Date: 13 October 2001 | Season: Cinema Auricular

CINEMA AURICULAR: CINEMA OF THE EAR

13 October – 21 October 2001

London Barbican Centre & Tate Modern

A season of film and video as part of the ELEKTRONIC festival at the Barbican.

It might seem logical to suppose a historical and natural link between electronic music and abstract or impressionistic films, but there are surprisingly few examples of films that were made in direct collaboration between filmmakers and composers or musicians. However, there is a significant body of films that ‘borrow’ or re-appropriate recordings of contemporary music, and a number of works for which their makers have assembled soundtracks which may, if separated from the visuals, be heard as extraordinary electronic compositions. In such films, electronic, tape music, noise, primitive sampling and musique concrete come together in chaos or harmony to accompany astounding visual constructions.

The film series of the Elektronic festival will present screenings in which the sound and image complement each other on the highest level. It will feature an international selection of historic and contemporary works by Bruce Conner, Malcolm Le Grice, Peter Tscherkassky and others, and a live music and film concert by Phill Niblock. Composers whose unique works may be heard of the soundtracks include Edgar Varese, Christian Fennesz, Terry Riley and Karlheinz Stockhausen.

The series will open with an informal screening in the Barbican Pit Theatre on the afternoon of Saturday 13th October. Between the films, Mark Webber and Gregory Kurcewicz will be playing recordings of rare and wonderful electronic music. Come down to our level and see what you’re in for.

Date: 13 October 2001 | Season: Cinema Auricular

OF SYNTHESIS AND SYNTHETICS

Saturday 13 October 2001, at 3:00pm

London Barbican Pit Theatre

Sounds emanating from the early electro-acoustic studios and the primitive/pioneering synthesisers of Robert Moog and Don Buchla. An informal film screening punctuated by recordings of scarce and wonderful electronic music through the ages played by Mark Webber and Gregory Kurcewicz. Including Mick Jagger’s mind-bending score for Kenneth Anger’s Invocation of My Demon Brother and rare recordings of Varese and Ussachevsky. Come hang out, watch films, listen to music, drink coffee, pretend to stroke your beard (though that’s an entirely inappropriate thing to do).

Note: Where the soundtrack is not by the filmmaker, the composer’s name is in square brackets

William Pye, Reflections, UK, 1972, colour, sound, 17 min

David Ringo, Balconies One, USA, c.1968, b/w, sound, 6 min [Edgar Varese]

Ian Hugo, Aphrodisiac I, USA, 1971, colour, sound, 6 min [David Horowicz]

Adam Beckett, Heavy-Light, USA, 1973, colour, sound, 7 min [Barry Schrader]

Hollis Frampton, Special Effects (Hapax Legomena VII), USA, 1972, b/w, sound, 11 min [Don Buchla & Victor Grauer]

Lloyd Williams, Two Images For A Computer Piece (With Interlude), USA, 1970, b/w, sound, 10 min [Vladimir Ussachevsky]

Ed Emshwiller, Thermogenesis, USA, 1972, colour, sound, 12 min [Robert Moog & Jeff Slotnik]

Tom De Witt, AtmosFear, USA, 1966, colour, sound, 6 min

Kenneth Anger, Invocation Of My Demon Brother, USA, 1969, colour, sound, 11 min [Mick Jagger]

Norman McLaren, Synchromy, Canada, 1971, colour, sound, 7 min

David Rimmer, Migration, Canada, 1969, colour, sound, 12m [Phil Werren]

Date: 14 October 2001 | Season: Cinema Auricular

PHILL NIBLOCK LIVE PERFORMANCE

Sunday 14 October 2001, at 6:15pm

London Barbican Pit Theatre

Intermedia artist Phill Niblock (USA) presents a concert of live and pre-recorded microtonal music with simultaneous triple video projection of sections from his long running Movement of People Working film series, shot in Mexico, Peru, Brasil, and China. Niblock makes thick, loud drones of music, filled with microtones of instrumental timbres that generate a multitude of difference tones in the performance space.

Phill Niblock, Hurdy Hurry (for Hurdy Gurdy)

Phill Niblock, A Y U Live (aka As Yet Untitled) (for Baritone Voice)

Phill Niblock, Guitar Too, For Four (for Electric Guitar)

Phill Niblock, Pan Fried 25 (for Bowed Piano)

Guitar Too, For Four will be augmented by a live electric guitar quartet featuring Jem Finer, Robert P. Lee, Matt Rogalsky and Mark Webber.

Date: 15 October 2001 | Season: Cinema Auricular

TRANSCENDENT POWER: ELECTRONIC ELEVATION AND SYSTEM STIMULATION

Monday 15 October 2001, at 7:30pm

London Barbican Cinema

Going beyond direct experience into the spiritual and ecstatic realms, reaching outwards / inwards / upwards toward perception. Beginning with a film that “plays directly on the mind through programatic stimulation of the central nervous system” and ending with Bruce Conner’s amazing hallucinogenic journey. Rarely seen works by the abstract masters Davis and Belson, plus Kirchhofer’s stunning dematerialization of celluloid and Vegter’s captivating computer piece.

