Date: 1 May 2002 | Season: Shoot Shoot Shoot 2002 | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT: THE FIRST DECADE OF THE LONDON FILM-MAKERS’ COOPERATIVE & BRITISH AVANT-GARDE FILM 1966-76

3 May–28 May 2002

London Tate Modern

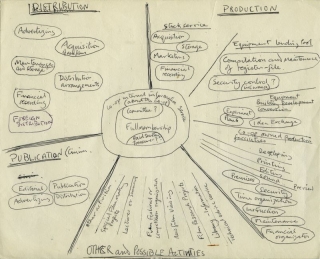

The London Film-Makers’ Co-operative was founded in 1966 and based upon the artist-led distribution centre created by Jonas Mekas and the New American Cinema Group. Both had a policy of open membership, accepting all submissions without judgement, but the LFMC was unique in incorporating the three key aspects of artist filmmaking: production, distribution and exhibition within a single facility.

Early pioneers like Len Lye, Antony Balch, Margaret Tait and John Latham had already made remarkable personal films in Britain, but by the mid-60s interest in “underground” film was growing. On his arrival from New York, Stephen Dwoskin demonstrated and encouraged the possibilities of experimental filmmaking and the Co-op soon became a dynamic centre for the discussion, production and presentation of avant-garde film. Several key figures such as Peter Gidal, Malcolm Le Grice, John Smith and Chris Welsby went onto become internationally celebrated. Many others, like Annabel Nicolson and the fiercely autonomous and prolific Jeff Keen, worked across the boundaries between film and performance and remain relatively unknown, or at least unseen.

The Co-op asserted the significance of the British films in line with international developments, whilst surviving hand-to-mouth in a series of run down buildings. The physical hardship of the organisation’s struggle contributed to the rigorous, formal nature of films produced during this period. While the Structural approach dominated, informing both the interior and landscape tendencies, the British filmmakers also made significant innovations with multi-screen films and expanded cinema events, producing works whose essence was defined by their ephemerality. Many of the works fell into the netherworld between film and fine art, never really seeming at home in either cinema or gallery spaces.

“What follows is a set of instructions, necessarily incomplete, for the construction, necessarily impossible, of a mosaic. Each instruction must lead to the screen, the tomb and temple in which the mosaic grows. The instructions are fractured but not frivolous. They are no more than clues to the films which lust for freedom and re-illumination with, by and of the cinema. What follows is not truth, only evidence. The explanation is in the projection and the perception.” —Simon Hartog, 1968

“It is often difficult for a venue organiser/programmer to determine from written description what an individual or group of film-makers work is ‘about’, from where it comes, to what or whom it is addressing itself. Equally, it is difficult for a film-maker to provide such information from within the pages of a catalogue when for many, including myself, the entire project or the area into which one’s work energy is concentrated, is intent on clarifying these kind of questions. The films outside of such a situation become more or less dead objects, the residue (though hopefully a determined residue) of such an all-embracing pursuit.” —Mike Leggett, 1980

“The most important thing still is to let oneself get into the film one is watching, to stop fighting it, to stop feeling the need to object during the process of experience, or rather, to object, fight it, but overcome each moment again, to keep letting oneself overcome one’s difficulties, to then slide into it (one can always demolish the experience afterwards anyway, so what’s the hurry?).” —Peter Gidal, c.1970-71

Shoot Shoot Shoot, a major retrospective programme and research project, will bring these extraordinary works back to life.

Curated by Mark Webber with assistance from Gregory Kurcewicz and Ben Cook.

Shoot Shoot Shoot is a LUX project. Funded by the Arts Council of England National Touring Programme, the British Council, BFI and the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation.

Date: 1 May 2002 | Season: Infinite Projection | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

JEFF KEEN

Wednesday 1 May 2002, at 7:30pm

London The Photographers’ Gallery

A special Mayday Rayday expanded cinema performance to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the first Rayday broadsheet. Using 8mm, 16mm and video, Jeff Keen bridges the gap between 1969’s Raydayfilm and his recent Artwar: The Last Frontier. A unique and spontaneous mixed-media collage from Britain’s first and most productive independent filmmaker.

Jeff Keen, From Raydayfilm to Artwar, UK, 1969-2002, colours, sounds, c.70 min (multi-media performance)

“Keen is indebted to the Surrealist tradition for many of his central concerns: his passion for instability, his sense of le merveilleux, his fondness for analogies and puns, his preference for ‘lowbrow’ art over aestheticism of any kind, his dedication to collage and le hazard objectif. But this ‘continental’ facet of his work – virtually unique in this country – co-exists with various typically English characteristics, which betray other roots. The tacky glamour/true beauty of his Family Star productions is at least as close to the end of Brighton pier as it is to Hollywood B-movies… The heroic absurdity and adult infantilism that are the mainsprings of his comedy draw on a long tradition of post-Victorian humour: not the ‘innocent’ vulgarity of music hall, but the anarchicness of The Goons and the self-lacerating ironies of the 30s clowns, complete with their undertow of melancholia.” (Tony Rayns, “Born to Kill: Mr. Soft Eliminator”, Afterimage No. 6, 1976)

This event is related to the Shoot Shoot Shoot season at Tate Modern throughout May 2002.

Back to top

Date: 3 May 2002 | Season: Shoot Shoot Shoot 2002 | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

EXPANDED CINEMA

Friday 3 May 2002, at 7:30pm

London Tate Modern Level 7 East

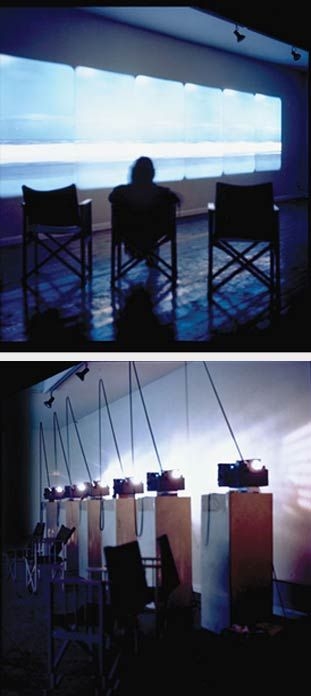

British filmmakers led a drive beyond the screen and the theatre, and their innovations in expanded cinema inevitably took the work into galleries. After questioning the role of the spectator, they began to examine the light beam, its volume and presence in the room.

Malcolm Le Grice, Castle One, 1966, b/w, sound, 20 min

William Raban, Take Measure, 1973, colour, silent, 2 min

William Raban, Diagonal, 1973, colour, sound, 6 min

Gill Eatherley, Hand Grenade, 1971, colour, sound, 8 min

Lis Rhodes, Light Music, 1975-77, b/w, sound, 20 min

Anthony McCall, Line Describing A Cone, 1973, b/w, silent, 30 min

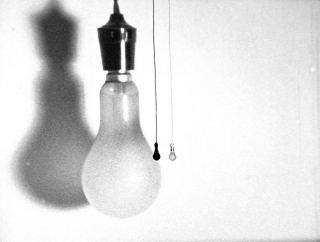

In a step towards later complex projection pieces, for Castle One, Malcolm Le Grice hung a light bulb in front of the screen. Its intermittent flashing bleaches out the image, illuminates the audience and lays bare the conditions of the traditional screening arrangement. Take Measure, by William Raban, visually measures a dimension of the space as the filmstrip is physically stretched between projector and screen. To make Diagonal, he directly filmed into the projector gate and presents the same flickering footage in dialogue across three screens in an oblique formation. Gill Eatherley literally painted in light over extremely long exposures to shoot Hand Grenade, which runs three different edits of the material side-by-side. Light Music developed into a series of enquiries into the nature of optical soundtracks and their direct relation to the abstract image. The film can be shown in different configurations, with projectors side-by-side or facing into each other. Anthony McCall succinctly demonstrates the sculptural potential of film as a single ray of light, incidentally tracing a circle on the screen, is perceived as a conical line emanating from the projector. The beam is given physical volume in the room by use of theatrical smoke, or any other agent (such as dust) that would thicken the air to make it more apparent. More than just a film, Line Describing a Cone affirms cinema as a collective social experience.

Screening introduced by William Raban and Anthony McCall.

