Date: 2 October 1999 | Season: Dublin Fringe Festival 1999

IN DREAMS: SURREALISM AND TRANCE FILMS

Saturday 2 October 1999, at 1:10pm

Dublin Irish Film Centre

René Clair, Entr’acte, France, 1924, 23 min

Entr’acte, one of the first avant-garde films, was originally made as an interlude to a ballet by Erik Satie. Using a variety of innovative camera tricks, René Clair developed new techniques to illustrate the Dada script by artist Francis Picabia. Free of logic, the film depicts an absurd chase after a runaway hearse.

Maya Deren, Meshes of the Afternoon, USA, 1943,18 min

The making of Maya Deren’s first film was a key point in the advancement of the personal film. It is one of the earliest ‘trance’ films, a style which developed from the earlier European Surrealist films of the 1920s and 30s. Deren creates a subconscious world and portrays a dreamer disturbed by a series of irrational incidents.

Kenneth Anger, Fireworks, USA, 1947, 14 min

Anger made this homosexual psychodrama at the age of 17, using old navy film stock, one weekend while his parents were away from home. It follows a wandering adolescent “drawn through the needle’s eye” of a nightmare dream.

Sidney Peterson, The Lead Shoes, USA, 1949, 15 min

Amid images distorted by anamorphic lenses, mother tries to rescue her son, who is dead in a diving suit. On the fragmented soundtrack a loose jazz group improvises and mixes up two traditional ballads. Sidney Peterson was at the vanguard of the American avant-garde film wave.

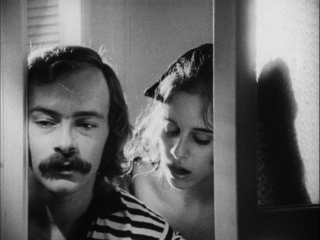

Stan Brakhage, Reflections on Black, USA, 1955, 12 min

Stan Brakhage is regarded by many as the master of experimental cinema. In Reflections on Black, the visions of a blind man depict an erotic and aesthetic quest, which transcends the distinction between fantasy and reality. This angst-ridden drama of relationships in a New York tenement building is an early example of Brakhage’s rejection of sound, which he believes interferes with the purity and clarity of vision.

Back to top

Date: 2 October 1999 | Season: Dublin Fringe Festival 1999

THUNDERCRACK!

Saturday 2 October 1999, at 6:30pm

Dublin Irish Film Centre

Curt McDowell, Thundercrack!, USA, 1975, 158 min

Starring George Kuchar, Marion Eaton and Melinda McDowell

It reads like any classic horror story – a group of teenagers break down in the woods and are forced to spend the stormy night in an eerie, dark house – but from the outset it is clear that this is no ordinary movie, and by the time the sexually active gorilla appears, the audience is clearly in uncharted, perhaps unwanted, territory. This legendary cult film combines George Kuchar’s incredible sense of melodrama with sequences of hard-core sexual fantasy to make the underground’s only pornographic horror blockbuster. Legend tells that Kuchar wrote the script while high on LSD during a thunderstorm in Nebraska, but with true Kucharian pathos it was actually written during a stay at the YMCA in Oklahoma. The film’s director, Curt McDowell, was George Kuchar’s first student at the San Francisco Art Institute, where he still teaches to this day. Having already become a legendary figure in the New York underground film movement, known for classics like Hold Me While I’m Naked and Eclipse of the Sun Virgin, Kuchar moved out to California in 1971 and accepted the teaching post offered to him by filmmaker Larry Jordan. In 1973, McDowell starred in Kuchar’s epic The Devil’s Cleavage, and to return the favour to his favourite student, George wrote, did the lighting and make-up and played a leading role in Thundercrack!. The film was produced by two other students, John and Charles Thomas, partial heirs to the Burger King fortune.

Marion Eaton plays Gert Hammond, sole occupant of the decrepit “Prairie Blossom” mansion house, whose only friend is the bottle since her husband Charlie was devoured by locusts. His remains are kept pickled in the basement, while their sexually deviant son, recently returned from Borneo and suffering from elephantitis of the scrotum, is kept locked in a secret room. On this particular dark and stormy night Gert plays hostess to two sets of strangers – a group of youngsters seek shelter and wind up confronting their own peculiar sexual demons, and later George Kuchar enters as “Bing”, a carnival gorilla keeper who has survived a suicidal attempt to crash his truck. Kuchar’s overwrought melodramatic dialogue which drives the film makes it quite unlike any other movie in the old dark house genre.

While it gained several good reviews on its release, even in staid publications like Britain’s Sight And Sound, Thundercrack! is perhaps just too far out to gain the box office success achieved by similarly trashy features by John Waters, or even Ed Wood. It was a success on the American midnight movie circuit of the late 1970s, but since then has only rarely been seen in cinemas. Only four prints, each of varying lengths, survive and the one presented tonight is the complete 158 minute version. Pushing 3 hours, many people regard the film as an ordeal or endurance test, but sit back and relax (it’s one minute shorter than Eyes Wide Shut!) and enjoy a true, unadulterated Cult Movie. McDowell, Kuchar and leading lady Marion Eaton were reunited for the long and troubled production Sparkle’s Tavern, a less explicit but equally vulgar and deranged film, which took eight years to complete between 1976 and 1984.

Please Note: Thundercrack! is suitable only for mature adult audiences and contains scenes that some people may find offensive.

Back to top

Date: 3 October 1999 | Season: Dublin Fringe Festival 1999

GOING UNDERGROUND: THE NEW AVANT-GARDE

Sunday 3 October 1999, at 1:10 pm

Dublin Irish Film Centre

Bruce Conner, A Movie, USA, 1958, 12 min

Assemblage artist Bruce Conner conceived his first film as a loop forming part of a sculpture. A Movie edits together material from various sources to suggest a continuity where one cannot plausibly exist. Widely regarded as one of the masters of experimental cinema, and a direct influence on TV commercials and pop videos, Conner rarely shoots his own material, preferring to montage found or stock footage.

Robert Nelson, Oh Dem Watermelons, USA, 1965, 12 min

A classic underground romp starring the San Francisco Mime Troop and a dozen watermelons. The fruit is put through every possible use and treatment for comic effect and social comment. Minimalist composer Steve Reich arranged the soundtrack.

Ken Jacobs, Little Stabs at Happiness, USA, 1959-63, 15 min

Little Stabs at Happiness consists of several unedited camera poems which depict a wistful nostalgia for times passed. Two sections feature the legendary filmmaker and performer Jack Smith. Ken Jacobs went on to be an important influence on the Structural movement and since the 1970s has developed amazing 3D projection performances known as the Nervous System.

