A programme to demonstrate the magical properties of colour as it was manipulated by expert film artists. The abstract film-makers developed techniques in order to represent their cosmic visions without the use of recognisable imagery. Early pioneers like the Whitney Brothers made unique innovations. La Couleur De La Forme is like a masterclass of editing and printing technique. Jordan Belson was visual director of the legendary Vortex Concerts and went on to make special effects sequences in Hollywood for films like The Right Stuff. He rarely shows his work today because time has faded the perfect colours. Stan Vanderbeek made animated collages before developing multi screen expanded cinema pieces. Diffraction Film presents a sea of colour and was used in USCO’s sound and light presentations. Pat O’Neill and Scott Bartlett were two of the first film-makers to utilise video in their work. The Tattooed Man is a major work of graphic invention and image manipulation by the poet and film-maker Storm De Hirsch. Tom Chomont’s Oblivion provides stereoscopic visions when viewed through 3D glasses.

VISUAL ALCHEMY

Sunday 1 November 1998, at 7:00pm

London Lux Centre

Many of the early experimental films were composed of abstract shapes, usually put together in such a way as to visually interpret a piece of music. As with the poetic film, the abstract school had its roots in the European cinema of the 1920s. The films of Oskar Fischinger, Hans Richter, Viking Eggeling and Man Ray were highly influential, as were those by Len Lye (from New Zealand) and Norman McLaren (a Scot), who each made an incredible series of films in the 1930s under the direction of John Grierson at the GPO Film Unit. But it was in America, after pioneering work of the 1940s by Mary Ellen Bute, Douglas Crockwell and the Whitney brothers, that the development of the abstract film really got underway, particularly in California where the Whitneys, Jordan Belson, Hy Hirsh, Harry Smith, and Ian Hugo all worked through the 1950s.

John and James Whitney first worked together on Variations (1941-43) photographing abstract forms that were animated on cards. For their Film Exercises (1943-44) they developed a machine that could produce electronic music directly onto film in perfect sync with the images. When they began to work independently, John made films without animation using an illuminated oil bath before beginning to use computer effects in Catalog (1961). As computer and video technology progressed his films such as Binary Bit Patterns (1969), Permutations (1967) and Matrix 1,2,3 (1971-73) became more and more complex. James Whitney continued to work manually and after destroying his first Film (1945-50) he spent many years making the incredible Yantra (1950-58) by hand-drawing dots onto cards and optically printing them layer upon layer. Yantra means ‘machine’ in Sanskrit and the film can be seen to be an instrument for meditation. It was originally conceived as a silent film and became married to its soundtrack by Dutch composer Henk Badings after projection at one of the Vortex Concerts.

YANTRA

James Whitney, USA, 1950-58, 16mm, colour, sound, 10 min

“The repeated accelerating flickers between black and white or solid colour frames photo-kinetically induce an ‘alpha’ meditative state. Into the climax of these generative alternations of spectral opposites, the dots enter and enact movements which are carefully ‘choreographed’ in the sense of purely visual ‘music’. The screen is scrupulously sustained as a flat expository surface, and a reflexive consciousness of the film material process is maintained by the use of flickers, transparent / white backgrounds, scratches, and solarized, step-printed episodes, in which the hand-wrought, irregular textures also recall James’ expertise as a raku potter and the alchemical processes of transmuting elements, in this case the coloured chemicals of the film emulsion by the ‘solar’ fire.” (from William Moritz’ essay The Non-Objective Film: The Second Generation, in the book Film As Film, 1979)

There is frustratingly little reliable information about the life and work of Hy Hirsh. He was born in Chicago in 1911 and began to make films in California, collaborating with Roger Barlow, LeRoy Robbins and Harry Hay on Even As You And I (1937), a satire on Surrealism containing a scene in which a baby is laid on a plate, sliced up and served for dinner. Ten years later he worked with Sidney Peterson on The Cage, Clinic Of Stumble and Horror Dream (all 1947). It is thought that he spent most of the 1950s living in Europe, developing complex abstract films which usually featured oscilloscopes and optical printing. Some of the oscilloscope footage was used in the Vortex Concerts of 1957-59. Hirsh died of a heart attack while driving through the Place De La Concorde in Paris in 1960. All his personal effects were seized by the police as evidence for an investigation into his long term involvement in marijuana and hashish trafficking. (He stored the dope in film cans). When the films were returned to his family and subsequently passed on to Bob Pike and the Creative Film Society, many were lost, unlabelled or in an extremely poor condition that made it impossible to assemble and present his work the way it was intended. It appears that he often preferred to project the films himself, re-editing them or synchronising different soundtracks for each specific occasion. Hirsh also experimented with double screen projection and polaroid stereoscopic 3D. La Couleur De La Forme (1952) is one of his most complex films and demonstrates his mastery of editing and printing techniques.