Programme repeated on Monday 6 May 2002, at 7:30pm

PROGRAMME NOTES

EXPANDED CINEMA

Friday 3 May 2002, at 7:30pm

London Tate Modern Level 7 East

CASTLE ONE

Malcolm Le Grice, 1966, b/w, sound, 20 min

“The light bulb was a Brechtian device to make the spectator aware of himself. I don’t like to think of an audience in the mass, but of the individual observer and his behaviour. What he goes through while he watches is what the film is about. I’m interested in the way the individual constructs variety from his perceptual intake.” —Malcolm Le Grice, Films and Filming, February 1971

“… totally Kafkaesque, but also filmically completely different from anyone else because of the rawness. The Americans are always talking about ‘rawness’, but it’s never raw. When the English talk about ‘raw’, they don’t just talk about it, it really is raw – it’s grey, it’s rainy, it’s grainy, you can hardly see what’s there. The material really is there at the same time as the image. With the Germans, it’s a high-class image of material, optically reproduced and glossy. The Americans are half-way there, but the English stuff looked like it really was home-made, artisanal, and yet amazingly structured. And I certainly thought Castle One was the most powerful film I’d seen, ever…” —Peter Gidal, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

“Malcolm said to me “Ideally in this film there should be a real light bulb hanging next to the screen, but that’s not possible.” And I said “It’s not possible to hang a light bulb?” He said “Well, I don’t see how we could possibly do this.” I said “Well the only question is how do we turn it on and off at the right moments? … Are you able to do that as a live performance?” He looked at me like the world was going to end! And I said “The switch will be there.”” —Jack Moore, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

TAKE MEASURE

William Raban, 1973, colour, silent, 2 min

“The thing that strikes me going into a cinema, because it is such a strange space and it’s organized to allow you to get enveloped by the whole illusion of film, when you try and think of it in terms of real dimensions it becomes very difficult. The idea of a sixty foot throw or a hundred foot throw from the projector to the screen just doesn’t enter into the equation. So I thought the idea of making a piece that made that distance between the projector and the screen more tangible was quite an interesting thing to do.” —William Raban, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

“Take Measure is usually the shortest of my films, measuring in feet that intangible space separating screen from projector box (which is counted on the screen by the image of a film synchronizer). Instead of being fed into the projector from a reel, the film is strung between projector and screen. When the film starts, the film snakes backwards through the audience as it is consumed by the projector.” —William Raban, Perspectives on British Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1977

DIAGONAL

William Raban, 1973, colour, sound, 6 min

“Diagonal is a film for three projectors, though the diagonally arranged projector beams need not be contained within a single flat screen area. This film works well in a conventional film theatre when the top left screen spills over the ceiling and the bottom right projects down over the audience. It is the same image on all three projectors, a double-exposed flickering rectangle of the projector gate sliding diagonally into and out of frame. Focus is on the projector shutter, hence the flicker. This film is ‘about’ the projector gate, the plane where the film frame is caught by the projected light beam.” —William Raban, Perspectives on British Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1977

“The first great excitement is finding the idea, making its acquaintance, and courting it through the elaborate ritual of film production. The second excitement is the moment of projection when the film becomes real and can be shared with the audience. The former enjoyment is unique and privileged; the second is not, and so long as the film exists, it is infinitely repeatable.” —William Raban, Arts Council Film-Makers on Tour catalogue, 1980

HAND GRENADE

Gill Eatherley, 1971, colour, sound, 8 min

“Although the word ‘expanded’ cinema has also been used for the open/gallery size/multi screen presentation of film, this ‘expansion’ (could still but) has not yet proved satisfactory – for my own work anyway. Whether you are dealing with a single postcard size screen or six ten-foot screens, the problems are basically the same – to try to establish a more positively dialectical relationship with the audience. I am concerned (like many others) with this balance between the audience and the film – and the noetic problems involved.” —Gill Eatherley, 2nd International Avant-Garde Film Festival programme notes, 1973

“Malcolm Le Grice helped me with Hand Grenade. First of all I did these stills, the chairs traced with light. And then I wanted it to all move, to be in motion, so we started to use 16mm. We shot only a hundred feet on black and white. It took ages, actually, because it’s frame by frame. We shot it in pitch dark, and then we took it to the Co-op and spent ages printing it all out on the printer there. This is how I first got involved with the Co-op.” —Gill Eatherley, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

LIGHT MUSIC

Lis Rhodes, 1975-77, b/w, sound, 20 min

“Lis Rhodes has conducted a thorough investigation into the relationship between the shapes and rhythms of lines and their tonality when printed as sound. Her work Light Music is in a series of ‘moveable sections’. The film does not have a rigid pattern of sequences, and the final length is variable, within one-hour duration. The imagery is restricted to lines of horizontal bars across the screen: there is variety in the spacing (frequency), their thickness (amplitude), and their colour and density (tone). One section was filmed from a video monitor that produced line patterns on the screen that varied according to sound signals generated by an oscillator; so initially it is the sound which produces the image. Taking this filmed material to the printing stage, the same lines that produced the picture are printed onto the optical soundtrack edge of the film: the picture thus produces the sound. Other material was shot from a rostrum camera filming black and white grids, and here again at the printing stage, the picture is printed onto the film soundtrack. Sometimes the picture ‘zooms’ in on the grid, so that you actually ‘hear’ the zoom, or more precisely, you hear an aural equivalent to the screen image. This equivalence cannot be perfect, because the soundtrack reproduces the frame lines that you don’t see, and the film passes at even speed over the projector sound scanner, but intermittently through the picture gate. Lis Rhodes avoids rigid scoring procedures for scripting her films. This work may be experienced (and was perhaps conceived) as having a musical form, but the process of composition depends on various chance operations, and upon the intervention of the filmmaker upon the film and film machinery. This is consistent with the presentation where the film does not crystallize into one finished form. This is a strong work, possessing infinite variety within a tightly controlled framework.” —William Raban, Perspectives on British Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1977

“The film is not complete as a totality; it could well be different and still achieve its purpose of exploring the possibilities of optical sound. It is as much about sound as it is about image; their relationship is necessarily dependent as the optical soundtrack ‘makes’ the music. It is the machinery itself which imposes this relationship. The image throughout is composed of straight lines. It need not have been.” —Lis Rhodes, A Perspective on English Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1978

LINE DESCRIBING A CONE

Anthony McCall, 1973, b/w, silent, 30 min

“Once I started really working with film and feeling I was making films, making works of media, it seemed to me a completely natural thing to come back and back and back, to come more away from a pro-filmic event and into the process of filmmaking itself. And at the time it all boiled down to some very simple questions. In my case, and perhaps in others, the question being something like “What would a film be if it was only a film?” Carolee Schneemann and I sailed on the SS Canberra from Southampton to New York in January 1973, and when we embarked, all I had was that question. When I disembarked I already had the plan for Line Describing a Cone fully-fledged in my notebook. You could say it was a mid-Atlantic film! It’s been the story of my life ever since, of course, where I’m located, where my interests are, that business of “Am I English or am I American?” So that was when I conceived Line Describing a Cone and then I made it in the months that followed.” —Anthony McCall, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

“One important strategy of expanded cinema radically alters the spatial discreteness of the audience vis-à-vis the screen and the projector by manipulating the projection facilities in a manner which elevates their role to that of the performance itself, subordinating or eliminating the role of the artist as performer. The films of Anthony McCall are the best illustration of this tendency. In Line Describing a Cone, the conventional primacy of the screen is completely abandoned in favour of the primacy of the projection event. According to McCall, a screen is not even mandatory: The audience is expected to move up and down, in and out of the beam – this film cannot be fully experienced by a stationary spectator. This means that the film demands a multi-perspectival viewing situation, as opposed to the single-image/single-perspective format of conventional films or the multi-image/single-perspective format of much expanded cinema. The shift of image as a function of shift of perspective is the operative principle of the film. External content is eliminated, and the entire film consists of the controlled line of light emanating from the projector; the act of appreciating the film – i.e., ‘the process of its realisation’ – is the content.” —Deke Dusinberre, “On Expanding Cinema”, Studio International, November/December 1975

Back to top

Date: 4 May 2002 | Season: Shoot Shoot Shoot 2002 | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT: SEMINAR

Saturday 4 May 2002, at 2pm

London Tate Modern

A symposium and gathering which will re-examine the period in which many British artists embarked on radical experiments with non-illusionist filmmaking and made important innovations in multi-screen and expanded cinema projection. Discussions will address the emergence of an underground movement, its international significance, and the relations between avant-garde film and mainstream cinema, experimental video, painting, sculpture, performance and photography.