Note: Where the soundtrack is not by the filmmaker, the composer’s name is in square brackets

Standish Lawder, Raindance, 1972, 16 min [Robert Withers]

James Whitney, Yantra, 1950-57, 8 min [Henk Badings]

James Davis, Energies, 1957, 10 min [Norman De Marco]

Patrice Kirchhofer, Densité Optique 1, 1977, 27 min

Daina Krumins, The Divine Miracle, 1973, 5 min [Rhys Chatham]

Bart Vegter, Nacht Licht, 1993, 13 min [Kees van der Knaap]

Jordan Belson, Allures, 1961, 7 min

Bruce Conner, Looking For Mushrooms, 1961/96, 15 min [Terry Riley]

PROGRAMME NOTES

TRANSCENDENT POWER: ELECTRONIC ELEVATION AND SYSTEM STIMULATION

Monday 15 October 2001, at 7:30pm

London Barbican Cinema

RAINDANCE

Standish Lawder, USA, 1972, colour, sound, 16 min [Robert Withers]

Plays directly on the mind through programatic simulation of the central nervous system. Individual frames of film are imprinted on the retina of the eye in a rhythm, sequence and intensity that corresponds to Apha-Wave frequencies of the brain. Becomes an experience of meditative liberation beyond the threshold of visual comprehension. Visions turn inward. The film directs our mental processes, controlling how we think as well as what we see. Images fuse with their after-images, colours arise from retinal release of exhausted nerve endings, forms dance across short-circuited synapses of the mind. Made entirely from a scrap of found footage taken from an old animated cartoon representing a sheet of falling rain. The cartoon was called The History of Cinema.

YANTRA

James Whitney, USA, 1950-57, colour, sound, 8 min [Henk Badings]

The repeated accelerating flickers between black and white or solid colour frames photo-kinetically induce an ‘alpha’ meditative state. Into the climax of these generative alternations of spectral opposites, the dots enter and enact movements which are carefully ‘choreographed’ in the sense of purely visual ‘music’. The screen is scrupulously sustained as a flat expository surface, and a reflexive consciousness of the film material process is maintained by the use of flickers, transparent / white backgrounds, scratches, and solarized, step-printed episodes, in which the hand-wrought, irregular textures also recall James’ expertise as a raku potter and the alchemical processes of transmuting elements, in this case the coloured chemicals of the film emulsion by the ‘solar’ fire. (William Moritz)

ENERGIES

James Davis, USA 1957, colour, sound, 10 min [Norman De Marco]

Just as the musician organises rhythms of sound in order to stimulate imagination and produce an emotional response, so I organise visual rhythms of moving forms of colour. Also like the musician, who doesn’t use the sounds of nature but invented sounds, produced by various instruments, I use invented forms of colour which I produce artificially with brightly coloured transparent plastics. I set them in motion, play light upon them, and film what happens. Obviously, I am not trying to present facts or to tell a story. I am trying to stir the creative imagination of my fellow men.

DENSITÉ OPTIQUE 1

Patrice Kirchhofer, France, 1977, colour, sound, 27 min

This film is an abyss. Abyssus abyssum invocat. A film made of other films. It is deja vu. ‘Déjà vu’ is a general impression of the work. A somewhat melancholic ‘déjà vu’. Adolescence also. A slow rhythm, jerked like a wave, the film makes progress underneath the eyes. Under which eyes? Those of the slow anguish of adolescence. Which one doesn’t resolve, sometimes…

THE DIVINE MIRACLE

Daina Krumins, USA, 1973, colour, sound, 5 min [Rhys Chatham]

An intriguing composite of what looks like animation and pageant-like live action is The Divine Miracle, which treads a delicate line between reverence and spoof as it briefly portrays the agony, death and ascension of Christ in the vividly coloured and heavily outlined style of Catholic devotional postcards, while tiny angels (consisting only of heads and wings) circle like slow mosquitoes about the central figure. Ms. Krumins tells me that no animation is involved, that the entire action was filmed in a studio, and that Christ, the angels and the background were combined in the printing. She also says it took her two years to produce it. (Edgar Daniels)

NACHT LICHT

Bart Vegter, Netherlands, 1993, colour, sound, 13 min [Kees van der Knaap]

A computer-film in three parts. The images consist of 8 to 14 independent elements. Each part has its own, formal starting-point. On this formal basis, variations are executed by gradual changes in position, direction, movement, velocity and colour of the elements. After making four animated abstract films ‘by hand’, this is my first film made with a computer. The formal approach that I use generally in making films proved to be very suitable for the way a computer works and can be programmed. This brought me to writing image- generating programs in computer-language, of which Nacht-Licht is the first result as film. The way I make films can be compared to building a “machine” which produces images. This machine consists of the working-principle: the system I choose to generate the images. In this manner series of images are generated, determined by (1) the machine, and (2) the data I put into it.

