Date: 12 February 2002 | Season: Andy Warhol Tate

THE FILMS OF ANDY WARHOL

12 February–24 March 2002

London Tate Modern & The Scala

A season of films to accompany the exhibition Warhol, at Tate Modern, 7 February – 1 April 2002, sponsored by UBS Warburg.

Though obsessed since childhood with Hollywood and stardom, it was not until the peak of his fame that Warhol turned his creative energy to film. During an explosive five-year period from 1963–68, he released over 60 films which range from silent, fixed-frame conceptual works through to contemporary commercial ‘sexploitation’ films. His reputation shifted from being the world’s most notorious artist to being the best-known director of ‘underground movies’.

Warhol’s studio, the Factory, was already a meeting place for New York’s artistic elite and underground subculture, and this mixture of high and low society provided a unique repertory of screen characters. Extroverts such Warhol’s assistant Gerard Malanga and the doomed socialite Edie Sedgwick, were brought together with members of New York’s avant-garde film and theatre movements to star in both improvised and scripted films.

The films have gone largely unseen since Warhol withdrew them from circulation in 1972 and this long-overdue season will be a chance to assess their cultural and historical significance. Rising from the fresh explosion of pop art, and crossing the boundaries of entertainment, conceptualism and the avant- garde, the films of Andy Warhol are first class art, and top entertainment.

The Films of Andy Warhol is curated by Mark Webber. With thanks to Callie Angell, Nina Caplan, Al Rees, Michael O’Pray and Silver Smith.

The films of Andy Warhol are distributed by the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Channel 4 will broadcast a new series of three documentaries on Warhol beginning 27 January 2002.

UNPUBLISHED TEXT ON WARHOL’S FILMS

Warhol’s films are shrouded in misconceptions – you might think you don’t need to see the films after hearing the title but that’s like having someone describe a piece of art and not seeing it for yourself. Seeing a still for a film, or a clip on television is like looking at a poster or postcard of a painting. Until you are able to directly engage with a work of art in the flesh, so to speak, you will never appreciate the qualities of the surface, its intention and depth. It’s lazy to regard Warhol’s films as ‘boring’ – they are vital and alive, with a resonance equal to his most impressive or well-known paintings. The confusion is compounded by the fact that the films have been seldom available for viewing. Like the greatest works of art, Warhol’s films must be experienced and engaged with; they succeed not only on an intellectual level but also as entertainment.

The films have a clear cultural and historical significance, rising from the fresh explosion of pop art, crossing the boundaries of conceptualism, entertainment and the avant-garde. The passage of time has revealed that Warhol’s stare was not one of benign passivity, nor was he a cold, hard manipulator. There is a keen eye for cinema, a remarkable ability to articulate a unique vision that sustains its ability to engage the audience. The films maintain the attributes of entertainment, whilst being artistic inquiries into concerns such as duration and representation.

Andy Warhol turned his creative energy to film in 1963, the year of his iconic paintings of Marilyn Monroe and Jackie Kennedy, and a time when his fame and notoriety was at its highest peak so far. He was an artist best known for seemingly mechanical, repetitious works, and recognised that cinema offered the opportunity to reproduce images 16 or 24 times per second. Since his childhood he had been obsessed with Hollywood and stardom, so it seems almost inevitable that he would want to produce his own films, and later range beyond the initial artistic context.

His studio, the Factory, had already become a meeting place for New York’s artistic elite and underground subculture, and this mixture of high and low society provided the repertory of characters from which he was able to populate his films. Natural extroverts from his immediate circle, such as his assistant Gerard Malanga and doomed socialite Edie Sedgwick, were brought together with those from the already active avant-garde film and theatre movements and were encouraged and empowered to appear in both improvised and unscripted experimental works.

During an incredibly productive five-year period, Warhol rediscovered the development and sophistication of film technique, progressing from silent, fixed-frame conceptual works through to contemporary commercial “sexploitation” films. His reputation shifted from being the world’s most notorious artist to being the best-known director of “underground movies”. Whilst his practise was rooted in the avant-garde, it’s important to assert that he was also drawing inspiration from Hollywood, theatre and documentary film.