Speakers include David Curtis from the AHRB Centre for British Film and Television Studies, film historians Ian Christie, Al Rees, and others. An artists’ panel featuring Peter Gidal, Anthony McCall, Lis Rhodes and Chris Welsby will be chaired by Michael Newman (Principal Lecturer in Research, Central Saint Martin’s School of Art). Plus selected special screenings. Many of the filmmakers whose work is featured in the season will be present and encouraged to contribute.

Presented by Tate Modern in collaboration with the School of Art at Central Saint Martins School of Art and Design.

This event will be webcast at www.tate.org.uk/modern/programmes/webcasting/

Date: 4 May 2002 | Season: Shoot Shoot Shoot 2002 | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

DOUBLE SCREEN FILMS

Saturday 4 May 2002, at 7:30pm

London Tate Modern

Widening the visual field increased the opportunity for both spectacle and contemplation. With two 16mm projectors side-by-side, time could be frozen or fractured in a more complex way by playing one image against another and creating a magical space between them. Each screening became a unique event, accentuating the temporality of the cinematic experience.

William Raban & Chris Welsby, River Yar, 1971-72, colour, sound, 35 min

Sally Potter, Play, 1971, b/w & colour, silent, 7 min

David Parsons, Mechanical Ballet, 1975, b/w, silent, 8 min

Chris Welsby, Wind Vane, 1972, colour, sound, 8 min

David Crosswaite, Choke, 1971, b/w & colour, sound, 5 min

Malcolm Le Grice, Castle Two, 1968, b/w, sound, 32 min

Raban & Welsby’s River Yar is a monumental study of landscape, nature, light and the passage of time. It employs real time and time-lapse photography to document and contrast the view of a tidal estuary over two three-week periods, in spring and autumn. The film stimulates cosmic awareness as each day is seen to have its elemental events. Sunrise brings in the light and sunset provides the ultimate fade-out. The use of different film stocks, and the depiction of twins seen in a twin-screen format, emphasises the fractured and slightly disorientating view from Sally Potter’s window in Play. David Parsons’ refilming of a stunt car demonstration pulses between frames, analytically transforming the motion into a visceral mid-air dance. Wind Vane (Chris Welsby) was shot simultaneously by two cameras whose view was directed by the wind. The gentle panning makes us subtly aware of the physical space (distance) between the adjacent frames. With a rock music soundtrack, Crosswaite’s Choke, suggests pop art in its treatment of Piccadilly Circus at night. Multiply exposed and treated images mirror each other or travel across the two screens. Castle Two by Malcolm Le Grice immediately throws the viewer into a state of discomfort as one tries to assess the situation, and then proceeds a long, obscure and perplexing indoctrination. “Is that coming through out there?”

Screening introduced by Malcolm Le Grice.

PROGRAMME NOTES

DOUBLE SCREEN FILMS

Saturday 4 May 2002, at 7:30pm

London Tate Modern

RIVER YAR

William Raban & Chris Welsby, 1971-72, colour, sound, 35 min

“The camera points south. The landscape is an isolated frame of space – a wide-angle view of a tidal estuary, recorded during Autumn and Spring. The camera holds a fixed viewpoint and marks time at the rate of one frame every minute (day and night) for three weeks. The two sequences Autumn and Spring, are presented symmetrically on adjacent screens. The first Spring sunrise is recorded in real time (24 fps) for 14 minutes, establishing a comparative scale of speed for the Autumn screen, where complete days are passing in one minute. Then both screens run together in stop-action until the Autumn screen breaks into a 14 minute period of real time for the final sunset into darkness. Recordings were made of landscape sound at specific intervals each day. Each screen has its own soundtrack which mixes with the other in the space of the cinema.” —William Raban & Chris Welsby, NFT English Independent Cinema programme notes, 1972

“Chris found the location.which was an ex-water mill in Yarmouth on the Isle of Wight, owned by the sons of the historian A.J.P. Taylor. We managed to get it for an astonishing rent of £5 a week. One of its upstairs windows happened to look over this river estuary, it was the kind of view we were looking for, so it was ideal in many ways. We’d worked out the conceptual model for the film, how we wanted it to look as a two-screen piece, more or less entirely in advance. We also knew what camera we wanted. There was really only the Bolex camera that would be suitable for filming it on. I made an electric motor for firing the time-lapse shots that was capable of giving time exposures as well as instantaneous exposures. Unknown to us of course, the first period of shooting coincided with the big coal miners’ strike, in the Ted Heath government, so the motor was redundant for most of the time; we had to shoot the film by hand. And it was quite interesting because we weren’t just making River Yar, we were down there for six weeks in the autumn and three weeks again the following spring, so we were also making other work. I was doing a series of tree prints in a wood nearby. And we invited people down to share the experience with us, so Malcolm, Annabel and Gill all came to stay.” —William Raban, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

PLAY

Sally Potter, 1971, b/w & colour, silent, 7 min

“In Play, Potter filmed six children – actually, three pairs of twins – as they play on a sidewalk, using two cameras mounted so that they recorded two contiguous spaces of the sidewalk. When Play is screened, two projectors present the two images side by side, recreating the original sidewalk space, but, of course, with the interruption of the right frame line of the left image and the left frame line of the right image – that is, so that the sidewalk space is divided into two filmic spaces. The cinematic division of the original space is emphasized by the fact that the left image was filmed in color, the right image in black and white. Indeed, the division is so obvious that when the children suddenly move from one space to the other, ‘through’ the frame lines, their originally continuous movement is transformed into cinematic magic.” —Scott MacDonald, A Critical Cinema 3, 1998

“To be frank, I always felt like a loner, an outsider. I never felt part of a community of filmmakers. I was often the only female, or one of few, which didn’t help. I didn’t have a buddy thing going, which most of the men did. They also had rather different concerns, more hard-edged structural concerns … I was probably more eclectic in my taste than many of the English structural filmmakers, who took an absolute prescriptive position on film. Most of them had gone to Oxford or Cambridge or some other university and were terribly theoretical. I left school at fifteen. I was more the hand-on artist and less the academic. The overriding memory of those early years is of making things on the kitchen table by myself…” —Sally Potter interviewed by Scott MacDonald, A Critical Cinema 3, 1998

MECHANICAL BALLET

David Parsons, 1975, b/w, silent, 8 min

“… I began to forge ideas that explored the making of the work and the procedure of events and ideas unfolding in space and time. Inevitably, this led to the consideration of the filmmaking apparatus as an integral element within the construction of the film. Taken literally of course, this applies to the making of any film, but I am referring to processes that do not attempt to hide the means of production and make the technique transparent, rather the very opposite. There are many parallels in other creative fields: the improvisational aspects of modern jazz, and Exercises in Style by the wonderful French writer Raymond Queneau. These examples spring to mind as background influences upon what I see now as an essentially modernist project, in that I was attempting to assert the material aspects of making, over what was depicted. So, to turn to the camera to attempt exhaust all the possibilities of its lenses, the film transportation mechanism, the shift of the turret, hand holding or tripods mounting, as conditioning factors within the films became the challenge. The project broadened out with seemingly endless possibilities offered by the film printer, the projector, and the screen.” —David Parsons, “Picture Planes”, Filmwaves No. 2, November 1997