LA COULEUR DE LA FORME

Hy Hirsh, USA, 1952, 16mm, colour, sound, 5 min

“With La Couleur De La Forme, Hirsh more than ever justifies a critic’s description as ‘the Matisse of the cinema’. Partly collage, partly a study of movement, Hirsh’s technique does on film what kinetic art does in sculpture. Mixing positives and negatives, solarization, double exposure etc., to produce a mental freewheeling of images, a brilliant kaleidoscopic dreamworld.” (London Film-Makers’ Co-Op Catalogue, 1977)

Jordan Belson is one of the masters of abstract cinema, but his values are so high that it is almost impossible to see his work on the screen. Since the 1970s he has withdrawn his films from distribution due to his unhappiness with projection facilities and frustration over the changes in colour that have faded his films over time. He began his career as a painter in Beat-era San Francisco and was a close associate of Harry Smith. His first two films, Transmutation (1947) and Improvisations No. 1 (1948), were made directly from painted scrolls, and have since been destroyed. In the early 1950s he made a series of stop-motion animations including Mambo (1951) Bop Scotch (1953) and the unfinished LSD (1954). After a few more years concentrating on painting, Belson teamed up with Henry Jacobs and became Visual Director of the legendary Vortex Concerts at the Morrison Planetarium (1957-59), projecting abstract and cosmic imagery to accompany electronic music. Belson’s first masterpiece Allures (1961) developed out of this experience to become a “mathematically precise film on the theme of cosmogenesis”. Re-Entry (1964) followed and is a combination of space travel and the journey of the soul from death to rebirth. Belson continued to work on a phenomenal series of metaphysical films including Samadhi (1967), an incredible exposition of cosmic consciousness.

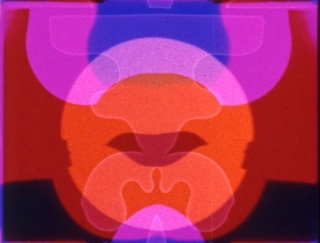

ALLURES

Jordan Belson, USA, 1961, 16mm, colour, sound, 9 min

“I think of Allures as a combination of molecular structures and astronomical events mixed with subconscious and subjective phenomena – all happening simultaneously. The beginning is almost purely sensual, the end perhaps totally nonmaterial. It seems to move from matter to spirit in some way. Oskar Fischinger had been experimenting with spatial dimensions, but Allures seemed to be outer space rather than earth space. After working with some very sophisticated equipment at Vortex, I learned the effectiveness of something as simple as fading in and out very slowly.” (Jordan Belson talks to Gene Youngblood for the article The Cosmic Cinema of Jordan Belson in Film Culture #48-49, 1970)

RE-ENTRY

Jordan Belson, USA, 1964, 16mm, colour, sound, 6 min

“In Re-Entry he successfully synthesises the Yogic and the cosmological elements in his art for the first time by forcefully abstracting and playing down both of them. The great advance of this film over all of his earlier work consists in the organisation of its images into an intentional structure. From an opening of symmetrically ordered dots, moving along the plane of the flat screen and along illusionary lines of depth, the film moves, as if impelled by a directional force, through a fluid series of gaseous colours with a single metaphoric allusion to solar prominences.” (P. Adams Sitney in his book Visionary Film, 1974)

Stan Vanderbeek is widely regarded as the first to use the term “Underground Film” to describe his films and others like them. His early films were collages in which disparate images are brought together at high speeds. Photographs from magazines, illustrations and images of the 20th century are combined and animated usually as a satire on American life. What Who How (1955) Astral Man (1958) and Science Friction (1959) are prime examples of this first phase. He began to collect vast amounts of movie material and would then “slice a film off like a sausage”. In the late 1950s he developed a machine for combining live footage and collage animation, which led to films such as Achoo Mr. Keroochev (1959), Skullduggery (1960) and eventually Breathdeath (1964), an anti-war film dedicated to Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin was his most ambitious film so far. He first investigated expanded cinema with Three-Screen-Scene (1958) and after spending 1965 working on a number of loops, he returned to concentrate on multi-screen projection and built the Moviedrome as a dedicated theatre for his multiple “movie murals”. In the late 1960s he was one of the first filmmakers to use computer animation and the newly developing video technology.

