Date: 3 November 2000 | Season: Ken Jacobs Nervous System

KEN JACOBS’ NERVOUS SYSTEM

London Film Festival Touring Programme

Friday 3 – Friday 10 November 2000

Distinguished filmmaker Ken Jacobs will present the British premiere performances of the Nervous System, an innovative live projection technique that he has been developing since the mid-1970s. These works will use two adapted 35mm filmstrip projectors containing identical sections of film. Jacobs manipulates the footage by hand, using a special propeller device to act as an adjustable shutter to vary the relationship between the image from each projector. The Nervous System creates a dynamic optical tug-of-war as the mind tries to resolve what IS there with what seems to be there. This is no impenetrable experimental film for the avant-garde elite, it is dazzling cine-magic to astound all ages.

Assisted by his wife Florence, Jacobs operates the Nervous System like a master musician, improvising wildly through intensely rehearsed visual riffs, refining an approach first hinted at in his influential early film wonder Tom, Tom The Piper’s Son (1969). Freeze frames, forward and reverse motion, inverse and mirrored images flicker through the projector as viewers find themselves giggling with disbelief as the screen appears to rotate while the brain tries to interpret what the eyes are seeing. In undermining the basic 24 frames per second principle of standard film practice, Jacobs creates frozen time. Expanding on Muybridge, Marey and the theories of early film, he unlocks the unknown possibilities hidden deep within cinema, the depth of composition that is usually lost in the unretarded flurry of frames. What may appear frozen or stationary, on the screen can imperceptibly develop motion or suddenly rush forward in an orgasm of movement. The thrill of motion overtakes the need for narrative. Rather than pursue lifelike illusion, Jacobs uses Pulfrich 3D and “Eternalism” to break down the image, creating fantastic relationships within the frames of standard, often archival, film, mining cinema to display its unrealised beauty.

For the London Film Festival, Jacobs will present two very different programmes consisting of films and Nervous System pieces, including :-

Bi-Temporal Vision: The Sea (1994), a performance to be viewed through Pulfrich filters. Jacobs re-interprets 15 seconds of footage of reflections on water, producing paradoxical perceptions of movement, the illusion of 3D going beyond any titillating monster movie trick. The unstable, abstract imagery shifts in unbelievable complexity. “The mind is soon at sea, Rorschaching like crazy in the effort to maintain equilibrium”. Jacobs exploits the act of perception to bring to the cinema screen the sophisticated formalism of abstract expressionist or cubist composition.

Ontic Antics with Laurel & Hardy (1998). Using footage from Stan and Ollie’s 1929 short film Berth Marks, Jacobs takes us beyond slapstick, defying time, space and gravity to provide an unimagined visual comedy.

KEN JACOBS’ NERVOUS SYSTEM TOUR

Friday 3 November 2000, London Film Festival

OPENING THE NINETEENTH CENTURY: 1896 (1990, 11 min) Pulfrich 3D 16mm film

BI-TEMPORAL VISION: THE SEA (1994, c.60-70 min) Pulfrich 3D Nervous System

Saturday 4 November 2000, London Film Festival

THE GEORGETOWN LOOP (1996, 11 min) widescreen 35mm film

ONTIC ANTICS STARRING LAUREL & HARDY (1998, 60 min) widescreen Nervous System

BERTH MARKS (1929, 18 min) the original Laurel & Hardy 16mm source film

DISORIENT EXPRESS (1996, 30 min) widescreen 35mm film

Sunday 5 November 2000, London Lux Centre

THE ALPS AND THE JEWS (1986-present, c.60-90 min) Pulfrich 3D dual slide / dual 16mm film (work-in-progress)

+ KIRK AND KERRY ( 1996, 25 min) film by Azazel Jacobs

Tuesday 7 November 2000, Oxford Phoenix Picture House

CRYSTAL PALACE (1997, 25 min) Nervous Magic Lantern

COUPLING (1996, 60 min) Nervous System

Thursday 9 November 2000, Manchester Cornerhouse

ONTIC ANTICS STARRING LAUREL & HARDY (1998, 60 min) widescreen Nervous System

BERTH MARKS (1929, 18 min) the original Laurel & Hardy 16mm source film

DISORIENT EXPRESS (1996, 30 min) widescreen 35mm film

Friday 10 November 2000, Nottingham Broadway Media Centre

CRYSTAL PALACE (1997, 25 min) Nervous Magic Lantern

DISORIENT EXPRESS (1996, 30 min) widescreen 35mm film

PHONOGRAPH (1990, 15 min) audiotape

SLOWSCAN (1981, 10 min) videotape by Ralph Hocking

JACOB’S LADDER (1981, 4 min) film by James Otis

UN PETIT TRAIN DE PLAISIR (1999, 30 min) Nervous System

Ken Jacobs’ Nervous System is a BFI Touring Programme funded by the Arts Council of England and supported by the 44th Regus London Film Festival. The season is curated by Mark Webber.