“Several areas of interest intersect in the making of Mechanical Ballet: an interest in ‘found’ footage (relating to collage, assemblage), the manipulation of the film strip and the film frame, time and duration, projection and the screen, and the film printing process, to highlight some of the main concerns. In the early ’70s I began a series of experiments with ways of refilming and improvising new constructions with different combinations of frames. Thus new forms emerged from the found material that I had selected to use as my base material. In one work I extended the closing moments of the tail footage of a film, consisting of less than a second of flared out frames, stretching it into two minutes forty five seconds, 100 foot of film. In another I used some early documentation of time and motion studies of factory workers performing repetitive tasks on machinery. A speedometer mounted in the corner of the frame monitored the progress of their actions in relation to the time it took to perform their tasks. I found the content both disturbing and absurd and sought to exemplify this by exaggerating the action and ‘stalling’ the monitoring process by racking the film back and forth through the gate. The original material that formed the basis for Mechanical Ballet was an anonymous short reel of film of what appeared to be car crash tests. In the original these tests are carried out in a deadpan and somewhat cumbersome manner. Reworked into a two-screen film and divorced from their original context they take on both a sinister and humorous quality. Using similar techniques to the aforementioned films, the repetitive refilming of the original footage in short sections emphasised the process of film projection. Somewhat like a child’s game of two steps forward and one back, the viewer is made aware of the staggered progress of the film through the gate. In sharp contrast to the almost stroboscopic flicker of the rapid movement of the frames that alternate in small increments of light and dark exposures, the image takes on new meanings; the distorted reality of two heavy objects (the cars, one on each of the screens) ‘dancing’ lightly in space.” —David Parsons, 2002

WIND VANE

Chris Welsby, 1972, colour, sound, 8 min

“At that time, the automatic gyros on sailboats were run from a wind vane that was attached through a series of mechanical devices to the rudder. The wind vane actually set itself to the wind and you adjusted all the gear and that then steered the boat in the particular orientation to the wind. On various sailing trips, I’d been looking at this thing thinking, “Hmm, that’s really interesting … I wonder if I could set a camera on something like that?” Because, for me the idea of a sailboat travelling from A to B was an interesting sort of metaphor for the way that people interacted with nature. In sailing, as you may know if you’ve done it, you can’t just go from A to B, you have to adjust everything to which way the tide is going, which way the wind’s going and so on and so forth. Hopefully, eventually, you would get to B but, really, in between time there would have been all sorts of other events that would affect that: speed of tides, speed of wind, no wind, etc. So that seemed to me to be an interesting metaphor, so then I started building wind vanes and attaching cameras to them…” —Chris Welsby, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

“The spatial exigencies of twin-screen projection become of primary importance in this film because the adjacency of the screen images is related to the adjacency of the filming technique: two cameras were placed about 50 feet apart on tripods which included wind vane attachments, so that the wind direction and speed determined the direction and speed of the pans of the two freely panning cameras. The landscape images are more or less coincident, and the attempt by the spectator to visually conjoin the two spaces (already conjoined on the screen) sets up the primary tension of this film. As the cameras pan, one expects an overlap between the screens (from one to another) but gets only overlap in the screens (when they point to the same object). The adjacency of the two spaces is constantly shifting from (almost) complete similarity of field to complete dissimilarity. And within the dissimilarity of space can be more or less contiguous. The shrewd choice of a representational image which exploits the twin-screen format is Welsby’s strength.” —Deke Dusinberre, “On Expanding Cinema”, Studio International, November/December 1975

CHOKE

David Crosswaite, 1971, b/w & colour, sound, 5 min

“Choke was made from 8mm footage that I had blown up to 16mm. It was colour film I took of the Coca-Cola sign in Piccadilly Circus, which is now vastly different. I think that it was the fact that this expanded film thing was happening, and Malcolm would’ve said, “Well, aren’t you going to make any double screen films, then?” and I said “Can do, yeah”! I just had this idea of using this image that I had, and again started painstakingly sello-taping little cuttings onto film so it tracked across the screen in certain parts. I must have been an absolute glutton for punishment at the time.” —David Crosswaite, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

“… But nevertheless you get characters like Crosswaite, whose films I find absolutely magical, I think they’re the most seminal works of the whole Co-op period. He certainly didn’t engage in the arguments that were going on, he stood aloof from it. In fact he would the erode attempts of that hierarchical thing, his presence eroded it. He never really engaged in the theoretical arguments, the polemics, at all, but nevertheless he produced the most seminal, the most beautiful work probably of the period. He certainly wasn’t excluded, and he was always there to deflate this idea of exclusivity. He refuses to engage. He would just say, “Here’s my film” … and yet they are beautifully polemical, they’re just extraordinary pieces or work.” —Roger Hammond, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

CASTLE TWO

Malcolm Le Grice, 1968, b/w, sound, 32 min

“This film continues the theme of the military/industrial complex and its psychological impact upon the individual that I began with Castle One. Like Castle One, much use is made of newsreel montage, although with entirely different material. The film is more evidently thematic, but still relies on formal devices – building up to a fast barrage of images (the two screens further split – to give 4 separate images at once for one sequence). The images repeat themselves in different sequential relationships and certain key images emerge both in the soundtrack and the visual. The alienation of the viewer’s involvement does not occur as often in this film as in Castle One, but the concern with the viewer’s experience of his present location still determines the structure of certain passages in the film.” —Malcolm Le Grice, London Film-Makers’ Co-operative catalogue, 1968

“Le Grice’s work induces the observer to participate by making him reflect critically not only on the formal properties of film but also on the complex ways in which he perceives that film within the limitations of the environment of its projection and the limitations created by his own past experience. A useful formulation of how this sort of feedback occurs is contained in the notion of ‘perceptual thresholds’. Briefly, a perceptual threshold is demarcation point between what is consciously and what is pre-consciously perceived. The threshold at which one is able to become conscious of external stimuli is a variable that depends on the speed with which the information is being projected, the emotional charge it contains and the general context within which that information is presented. This explains Le Grice’s continuing use of devices such as subliminal flicker and the looped repetition of sequences in a staggered series of changing relationships.” —John Du Cane, Time Out, 1977

Back to top

Date: 5 May 2002 | Season: Shoot Shoot Shoot 2002 | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

LONDON UNDERGROUND

Sunday 5 May 2002, at 3:00pm

London Tate Modern

As equipment became available for little cost, avant-garde film flourished in mid-60s counter-culture. Early screenings at Better Books and the Arts Lab provided a vital focus for a new movement that infused Swinging London with a fresh subversive edge.

Antony Balch, Towers Open Fire, 1963, b/w, sound, 16 min

Jonathan Langran, Gloucester Road Groove, 1968, b/w, silent, 2 min

Jeff Keen, Marvo Movie, 1967, colour, sound, 5 min

John Latham, Speak, 1962, colour, sound, 11 min

Stephen Dwoskin, Dirty, 1965-67, b/w, sound, 10 min

Stuart Pound, Clocktime Trailer, 1972, colour, sound, 7 min

Simon Hartog, Soul In A White Room, 1968, colour, sound, 3.5 min

Peter Gidal, Hall, 1968-69, b/w, sound, 10 min

Malcolm Le Grice, Reign Of The Vampire, 1970, b/w, sound, 11 min

Made independently on 35mm, in collaboration with William Burroughs, Towers Open Fire is rarely considered in histories of avant-garde film, despite its experiments in form and representation. It combines strobe cutting, flicker, degraded imagery and hand-painted film to create a visual equivalent to the author’s narration. Gloucester Road Groove, featuring Simon Hartog and David Larcher, is a spirited celebration of youthful exuberance, the excitement of shooting with a movie camera. Jeff Keen’s vision is a uniquely British post-war accumulation of art history, comic books, old Hollywood and new collage. Positioned between happenings and music hall, he performs dada actions in the “theatre of the brain”. Marvo Movie is just one of countless works that mix live action with animation, but is notable for its concrete sound by Co-op co-founder Bob Cobbing. Speak, with hypnotic flashing discs and relentless noise track, anticipated many of the anti-illusionist arguments that the Co-op later embodied. The film was made in 1962, but its advanced radical nature made it largely unknown until later screenings at Better Books brought Latham into contact with like-minded contemporaries. In Dirty, Dwoskin accentuates the dirt and scratches on the film’s surface while interrogating the erotic imagery through refilming. The systematic cutting of Stuart Pound’s film, and its cyclical soundtrack, derives from a mathematical process that condenses a feature length work (Clocktime I-IV) into a short ‘trailer’. Soul in a White Room is a subtle piece of social commentary by Simon Hartog, an early Co-op activist with a strong political conscience. Peter Gidal questions illusory depth and representation through focal length, editing and (seeming) repetition in Hall. Reign of the Vampire, from Le Grice’s paranoiac How to Screw the C.I.A., or How to Screw the C.I.A.? series, takes the hard line in subversion. Familiar “threatening” signifiers, pornography and footage from his other films is overlaid with travelling mattes, united with a loop soundtrack, to form a relentless assault.