Joyce Wieland, 1933, Canada, 1967, 5 min

Canadian filmmaker Joyce Wieland was one of the pioneers of the Structural film movement. 1933 is a formal fixed view from a window above a street. Harsh and playful, the film has such a timeless quality it looks as though it could have been made over a hundred years ago.

Michael Snow, Standard Time, Canada, 1967, 8 min

Made as a study for <—>, a film that uses an unrelenting ‘back and forth’ pan to further investigate space in the style of his continuous zoom in Wavelength. For Standard Time the camera roams freely around a small room before settling on an unexpected subject.

Jonas Mekas, Award Presentation to Andy Warhol, USA, 1964, 12 min

Mekas, the irrepressible force behind the promotion and preservation of experimental film, is also known for his rapid-fire diary films. Award Presentation to Andy Warhol documents Mekas giving Warhol (and Factory superstars Gerard Malanga, Baby Jane Holzer and Ivy Nicholson) the Film Culture Sixth Independent Film Award. In contrast to his regular shooting style, Mekas, assisted here by Gregory Markopoulos, uses one long take to replicate Warhol’s own techniques.

George Kuchar, Hold Me While I’m Naked, USA, 1966, 15 min

The Kuchar Brothers’ films are no-budget homages to Hollywood, which depict their own mundane lives as glamorous Technicolor dramas. Hold Me While I’m Naked is a hilarious parody of the frustration and loneliness of a Bronx filmmaker who thinks everyone is having a more exciting, sexier time than he.

Anthony Balch, Towers Open Fire, UK, 1963, 10 min

Towers Open Fire is the most accomplished collaboration between Balch and author William Burroughs. Loosely based on the novel “The Nova Express”, it uses film to illustrate the cut-up writing process.

Owen Land (formerly known as George Landow), New Improved Institutional Quality, USA, 1976, 10 min

Land’s films often use humour and formal technique to question the relationship between the filmmaker, the film and the audience. New Improved Institutional Quality is an absurd IQ test which mocks the illusions of cinema by disregarding senses of scale and rational conception.

Bruce Baillie, All My Life, USA, 1966, 3 min

A single pan across a white picket fence on a clear summer’s day is accompanied by the Billie Holliday song. All My Life is a perfect film which condenses a complete statement in a single shot.

Back to top

Date: 15 October 1999 | Season: Leeds Film Festival 1999

AMERICAN UNDERGROUND PRIMER

Leeds International Film Festival

15 & 16 October 1999

The “American Underground Primer” is intended as a short introduction to the beauty and wonder of American experimental films. The wide-ranging “underground” classification covers many diverse styles including abstract, non-objective, structural, flicker, beat, poetic, personal, animated, diary and low budget films.

Avant-garde film production entered a golden age in 1943 with Maya Deren’s pioneering trance film Meshes Of The Afternoon, and this period of intense production ran through to the mid-1970s when structuralism became the predominant form. During this time numerous advances were made in the theories and techniques of personal filmmaking. These works have proved highly influential to feature film directors from Martin Scorsese through to Harmony Korine, and their inventiveness has informed the methods used in advertisements and pop videos.

With the explosion of “underground” film in the 1960s, the ability to make movies was extended to everyone and during this free thinking period many classics of the genre were made. It should be noted that though these little movies were produced with small or non-existent budgets they are still wildly innovative, entertaining and are eminently watchable by everyone, and should not be restricted to film buffs, students or weirdos.

The American Underground Primer programmes are curated by Mark Webber.

Back to top

Date: 6 May 2000 | Season: Oberhausen 2000 | Tags: Oberhausen Film Festival

CAME THE LOOP BEFORE THE SAMPLER

Saturday 6 May 2000, at 10:00pm

Oberhausen Lichtburg Filmpalast

A film programme conceived as a celebration of the loop in its purest form, from the days before its inherent, repetitive beauty was abused by the talent-challenged masses of modern musicians. I oppose the use of drum loops and sampled sections “borrowed” from other people’s hard work in order to compensate for an individual’s lack of creativity. Imitation is the highest form of flattery, but only if it is done in an intelligent manner. There are clever (and respectful) ways in which to quote someone else’s material that bears no relation to using another’s talent to counteract your lack of imagination. The programme is partially conceived as an audio / visual assault on the sample-mongers, but in turn provides divine retribution for those of who appreciate the loop in it’s absolute, most crafted form.

Robert Nelson, Oh Dem Watermelons, 1965, 12 min

Peter Kubelka, Adebar, 1956-57, 1.5 min

Anthony Balch & William Burroughs, The Cut-Ups, 1967, 10 min

Keewatin Dewdney, The Maltese Cross Movement, 1967, 8 min

Joyce Wieland, 1933, 1967, 4 min

Owen Land (formerly known as George Landow), Thank You Jesus for the Eternal Present: 1, 1973, 6 min

Chris Garratt, Exit Right, 1976, 5 min

Standish Lawder, Runaway, 1969, 6 min

Malcolm Le Grice, Reign of the Vampire, 1970, 15 min

Bruce Conner, Looking for Mushrooms, 1961-67/1995, 14 min

Note: Although it was only announced as the second film in the programme, Adebar by Peter Kubelka was projected eight times, between all the other films.

PROGRAMME NOTES

CAME THE LOOP BEFORE THE SAMPLER

Saturday 6 May 2000, at 10:00pm

Oberhausen Lichtburg Filmpalast

OH DEM WATERMELONS

Robert Nelson, USA, 1965, 16mm, colour, sound, 12 min

The soundtrack to Oh Dem Watermelons was created by Steve Reich, who is now recognised as one of the first composers to use tape loops, and short repetitive phrases, in “serious” (modern classical) music. To accompany the film, Reich took a parody of a Stephen Foster song and wrote a loop into the melody. The resulting score, which is sung by a chorus of voices, repeats the “Watermelon” in the lyric in a manner which mirrors the repetitive treatment of the unfortunate fruits on the screen.