Thank you Sandra Hebron, Tricia Tuttle, Helen De Witt, Emma Heddich, Catharine Des Forges, Joanna Denham, Ben Cook, Ken and Florence Jacobs.

Date: 3 November 2000 | Season: Ken Jacobs Nervous System, London Film Festival 2000 | Tags: London Film Festival

KEN JACOBS’ NERVOUS SYSTEM: 1

44th Regus London Film Festival

Friday 3 November 2000, at 7:30pm

INSTRUCTIONS TO AUDIENCE

In order to appreciate the added depth of the Pulfrich 3D effect, the viewer should use the “Eye Opener” filter during both of the works presented in this programme. Please return the filter to cinema staff after the performance.

OPENING THE NINETEENTH CENTURY: 1896

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1990, Pulfrich 3D 16mm, colour, sound, 11 min

Shafting the screen: the projector beam maintains its angle as it meets the screen and keeps on going, introducing volume as well as light, just as in Paris, Cairo and Venice of a century ago happen to pass. Passing through the tunnel mid-film, a red flash will signal you to switch your single Pulfrich filter before your right eye to before your left (keep both eyes open). Centre seating is best: depth deepens viewing further from the screen. Handle filter by edges to preserve clarity. Either side of filter may face screen. Filter can be held at any angle, there’s no “up” or “down” side. Also, two filters before an eye does not work better than one, and a filter in front of each only negates the effects. (Ken Jacobs)

BITEMPORAL VISION: THE SEA

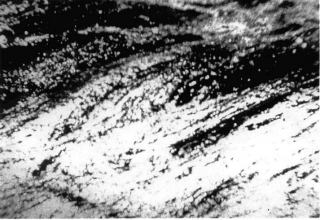

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1994, Pulfrich 3D Nervous System, b/w, sound, c.70 min

Nervous System riff on 587 frames photographed by filmmaker Phil Solomon. This work was inspired, during a visit to Hamburg, by the photography of Daniel Maier-Reimer. The surface of water becomes a hugely 3D cosmic cataclysm; what’s up, what’s down, forward or back or solid or open becomes entirely unstable. The mind is soon at sea, Rorschaching like crazy in the effort to maintain equilibrium. (Ken Jacobs)

Suggestions for use of the neutral density (Pulfrich) filter for Bitemporal Vision: The Sea :-

Only one filter to each viewer. Filter is held before one eye, both eyes remaining open. Viewer decides when to view the film through the filter, and which eye to place it in front of. Middle viewing positions are best (as with all stereo).

It takes time to appreciate the changes, and to familiarise with the process. Sail through any initial discomforts; the brain is a muscle that can be sluggish and grumpy when asked to learn new tricks.

The image is strongly 3D even without the filter but the filter will strongly enhance the depth. It can also radically change arrangement in depth. Choice of eye determines which parts of the scene are in front of or in back of other parts, and in which direction movement flows. The more abstract and non-representational the scene – releasing the mind from its knowledge of physical law and its expectations re. behaviour of objects in space – the more it is that changes can be seen; that is, acknowledged by the mind. So I suggest using the filter most intensively when this depiction of water is least recognisable as water. (Two straightforward camera takes are the basis of Bitemporal Vision: The Sea, but departure from the familiar will be unmistakable.) Try it, for instance, when the overall scene becomes lighter in tone following the first advancing wave. (A wave rumbling forward slightly below eye level…that will transform to a massive cloud form moving overhead …)

It may take a minute to adapt to the filter before seeing its effect. Hang in with it and more visual events will become apparent, all the drama and struggle and comings and goings of the details. Placing the filter left or right, to match the direction to which a form is moving, will advance that form towards the viewer. The filter can also convert a solid form into an open space, and (switch filter) vice-versa.

(Ken Jacobs)

FURTHER NOTES

THE PULFRICH EFFECT

The Pulfrich Effect. A dark grey filter is held before one eye, both eyes remaining open. The effect of the filter is a delay in the time it takes for the light that does pass through it to be signalled to the brain. One eye will now be seeing the image presently lighting up the screen while the other will be seeing the film frame flashed a moment ago. It becomes possible to offer the mind, simultaneously, two distinct but related views of a scene. Complete stereopsis becomes possible, convincing 3D, true-to-life or anything but according to how the two information bundles relate.