Screening introduced by Stephen Dwoskin.

PROGRAMME NOTES

LONDON UNDERGROUND

Sunday 5 May 2002, at 3:00pm

London Tate Modern

TOWERS OPEN FIRE

Antony Balch, 1963, b/w, sound, 16 min

“Towers Open Fire is a straight-forward attempt to find a cinematic equivalent for William Burroughs’ writing: a collage of all the key themes and situations in the books, accompanied by a Burroughs soundtrack narration. Society crumbles as the Stock Exchange crashes, members of the Board are raygun-zapped in their own boardroom, and a commando in the orgasm attack leaps through a window and decimates a family photo collection… Meanwhile, the liberated individual acts: Balch himself masturbates (“silver arrow through the night…”), Burroughs as the junkie (his long-standing metaphor for the capitalist supply-and-demand situation) breaks on through to the hallucinatory world of Brion Gysin Dream Machines. Balch lets us stare into the Dream Machines, finding faces to match our own. “Anything that can be done chemically can be done by other means.” So the film is implicitly a challenge to its audience. But we’re playing with indefinables that we don’t really understand yet, and so Mikey Portman’s music-hall finale is interrupted by science-fiction attack from the skies, as lost boardroom reports drift through the countryside…” —Tony Rayns, “Interview with Antony Balch”, Cinema Rising No.1, April 1972

“Installations shattered – Personnel decimated – Board Books destroyed – Electronic waves of resistance sweeping through mind screens of the earth – The message of Total Resistance on short wave of the world – This is war to extermination – Shift linguals – Cut word lines – Vibrate tourists – Free doorways – Photo falling – Word falling – Break through in grey room – Calling Partisans of all nations – Towers, open fire” —William Burroughs, Nova Express, 1964

GLOUCESTER ROAD GROOVE

Jonathan Langran, 1968, b/w, silent, 2 min

“A film for children and savages, easily understood, non didactic fantasies. Urban landscapes…Strolling single frames.” —Jonathan Langran, London Film-Makers’ Co-operative distribution catalogue, 1977

“I felt really high with all these people around. I was kind of a provincial film student and the youngest of everyone and there were fashion photographers, David Larcher who was very glamorous, there was Simon Hartog who was kind of intellectual … all sorts of people, wonderful women that would come around, friends, and I was always in awe of them and we used to go out to restaurants and that was all a very big thing for me. So one evening we went to Dino’s in Gloucester Road and I took the camera. I think I’d been using it all day, I just liked cameras and I filmed us going to eat, and we came back again, and I still kept filming! Gloucester Road was kind of cosmopolitan, late at night… it was exotic, very exotic, it wasn’t your dour kind of thing shot at 5 o’clock or 6 o’clock, Gloucester Road was buzzing.” —Jonathan Langran, interview with Mark Webber, 2002

MARVO MOVIE

Jeff Keen, 1967, colour, sound, 5 min

“Movie wizard initiates shatterbrain experiment – Eeeow! – the fastest movie film alive – at 24 or 16fps even the mind trembles – splice up sequence 2 – flix unlimited, and inside yr very head the images explode – last years models new houses & such terrific death scenes while the time and space operator attacks the brain via the optic nerve – will the operation succeed – will the white saint reach in time the staircase now alive with blood – only time will tell says the movie master – meanwhile deep inside the space museum…” —Ray Durgnat, London Film-Makers’ Co-operative distribution catalogue, 1968

“I was never part of the early 70s scene among the independent filmmakers – very much anti-American, anti-Hollywood. ‘Industrial Cinema’ they used to call it, which is true, but I never felt that antipathy towards commercial cinema. It was awful being a fucking misfit, I can tell you. I’d done my footsoldiering for the communist party and everything in those days – factory gates and all that shit, “ban the bomb”… So by the time of 1970, I’d got out of that. As for sexual liberation, I’d been happily married! And the drug scene didn’t mean anything to me because I’m puritanical. I’m a misfit.” —Jeff Keen, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

SPEAK

John Latham, 1962, colour, sound, 11 min

“Latham’s second attack on the cinema. Not since Len Lye’s films in the thirties has England produced such a brilliant example of animated abstraction. Speak is animated in time rather than space. It is an exploration in the possibilities of a circle which speaks in colour with blinding volume. Speak burns its way directly into the brain. It is one of the few films about which it can truly be said, “it will live in your mind.”” —Ray Durgnat, London Film-Makers’ Co-operative distribution catalogue, 1968

“In 1966 Pink Floyd were playing their free-form, experimental rock at the Talbot Road Tabernacle (a church hall), Powis Square, Notting Hill Gate. On several occasions, Latham projected his film Speak as the group played. Since the film had a powerful flicker effect, the result was equivalent to strobe lighting. Film and music ran in parallel – there was no planned synchronization. Thinking to combine movie and music more systematically, Latham asked Pink Floyd to supply a soundtrack. The band agreed and a recording session took place. The artist explained that he wanted music that would take account of the strong, rhythmical pulse of the film. This the acid rock group proved unable or unwilling to provide; consequently, the association was terminated. A soundtrack was eventually added to one print of Speak: Latham placed a contact mike on the floor to pick up the beat of a motor (rhythm) driving a circular saw (musical note) while it was being used to saw up books (percussion and bending note). The film reaches a tremendous climax as the increasingly harsh whine of the electric saw combines with the frenetic sequence of images and flashes of light.” —John A. Walker, John Latham – The Incidental Person – His Art and Ideas, 1995

DIRTY

Stephen Dwoskin, 1965-67, b/w, sound, 10 min

“Dirty is remarkable for its sensuousness, created partly by the use of rephotography which enables the filmmaker a second stage of response to the two girls he was filming, partly by the caressing style of camera movement and partly by the gradual increase of dirt on the film itself, increasing the tactile connotations generated by rephotography. The spontaneity of Dwoskin’s response to the girls’ sensual play is matched by the spontaneity of his response to the film of their play. The rhythms of the girls’ movements are blended with the rhythms of the primary and secondary stage camera movements and these rhythms relate to the steady pulse emanating from the center of the image as a result of the different projector and camera speeds during rephotography. The soundtrack successfully prevents the awareness of audience noise (the inevitable distraction of silent cinema) by filling the aural space, but not drawing attention to itself. You tend not to notice it after a while and can therefore concentrate on what is most importantly a visual-feel film.” —John Du Cane, Time Out, 1971

“The refilming enabled the actions of the two girls to be emphasized to convey the tension and beauty of such a simple and emphatic gesture as a hand reaching out: frozen, and then moving slowly, then freezing, then moving again, and all the while creating tension and space before the contact. The refilming was done on a small projector and this enabled me to capture the pulsing (cycles) of the projector light, which gave off a throbbing rhythm throughout, and increased the mood of sensuality.” —Stephen Dwoskin, Film Is…, 1975

CLOCKTIME TRAILER

Stuart Pound, 1972, colour, sound, 7 min

“A time truncation film trailer for the rather long film called Clocktime. Film made as a totally systematic stream of hitherto unrelated events welded together into a colour interchange frame i.e. image (1), image (2), image (3)… repeat time cycle. 6 frames, 1/4 second, then images move further along their original time base; a very linear film.” —London Film-Makers’ Co-operative distribution catalogue, 1977

“I wasn’t particularly interested in making films about poetry but films that had got quite a strong sexual charge. For instance, in Clocktime Trailer there’s a woman in it who used to work for the Other Cinema years ago – Julia Meadows. I was absolutely fascinated with her, it was almost like having sex through the lens of the camera. I have now seen Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom, but I’d not seen that at the time. It came out about 1960, here was such a hoo-hah about it and I was only about 16. Subsequently when I saw it I was: “Oh my god”. I could see how I was a real menace!” —Stuart Pound, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