“The film cost $280 to make, including the cost of a dozen watermelons. We all had a good time running around the Mission District and Portrero Hill busting up watermelons, showing-off and having fun. A few weeks later when we had the film roughly edited, I ran it silent for Ron and Saul and a few people at the Mime Troupe. There was deadly silence and it looked awful. Everyone was embarrassed for me and didn’t know what to say. I faked it by saying it was good and not to worry. A few days later Steve Reich composed the soundtrack and got all the people to sing their parts the right way. The track has helped the film a lot. The film has won a lot of prizes all over the world … and I bought a lot of equipment with the prize money I got for it.” (Robert Nelson)

ADEBAR

Peter Kubelka, Austria, 1956-57, 35mm, b/w, sound, 1.5 min

The spectator of Peter Kubelka’s Adebar benefits greatly from repeated viewing. In fact, the filmmaker distributes both this and the related work Schwechater (1957-58), on reels containing two, five, or seven successive prints. These two short films present a highly refined, economical use of sound and image that are intricately measured against each other. To construct Adebar, Kubelka devised five self-imposed rules regarding the sequencing of the eight chosen sections (of which six have movement and two are stills) and applied these rules to the editing process. The integrated soundtrack is assembled from four twenty-six frame phrases of Pigmy music.

“In the attempt to find for film binding compositional principles of a syntactical-formal nature, Kubelka proceeds in a way analogous to music, especially Webern’s. Filmic time was conceived as ‘measurable’ in the same way as musical time; tones as ‘time-points’ became the frames of film. Just as Webern reduced music to the single tone and the interval, so Kubelka reduced film to the film-frame and the interval between two frames. Just as the law of the row and its four types determined the sequence of tones, pitches, etc., so now the sequence of frames, and of the frame-count, phrases in Vertov’s terminology, positive and negative, timbre, emotional value, silence, etc; between these factors as in serial music, the largest possible number of relationships were produced. It was for this reason that Kubelka also called these films ‘metrical films’. For the metrication of the material already established in Mosaik Im Vertrauen now became a metrication of the single frames. It passed over, so to speak (as with Webern) from the thematic organisation to the organisation of the row, and like the latter he viewed the number opf frames as a function of intervals. Adebar, a film commissioned by the bar of the same name, is the first pure Viennese formal film to be generated by these considerations.” (Peter Weibel)

THE CUT-UPS

Anthony Balch & William Burroughs, UK, 1967, 16mm, b/w, sound 10 min

The Cut Up technique, which was developed for literature by William Burroughs and Brion Gysin, was adapted and applied to film by Anthony Balch. The footage was originally shot in 1961-65 for an uncompleted film called Guerrilla Conditions, and was subsequently edited intor four separate sequences. After determining an optimum length of shot that would allow a viewer to recognise imagery without being able to interpret it, Balch instructed a lab technician to “take a foot from each roll and join them up”, making this an early (and unrecognised) Structural film. As with Oh Dem Watermelons, the soundtrack of The Cut Ups relies more on a written score than it does on a looped tape. Burroughs and Gysin read the well orchestrated, persistent text, which is based on a Scientology manual.

“The Cut Ups was a radical cinematic experiment; primarily this was due to its re-negotiation of the ontology of film. The process of viewing The Cut Ups is analogous to the process of viewing the Dreamachine; like the Dreamachine the film creates a rhythmic pattern of flickering light and images across the audience’s retinas; as Ian Sommerville noted, “Flicker may play a part in cinematic experience. Films impose external rhythms on the mind, altering the brain waves which are otherwise as individual as finger-prints”. The Cut Ups presented images which were simultaneously at random, yet precise, with scenes structured according to lengths of celluloid rather than of action or narrative. The only order imposed on the film is that which attempts to remove coherent, linear, narrative structure. The film demands that an audience experience film differently: as pure light and motion. Devoid of ‘rational logic’, conventional narrative, and recognisable visual pleasure; instead The Cut Ups constructs the audience’s relation with film as one based on the aesthetic of pure speed, as images strobe past the audience’s collective retina.” (Jack Sargeant)

THE MALTESE CROSS MOVEMENT

Keewatin Dewdney, Canada, 1967, 16mm, colour, sound, 8 min

A loop of the Beach Boys’ song “Gettin’ Hungry” from the “Smiley Smile” album provides an aural background to this cleverly constructed work by an undervalued Canadian filmmaker. One aspect of the film is concerned with using pictures to visually represent words, in a manner comparable to Associations (1975) by English filmmaker John Smith. As a result of the reorganisation of fragments of sound and imagery from throughout the film, the viewer suddenly becomes aware of an emerging objective, which triumphantly comes together in the final montage.

The film reflects Dewdney’s conviction that, “the projector, not the camera, is the filmmaker’s true medium”. The form and content of the film are shown to derive directly from the mechanical operation of the projector – specifically the animation of the disk and the cross illustrates graphically (no pun intended) the projector’s essential parts and movements. It also alludes to a dialectic of continuous-discontinuous movements that pervades the apparatus, from its central mechanical operation to the spectator’s perception of the film’s images … [His] soundtrack demonstrates that what we hear is also built out of continuous-discontinuous ‘sub-sets’. The film is organised around the principle that it can only complete itself when enough separate and discontinuous sounds have been stored up to provide the male voice on the soundtrack with the sounds needed to repeat a little girl’s poem; “The cross revolves at sunset / The moon returns at dawn / If you die tonight / Tomorrow you’re gone.” (William C. Wees)

1933

Joyce Wieland, Canada, 1967, 16mm, colour, sound 4 min

In striving to interpret the basic visual element of “1933”, scholars have often refused to accept that it may just be a repeated segment of unpretentious, interesting, footage. The film presents an astute, casual view of the street below which certainly throws up some interesting spatial considerations, but Wieland’s real skill was in the shrewd looping, the changes of pace, the mysterious superimposition and the uncompromising soundtrack. In many ways, “1933” seems more like a sculpture that a film. It’s easy to imagine it continually rolling, and not only coming to life when projected.

“While the superimposed title in Sailboat (also 1967) literalizes itself through the images, the title “1933” does nothing of the kind. Joyce Wieland commented that one day after shooting she returned home with about thirty feet of film remaining in her camera and proceeded to empty it by filming the street scene below. She explains in notes: “When editing what I then considered the real footage I kept coming across the small piece of film of the street. Finally I junked the real film for the accidental footage of the street. It was a beautiful piece of blue street … So I made the right number of prints of it plus fogged ends”. The street scene with the white-streaked end is loop-printed ten times, and “1933” appears systematically on the street scene for only the first, seventh and tenth loops. While the meaning of the title, 1933, is enigmatic and has no real and ostensible relationship to the film, in its systematic use as subtitle it becomes an image incorporated into the feel. And in that sense it reaffirms the film itself. It is not the title of a longer work, but an integral part of the work.” (Regina Cornwell)

THANK YOU JESUS FOR THE ETERNAL PRESENT: 1

Owen Land (formerly known as George Landow), USA, 1973, 16mm, colour, sound, 6 min

The soundtrack of Land(ow)’s Thank You Jesus For The Eternal Present: 1 is based upon recordings of conversations with devoted Christians, making it the first film of his directly concerned with Christian subject matter. Only a few discernible phrases are heard as much of these recordings are obscured by a loop of a female voice religiously (or sexually ?) intoning “Oh God, Oh God, Oh God, Oh God”, these sounds being clearly related to the woman’s ecstatic face which is superimposed over the basic footage. Land claims that Thank You Jesus is a series of which only this first segment has been completed.