After the assassination attempt by Valerie Solanas in 1968, Warhol soon withdrew from direct involvement in film production. Paul Morrissey assumed the directorial role of Factory Films, building on the box office success of the experimental double-screen film The Chelsea Girls, which had played in commercial theatres. Morrissey shifted the emphasis to producing more conventional movies such as the Flesh, Trash and Heat trilogy. Ironically, it is this work that has been screened most often while the true hardcore of Warhol’s cinema has remained out of view.

Andy Warhol’s films have a reputation based largely on a small but influential canon of writing, which itself dates mainly from around 30 years ago. The films have gone largely unseen since Warhol withdrew them from circulation in 1972. Even up to that point, few had been seen in England. After his death in 1987, the Andy Warhol Film Project was founded to research and restore this neglected area of his artistic output, and to make the films available again. Aside from sporadic screenings, there has been no real opportunity to re-evaluate or confront the films in the UK. This season offers a valuable chance to view a significant collection of works, and will surely demonstrate their lasting values.

Mark Webber, 2001

Back to top

Date: 12 February 2002 | Season: Andy Warhol Tate

KISS + SOAP OPERA

Tuesday 12 February 2002, at 6:30pm

London Tate Modern

Two early episodic films: unreal erotic slow motion and daytime tv for night-time people.

Andy Warhol, Kiss, USA, 1963, 54 min

Andy Warhol, Soap Opera, USA, 1964, 46 min

Two episodic films which illustrate Warhol’s unique early cinematic style. His silent movies were shot at sound speed and screened one-third the pace, imparting an unreal, poetic/erotic slow motion. Kiss is a series of high contrast, static shots of couples kissing, each lasting the length of a roll of film. Warhol experiments with the soap opera format by punctuating his own dramatic sequences with actual television commercials.

Date: 17 February 2002 | Season: Andy Warhol Tate

EAT + HENRY GELDZAHLER

Sunday 17 February 2002, at 3:00pm

London Tate Modern

Minimal portraits of figures from the New York art world.

Andy Warhol, Eat, USA, 1964, 39 min

Andy Warhol, Henry Geldzahler, USA, 1964, 99 min

Two slow motion, minimal portraits of figures from the New York art world. Artist Robert Indiana eats, and the former curator of the Metropolitan Museum of Art smokes a cigar. Eat consists of several short rolls assembled out of order so the consumed mushroom occasionally renews itself. During the course of his extended portrait Geldzahler’s initial poise descends into discomfort and self-consciousness.

Date: 19 February 2002 | Season: Andy Warhol Tate

BLOW JOB + HORSE

Tuesday 19 February 2002, at 6:30pm

London Tate Modern

The Factory as haven and outlet for homosexual expression.

Andy Warhol, Blow Job, USA, 1963, 41 min

Andy Warhol, Horse, USA, 1965, 100 min

Warhol’s Factory provided both a haven and outlet for overt homosexual expression. The notorious (but inoffensive) Blow Job is a single sustained close-up of an anonymous boy’s face as someone, out of camera range, performs fellatio on him: all of the action takes place below the frame. Horse exposes the machinery of cinema as the lights, microphone and studio surroundings remain in shot. The film foreshadows Lonesome Cowboys (1967-68) as a camp parody of the western, revealing the genre’s concealed homoeroticism.

Date: 24 February 2002 | Season: Andy Warhol Tate

HARLOT + SCREEN TEST #2

Sunday 24 February 2002, at 3:00pm

London Tate Modern

Early sound films from the Silver Factory.

Andy Warhol, Harlot, USA, 1964, 67 min

Andy Warhol, Screen Test #2, USA, 1965, 67 min

Harlot was Warhol’s first sound film, but subversively the sound is disconnected and consists of an out of frame discussion between Ronald Tavel, Billy Name and English poet Harry Fainlight. On screen four superstars (and a cat) eat bananas in an exotic tableaux vivant. Tavel directs Screen Test #2, commanding the transvestite star Mario Montez, who executes a tragic but convincing performance in the face of mockery and scorn.