Each viewer of Bitemporal Vision: The Sea is offered a wand with truly magical properties. A filter on one end, it can be handled like a lorgnette. At the viewer’s discretion it can be placed when wanted either in front of the left or right eye, either enhancing the depth character of the scene or – especially in the more abstract passages – entirely transforming depth character. Shapes suddenly appear or disappear, or radically reshape. Figure and ground trade places; direction of movement changes.

But the viewer, of course, is not being asked to simply make note of the changes: They’re to be experienced, through intense and prolonged and empathetic observation.

The Nervous System consists, very basically, of two near identical prints on two stills capable of single frame advance and “freeze” (turning the movie back into a series of stills), frame … by … frame, in various degrees of synchronisation. Most often there’s only a single frame difference. Difference makes for movement and uncanny three dimensional space illusions via a shutting mask or spinning propeller up front, between the projectors, alternating the cast images. Tiny shifts in the way the two images overlap create radically different effects. The throbbing flickering is necessary to create “eternalisms”: unfrozen slices of time, sustained movements going nowhere unlike anything in life (at no time are loops employed).

I’ve said, “Advanced filmmaking leads to Muybridge”. That’s certainly true for me. Closing in on (to allow the expansion of) ever smaller pieces of time is my personal ever promising and inviting Black Hole. Actors’ faces can stun me with boredom. (Movies are about actors.) I confess I feel walled in by human faces altogether, not as misanthropic reaction but because the human colonisation of human experience, in our urban lives, is so thorough. It is astonishing to find oneself here with so many others to chat with, but isn’t this essentially a search party … with our work cut out for us? We’ve gotten caught in the makings of our own minds and the only way out seems to be to enter into the workings of the mind. Film – as itself the subject of inquiry – is the spell we enter so as to pull apart the fibres of this phantasm, our opportunity to lay out the mind in strips. So, if picking at the texture of cinema, at the end of its filmic phase, seems about as inward as one can get, it’s because the name of this digging tool I’ve devised, The Nervous System, also designates a main territory of its search, that place where we’ve blithely applied mechanism to mind, willy nilly producing that development of mind known as cinema. After all, the micro and macro worlds are equally “out there”. Fresh air rushes in from the core of things, too.

(Ken Jacobs)

Back to top

Date: 4 November 2000 | Season: Ken Jacobs Nervous System, London Film Festival 2000 | Tags: London Film Festival

KEN JACOBS’ NERVOUS SYSTEM: 2

44th Regus London Film Festival

Saturday 4 November 2000, at 1pm

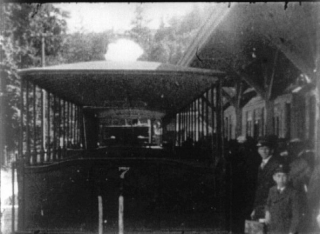

THE GEORGETOWN LOOP

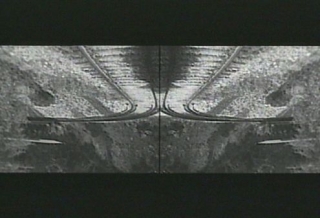

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1996, 35mm, b/w, silent, 11 min

Originally photographed in 1903, US Library of Congress collection. New arrangement in 1996 by Ken Jacobs, assisted by Florence Jacobs. 35mm optical rephotography by Sam Bush, Western Cine, Denver.

I’ve been raiding the Paper Print Collection of the Library Of Congress in Washington, DC, since the late 1960s with Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son. It’s a preserve of early cinema. Until 1912, in order to copyright film, one deposited with the library a positive from the negative printed on paper, unprojectable, but – unlike nitrate prints – capable of weathering the years without Crumbling into chemical volatility. And there the stacks rested, safely out of mind, hundreds and hundreds of silent rolls most less than 30 meters, many Edisons, American Mutoscope And Biograph, Gaumont, Lubin, Vitagraph …; cine-snatches of life as it was lived, vaudevillians, proto-dramas, and too many state parades. Until they were ripe for rediscovery and reevaluation, and rephotography back onto film. The Georgetown Loop is my 11-minute riff on “The Scenic Wonder of Colorado”, a rail-line built in the 1870s through daunting mountain terrain to serve the silver mining industry. I’ve called it the first landscape film deserving of an X-rating, and that it is, yet its secret subtitle is – I must whisper – (Celestial Railway). (Ken Jacobs)