SOUL IN A WHITE ROOM

Simon Hartog, 1968, colour, sound, 3.5 min

“Films are not bombs. No cultural object, as such, can have such a direct and measurable effect on the physical universe. Film works in the more ambiguous sphere of art and ideas. It cannot change the world, but it can change those who can change it. Film makes use of values that exist within a culture, and a society’s culture is more pervasive than its politics. The alteration, or even the questioning of existing value is the alteration of society. The established cultural hierarchy maintains itself by protecting and enforcing the ideas that keep it in power. Anything that attacks, questions, or provides new values is a threat. The culture allows only that which will not challenge its assumptions; everything else must be forced underground. Film, as a cultural and social activity, contains within itself a potential for change. Besides the great reporting and recording qualities of film, which provide it with a direct reference to the culture, it also provides the sense of magic. It possesses this sense in its ability to capture life; to capture movement and to fracture time and space. The main characteristics of magic are its indirect reference to the culture, and to the past and its derivation from very specific emotional experiences. Magic’s base is those emotional experiences where the truth of the experience is not revealed by reasoning, but by the interplay of these emotions on the individual human…” —Simon Hartog & Stephen Dwoskin, “New Cinema”, Counter Culture: The Creation of an Alternative Society, 1969

“Soul in a White Room was filmed by Simon Hartog around autumn 1968. Music on the soundtrack is “Cousin Jane” by The Troggs. The man is Omar Diop-Blondin, the woman I don’t recall her name. Omar was a student active in 1968 during “les evenement de Mai et de Juin” at the Faculte de Nanterre, Universite de Paris. Around this time, Godard was in London shooting Sympathy for the Devil / One Plus One with the Stones and Omar was here for that too, appearing with Frankie Y (Frankie Dymon) and the other Black Panthers in London … maybe Michael X too. After returning to Senegal, Omar was imprisoned and killed in custody in ’71 or ’72. I believe his fate is well known to the Senegalese people.” —Jonathan Langran, interview with Mark Webber, 2002

HALL

Peter Gidal, 1968-69, b/w, sound, 10 min

“Hall manages, in its ten minutes, to put our perception to a rather strenuous test. Gidal will hold a static shot for quite a long time, and then make very quick cuts to objects seen at closer range. There is just a hallway and a room partially visible beyond, pictures (one of Godard) on a wall, fruit on a table, and so forth. The commonplace is rendered almost monotonous as we become increasingly familiar with it from a fixed and sustained viewpoint, and then we are disoriented by the closer cuts and also by the sudden prolonged ringing of an alarm. But even at the point of abrupt disorientation we remain conscious of the manipulation applied.” —Gordon Gow, “Focus on 16mm”, Films and Filming, August 1971

“Demystified reaction by the viewer to a demystified situation; a cut in space and an interruption of duration through (obvious) jumpcut editing within a strictly defined space. Manipulation of response and awareness thereof: through repetition and duration of image. Film situation as structured, as recorrective mechanism. (Notes from 1969) Still utilizing at that time potent (signifying, overloaded) representations. (1972)” —Peter Gidal, London Film-makers’ Co-operative distribution catalogue, 1974

“In Hall, extremely stable, normally reproduced objects are given clear from the beginning, the editing, moreover, reducing the distance from which they are seen, cutting in to show and to detail them, repetition then undercutting their simple identification; the second time around, a bowl of fruit cannot be seen as a bowl of fruit, but must be seen as an image in a film process, detached from any unproblematic illusion of presence, as a production in the film, a mark of the presence of that.” —Stephen Heath, “Repetition Time”, Wide Angle, 1978

REIGN OF THE VAMPIRE

Malcolm Le Grice, 1970, b/w, sound, 11 min

“It was about trying to get a mental position which defied the way in which the then-C.I.A. was kind of intervening in the world. But it was more, not a joke, but an icon title. I suppose it said to me and to other people, “Make your barb against the C.I.A.” A lot of my early work, all that aggressive work, has a political paranoia about it: the idea that there are hidden forces of the military-industrial establishment, which are manipulating us from within that power. Obviously, they were – people were having their telephones tapped though I don’t suppose for one minute that my telephone was interesting enough to tap. Reign of the Vampire is that kind of paranoid film. It’s a hovercraft that comes in, but it could easily be a tank with the army getting out of it … The idea of a military force that can sneak in somewhere, and the computer images. Threshold is in similar territory, about the borders and so on but very abstract. It’s about that hidden sense of force.” —Malcolm Le Grice, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

“The film is made from six loops in pairs (simple superimposition, but made by printing through both loops together rather than in two runs following each other, the effect of this is largely to eliminate the transparent aspect of superimposition). In content, the film comes near to being a synthesis of the How to Screw the C.I.A. or How to Screw the C.I.A.? series; it draws on pieces of film from the other films, and combines these with the most ‘disturbing’ of the images which I have collected. It also relates to the ‘dream’/fluid association sequence in Castle Two; it is a kind of on-going under-consciousness which repeats and does not resolve into any semantic consequence. One of the factors of the use of the loop, which interests me particularly, is the way in which the viewer’s awareness undergoes a gradual transformation from the semantic/associative to the abstract/formal, even though the ‘information’ undergoes only limited change. The sound has a similar kind of loop/repetition structure.” —Malcolm Le Grice, How to Screw the C.I.A. or How to Screw the C.I.A.? programme notes, 1970

Back to top

Date: 12 May 2002 | Season: Shoot Shoot Shoot 2002 | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

STRUCTURAL / MATERIALIST

Sunday 12 May 2002, at 3:00pm

London Tate Modern

The enquiry into the material of film as film itself was an essential characteristic of the Co-op’s output. These non- and anti- narrative concerns were fundamentally argued by the group’s principal practising theorists Malcolm Le Grice and Peter Gidal.

Roger Hammond, Window Box, 1971, b/w, silent, 3 min (18fps)

Mike Leggett, Shepherd’s Bush, 1971, b/w, sound, 15 min

David Crosswaite, Film No. 1, 1971, colour, sound, 10 min

Mike Dunford, Tautology, 1973, b/w, silent, 5 min

Peter Gidal, Key, 1968, colour, sound, 10 min

John Du Cane, Zoom Lapse, 1975, colour, silent, 15 min

Malcolm Le Grice, Little Dog For Roger, 1967, b/w, sound, 13 min

Gill Eatherley, Deck, 1971, colour, sound, 13 min

In explaining their (quite different) ideas in some erudite but necessarily dense texts Le Grice and Gidal have in some ways contributed to misunderstandings of this significant tendency in the British avant-garde. (For example, It is not the case, as is often proposed, that films were made to justify their theories.) Le Grice was instrumental in acquiring, installing and operating the equipment at the Co-op workshop that afforded filmmakers the hands-on opportunity to investigate the film medium. His own work developed through direct processing, printing and projection, providing an understanding of the material with which he could examine filmic time through duration, while touching on spectacle and narrative. By contrast, Gidal’s cool, oppositional stance was refined to refute narrative and representation, denying illusion and manipulation though visual codes. His uncompromising position resists all expectations of cinema, even modernist formalism and abstraction. The artistic and theoretical relationship of these two poles of the British avant-garde, who were united in opposing ‘dominant cinema’, is a complex set of divergences and intersections.

Originally intended as a test strip, the first film produced at the Dairy on the Co-op step-printer was Mike Leggett’s Shepherd’s Bush, in which an obscure loop of abstract footage relentlessly advances from dark to light. The two short films by Roger Hammond and Mike Dunford concisely encapsulate an idea; while Window Box exploits the viewer’s anticipation of camera movement and shrewdly transforms a seemingly conventional viewpoint, the permanence of the cinematic frame is the focus of Tautology’s brief enquiry. By translating footage across different gauges, Crosswaite and Le Grice explore variations in film formats: Film No. 1 uses permutations and combinations of unsplit 8mm, while Little Dog for Roger directly prints 9.5mm home movies onto 16mm stock. In Key, Gidal plays on the ambiguity of an image to challenge and refute the observer’s interpretation of it, while intensifying disorientation through his manipulation of the soundtrack. Du Cane’s Zoom Lapse comprises dense multiple overlays of imagery, vibrating the moment, while Eatherley’s Deck re-photographs a reel of 8mm film, which undergoes a mysterious transformation through refilming, colour changing and printing.

Screening introduced by Roger Hammond.