ALLURES

Jordan Belson, USA, 1961, colour, sound, 7 min

I think of Allures as a combination of molecular structures and astronomical events mixed with subconscious and subjective phenomena – all happening simultaneously. The beginning is almost purely sensual, the end perhaps totally nonmaterial. It seems to move from matter to spirit in some way. Oskar Fischinger had been experimenting with spatial dimensions, but Allures seemed to be outer space rather than earth space. After working with some very sophisticated equipment in the Vortex Concerts, I learned the effectiveness of something as simple as fading in and out very slowly.

LOOKING FOR MUSHROOMS

Bruce Conner, USA, 1961/96, colour, sound, 15 min [Terry Riley]

Looking For Mushrooms unfolds at one and the same time as a hyperactive, realistic recording – a travel diary – and as a freewheeling, almost hallucinatory spectacle. The arc of the film’s structure suggests a shift from the material world shown in great detail to a purely ideational realm of art. What reconciles these seemingly contradictory zones is Conner’s mediating sensibility … In 1995, Conner revised Looking For Mushrooms, [which was] step-printed and slowed down by a factor of five, and given a new score. The film gained a heightened level of visibility through a pacing that restrained the abstracting speed of the original shooting, cutting, and superimposition; and it acquired a potent acoustic counterpoint through the addition of a performance by Terry Riley that highlights the microrhythms of Conner’s masterful camera work and complex montage. (Bruce Jenkins)

Back to top

Date: 16 October 2001 | Season: Cinema Auricular

CURRENTS OF CHAOS: ELECTRO-SHOCK CINEMA

Tuesday 16 October 2001, at 6:15pm

London Barbican Cinema

Confusion … delusion … retribution. Electronic feel flows as your nervous system careens into overdrive. From the chaotic Outer Space to the sublime #11, five films plugged directly into the National Grid to give maximum audio-visual pleasure (or pain). Throbbing, shouting, screaming, smashing … This is not for the faint-hearted, but what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.

Note: Where the soundtrack is not by the filmmaker, the composer’s name is in square brackets

Peter Tscherkassky, Outer Space, 1999, 10 min

Hollis Frampton, Critical Mass, 1971, 25 min

Martin Arnold, pièce touchée, 1989, 15 min

Paul Sharits, Axiomatic Granularity, 1972-73, 20 min

Joost Rekveld, #11 (Marey<->Moiré), 1999, 21 min [Edwin van der Heide]

PROGRAMME NOTES

CURRENTS OF CHAOS: ELECTRO-SHOCK CINEMA

Tuesday 16 October 2001, at 6:15pm

London Barbican Cinema

OUTER SPACE

Peter Tscherkassky, Austria, 1999, b/w, sound, 10 min

A woman, terrorised by an invisible and aggressive force, is also exposed to the audience’s gaze, a prisoner in two senses. Outer Space agitates this construction, which is prototypical for gender hierarchies and classic cinema’s viewing regime, and allows the protagonist to turn them upside down. Flickering images, everything crashes, explodes; perforations and the soundtrack are engaged in a violent struggle. The story ends in the woman’s resistant gaze. (Isabella Reicher)

CRITICAL MASS

Hollis Frampton, Critical Mass, USA, 1971, b/w, sound, 25 min

As a work of art I think Critical Mass is quite universal and deals with all quarrels (those between men and women, or men and men, or women and women, or children, or war). It is war!…It is one of the most delicate and clear statements of inter-human relationships and the difficulties of them that I have ever seen. It is very funny, and rather obviously so. It is a magic film in that you can enjoy it, with greater and greater appreciation, each time you look at it. Most aesthetic experiences are not enjoyable on the surface. You have to look at them a number of times before you are able to fully enjoy them, but this one stands up at once, and again and again, and is amazingly clear. (Stan Brakhage)

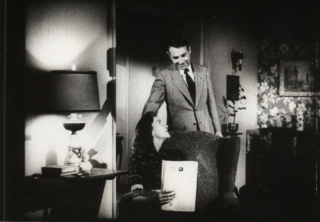

pièce touchée

Martin Arnold, Austria, 1989, b/w, sound, 15 min

While Muybridge seems to have believed his photographs analysed the motion of ‘reality’ Arnold is well aware that piéce touchée explores a Hollywood cliché that is, at most, only a pretence of reality: a cinematic gesture that polemicises a culturally approved relationship between the genders. Arnold uses his optical printer to lay bare the gender-political implications of the husband’s arrival and to transform this gesture, which has become nearly invisible to most viewers, into a phantasmagoria of visual effects that would make any trick-film director proud. (Scott MacDonald)

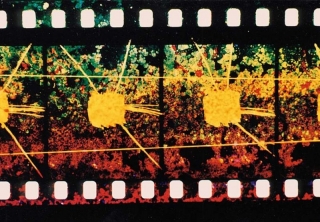

AXIOMATIC GRANULARITY

Paul Sharits, USA, 1972-73, colour, sound, 20 min

In Spring 1972 a series of analyses of colour emulsion ‘grain’ imagery was undertaken (the word ‘imagery: is significant because only representations of light sensitive crystals, or ‘grain’, remain on a developed roll of colour film). The investigation is preliminary to the shooting of Section 1 of “Re: Re: Projection”, Variable Emulsion Density, wherein attempts to construct convincing lap dissolves of solid colour fields with straight fine grain Ektachrome ECO proved unsatisfactory. It was thought that more ‘grainy’ colour field interactions might adequately prevent the undesirable smoothness of hue mixture resulting from ECO superimposition. A discreteness of individual hues, during superimposition, is necessary; then, a switch to Ektachrome EF, pushed extra stops in development, seemed somewhat reasonable. Still, unexpected (colour blurring) problems arose and it was clear that a ‘blow up’ of the situation was called for; a set of primary principles was needed and, particle by particle, Axiomatic Granularity seemed to formulate itself. Its ‘structure’ lacks normative ‘expressive intentionality’.