“Elegantly reworking some 1906 footage of a train trip through the Colorado Rockies, the dean of radical filmmaking printed the original image and its mirror side by side to produce a stunning widescreen kaleidoscope effect. Did it really take 100 years of cinema for someone to execute this almost ridiculously simple idea ? “This landscape film deserves an X-rating”, says Jacobs.” (Jim Hoberman, Village Voice, 1996)

ONTIC ANTICS STARRING LAUREL AND HARDY

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1998, Nervous System, b/w, sound, c.60 min

“With his Nervous System film performances, Jacobs wrings changes out of startled frames and makes the infinitesimal matter. Ontic Antics with Laurel and Hardy – the simple shift of a vowel or the advance of a film frame creates a world of definition and character. Basking in that shade of difference he plumbs the frame with surgical decisiveness and amatory delicacy. Welcome to microtonal cinema. Taking Laurel and Hardy’s Berth Marks as point of departure, Jacobs supersedes slapstick, moving into the deeper dimensions of the human comedy. Psychological imbroglios, time-space predicaments, the unruliness of uncooperative gravity, the unlimited expressiveness of the limited body hallucinated into Rorschach-ing deliveries.” (Mark McElhatten)

Hardy walked a thin line between playing heavy and playing fatty. Laurel adopted a retarded squint, with suggestions of idiot savant. Their characters were at sea, clinging to each other as industrial capitalism was breaking up and sinking. Beautiful losers, they kept it funny, buoying our spirits. Laurel and Hardy … forever. (Ken Jacobs)

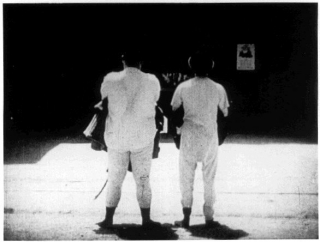

BERTH MARKS

Lewis R. Foster, USA, 1929, 16mm, b/w, sound, 18 min

Oliver Hardy goes to meet his partner Stan Laurel at the train station. They have a vaudeville act, which involves a bass fiddle, and are on their way to their next performance. They just barely make the train and are led to their berth, wreaking havoc amongst the other passengers in their wake. With much difficulty, they undress in their berth. As soon as they’re ready for bed, they arrive at Pottsville, their destination, and have to hurry off. Once the train has left the station, they discover that they have left their bass fiddle on board. But the situations aren’t important, it’s what the boys do with them – the way Ollie wanders around the station in search of Stan, just missing him several times, and the various contortions the pair try to get into their upper berth – that give the film its fun. Especially nice is the interchange between the boys and the conductor. When Ollie describes himself and Stan to the trainman as a “big-time vaudeville act”, the old man dryly replies, “Well, I bet you’re good !” (Janiss Garza, All Movie Guide)

DISORIENT EXPRESS

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1996, 35mm film, b/w, silent, 30 min

1906 – Original cinematographer unknown. 1996 – New arrangement by Ken Jacobs. Shots shown as found in “A Trip Down Mount Tamalpais”, the Paper Print Collection, Library of Congress. Optically copied by Sam Bush, Western Cine Lab., Denver, from l6mm to 35mm letterbox format to allow double-image mirroring in 1:85 ratio projection.

The same string of shots, in their entirety, is repeated in various placement and directional permutations. But this film is not a lately arrived example of ‘‘Structural Cinema”, where methods of ordering film materials often came to take on paramount value. (The viewer at some point grasped the method and that could be pretty much it.) I’m for order only to the extent it provides possibilities of fresh experience. For instance, kaleidoscopic symmetry in Disorient Express is not an end in itself. The radiant patterning that affirms the screen plane serves also to provide visual events of an entirely other magnitude. Flat transmutes repeatedly to massive depth illusion; yet that which appears so forcefully, convincingly in depth is patently unreal – an irrational space. The obvious filmic flips and turns (method is always evident) of the scenic trip provide perceptual challenges to our understanding of reality, and we are often unable to see things as we know they are.

With light-source shifted from heaven-sent to infernal, we see a landscape that could never be, except via cinema. A very early recording of a train trip through mountainous terrain, enthusiasm of the adventurous passengers on boisterous display, lends itself to us for a ride into each our own Rorschach wilderness. This careening trip also demands some hanging on, some output of viewer energy. The rightness of the closure (as I see it) was made possible by copying the film, for the last pass, in reverse motion.