PROGRAMME NOTES

STRUCTURAL / MATERIALIST

Sunday 12 May 2002, at 3:00pm

London Tate Modern

WINDOW BOX

Roger Hammond, 1971, b/w, silent, 3 min (18fps)

“In the small masterpiece Window Box, Hammond sets up a situation which is mystified in its presentation, and yet at the same time demands of (and allows) the viewer to demystify the given visual impulses. The situation presented includes thus within its own premises the objective factors which determine the possibility and probability of successful analysis. The criteria one uses to evaluate, interpret, are secondary to this conceptually-determined process of working out what is. We are taken into a post-logical empiricism which realizes the sensual strength of illusion which at the same time using precisely that to refer to precision of information. The opposite of Cartesian in its in-built negation of any aspect outside of the given system. Hammond is non-atomistic, non-referential within a specific, set-up, and defined closed system. Thus, a pure attitude. Hammond is purifying the conceptual and non-psychological aspect of his work to the point where it increasingly represents his calculable mental system: the nonreferential structural obligation. He does not create a whole system, however; rather, he deciphers one.” —Peter Gidal, “Directory of UK Independent Film-Makers”, Cinema Rising No. 1, April 1972

“Roger Hammond’s movies are short studies of apparently simple subjects…they induce a tight awareness of how these relations can be radically transformed by subtle shifts in film process; shifts of light value, angle, movement, framing, etc… The illusions of cinema as they bend our consciousness, become the focus of our attention. In Window Box, a simple subject takes on multiple dimensions in a ghostly world created by the process of rephotographing projected negative footage. There is a gentle reminder in this process in the framing of the eventual image, which incorporates in its composition a horizontal bar of light from the wall from which the film is being rephotographed.” —John Du Cane, Time Out, 1971

SHEPHERD’S BUSH

Mike Leggett, 1971, b/w, sound, 15 min

“Shepherd’s Bush was a revelation. It was both true film notion and demonstrated an ingenious association with the film-process. It is the procedure and conclusion of a piece of film logic using a brilliantly simple device; the manipulation of the light source in the Film Co-op printer such that a series of transformations are effected on a loop of film material. From the start Mike Leggett adopts a relational perspective according to which it is neither the elements or the emergent whole but the relations between the elements (transformations) that become primary through the use of logical procedure. All of Mike Leggett’s films call for special effort from the audience, and a passive audience expecting to be manipulated will indeed find them difficult for they seek a unique correspondence; one that calls for real attention, interaction, and anticipation/correction, a change for the audience from being a voyeur to being that of a participant.” —Roger Hammond, London Film-Makers Co-operative distribution catalogue supplement, 1972

“The process of film-making should emphasise the imaginative, and the contact between film-maker and spectator should become more direct. Shepherd’s Bush was made through a process contrary to the generally accepted method of making a film. It was without a script, without a camera, without the complicated route through task delegation. The entity of the film was conceived through the reappraisal of a Debrie Matipo step-contact printer. Designed such that with precise control of the light reaching the print stock after having passed through filters, aperture band and the negative, it was possible to demonstrate the gradual way in which the projection screen could turn from black to white. First, a suitable image on an existing piece of positive stock was found with which to produce a master negative. The shot was only ten seconds in length but contained a range of tones from one end of the grey scale to the other. It was loaded into the printer as a loop, and subsequently a print which repeated the action was made from the negative. Only part of the viewer’s attention should be taken with the perception of the figurative image on the screen. It should however, be dynamic enough to warrant careful inspection should the viewer’s attention turn to it. A thirty-minute version was made first, but on viewing was judged too long, so for the next version half this length was judged correct. A soundtrack was made matching in audio terms the perceptible changes in visual quality not usually encountered within the environment of the cinema. This film realized total control over the making of a film, from selection of the original camera stock, through exposure, processing, printing, processing, projection, cataloguing, and distribution.” —Mike Leggett, excerpts from unpublished notes, 1972

FILM NO. 1

David Crosswaite, 1971, colour, sound, 10 min

“Film No. 1 is a ten minute loop film. The systems of superimposed loops are mathematically interrelated in a complex manner. The starting and cut-off points for each loop are not clearly exposed, but through repetitions of sequences in different colours, in different material realities (i.e. negative, positive, bas-relief, neg/pos overlay) yet in a constant rhythm (both visually and on the soundtrack hum), one is manipulated to attempt to work out the system-structure. One relates to the repetitions in such a way that one concentrates on working out the serial formula while visually experiencing (and enjoying) the film at the same time. One of the superimposed loops is made of alternating mattes, so that the screen is broken up into four more or less equal rectangles of which, at any one moment, two or three are blocked out (matted). The matte-positioning is rhythmically structured, thus allowing each of the two represented images to flickeringly appear in only one frame-corner at a time. This rhythm powerfully strengthens the film’s existence as selective reality manipulated by the filmmaker and exposed as such. The mattes are slightly ‘off’; there is no perfect mechanical fit, so that the process of the physical matte-construction by the filmmaker is constantly noticeable, as one matte (at times of different hue or different colour) blends over the edge of the matte next to it (horizontally or vertically). The film deals with permutations of material, in a prescribed manner, but one by no means necessary or logical (except within the film’s own constructed system/serial). The process of looping a given image is already using film for its structural and abstract power rather than for a conventional narrative or ‘content’. But it is the superimposition of the black mattes which gives the film its extremely rich texture, and which separates it from so many other, less complex, loop-type films. Crosswaite works, in this film, with two basic images: Piccadilly at night and a shape which suggests at moments a 3-D close-up of a flowerlike organic growth or a Matisse-like abstract 2-D cutout. Depending on the colour dye of the particular film-segment and the positive/negative interchange, the object changes shading and constanyly re-forms from one dimension to the other, while shifting our perceptions from its reality as 3-dimensional re-presentation to its reality as cutout filling the film-frame with jagged edged blackness.” —Peter Gidal, NFT English Independent Cinema programme notes, 1972

TAUTOLOGY

Mike Dunford, 1973, b/w, silent, 5 min

“Regarding the in-built tautological aspects of perceptual structuring. Since refuted.” —Mike Dunford, London Film-Makers’ Co-operative distribution catalogue, 1977

“Each time I make a film I see it as a kind of hypothesis, or a questioning statement, rather than a flat assertion of any particular form or idea… Each film is a film experiment in the sense that the most attractive features are those that work… My films are not about ideas, or aesthetics, or systems, or mathematics, but are about film, film-making, and film-viewing, and the interaction and intervention of intentive self-conscious reasoning activity in that context.” —Mike Dunford, 2nd International Avant-Garde Festival programme notes, 1973

“Its pretty obvious isn’t it? That’s the kind of film that me and Roger Hammond talked about. It’s because we actually spent quite a bit of time hanging out in the Co-op, processing things and talking about ideas. He’d read Derrida and all that kind of stuff, and as a result I read some of it too. And that’s how I would have got to make something like Tautology, by talking to someone like him A very simple idea, simply done; it does one thing and that’s all it does.” —Mike Dunford, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

KEY

Peter Gidal, 1968, colour, sound, 10 min

“… an enclosed and progressive disembowelment of durational progression. He draws out singularities … he allows the camera only a fenced in area, piecemeal. He lets the gaze hold on objects and constantly repeats … this permits the possibilities of the discrepancies between one’s own seeing and seeing with the camera to become distinct, and this in turn allows for a completely different experience of the surroundings.” —Birgit Hein, Film Im Underground, 1971

“Structural/Materialist film attempts to be non-illusionist. The process of the film’s making deals with devices that result in demystification or attempted demystification of the film process. But by ‘deals with’ I do not mean ‘represents’. In other words, such films do not document various film procedures, which would place them in the same category as films which transparently document a narrative, a set of actions, etc. Documentation, through usage of the film medium as transparent, invisible, is exactly the same when the object being documented is some ‘real event’, some ‘film procedure’, some ‘story’, etc. An avant-garde film defined by its development towards increased materialism and materialist function does not represent, or document, anything. The film produces certain relations between segments, between what the camera is aimed at and the way that ‘image’ is presented. The dialectic of the film is established in that space of tension between materialist flatness, grain, light, movement, and the supposed reality that is represented. Consequently, a continual attempt to destroy the illusion is necessary. In Structural/Materialist film, the in/film (not in/frame) and film/viewer material relations, and the relations of the film’s structure, are primary to any representational content. The structuring aspects and the attempt to decipher the structure and anticipate/recorrect it, to clarify and analyze the production-process of the specific image at any specific moment, are the root concern of Structural/Materialist film. The specific construct of each specific film is not the relevant point; one must beware not to let the construct, the shape, take the place of the ‘story’ in narrative film. Then one would merely be substituting one hierarchy for another within the same system, a formalism for what is traditionally called content. This is an absolutely crucial point.” —Peter Gidal, “Theory and Definition of Structural/Materialist Film”, Structural Film Anthology, 1976