Date: 3 March 2002 | Season: Andy Warhol Tate

CAMP + PAUL SWAN

Sunday 3 March 2002, at 3:00pm

London Tate Modern

Thoroughly Modern Vaudeville.

Andy Warhol, Camp, USA, 1965, 67 min

Andy Warhol, Paul Swan, USA, 1965, 66 min

Paul Swan, a pioneer of modern dancing who had been frequently billed “the most beautiful man in the world”, performs for the camera in his twilight years. His tragi-comic film brings to mind the uncompromising theatrical productions of Jack Smith. Both appear in Camp, an incredible underground variety show that also stars Baby Jane Holzer, Tally Brown, Mario Montez and Gerard Malanga.

Date: 5 March 2002 | Season: Andy Warhol Tate

BEAUTY #2 + SPACE

Tuesday 5 March 2002, at 6:30pm

London Tate Modern

Scenes from the life of Edie Sedgwick.

Andy Warhol, Beauty #2, USA, 1965, 66 min

Andy Warhol, Space, USA, 1965, 67 min

Further portraits of socialite and muse Edie Sedgwick. In Beauty #2 she auditions a new boyfriend as an off-screen acquaintance provokes her with snide comments and questions, initiating a complex psychological situation. Space begins with a planned scenario in which different characters read eight unconnected scripts, but soon degenerates into casual talk, food fights and folk singing.

Date: 10 March 2002 | Season: Andy Warhol Tate

VINYL + MY HUSTLER

Sunday 10 March 2002, at 3:00pm

London Tate Modern

Factory favourites starring Gerard Malanga and Paul America.

Andy Warhol, Vinyl, USA, 1965, 66 min

Andy Warhol, My Hustler, USA, 1965, 67 min

Based on an interpretation of Anthony Burgess’ novel “A Clockwork Orange”, Vinyl has a claustrophobic, sado-masochistic script by Ronald Tavel. Gerard Malanga undergoes reconditioning for his transgressions as a juvenile delinquent. My Hustler is a first attempt at a more commercial film, with some concession towards conventional techniques. A sexual triangle competes for the attention of Paul America, a young stud ordered from the Dial-A-Hustler service.

Date: 12 March 2002 | Season: Andy Warhol Tate

SUNSET + IMITATION OF CHRIST

Tuesday 12 March 2002, at 6:30pm

London Tate Modern

Sections from the 25-hour double screen movie ****.

Andy Warhol, Sunset, USA, 1967, 33 min

Andy Warhol, Imitation of Christ, USA, 1967-69, 85 min

Warhol’s recording of a beautiful California sunset was one of an unfinished series commissioned by art patrons Jean and Dominique de Menil, and visually echoes their Rothko Chapel. Nico reads poetry on the soundtrack. Imitation of Christ is a domestic comedy about a strange but beautiful young man who wanders through life oblivious to the complaints of his parents (Ondine and Brigid Polk) and the attempted seductions of his maid (Nico), his girlfriend (Andrea “Whips” Feldman) and the riotous antics of Taylor Mead. Edited down to feature-length from the 6-hour version included in Warhol’s 25-hour double screen film **** (1967).

Date: 17 March 2002 | Season: Andy Warhol Tate

POOR LITTLE RICH GIRL + LUPE

Sunday 17 March 2002, at 3:00pm

London Tate Modern

At home with Edie Sedgwick.

Andy Warhol, Poor Little Rich Girl, USA, 1965, 33 min (double screen)

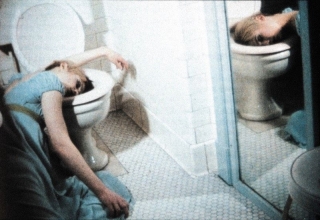

Andy Warhol, Lupe, USA, 1965, 73 min

Warhol spoke of filming twenty-four hours in the life of Edie Sedgwick and these two films may have formed part of the project. Each shows the 1965 Girl of the Year at home, waking up, applying make-up, getting dressed. One reel of Poor Little Rich Girl is inexplicably, but doubtless intentionally, out of focus. Lupe, shot in sumptuous colour, alludes to a re-enactment of the tragic death of actress Lupe Velez, as Edie ends each reel slumped over a toilet bowl.