#11 (MAREY<->MOIRÉ)

Joost Rekveld, Netherlands, 1999, colour, sound, 21 min [Edwin van der Heide]

A film in which all images were generated by intermittently recording the movement of a line. It is a film about the discontinuity that lies at the heart of the film medium. After making films #3 and #5 I was thinking about other methods to generate images by distributing light across film frames in perverted ways. One idea that came to mind was to record a continuous movement with long exposures like I had been doing before, but to interrupt these exposures many times to generate visual patterns. This would create interesting interferences between the motions involved. The other development was my increasing interest in the technological history of film. I had been looking for a kind of ‘pure’ film: images the film apparatus would come up with if left alone, as it were. While thinking about ‘pure’ film I started to look towards the historic origins of film and new media in general. Besides “#11” this led to experiments I did with various mechanical installations using nipkow discs or anorthoscopes. In order to make the film I constructed a machine with the help of which I was able control three movements: the movement of the film in the camera , the rotation of a shutter in front of the lightsource, and the movement of a line in front of the camera. The interferences possible between these three motions are the material I used to compose #11. For every section of the film I recorded a set of high contrast black and white originals which I used in the optical printer to create interference images in colour.

Back to top

Date: 17 October 2001 | Season: Cinema Auricular

NEW AGE VOLTAGE: CONTEMPORARY DIGITAL SOUND AND VISION

Wednesday 17 October 2001, at 6:00pm

London Barbican Prompt Corner

The sounds of the analogue versus the digital, burning a cathode ray hole direct through your retina. A video programme of recent audio-visions from Vienna and other painfully modern assemblages from UK, France and Canada. Having broken sound and image down to its constituent blips and pixels, these contemporary filmmakers are reconstructing matter in beguiling new ways.

Note: Where the soundtrack is not by the filmmaker, the composer’s name is in square brackets

Billy Roisz & Dieter Kovacic, smokfraqs, 2001, 4 min

Steven Ball, Sevenths Synthesis, 2001, 7 min

Myriam Bessette, Azur, 2001, 3 min

Jurgen Moritz, Instrument, 1997, 5 min [Christian Fennesz]

Ben Pointeker, Overfart, 1999, 6 min [General Magic]

Nicolas Berthelot, Chrominances, 2000, 6 min

ReMI, comp.tot4: Zarakesh, 1999, 10 min [Renata Oblak]

[n:ja], track 09, 2001, 4 min [Shabotinski]

Herwig Weiser, Entrée, 1999, 9 min

Michaela Schwentner, Transistor, 2000, 6 min [Radian]

Karoe Goldt, ILOX, 2001, 3 min [Rashim]

PROGRAMME NOTES

NEW AGE VOLTAGE: CONTEMPORARY DIGITAL SOUND AND VISION

Wednesday 17 October 2001, at 6:00pm

London Barbican Prompt Corner

smokfraqs

Billy Roisz & Dieter Kovacic, Austria, 2001, colour, sound, 4 min

Distorted geometric forms are used to create a type of grainy texture, or a flickering background of subdued coloration in front of which white particles dance. Frames are repeated into infinity and a drop meanders across the finely grained strip. Eight 30-second sequences punctuated by black frames: smokfraqs, a serial work, is made compelling in part by its structural clarity and formal simplicity. (Isabella Reicher)

SEVENTHS SYNTHESIS

Steven Ball, UK, 2001, colour, sound, 7 min

Animated abstracted synthetic sound-to-image/image-to-sound digital material parsing experiments collide with trad pagan Beltane folk dance remixed Seven Step Polka in fragmentary, fractured fast digital scratch mix.

AZUR

Myriam Bessette, Canada, 2001, colour, sound, 3 min

Composed of synthetic light and voice samples, Azur attempts to establish an emotional link with the spectator.

INSTRUMENT

Jurgen Moritz, Austria, 1997, colour, sound, 5 min [Christian Fennesz]

Instrument is reminiscent of found footage shot a long time ago: six seconds of a girl moving. Moritz calls it ‘six seconds of innocence’. He manipulated the material until only fragments of this innocence remained. To the pumping rhythmn of the music the girl is simultaneously present and absent, never totally present. Moritz makes her intangible and thus creates space for ones own fantasy. (Lies Holtrop)

OVERFART

Ben Pointeker, Austria, 1999, colour, sound, 6 min [General Magic]

Inspired by the filmmaker’s interest in early Romantic landscape painting, especially the works of Caspar David Friedrich. Though “Temko” by General Magic is virtually the sole element of the soundtrack, this work was not intended to be a music video. The abstract spatiality of the music, which was apparently set in contrast to the images, and their cycles complement one another to produce the same intangibility.