ZOOM LAPSE

John Du Cane, 1975, colour, silent, 15 min

“If I had to compare my work with another activity, I would first point to two related musics: Reggae and certain West African music. If I had to label my work, I would choose a term radically opposed to ‘Structural’. I would say that I made ‘Ecstatic Cinema’ … I would like to think that the ecstatic is our birthright and to remember that ecstasy has many dimensions: we know that, from the Greek, we are talking about ‘a standing outside’ of oneself. This is meditation. And in the process of meditation, both rapture and a deep peace can co-exist. If my films work as intended, they will help you into ecstasy, and they will do this by satisfying in a polymorphic manner. The films are very physical, they are polyrhythmic and they are patterned in a manner designed to create a very definite way of seeing, of experiencing. I intend my films to jump out at you from their dark spaces, their gaps, their elisions, to vibrate in your whole being in the very manner and rhythm of felt experience. The magic of film for me is the possibility to portray these complex interlacings unfolding through time. You can watch one of my films, and see two films simultaneously; one of my mind and one of yours. I say film of ‘my mind’, but what I want to emphasise, because the films emphasise it, is that is a film of my being. The last thing I want my films to be is a purely mental event. This would be to deny a large part of the spectrum of the film.” —John Du Cane, “Statement on Watching My Films: A Letter from John Du Cane”, Undercut 13, 1984-85

“I was interested in film as a sculptural medium, and as a way to have the viewer be more aware of his viewing process, of his consciousness. My films were meditative at a time when that phrase wasn’t a popular term to use, but most of the films were designed to reflect the viewer back on themself. I also usually wanted my films to be very physical experiences, I wanted to make the experience work on really all of the main levels of energy; the physical, the intellectual and the aspects of awareness that we associate with consciousness. In Zoom Lapse I was also interested in working with the way we perceive time and space as it can be manipulated through the camera. Of course part of the content of this film had to do with the camera’s ability to squeeze our perspective through the process of zooming in and zooming out on a particular area. In the making of the film I actually lapsed the zoom process, so that I would shoot a single frame that had a zoom within it, and sequences in the film that were more extended zooms, so I took a very simple shot. I was living on a canal in Hamburg in a kind of romantic, old warehouse district, about all that was left after the bombing of the city. There was an old set of warehouse windows across the way and so I was interested in exploring the ways that you could squeeze space and watch the relationships between your time perception and your perception of space and how the two interact. There’s a process in the film, that happens in many of my other films, where I want the viewer to be pretty conscious that what they’re seeing is not something that exists on the celluloid, that there’s a way they’re manufacturing in the viewing process. The film should very obviously be something that if you come back and watch it a second, third, fourth, fifth time you’re not really going to see the same thing because the eye is creating sets of images that don’t actually exist.” —John Du Cane, interview with Mark Webber, 2002

LITTLE DOG FOR ROGER

Malcolm Le Grice, 1967, b/w, sound, 13 min

“The film is made from some fragments of 9.5mm home movie that my father shot of my mother, myself, and a dog we had. This vaguely nostalgic material has provided an opportunity for me to play with the medium as celluloid and various kinds of printing and processing devices. The qualities of film, the sprockets, the individual frames, the deterioration of records like memories, all play an important part in the meaning of this film.” —Malcolm Le Grice, Progressive Art Productions distribution catalogue, 1969

“The strategy of minimizing content to intensify the perception of film as a plastic strip of frames is explicitly demonstrated in Le Grice’s seminal Little Dog For Roger. Here the 9.5mm ‘found-footage’ of a boy and his dog is repeatedly pulled through the 16mm printer; the varying speed and swaying motion of the original filmstrip ironically allude to the constant speed and rigid registration of the 16mm film we are watching, and develop a tension between our knowledge of the static frames which comprise the filmstrip and the illusion of continuous motion with which it is imbued. The use of ‘found-footage’ and of repetition – which threatens endlessness, though this is a relatively short film – owe something to the ‘pop’ aesthetic then dominant, but the spectator is never permitted to complacently enjoy these found-images; the graininess and under-illumination, the negative sequences and upside-down passages are designed not so much to add variation as to continuously render those simple images difficult to decipher, thus stressing that very act of decoding. The relentless asceticising of the image became a major preoccupation in subsequent British avant-garde filmmaking.” —Deke Dusinberre, Perspectives on British Avant-Garde catalogue, 1977

DECK

Gill Eatherley, 1971, colour, sound, 13 min

“During a voyage by boat to Finland, the camera records three minutes of black and white 8mm of a woman sitting on a bridge. The preoccupation of the film is with the base and with the transformation of this material, which was first refilmed on a screen where it was projected by multiple projectors at different speeds and then secondly amplified with colour filters, using postive and negative elements and superimposition on the London Co-op’s optical printer.” —Gill Eatherley, Light Cone distribution catalogue, 1997

“Deck was shot on Standard 8, black and white, on a boat going from Sweden to Finland on a trip to Russia. And then I just filmed it off the screen at St Martin’s, put some colour on it, and turned it upside-down … Just turned it upside-down and put some sound on. The sound came off a radio – just fiddling around with a radio and a microphone, just in-between stations. It was one of the longest films I’ve ever made and that kind of frightened me a little bit. I thought it would be too long, you know, 13 minutes was quite a long time. Most of my films are only three minutes, six minutes, eight minutes … but it could have gone on longer maybe…” —Gill Eatherley, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

Back to top

Date: 19 May 2002 | Season: Shoot Shoot Shoot 2002 | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

INTERVENTION & PROCESSING

Sunday 19 May 2002, at 3:00pm

London Tate Modern

The workshop was an integral part of the LFMC and provided almost unlimited access to hands-on printing and processing. Within this supportive environment, artists were free to experiment with technique and engage directly with the filmstrip in an artisan manner. By treating film as a medium in the same way that a sculptor might use different materials, the Co-op filmmakers brought a new understanding of the physical substance and the way it could be crafted.

Annabel Nicolson, Slides, 1970, colour, silent, 12 min (18fps)

Fred Drummond, Shower Proof, 1968, b/w, silent, 10 min (18fps)

Guy Sherwin, At The Academy, 1974, b/w, sound, 5 min

David Crosswaite, The Man With The Movie Camera, 1973, b/w, silent, 8 min

Mike Dunford, Silver Surfer, 1972, b/w, sound, 15 min

Jenny Okun, Still Life, 1976, colour, silent, 6 min

Lis Rhodes, Dresden Dynamo, 1971, colour, sound, 5 min

Chris Garratt, Versailles I & II, 1976, b/w, sound, 11 min

Roger Hewins, Windowframe, 1975, colour, sound, 6 min

Annabel Nicolson pulled prepared sections of film (which might be sewn, collaged, perforated) through the printer to make Slides. Fred Drummond’s Shower Proof, an early Co-op process film, exploits the degeneration of the image as a result of successive reprinting, intuitively cutting footage of two people in a bathroom. Guy Sherwin uses layers of positive and negative leader to build a powerful bas-relief in At The Academy, while Jenny Okun explores the properties of colour negative in Still Life. Considered and brilliantly executed, The Man with the Movie Camera dazzles with technique as focus, aperture and composition are adjusted to exploit a mirror positioned in front of the lens. For Silver Surfer, Mike Dunford refilms individual frames of footage originally sourced from television as waves of electronic sound wash over the shimmering figure. Contrasting colours and optical patterns intensify the illusion that Lis Rhodes’ Dresden Dynamo appears to hover in deep space between the viewer and the screen. Garratt’s Versailles I & II breaks down a conventional travelogue into repetitive, rhythmic sections. Roger Hewins employs optical masking to create impossible ‘real time’ events which, though prosaic, appear to take on an almost sacred affectation in Windowframe.

Screening introduced by Lis Rhodes.

PROGRAMME NOTES

INTERVENTION & PROCESSING

Sunday 19 May 2002, at 3:00pm

London Tate Modern

SLIDES

Annabel Nicolson, 1970, colour, silent, 12 min (18fps)