virginia and began construction of a garden soon to be called “the finest in the country, filled with the charming colours of the Humming Bird.” In a parallel pursuit, he collected the largest library in the colonies to serve as mirror for his mind and testament to his knowledge. Evelyn Byrd was fond of sketching the birds in the garden. Her interest was more than aesthetic and scientific; she devised a very different use for her father’s vast library. This chapter of my ongoing exploration of the Byrd library finds its name and shape within a single volume from that collection: Athanasius Kircher’s 17th century encyclopaedia, ‘The Great Art of Knowing’. Herein find tangled texts and crossed destinies, filled with figures at once buried deep and tossed high by History, lined with traces of a forbidden romance. Love finds purchase between tightly shelved volumes. In the spaces between the letters. In the lines themselves. An antinomian cinema seems possible. A gentle iconoclasm? The image is always backwards in a mirror. The story unfolds slowly.

Part IV of the Byrd project. (David Gatten)

NAUSEA

Matthew Noel-Tod, UK, 2005, video, colour, sound, 53 min

Existentialism is present in so many developments in 20th Century Art History and Sartre’s debts lie as much with Cezanne and Van Gogh as with Descartes and Heidegger. The whole text of Sartre’s book ‘Nausea’, at a speed of one word per frame, lasts for 53:37 minutes, so I used this duration as a base for editing. The text was then cut up and ordered randomly – missing every other word, backwards, etc, so that what is seen is literally just ‘words’, not Sartre’s words. The text is sometimes slowed down and edited to suggest a narrative, drawing unique relationships between word and image. In 2004, I started using a mobile phone video camera to record daily images. Like early cinematograph-style inventions, this technology’s legacy seems destined be through the very simple recording of people and their backgrounds. I thought it could support an attempt to record footage that was free from mediation, which was instinctive and free from analysis and artifice, and I recorded my life for roughly a year. The variability of the video frame rate and image compression became mostly predictable, but still surprised me with unpredictable rendering of one image or another. The most constant of these artefacts was the camera’s inability to register extreme areas of light, mostly apparent when filming the sun. These areas appeared black. Many things didn’t record ‘well’, such as people and movement. Other things took on a magical, painterly aura when filmed with the phone camera – skies, landscapes, still lifes. The pure colour sections are enlargements of certain clips to the scale of one pixel filling the screen. Other ‘abstract’ images, which appear like camera-less process driven distortion, are in fact the limitation of the camera to record certain images, notably ‘nothing’. Echoing the ideas of phenomenological discovery, reflexive consciousness and modernist redemption through art which inspired this video, the often casual nature of the images in Nausea comes ultimately from an examination of a certain ‘end-point’ in cinema, wherein we only ever imagine and receive mediated images – images of images. Is creative instinct in filmmaking purely an extension of this mediated post-modern situation? A failed romantic, moribund and nostalgic ideal? Or a valid area for self-examination and analysis of aesthetics? (Matthew Noel-Tod)

Back to top