CHROMINANCES

Nicolas Berthelot, France, 2000, colour, sound, 6 min

I believe that each image is creative of music and that each sound is a creator of images, and the two entities are independent of each other. Chrominances is built like a conversation between visual and musical reasoning. A new dialogue is born, a dialogue which neither visual, nor aural. It is a dialogue which binds the audio-visual spectator with the object, a dialogue which is not imposed, an original dialogue on each vision, each hearing. I tried to make a creative film of freedom, where the eyes and the ears would be two dancers who always dance together for the first time.

comp.tot4: ZARAKESH

ReMI, Austria, 1999, colour, sound, 10 min [Renata Oblak]

During a transmission, a video recording was damaged by defective equipment to the extent that none of the original concrete elements were visible. The fragments remaining from the process of decomposition were fed into a defective computer system, and a camera was able to capture only a portion of the stream of information. The result: the originally concrete footage was reorganised in a different aesthetic context through these limitations.

track 09

[n:ja], Austria, 2001, colour, sound, 4 min [Shabotinski]

A lively game with spatial structures. The constant modulation of scales and the resulting shifts in the grid’s spaces provide glimpses into ‘microscopic’ spaces.

ENTRÉE

Herwig Weiser, Austria, 1999, b/w, sound, 9 min

A reflection on the fusion of viewer and visual world in hi-tech cinema locations. The raw stock of the videotape is grainy film footage shot in the Parc d’image in Poitiers: the spherical crystalloid monumental architecture on green fields, oversize screens and dark arenas reserved for audiences. Multiple visual echoes, double images and the industrial staccato of sound samples on the soundtrack represent the technical subsumation of people subjected to the dictate of a robot-controlled event that consigns the viewers, unconsciously, from one experimental world to the next, and causes them ultimately to vanish in the process. (Reinhard Wolf)

TRANSISTOR

Michaela Schwentner, Austria, 2000, colour, sound, 6 min [Radian]

Accompanied by short, choppy segments of noise fragments, geometric gridworks appear with equal abruptness, as in a visual staccato. This not only places a visual matrix underneath the rasping, eruptive sound as a foundation, it also reveals the underlying matrix-like quality, the locking function in the digital culture as the interface at which graphic and acoustic elements have always overlapped. (Christian Höller)

ILOX

Karoe Goldt, 2001, Austria, colour, sound, 3 min [Rashim]

In a barely noticeable way, vertical strips with shades of red move intermittently to the rhythmically snapping and crackling soundtrack by Rashim (Yasmina Haddad and Gina Hell). The vague shadow of a twig appears through the strips of colour. The work uses this radical reduction to create an enormous amount of tension. To achieve this result, Karo Goldt animated over two thousand digitally manipulated photographs of a red, leafless plant called ilox. The influence of Colour Field painters such as Mark Rothko and Ad Reinhardt on the filmmaker is obvious, whose work in this medium followed her involvement with painting and photography. (Norbert Pfaffenbichler)

Back to top

Date: 17 October 2001 | Season: Cinema Auricular

SEEING SOUND: LIGHTNING STRIKES THE OPTIC NERVE

Wednesday 17 October 2001, at 7:30pm

London Barbican Cinema

Optical sound on 16mm film – a lightbulb reads a strip of amorphous black emulsion on clear celluloid and it somehow makes sound sense. Since the 1930s artists have examined and exploited the possibilities of drawing or printing a soundtrack. Two senses combined and confounded, both musical and cacophonous. Can you see what you hear?

Oskar Fischinger, Ornament Sound, 1932, 7 min

Norman McLaren, Dots (Points), 1948, 3 min

Barry Spinello, Soundtrack, 1969, 10 min

Richard Reeves, Linear Dreams, 1997, 7 min

Pierre Rovere, Black and Light, 1974, 8 min

Lis Rhodes, Dresden Dynamo, 1974, 5 min

Chris Garrett, Exit Right, 1976, 3 min

Jun’ichi Okuyama, My Movie Melodies, 1980, 7 min

Guy Sherwin, Musical Stairs, 1977, 10 min

Peter Tscherkassky, L’Arrivée, 1998, 3 min

Taka Iimura, Shutter, 1971, 22 min

Screening introduced by filmmaker Guy Sherwin.