“Thank You Jesus For The Eternal Present posits, in ingeniously compact visual / aural form, a multitude of eternal dichotomies, among them darkness and light, and the psychic separation of spiritual / sexual (inward) versus material / sexual (outward) striving. Instead of a yin / yang antimony: God and the Devil in female guise. The fervently whispered prayers of the woman whose face is seen in close up have transported her to a nearly sexual, religious ecstasy; and each reappearance of the worldly, sexually powerful ‘corporation’ woman is heralded by a sharp, synchronous thunderclap and camera flash. Yet it is she – the world woman, Venus in Furs – full colour, in glory, who nods in assent, in sole possession of the screen at film’s end.” (John Luther Schofill)

EXIT RIGHT

Chris Garratt, UK, 1976, 16mm, b/w, sound, 5 min

The early films of Chris Garratt frequently use looping and staggered progressions such as two-steps-forward-one-step-back. This kind of editing scheme is best demonstrated in Romantic Italy (1975), which reassembles a found travelogue depicting the historic city of Florence using a schedule of 1234234534564567…etc., utterly deconstructing the original passage of the footage while keeping it in order. Exit Right deals with two of the main concerns of English filmmaking in the mid-1970s – an investigation of printing techniques (the London Co-operative had its own home made, much used, optical and contact printers), and the visual creation of sound by printing images over the optical track (Guy Sherwin, Lis Rhodes and many others investigated this possibility).

“A one second shot of me walking into the shot wearing a striped jersey was printed repeatedly; this strip of negative was moved laterally across the printer every ten seconds of film time, so that the image of the piece of film material, containing its figurative image moves into the projected frame from the left, across the frame and out across the optical soundtrack area to the right. Featuring a New Line in musical pullovers.” (Chris Garratt)

RUNAWAY

Standish Lawder, USA, 1969, 16mm, b/w, sound, 6 min

For Runaway, Lawder took four seconds of a commercial animation called The Fox Hunt and made a continuous loop that was re-photographed and sequentially abstracted so the cartoon dogs seem unable to escape the frame. The humorous display of visual techniques is accompanied by a jaunty organ track, which is restrained in a manner similar to the dogs before being allowed to progress to its conclusion. Runaway is a successful early attempt to integrate the developing video technology into contemporary film practice.

“A cartoon image of dogs rushing across the screen, then reversing their direction, is looped over and over, to the accompaniment of a sprightly tune played on an organ. The footage is seen on television, then as film, then back on TV, deteriorating and recovering clarity as the repetitions roll on. [Lawder] achieves the perfection of all his techniques in a small film called Runaway, in which he uses a few seconds of cartoon dogs chasing a fox. By stop motion, reverse printing, video scanning, by manipulating a few seconds of an old cartoon, he creates a totally new and different visual reality that is no longer a silly, funny cartoon. He elevates the cartoon imagery to the visual strength of an old Chinese charcoal drawing.” (Jonas Mekas)

REIGN OF THE VAMPIRE

Malcolm Le Grice, UK, 1970, 16mm, b/w, sound, 15 min

While the repetitious images in Reign Of The Vampire are clearly assembled systematically, the strategy is not necessarily perceptible to the audience. Le Grice has stated that appreciation of the system is kinetic rather than intellectual. The continuous, subtle changes of the loops appear more closely suitable for brainwashing than as material for rational interpretation. When these images are coupled with a similarly relentless, slowly evolving soundtrack, the overall effect is one of cerebral subversion.

“This film could be considered as a synthesis of the “How To Screw The C.I.A.” series. It is formally based on the permutive loop structure, superimposing a series of three pairs of image loops of different lengths with each other. The images include elements from all the previous parts of the series. The film sequences, which make up loops, are again chosen for their combination of semantic relationships, and abstract factors of movement. The soundtrack is constructed for the film, but independently, and has a similar loop structure.” (Malcolm Le Grice)

LOOKING FOR MUSHROOMS

Bruce Conner, USA, 1961-67/1995, 16mm, colour, sound, 14 min

In its present form, Looking For Mushrooms is a new realisation of two previous works that used the same title and contained the same intense barrage of footage. This highly edited reel is a combination of material shot in San Francisco in 1959, and during a trip to Mexico two years later. The film was first exhibited in 1965 as a silent fifty foot 8mm reel projected at a speed of 5fps and lasting eleven minutes. In 1967, the same film was released on 16mm (at 24fps) with a soundtrack of “Tomorrow Never Knows” from The Beatles’ “Revolver” album. Nearly thirty years later, Conner took this and another slow-speed 8mm reel, Report: Television Assassination (1963-64) – a different, but related, work to Report (1963-67) – and step printed them both onto 16mm using a frame ratio of 5:1. This new version of Looking For Mushrooms was accompanied by a recording of “Poppy Nogood and the Phantom Band” by Terry Riley, a composer who took the process of tape looping to new, unequalled heights with his music in the late 1960s. From the “Rainbow In Curved Air” album, through his all night concerts, to his organ improvisations of the 1970s, Riley refined a technique of combining solo live performance with his own system of real time tape looping that puts today’s musicians and technology to shame.

“Looking For Mushrooms unfolds at one and the same time as a hyperactive, realistic recording – a travel diary – and as a freewheeling, almost hallucinatory spectacle. The arc of the film’s structure suggests a shift from the material world shown in great detail to a purely ideational realm of art. What reconciles these seemingly contradictory zones is Conner’s mediating sensibility … In 1995, Conner revised Looking For Mushrooms, [which was] step-printed and slowed down by a factor of five, and given a new score. The film gained a heightened level of visibility through a pacing that restrained the abstracting speed of the original shooting, cutting, and superimposition; and it acquired a potent acoustic counterpoint through the addition of a performance by Terry Riley that highlights the microrhythms of Conner’s masterful camera work and complex montage.” (Bruce Jenkins)

Back to top

Date: 2 July 2000 | Season: Miscellaneous

THE DAY OF RECKONING

Sunday 2 July 2000, at 6:00pm

London Battersea Arts Centre

The night is long and it is hard.