BREATHDEATH

Stan Vanderbeek, USA, 1964, 16mm, b/w, sound, 10 min

“A film experiment that deals with the photo reality and the surrealism of life. It is a collage-animation that cuts up photos and newsreel film and reassembles them, producing an image that is a mixture of unexplainable fact (Why is Harpo Marx playing harp in the middle of a battlefield ?) with the inexplicable act (Why is there a battlefield ?). It is a black comedy, a fantasy that mocks death … a parabolic parable.” (Stan Vanderbeek, New York Film-Makers’ Cooperative Catalogue #5, 1971)

Jud Yalkut started to make 8mm films in 1961, but it wasn’t until he became involved with Gerd Stern and the USCO multi-media group that he developed the kinetic style he was to become recognised for. Through the mid to late 1960s USCO collaborated on a pioneering series of sound and light presentations of which Yalkut’s films were an integral part. Diffraction Film (1965) was his first to be shot on 16mm, it was premiered during the Hubbub and We Are All One multi-media touring shows. After moving away from USCO, Yalkut made two seminal happening films – Kusama’s Self-Obliteration (1967) and Aquarian Rushes (1970). Between 1966 and 1972 he worked with the artist Nam June Paik on a number of ground-breaking films and videotapes. He has lectured on film since 1968 and continues to work with video as curator at the Digital Gallery in Dayton, Ohio.

DIFFRACTION FILM

Jud Yalkut, USA, 1965, 16mm, colour, silent, 10 min

“The hot eye of diffraction, multiplicity of variables moving out toward clarity and back: ‘the life force impulse’, a spurt-valve momentum, full of love’s natural forms. Consider what street light, subway lights, signs look like as seen through teleidoscopes sculpted from diamonds. ‘The progression of a trip’; shaken out of whatever you were before; how are you going to get back, I mean, you won’t be in that place again ever … wish for and achieve satori, what the ? So you come back to the physical, and you’re a step further out … up …” (Carol Burge writing about Diffraction Film in Ikon Magazine, late 1960s)

After Yantra, James Whitney started work on Lapis (1963-66) which was again executed by hand, though a computer was used to align the drawings for accurate animation. The film is an amazing cosmic mandala set to an Indian raga. It is startlingly beautiful and the complex patterns on the screen make it hard for us to conceive of the great care that went into its construction. After Lapis, James Whitney rested from filmmaking for some years before beginning work on a trilogy consisting of Dwi-Ja (1976), Wu Ming (1970-77) and Hsiang Sheng (1977).

LAPIS

James Whitney, USA, 1963-66, 16mm, colour, sound, 9 min

“There was a long period of development in which I tried to make exterior imagery more closely related to the inner. I reduced the structural mode to the dot-pattern, which gives a quality which in India is called the Akasha, or ether, a subtle element before creation like the Breath of Brahma, the substance that permeates the universe before it begins to break down into the more finite world. That idea as expressed through the dot-pattern was very appealing to me.” (James Whitney speaking to Gene Youngblood in the book Expanded Cinema, 1970)

Pat O’Neill was a sculptor with a background in the fine arts. He began to pursue film as a sculptural device in By The Sea (1963). His films display a manipulation and colour of images that is mainly achieved during the printing process. 7362 (1965-67) combines footage of an oil pump and a dancing girl, and was the most successful of his early films. His complicated printing techniques were further developed in Runs Good (1971), Saugus Series (1974) and Sidewinder’s Delta (1976). Between 1978 and 1995 O’Neill worked on an epic titled Trouble in the Image.