PROGRAMME NOTES

SEEING SOUND: LIGHTNING STRIKES THE OPTIC NERVE

Wednesday 17 October 2001, at 7:30pm

London Barbican Cinema

ORNAMENT SOUND

Oskar Fischinger, Germany, 1932, b/w, sound, 7 min

‘You ear what you see, you see what you ear’. Indeed, on the left side of the image, unravelling vertically, is the synchronised drawing of the sound wave that is heard. Along the drawing of these sound waves moving small rectangles with appear each new sound level, indicating the height of the note produced in conventional notation, for example C#4 for ‘Do #’ in the fourth octave on the piano. Tönnende Ornamente thus presents the spectral range of the synthetic sound to us. At the beginning of film a falling scale explores the low register, followed by a perambulation of an octave in the acute part of the sound spectrum. Fischinger also presents the various stamps and types of attack which one can obtain with the optical sounds. (Philippe Langlois)

DOTS (POINTS)

Norman McLaren, Dots (Points), Canada, 1948, colour, sound, 3 min

This film of geometric abstractions drawn directly on the film with pen and ink was made independently by McLaren. Exploring the synchronisation of the visuals with a synthetic soundtrack, McLaren drew a percussive rhythm of clicking sounds along the edge of the film. The soundtrack reveals how early in his career McLaren achieved a sophistication in the use of this method. The music ranges over several octaves, integrating perfectly with the moving blue and white dots that flip across the screen on a red background. (Maynard Collins)

SOUNDTRACK

Barry Spinello, Soundtrack, USA, 1969, b/w & colour, sound, 10 min

John Cage wrote, in 1938, of a “new electronic music” to be developed out of the photoelectric cell optical-sound process used in films. Any image – his example is a picture of Beethoven – or mark on the soundtrack, successively repeated, will produce a distinct pitch and timbre. This new music, he said, would be built along the lines of film, with the basic unit if rhythm logically being the frame. However, with the subsequent development of magnetic tape a few years later (and the advantages it has in convenience, speed, capacity to record, erase and playback live sound), the filmic development of electronic music initially envisioned by Cage was obscured. Had magnetic record tape never been invented, undoubtedly a rich new music would have developed via optical sound means, and composers would have found ways to work with film.

LINEAR DREAMS

Richard Reeves, Canada, 1997, colour, sound, 7 min

In Linear Dreams, Richard Reeves explores new realms of the imagination. The piece begins with a line pulsing to a heartbeat -the base for all living things. Images then explode and implode until they are released from the human form, expand outward over a vast mountain range, and then return to their origin. Reeves’ hand-drawn soundtrack underscores Linear Dreams, creating a multiple award-winning piece filled with rhythmic electricity.

BLACK AND LIGHT

Pierre Rovere, Black and Light, France, 1974, b/w, sound, 8 min

This film was directly executed on computer without cinematographic intervention or equipment. It is not the communication of a movement, but a succession of facts made up that the device of projection translated for us into impressions of movements. This film does not refer to an external reality, but wants to be its own reality.

DRESDEN DYNAMO

Lis Rhodes, UK, 1974, colour, sound, 5 min

The result of experiments with the application of Letraset and Letratone onto clear film. It is essentially about how graphic images create their own sound by extending into that area of film which is ‘read’ by optical sound equipment. The final print has been achieved through three separate, consecutive printings from the original material, on a contact printer. Colour was added with filters on the final run. The film is not a sequential piece. It does not develop crescendos. It creates the illusion of spatial depth from essentially flat, graphic, raw material. (Tim Bruce)

EXIT RIGHT

Chris Garrett, Exit Right, UK, 1976, b/w, sound, 3 min

A one second shot of me walking into the shot wearing a striped jersey was printed repeatedly. This strip of negative was moved laterally across the printer every ten seconds of film time, so that the image of the piece of film material, containing its figurative image moves into the projected frame from the left, across the frame and out across the optical soundtrack area to the right. Featuring a new line in Musical Pullovers.

MY MOVIE MELODIES

Jun’ichi Okuyama, Japan, 1980, b/w, sound, 7 min

In this film, the image produces the sound, and the sound is the image. It catches sight of landscapes and incidents. The various images are used to cover an extensive range of sounds. The principal melody is a radiograph of a comb.

MUSICAL STAIRS

Guy Sherwin, UK, 1977, b/w, sound, 10 min

I shot the images of a staircase specifically for the range of sounds they would produce. I used a fixed lens to film from a fixed position at the bottom of the stairs. Tilting the camera up increases the number of steps that are included in the frame. The more steps that are included in the frame the higher the pitch of sound. A simple procedure gave rise to a musical scale (in eleven steps) which is based on the laws of visual perspective. A range of volume is introduced by varying the exposure. The darker the image the louder the sound (it can be the other way round but Musical Stairs uses a soundtrack made from the negative of the picture). The fact that the staircase is neither a synthetic image, nor a particularly clean one (there happened to be leaves on the stairs when I shot the film) means that the sound is not pure, but dense with strange harmonies.