REINDEER SLAUGHTER AT LAKE KRUTVATTNET

Louise O’Konoe, 1967, b/w, silent, 6 min

This film documents the slaughtering of reindeer by Norwegian and Swedish Sami (Lapps) on Lake Krutvattnet in Norway, close to the Swedish border. It records some of the steps involved: driving the herd into the enclosure, catching and killing them (with a knife or bolt gun). (Louise O’Konoe)

LE SANG DES BETES

Georges Franju, 1949, b/w, sound, 20 min

Amidst steaming blood and men wading in excrement, even Vietnam and the concentration camps are not too far away. The killing of animals in Paris slaughterhouses becomes a poetic metaphor of the human condition. When the butcher raises his axe-like tool to stun the animal, the camera stays with him to the bitter end; there is no attempt either to protect or cheat the spectator; we must come to terms with daily slaughter committed in our name. (Amos Vogel)

UNSERE AFRIKAREISE

Peter Kubelka, 1966, colour, sound, 13 min

Peter Kubelka’s savage montage of safari footage was commissioned from him by Austrian tourists. His Unsere Afrikareise documents and subverts the voracious eye. Scraps of folk-song and banal conversation are cut to images of hunted or dead animals, and universal myth (evoked by tourists admiring the moon) is undercut by neo-colonial reality. (A.L. Rees)

DIPLOTERATOGY, OR, BARDO FOLLIES

Owen Land (formerly known as George Landow), 1967, colour, silent, 20 min

A paraphrasing of certain sections of the Bardo Thodal (Tibetan Book of the Dead). The analogy of the film is between the process and the basic operating procedures of the system of which we are all part, sometimes called ‘creation’; the suggestion is that death is not an end but merely the next stage. (George Landow)

THE ACT OF SEEING WITH ONE’S OWN EYES

Stan Brakhage, 1971, colour, silent, 32 min

Stan Brakhage, entering with his camera, one of the forbidden, terrific locations of our culture, the autopsy room. It is a place wherein, inversely, life is cherished, for it exists to affirm that none of us may die without our knowing exactly why. All of us, in the person of the coroner, must see that for ourselves, with our own eyes. (Hollis Frampton)

THE DEAD

Stan Brakhage, 1960, colour, silent, 11 min

A very sombre and intense visual poem, a black lyric full of an open dramatic energy which puts it well above a formal or rhetoric exercise on Time and Eternity. In the visual form of the monuments of the Pere Lachaise cemetery in Paris, the persistent and impenetrable geometric masonry gets to be less a symbol of death than a death-like sensation. (Donald Sutherland)

TIME OF THE LOCUST

Peter Gessner, 1966, black and white, sound, 12 min

A film about the war in Vietnam, compiled from American newsfilm, combat footage shot by the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam and suppressed film taken by Japanese cameramen. Not propaganda but an expression of agony. (Peter Gessner)

MASS (FOR THE DAKOTA SIOUX)

Bruce Baillie, 1964, black and white, sound, 24 min

The Mass is traditionally a celebration of Life; thus the contradiction between the form of the Mass and the theme of death. The dedication is to the religious people (the Dakota Sioux) who were destroyed by the civilisation that evolved the Mass. (Bruce Baillie)

REPORT

Bruce Conner, 1963-67, black and white, sound, 13 min

Society thrives on violence, destruction, and death, no matter how hard we try to hide it with immaculately clean offices, the worship of modern science, or the creation of instant martyrs. From the bullfight arena to the nuclear arena, we clamour for the spectacle of destruction. The crucial link in Report is that JFK was as much a part of the destruction game as anyone else. Losing is a big part of playing games. (David Mosen)

CROSSROADS

Bruce Conner, 1976, black and white, sound, 36 min

Conner bases his film on government footage of the first underwater A-bomb test, July 25, 1946, at Bikini Atoll in the Pacific. The same explosion is seen from the air, from boats and land based cameras. The opening segment emphasises the awesome grandeur; the destructiveness, as well as the dramatic spectacle and beauty. As repetition builds, the explosion is gradually removed from the realm of historic phenomena, assuming the dimensions of a universal, cosmic force. (Thomas Albright)

Film programme compiled by Mark Webber. Thank you David Jubb, Ben Cook, Andrew Youdell and David Leister. Le Sang Des Betes is distributed by the British Film Institute. All other films courtesy of Lux Distribution.

Date: 8 October 2000 | Season: Leeds Film Festival 2000

BRITISH AVANT-GARDE: AN INTRODUCTION TO THE LONDON FILM-MAKERS’ COOPERATIVE

Sunday 8 October 2000, at 5:30pm

Leeds City Art Gallery

In 1966, influenced by the apparent success of the Film-Makers’ Cooperative run by Jonas Mekas in New York, a group of English film devotees came together to form the London Filmmakers’ Coop. At this time, the London art film scene centred on the liberal Better Books store, managed by concrete poet Bob Cobbing. In the basement of the shop, Cobbing mounted exhibitions, happenings and held screenings of early American avant-garde films by Maya Deren, Kenneth Anger, Stan Brakhage and others. Nearby, the UFO and Middle Earth night-clubs also showed underground films to accompany all-night concerts by psychedelic rock groups like The Pink Floyd and Soft Machine.

At first, the London Coop was populated more by viewers than filmmakers, and the distribution collection comprised mainly of films from the USA, which had remained in London after the critic P. Adams Sitney had completed his New American Cinema tour of Europe. Only a few maverick characters such as Jeff Keen and Anthony Balch had made original works free of the conventional BFI Production Board. Following the Coop’s relocation to the Arts Laboratory, which resulted in changes in leading personal, new members of the group began to actively produce films as printing and processing facilities were provided in-house for their use. From this time on, the more anarchic, carefree approach embodied in the films of Steve Dwoskin (an American ex-pat with links to Andy Warhol’s Factory and who’s films featured the New York underground stars), gave way to a more formal style led by fellow countryman Peter Gidal, and former painter Malcolm Le Grice, who both exerted an enormous influence through their innovative work and tireless activities. Exerting his influence on the next wave of filmmakers through screenings, writings and teaching, Le Grice became the leading light of the English avant-garde.