7362

Pat O’Neill, USA, 1965-67, 16mm, colour, sound, 10 min

“7362 was named after the high-speed emulsion on which it was filmed, emphasising the purely cinematic nature of the piece. O’Neill photographed oil pumps with their rhythmic sexual motions. He photographed geometrical graphic designs on rotating drums or vertical panels, simultaneously moving the camera and moving in and out. The basic vocabulary was transformed at the editing table and in the contact printer, using techniques of high-contrast bas-relief, positive/negative bi-pack printing and image ‘flopping’. a Rorschach-like effect in which the same image is superimposed over itself in reverse polarities, producing a mirror-doubled quality.” (Gene Youngblood in his book Expanded Cinema, 1970)

One of the first artists to combine film with video technology was Scott Bartlett. In his first film, Metanomen (1966), he took black and white cinema technology as far as he felt was possible. The next year he was given access to a TV studio where he made OffOn (1967) and Moon 1969 (1969), two pioneering film and video mixes that won many awards. Throughout the 1970s Bartlett continued to develop his visual style with films including Lovemaking (1970) Serpent (1970) and 1970 (1972). He also made two documentaries as educational aids – Making Serpent (1980) and Making OffOn (1981), in which he reproduced the creation of OffOn with his students at UCLA.

OFFON

Scott Bartlett, USA, 1968, 16mm, colour, sound, 9 min

“In the summer of 1967, Mike MacNamee, Glen McKay and Scott Bartlett met for America’s first electrovideographic jam. Bartlett’s film loops and McKay’s light show liquids were mixed through a video effects bank and the results were filmed by MacNamee directly off the studio monitor with a rented kinetoscope camera. Bartlett edited a portion of this material and then built a soundtrack with the help of Tom DeWitt, who had also supplied many of the original film loops, and Manny Meyer, electronic sound composer. The finished film was called OffOn.” (Canyon Cinema Film / Video Catalogue #7, 1992)

The poet and filmmaker Storm De Hirsch was one of the true pioneers of the New American Cinema. After an initial short abstract film (Journey Around a Zero, 1963) she travelled to Italy to make the feature Goodbye in the Mirror (1964) which depicted “the adventures and illusions of three girls living abroad”. On returning to the USA she became immersed in more personal filmmaking and completed a celebrated mystical trilogy of films known as The Color of Ritual, The Color of Thought (1964-67) which includes Divinations (1964), Peyote Queen (1965) and Shaman, A Tapestry For Sorcerers (1967). In 1968 she made the dual-screen projection film Third Eye Butterfly. In The Tattooed Man (1969), De Hirsch combined abstract and live footage into an amazing and deep masterpiece.

THE TATTOOED MAN

Storm De Hirsch, USA, 1969, 16mm, colour, sound, 35 min

“A major work in terms of style, structure, graphic invention, image manipulation and symbolic ritual. Short, abbreviated dream-like moments, fused together by the tension and dynamics of motion-picture time … Dreamers of the dream, killers of the dream, and movie myth are perhaps what happen when we see movies. Symbolic invention and the theatricalization of dreams and making them literal is, to me, the whole function and purpose of movie-making”. (Stan Vanderbeek speaking on The Tattooed Man at the St. Lawrence University Film Festival)

Tom Chomont has made an astounding number of highly poetic and intensely personal films. Many of his early films, for example Morpheus in Hell (1967), Phases of the Moon (1968) and Love Objects (1971), are self-examining psycho-sexual investigations and usually feature creative techniques such as combining positive/negative footage, mirror printing and superimposition. Oblivion (1969) is an astounding and erotic film which occasionally blossoms into 3D when viewed through filter glasses. In the 1970s Chomont pursued a more formal approach but his films remain highly personal, using celluloid to bridge the gap between the mundane and the mystical.

OBLIVION

Tom Chomont, USA, 1969, 16mm, colour, silent, 5 min

“Oblivion was a diary to a large extent—a diary and a portrait and a confession. I think I shot it on two separate evenings, but it had elements of many of our visits: we would sit and talk; he would smoke; at some point one or both of us would feel aroused—usually he would start to take off his shoes when he wanted to have sex. I felt that this material was highly personal, and I was conscious from the beginning that there had to be some kind of formal side to it. I wanted to give the whole film the feeling of being between sleeping and dreaming, and waking.” (excerpts from Tom Chomont’s discussions with Scott MacDonald in 1980, from the book A Critical Cinema, 1988)

Back to top