L’ARRIVÉE

Peter Tscherkassky, Austria, 1998, b/w, sound, 3 min

Just as the record player needle has to find the right groove, “L’Arrive” has to settle into the perforation tracks before the narrative line can develop. A train arrives in a station where a hand-instigated collision with another train takes place. The event is not just a depiction, but a battle of the material itself. This is not the end, but the transition to a kiss, the Happy End. L’Arrive demonstrates where cinema begins – with the spectacular, and where it ends – with intimacy. (Bert Rebhandl)

SHUTTER

Taka Iimura, 1971, Japan, b/w, sound, 22 min

Using two projector speeds and various camera speeds, Iimura photographed the light thrown onto a screen by a projector with no film running through it. Because of the disparities between the speeds of the camera and projector shutters, the resulting footage, which he printed first in positive, then in negative, creates a series of flicker effects. One of the more interesting of those many works which have attempted to explore the visual potential of film process and materials. (Scott MacDonald)

Back to top

Date: 18 October 2001 | Season: Cinema Auricular

OHM TAPING: TAPE COMPOSITIONS & MUSIQUE CONCRETE

Thursday 18 October 2001, at 7:30pm

London Barbican Cinema

Before the sampler: the tape machine. Before the break-beat: the tape loop. Before plunderphonics: musique concrete. Going back to a time when it was inventive and original to play with and re-appropriate snatches of sound gathered from disparate sources. Pre post-modernism from pre-eminent filmmakers.

Note: Where the soundtrack is not by the filmmaker, the composer’s name is in square brackets

Malcolm Le Grice, Threshold, 1972, 10 min

Keewatin Dewdney, The Maltese Cross Movement, 1967, 8 min [The Beach Boys]

Carolee Schneemann, Viet Flakes, 1965, 9 min [James Tenney]

John Schofill , Xfilm, 1966-68, 14 min [William Moraldo]

Stan Brakhage, I … Dreaming, 1988, 7 min [Joel Haertling]

Jud Yalkut & Nam Jun Paik, Beatles Electroniques, 1966-69, 3 min [Kenneth Werner]

JJ Murphy, Ice, 1972, 7 min

Ivan Zulueta, Masaje, 1972, 3 min

Jeff Keen, Marvo Movie, 1967, 5 min [Bob Cobbing]

Robert Breer, Fist Fight, 1964, 9 min [Karlheinz Stockhausen]

Eino Ruutsalo, Kaksi Kanaa, 1963, 4 min [Erkki Kurenniemi]

Jud Yalkut, Turn Turn Turn, 1965-66, 10 min [The Byrds]

PROGRAMME NOTES

OHM TAPING: TAPE COMPOSITIONS & MUSIQUE CONCRETE

Thursday 18 October 2001, at 7:30pm

London Barbican Cinema

THRESHOLD

Malcolm Le Grice, UK, 1972, colour, sound, 10 min

Le Grice no longer simply uses the optical printer as a reflexive mechanism, but utilises the possibilities of colour-shift and permutation of imagery as the film progresses from simplicity to complexity. The initial use of pure red and green filters gives way to a broad variety of colours and the introduction of strips of coloured celluloid which are drawn through the printer and begins to build an image which becomes graphically and spatially complex – if still abstract – and which evokes the paintings of, say, Clifford Still or Morris Louis. With the film’s culmination in representational, photographic imagery, one would anticipate a culminating ‘richness’ of image; yet the insistent evidence of splice bars and the loop and repetition of the short piece of found footage and the conflicting superimposition of filtered loops all reiterate the work which is necessary to decipher that cinematic image. (Deke Dusinberre)

THE MALTESE CROSS MOVEMENT

Keewatin Dewdney, Canada, 1967, colour, sound, 8 min [The Beach Boys]

The film reflects Dewdney’s conviction that, “the projector, not the camera, is the filmmaker’s true medium”. The form and content of the film are shown to derive directly from the mechanical operation of the projector – specifically the animation of the disk and the cross illustrates graphically (no pun intended) the projector’s essential parts and movements. It also alludes to a dialectic of continuous-discontinuous movements that pervades the apparatus, from its central mechanical operation to the spectator’s perception of the film’s images … His soundtrack demonstrates that what we hear is also built out of continuous-discontinuous ‘sub-sets’. The film is organised around the principle that it can only complete itself when enough separate and discontinuous sounds have been stored up to provide the male voice on the soundtrack with the sounds needed to repeat a little girl’s poem; “The cross revolves at sunset / The moon returns at dawn / If you die tonight / Tomorrow you’re gone.” (William C. Wees)

VIET FLAKES

Carolee Schneemann, USA, 1965, b/w, sound, 9 min [James Tenney]

Composed from an obsessive collection of Vietnam atrocity images I collected from foreign magazines and newspapers over a five-year period. Magnifying glasses from the ‘five and dime’ were taped onto a borrowed 16mm Bolex in order to physically ‘travel’ within the photographs – producing a rough animation. Images in and out of focus, broken rhythms and pans, the abstracted shapes and motions, speeding perceptual contradictions. For instance, a pointillism of falling black specks in focus becomes bombs dropping through the sky; and impressionistic swirl of tones translates as faces of US soldiers leading barefoot villagers from a gas-filled tunnel; a “Rembrandt ink drawing” focuses in as a tank dragging a roped body… James Tenney’s sound collage intercuts three-second fragments of Vietnamese religious chants and secular songs with fragments of Bach and 1960s ‘Top of the Charts’.