By the early 1970s, hundreds of films were being produced in a variety of personal styles. Access to the coop’s home-made equipment led to much investigation of the film material, as seen in the early films of Guy Sherwin and Lis Rhodes, which directly use the printing process to give the film its form and content. Many English filmmakers, including Mike Dunford and Annabel Nicolson, analysed the possibilities of re-filming projected images, in a similar manner to Ken Jacobs’ Tom, Tom the Piper’s Son (screening on October 14th). Dwoskin used this technique in Dirty, to reinterpret some of his early erotic footage. Le Grice, Gidal, Du Cane and Crosswaite were more in line with the purist Structural film movement, while Breakwell’s Repertory and the films of John Smith (see separate programme), used humour to disguise formal concerns.

After collaborating on the two-screen film River Yar (1972), Chris Welsby and William Raban led a tradition of British landscape film, often using time-lapse photography to portray the environment. Jeff Keen and John Latham were renegades, independent of the Coop community, creating singular works mixing live action and animation. Many of the filmmakers represented in this programme ventured beyond the accepted boundaries of filming to make multi-screen or expanded cinema events.

The LFMC continued to struggle with problems of funding and location until being re-housed in the purpose built facility in 1998. In this more clinical and businesslike environment, the Coop unfortunately lost much of its character and community spirit. Financial problems in recent years led to a merger with London Electronic Arts, a similar organisation representing artists’ video. The Lux Centre for Film, Video and Digital Arts now comprises of a unique cinema, video art gallery and an unparalleled distribution outlet.

Ian Breakwell, Repertory, UK, 1973, 9 min

Guy Sherwin, At The Academy, UK, 1974, 5 min

John Du Cane, Relative Duration, UK, 1973, 10 min

Malcolm Le Grice, Threshold, UK, 1972, 10 min

Peter Gidal, Hall, UK, 1968-69, 10 min

David Crosswaite, The Man With The Movie Camera, UK, 1973, 8 min

William Raban, Angles Of Incidence, UK, 1973, 12 min

Chris Welsby, Park Film, UK, 1972, 7 min

Lis Rhodes, Dresden Dynamo, UK, 1974, 5 min

Stephen Dwoskin, Dirty, UK, 1965-67, 10 min

Jeff Keen, Marvo Movie, UK, 1967, 5 min

John Latham, Speak, UK, 1968-69, 11 min

The programme will be introduced by curator Mark Webber.

Back to top

Date: 13 October 2000 | Season: Ken Jacobs Nervous System

KEN JACOBS RETROSPECTIVE

UK Touring Programme

13 October – 14 December 2000

To accompany the first ever British performances of the amazing Nervous System projections, a three programme retrospective of work by Ken Jacobs, a leading innovator of avant-garde film for the past 40 years.

After making his first films in the late 1950s, Jacobs was at the forefront of the experimental film movement which exploded in New York and across the world throughout the next decade, liberating cinema from its previous restrictions and conventions. The earliest film presented here, The Whirled (1956-61)”, features Jack Smith in a series of vignettes from the period which also yielded the better known and highly influential Little Stabs At Happiness (1958-60) and Blonde Cobra (1959-63), two films considered revolutionary for the way they displayed an entire new cinematic sensibility. Blonde Cobra was particularly radical, containing long scenes of black leader and a soundtrack that incorporates live radio, making no two projections the same.

“Window” (1964) and “Airshaft” (1967) were also unique, showing Jacobs refining his talent for investigating space, an approach rooted in his schooling by abstract expressionist painter Hans Hoffman. With these films Jacobs anticipated the Structural movement, which subsequently became the dominant style of the avant-garde throughout the 1970s, being particularly prevalent among the new English filmmakers.

In 1969, Jacobs made Tom, Tom The Piper’s Son, a 2 hour tour-de-force constructed by re-photographing and dissecting a 10 minute short made by Billy Bitzer in 1905. After presenting the original film, Jacobs pursues a deep analysis into its visual elements; slowing down, freezing action and examining small, abstracted areas of the frame. The film becomes a treatise on composition, an art lesson unfolding before our eyes. Free of narrative, the action becomes the drama. That same year, the filmmaker began to investigate the effects of the Pulfrich pendulum method, in which moving images are given a strong 3D depth. Seen through a Pulfrich filter, the tracking shot of a snowbound suburban housing estate in Globe (1969) becomes an immense vista of shifting planes, tectonic vision of the highest order. The later film Opening The Nineteenth Century: 1896 (1990) re-presents Lumiere footage to similar effect.

The innovation of these works, and experiences directing live action shadow plays, led to the Nervous System, a live projection technique using two specially adapted projectors. Since 1975, Jacobs has developed numerous works that use two identical filmstrips to produce unimagined illusions of depth and perception. Expanding on Muybridge, Marey and the theories of early film, Jacobs unlocks the unknown possibilities hidden deep within cinema, the depth of composition that is usually lost in the unretarded flurry of frames. The Nervous System will receive their British premiere in November at the London Film Festival and selected venues across England.

During his time realising this complex projection set-up, Jacobs continued to investigate other ways of recycling images, calling for “a Museum of Found Footage … a shit-museum of telling discards accessible to all talented viewers/auditors. A wilderness haven salvaged from Entertainment”. His Urban Peasants (1975) marries pre-war home movie footage shot by his wife’s Aunt Stella with a recording of “How To Speak Yiddish”. Perfect Film (1986) presents rushes from TV news footage following the assassination of Malcolm X. The film’s structure fits perfectly alongside his other work, though surprisingly the filmmaker claims to have found the reel in a rubbish bin and considered it “perfect” in its untouched state. In 1978, Jacobs and his students sequentially re-edited The Doctor’s Dream, a bland 1950s television drama to expose an unexpected subtext lurking between gaps in the narrative. His latest films Disorient Express and Georgetown Loop use wide-screen 35mm (by mirror printing standard 16mm) to create abstracted Rorschach images of archival train journeys.

Mark Webber

Film retrospective programmes screening at Leeds International Film Festival (13 & 14 October 2000), Brighton Cinematheque (2 November 2000), Glasgow Film Theatre (7 & 9 October 2000), Hull Screen (30 November & 14 December 2000), Manchester Cornerhouse (4 & 11 December 2000), London Lux Centre (6 & 7 December 2000), Sheffield Showroom (12 December 2000).

Live performances at London Film Festival (3 & 4 November 2000), London Lux Centre (5 November 2000), Oxford Phoenix Picture House (7 November 2000), Manchester Cornerhouse (9 November 2000), Nottingham Broadway (10 November 2000).

Ken Jacobs’ Film Retrospective is a BFI Touring Programme funded by the Arts Council of England and supported by the 44th Regus London Film Festival and Lux Distribution. The season was curated by Mark Webber.

Thank you Sandra Hebron, Tricia Tuttle, Helen De Witt, Emma Heddich, Catharine Des Forges, Joanna Denham, Ben Cook, Ken and Florence Jacobs.

Date: 13 October 2000 | Season: Ken Jacobs Nervous System, Leeds Film Festival 2000

KEN JACOBS RETROSPECTIVE: PROGRAMME 1

Leeds International Film Festival

Friday 13 October 2000, at 6:30pm

INSTRUCTIONS TO AUDIENCE

In order to experience the added depth of the Pulfrich 3D effect, the viewer should use the “Eye Opener” filter during GLOBE. “Flat image blossoms into 3D only when viewer places EYE OPENER © 1987 before right eye. (Keeping both eyes open, of course. As with all stereo experiences, centre seats are bet. Space will deepen as one views further from the screen.)”

PLEASE RETURN YOUR FILTER TO CINEMA STAFF AFTER THE SCREENING

WINDOW

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1964, 16mm, 18fps, colour, silent, 12 min

The moving camera shapes the screen image with great purposefulness, using the frame of a window as fulcrum upon which to wheel about the exterior scene. The zoom lens rips, pulling depth planes apart and slapping them together, contracting and expanding in concurrence with camera movements to impart a terrific apparent-motion to the complex of object-forms pictured on the horizontal-vertical screen, its axis steadied by the audience,s sense of gravity. The camera’s movements in being transferred to objects tend also to be greatly magnified (instead of the camera, the adjacent building turns). About four years of studying the window preceded the afternoon of actual shooting (a true instance of cinematic action-painting). The film is as it came out of the camera, excepting one mechanically necessary mid-reel splice.

(Ken Jacobs, statement in New York Film-Makers’ Cooperative Catalog #5, 1971)

“The careful relationships of planes, textures, and lighting would not lead one to expect such a spontaneous method were it not for the marvellously fluid, active “choreography for camera”. Jacobs continually manipulates focal distance, lighting, and lenses to endow one static space with hundreds of new aspects and directions and speeds of motion.

“Major contrasts, imperceptible in the flow of a continuous viewing, can be seen on closer scrutiny of the film on an analytic projector: contrasts between flat, screen-surface planes and a deeper, textured, more recognisable geography; between geometrically shaped areas of solid black and white and grainier, coloured, reflecting or textured surfaces; between objects which occupy space, such as a water-beaded horizontal sheet of tar paper, a man and woman, a hanging globe, and a statuette and again more abstract, graphic spaces from which shapes often seem cut out; between spaces on a firm, horizontal / vertical axis and those which rotate in and around that axis; and finally between movement and frozen stillness.

“Devices and materials which create the smooth, invisible transitions from shot to shot and space to space are fades done in the camera, changes in focus, backlighting modulating to frontal lighting, a window shutter which opens a slit of light in the shadow before it, and camera movement continuing over the cut. Nearer the end, superimpositions juxtapose in the space of one shot two spaces and times which overlap and define the distance between them. The film presents a few moments of visual beauty in the shifting network of a multitude of frames. Transforming the inert into the moving, Jacobs’ camera travels from form to form with delicacy and grace.”

(Lindley Page Hanlon, excerpt of essay published in “A History of the American Avant-Garde Cinema”, American Federation of Arts, 1976)

AIRSHAFT

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1967, 16mm, 18fps, silent, colour, 4 min

In memory of Judy Midler.

Single fixed-camera take looking out through fire-escape door into space between rears of downtown N.Y. loft buildings. A potted plant, fallen sheet of white paper, and a cat rest on the door-ledge. Cinematographer fingers intercept, deflect, and toy with the flow of light, the stuff of images, on their way to the lens. The flow in time of the image is interrupted, partially and then wholly dissolving into blackness; the picture re-emerges, the objects smear, somewhat double, edges break up. Focus shifts between foreground and background planes, an emphasis of the shaft-space in between. The fragile image shines forth one last time before dying out. Booed at open screening marathon of Vietnam War protest films, “For Life, Against the War.”

(Ken Jacobs, statement in “Films That Tell Time: A Ken Jacobs Retrospective”, American Museum of the Moving Image, 1989)

SOFT RAIN

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1968, 16mm, 18fps, colour, silent, 12 min

View from above is of a partially snow-covered low flat rooftop receding between the brick walls of two much taller downtown N.Y. loft buildings. A slightly tilted rectangular shape left of the centre of the composition is the section of rain-wet Reade Street, visible to us over the low rooftop. Distant trucks, cars, persons carrying packages, umbrellas sluggishly pass across this little stage-like area. A fine rain-mist is confused, visually, with the colour emulsion grain.

A large black rectangle following up and filling to space above the stage area is seen as both an unlikely abyss extending in deep space behind the stage or more properly, as a two dimensional plane suspended far forward of the entire snow/rain scene. Though it clearly if slightly overlaps the two receding loft building walls the mind, while knowing better, insists on presuming it to be overlapped by them. (At one point the black plane even trembles.) So this mental tugging takes place throughout. The contradiction of 2D reality versus 3D implication is amusingly and mysteriously explicit.

Filmed at 24fps but projected at 16fps the street activity is perceptively slowed down. It’s become a somewhat heavy labouring. The loop repetition (the series hopefully will intrigue you to further run throughs) automatically imparts a steadily growing rhythmic sense of the street activities. Anticipation for familiar movement-complexes builds, and as all smaller complexities join up in our knowledge of the whole the purely accidental counter-passings of people and vehicles becomes satisfyingly cogent, seems rhythmically structured and of a piece. Becomes choreography.

(Ken Jacobs, statement in Film-makers’ Cooperative Catalogue #5, 1971)

URBAN PEASANTS

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1975, 16mm, 18fps, b/w, sound on cassette, 50 min

My wife Flo’s family as recorded by her Aunt Stella Weiss. The title is no put down. Brooklyn was a place made up of many little villages; an East European shtetl is pictured here, all in the space of a storefront. Aunt Stella’s camera rolls are joined intact (not in chronological order). The silent footage is shown between two lessons in “Instant Yiddish”: “When You Go To A Hotel” and “When You Are In Trouble”.