XFILM

John Schofill, USA, 1966-68, colour, sound, 14 min [William Moraldo]

Through precise manipulation of individual frames and groups of frames, Schofill creates an overwhelming sense of momentum practically unequalled in synaesthetic cinema. There is almost a visceral, tactile impact to these images, which plunge across the field of vision like a dynamo. (Gene Youngblood)

I … DREAMING

Stan Brakhage, USA, 1988, colour, sound, 7 min [Joel Haertling]

A setting-to-film of a ‘collage’ of Stephen Foster phrases by composer Joel Haertling. The recurring musical themes and melancholia of Foster refer to ‘loss of love’ in the popular ‘torch song’ mode; but the film envisions a re-awakening of such senses-of-love as children know, and it posits (along a line of words scratched over picture) the psychology of waiting.

BEATLES ELECTRONIQUES

Jud Yalkut & Nam Jun Paik, USA, 1966-69, colour, sound, 3 min [Kenneth Werner]

Shot in black and white from a live broadcast of the Beatles while Paik electromagnetically improvised distortions on the receiver, and also from videotapes material produced during a series of experiments with filming off the monitor of a Sony videotape recorder. The film is three minutes long and is accompanied by an electronic soundtrack by composer Ken Werner, called “Four Loops”, derived from four electronically altered loops of Beatles sound material. The result is an eerie portrait of the Beatles not as pop stars, but rather as entities that exist solely in the world of electronic media. (Gene Youngblood)

ICE

JJ Murphy, USA, 1972, colour, sound, 7 min

To make Ice Murphy projected Franklin Miller’s film Whose Circumference is Nowhere onto one side of a block of ice and recorded what one could see through the ice from the opposite side, in a single continuous take. The soundtrack is a tape recorder recording under water. The result is a transformation of Miller’s film into an abstract experience of a very different kind. (Scott MacDonald)

MASAJE

Ivan Zulueta, Spain, 1972, b/w, sound, 3 min

Using the technique of direct photography off the TV screen, he composes three minutes “in which we see, speeded up, the complete television programming on a day of union and military parades. There was a subliminal Franco, and we didn’t even submit it to the censors…” The soundtrack alternates effects, noises and sounds of all kinds. The result is a really frenetic visual ‘massage’ that exposes the viewer’s eye to fleeting movie images, ads and news reports in rapid-fire succession. (Carlos F. Heredero)

MARVO MOVIE

Jeff Keen, 1967, UK, colour, sound, 5 min [Bob Cobbing]

Movie wizard initiates shatter brain experiment Eeeow! – the fastest movie firm alive – at 24 or 16fps even the mind trembles – splice up sequence two – flix unlimited, an inside yr very head the images explode – last years models new houses and such terrific death scenes while the time and space operator attacks the brain via the optic nerve – will the operation succeed – will the white saint reach in time the staircase now alive with blood – only time will tell says the movie master – meanwhile deep inside the space museum… (Ray Durgnat)

FIST FIGHT

Robert Breer, Fist Fight, USA, 1964, colour, sound 9 min [Karlheinz Stockhausen]

The film articulates separated by sections of blackness. In each burst a technique or series of images may dominate or provide a matrix, but all the elements (photographs, cartoons, abstractions) occur in each cluster. The serial structure is reinforced by the soundtrack. The filmmaker had completed the silent editing for a premiere presentation as part of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s event “Originale”, in New York in 1964. The soundtrack was initially recorded during the performances of the event, including the film’s projection. Breer then composed bursts of audience noise, music, and nearly quiet backgrounds in relationship to the images. (P. Adams Sitney)

KAKSI KANAA

Eino Ruutsalo, Finland 1963, colour, sound, 4 min [Erkki Kurenniemi]

According to Ruutsalo himself, Kaksi kanaa (1963) was composed spontaneously out of throwaway footage. It features a hysterical cavalcade of female nudity, oppressed screen tests, crackers, a floating feather plus an overdose of paint and colour. The soundtrack is a refined electro-acoustical tape collage made by composer Otto Donner. This score, mostly played on Erkki Kurenniemi’s home-built electronic instruments, is a forgotten peak moment of Finnish film music. Kaksi Kanaa is cinematic action painting, and in its condensed expression perhaps Ruutsalo’s most original and permanent masterpiece. (Mika Taanila)

TURN TURN TURN

Jud Yalkut, USA, 1965-66, colour, sound, 10 min [The Byrds]

A film of the eye-shattering, flashing, rotating light sculptures programmed by USCO to turn turn turn the popular song into a rich electronic fugue on the word NOW: Let’s take the OW out of NOW, let’s take the NO out of NOW. (Film Quarterly)

Back to top

Date: 21 October 2001 | Season: Cinema Auricular

LA REGION CENTRALE

Sunday 21 October 2001, at 3:00pm

London Tate Modern

Snow’s mammoth endeavour. Three hours of continuous swooping, swirling, twisting pans over a desolate Canadian landscape. The remote tonal instructions to the camera provoked an inspired minimal (maximal) soundtrack. Hold on to your hats, this trip may take some time.

Michael Snow, La Region Centrale, Canada, 1970-71, colour, sound, 190 min

Special off-site screening related to the “Cinema Auricular” programme at the Barbican Cinema.