(Ken Jacobs, statement in “Films That Tell Time: A Ken Jacobs Retrospective”, American Museum of the Moving Image, 1989)

“Even before the first image of Urban Peasants appears we have had a six minute lesson in Diaspora history called “Situation Three: Getting A Hotel”. (The assumption is mind-blowing: Where in the world, with the possible exception of Birobidzhan, would one ever need to call room service in Yiddish ?) A second excerpt, “Situation Eight: When You Are in Trouble”, provides the film’s double edged punch line: “I am an American … Everything is all right.” Jacobs’s deceptively simple juxtaposition makes it impossible to watch the homely clowning of his wife’s wartime, half-Americanised family without picturing the “situation” of their European counterparts.”

(Jim Hoberman, excerpt from “Jacob’s Ladder”, Village Voice, 1989)

GLOBE

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1969, 16mm, colour, sound on cassette, 22 min

Formerly titled Excerpt from the Russian Revolution

First film, to our knowledge, designed to appear in deep 3D via the Pulfrich Effect, a single dark plastic filter interfering with and absorbing most of the light going to the eye it’s held in front of (both eyes remaining open). For this film, because all foreground motion is to the right, and because we want depth to appear as it would in life, the filter (perhaps conveniently taped to an eyebrow) is to be held before the right eye. Film was shot with a standard movie-camera and is to be projected with no special devices or requirements. Depth-phenomena does depend on onscreen lateral motion, left / right shifting of pictured elements relative to each other. As with audio stereo, middle seating is best; depth will expand with distance from the screen.

Locale is the upper-middle-class Stair Development newly built to provide housing for the executive class of IBM in Binghampton, on northern New York State’s “snow belt”. A beautiful, hilly, forested area of the globe, ripe for ‘development’, though at present spared due to economic decline due to manufacturing having been moved offshore. Please note the absence of sidewalks, of corner stores, of neighbourhood schools and therefore of a neighbourhood. We see a near-absence of people. Garages are connected to homes; residents do not step out, they drive out, in order to shop (anonymously) at a choice of malls, to go to work or to school or to meet with friends, etc. (kids are driven out to “play-dates” at other kids’ homes or are taken to and picked up from organised after-school programmes; they never simply gather after-school with neighbourhood chums). Such are the prize lives of the area, the IBM winners. We Americans tend to be the first humans among the world’s groupings to be so experimented on. If we seem to adapt, willingly jettisoning prior social arrangements, the new life-style is deemed ready for export. Look for a Stair Development coming your way! But do remember, when Cultural Imperialism is discussed, that, because the wave rolls over us first, and we are the first to be sold on giving up our ways, it should not be thought of as American Cultural Imperialism. It’s the world’s Corporate Future, with America as test-site.

Audio is side A of the LP “The Sensuous Woman”, circa 1969. It illustrates the near-instant co-opting and commodifying of The Sexual Revolution.

(Ken Jacobs, 2000)

Also Screening:

Thursday 2 November 2000, at 7:30pm, Brighton Cinematheque

Tuesday 7 November 2000, at 6:30pm, Glasgow Film Theatre

Thursday 30 November 2000, at 7:30pm, Hull Screen

Monday 4 December 2000, at 6:10pm, Manchester Cornerhouse

Wednesday 6 December 2000, at 9pm, London Lux Centre

Tuesday 12 December 2000, at 6:30pm, Sheffield Showroom

Back to top

Date: 19 October 2000 | Season: Leeds Film Festival 2000

APPARITIONS OF CLÉMENTI

Thursday 19 October 2000, at 6pm

Leeds City Art Gallery

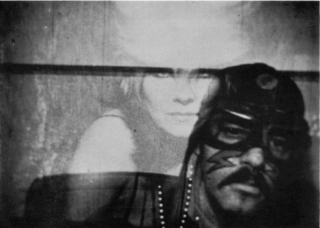

To honour the memory of the Pierre Clémenti, who died last year, a rare screening of his very personal experimental films. The flamboyant French actor is well-known to aficionados of European cinema, as he has appeared in important films by directors such as Visconti (The Leopard, 1963), Bunuel (The Milky Way, 1969), Bertolucci (The Conformist, 1970), and Jancso (The Pacifist, 1971). His acting ability may have been limited, but his sultry, bohemian good looks meant he regularly played small but significant parts, belatedly receiving his first major starring role in Benjamin (1967) by Michel Deville, opposite Catherine Deneuve (together again following Bunuel’s Belle de jour the previous year). Clémenti seemed to shy away from box-office success and favoured artistically challenging work, appearing in several early existential films by his friend Philippe Garrel, and such difficult works as Makavejev’s Sweet Movie (1974) and Pasolini’s Pigsty (1969).

In his own films, he pursues an intimate, poetic vision, weaving a complex tapestry of fact and fantasy. Influenced by the diary films of Jonas Mekas and Taylor Mead, and excited by screenings of the American underground, Clémenti created his own informal and psychedelic cinema style. Visa de censure n° X (1967-75) was named after the ‘visa de controle’, a document that must be issued for each film before public screenings in France, a country which at that time was over zealous in restricting works that were politically or socially undesirable. This air of extreme censorship meant that few French personal films were made in the late 1960’s, a period which saw the most experimental film activity in other countries. This first film is an eclectic mix of superimposition, neon light traces & time-lapse photography, combining real life footage with theatrical invention to capture an evocative memory of a free-wheeling era.

Always courting controversy and flaunting a disregard for authority, in the late 60s Clémenti was active in the radical Parisian youth movement and in 1971 was arrested in Italy on drugs charges. Following his incarceration he began to work on New Old (1979), a film and book which chronicled his activities as an actor and the everyday events surrounding the conception of his only fiction film A L’ombre de la canaille bleu (finally realised in 1987). Feeling he was at a point of no return, Clémenti embarked upon this stark confessional.

After his heydey, Clémenti continued to appear in numerous feature films. Some, like The Son Of Amr is Dead (Jean Jacques Adrien, 1978) were artistic and critical successes, but as his looks faded, he became less in demand and was forced to lower his standards, stumbling through rarely shown European productions as ill-health incapacitated his ability to perform. His last role was a minor part in Hideous Kinky (1998), a tale of enlightenment that must have been a sore reminder of his own spiritual journeys of the past. Clémenti died of cancer, aged 57, in December 1999.

Pierre Clémenti, Visa de censure n° X, France, 1967-75, 16mm, colour, sound, 42 min

Pierre Clémenti, New Old, France, 1978-79, 16mm, colour, sound, 64 min

This programme subsequently screened at London ICA Cinema and Brighton Cinematheque.

Back to top