Disorient Express takes you someplace else. A spin lasting 30 minutes, you really need to tap into your own reserves of energy. Hang on, please, this is not formalist cinema; order interests me only to the extent that it can provide experience. Watch the flat screen give way to some kind of 3D thrust, look for impossible depth inversions, for jewelled splendour, for CATscans of the brain. I’m banking on this film reviving a yen for expanded consciousness. (Ken Jacobs)

FURTHER NOTES

NOTES ON THE NERVOUS SYSTEM

The Nervous System consists, very basically, of two identical prints on two projectors capable of single-frame advance and “freeze” (turning the movie back into a series of closely related slides.) The twin prints plod through the projectors, frame … by … frame, in various degrees of synchronisation. Most often there’s only a single frame difference. Difference makes for movement, and uncanny three-dimensional space illusions via a shuttling mask or spinning propeller up front, between the projectors, alternating the cast images. Tiny shifts in the way the two images overlap create radically different effects. The throbbing flickering (which takes some getting used to, then becoming no more difficult than following a sunset through passing trees from a moving car) is necessary to create “eternalisms” – unfrozen slices of time, sustained movements going nowhere unlike anything in life (at no time are loops employed). For instance, without discernible start and stop and repeat points a neck may turn … eternally.

The aim is neither to achieve a life-like nor a Black Lagoon 3D illusionism, but to pull a tense plastic play of volume configurations and movements out of standard (2D) pictorial patterning. The space I mean to contract, however, is between now and then, that other present that dropped its shadow on film.

I enjoy mining existing film, seeing what film remembers, what’s missed when it clacks by at Normal Speed. Normal Speed is good ! It tells us stories and much more but it is inefficient in gleaning all possible information from the film-ribbon. And there’s already so much film. Let’s draw some of it out for a deep look, sometimes mix with it, take it further or at least into a new light with flexible expressive projection. We’re urban creatures, sadly, living in movies, i.e. forceful transmissions of other people’s ideas. To film our environment is to film film; it’s also a desperate approach to learning our own minds.

What I’m trying to do is shape a poetry of motion, time / motion studies touched and shifted with a concern for how things feel, to open fresh territory for sentient exploration, creating spectacle from dross … delving and learning beyond the intended message or cover-up, seeing how much history can be salvaged when film is wrested from glib 24 f.p.s. To tell a story in new ways, relating new energy components (words are energy components to a poet) in a system of construction natural to their particularity. To memorialise. To warn.

(Ken Jacobs)

Back to top

Date: 9 November 2000 | Season: Ken Jacobs Nervous System

KEN JACOBS’ NERVOUS SYSTEM

Manchester Cornerhouse

Thursday 9 November 2000, at 7:30pm

ONTIC ANTICS STARRING LAUREL AND HARDY

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1998, Nervous System, b/w, sound, c.60 min

“With his Nervous System film performances, Jacobs wrings changes out of startled frames and makes the infinitesimal matter. Ontic Antics with Laurel and Hardy – the simple shift of a vowel or the advance of a film frame creates a world of definition and character. Basking in that shade of difference he plumbs the frame with surgical decisiveness and amatory delicacy. Welcome to microtonal cinema. Taking Laurel and Hardy’s Berth Marks as point of departure, Jacobs supersedes slapstick, moving into the deeper dimensions of the human comedy. Psychological imbroglios, time-space predicaments, the unruliness of uncooperative gravity, the unlimited expressiveness of the limited body hallucinated into Rorschach-ing deliveries.” (Mark McElhatten)

Hardy walked a thin line between playing heavy and playing fatty. Laurel adopted a retarded squint, with suggestions of idiot savant. Their characters were at sea, clinging to each other as industrial capitalism was breaking up and sinking. Beautiful losers, they kept it funny, buoying our spirits. Laurel and Hardy … forever. (Ken Jacobs)

BERTH MARKS

Lewis R. Foster, USA, 1929, 16mm, b/w, sound, 18 min

Oliver Hardy goes to meet his partner Stan Laurel at the train station. They have a vaudeville act, which involves a bass fiddle, and are on their way to their next performance. They just barely make the train and are led to their berth, wreaking havoc amongst the other passengers in their wake. With much difficulty, they undress in their berth. As soon as they’re ready for bed, they arrive at Pottsville, their destination, and have to hurry off. Once the train has left the station, they discover that they have left their bass fiddle on board. But the situations aren’t important, it’s what the boys do with them – the way Ollie wanders around the station in search of Stan, just missing him several times, and the various contortions the pair try to get into their upper berth – that give the film its fun. Especially nice is the interchange between the boys and the conductor. When Ollie describes himself and Stan to the trainman as a “big-time vaudeville act”, the old man dryly replies, “Well, I bet you’re good !” (Janiss Garza, All Movie Guide)

DISORIENT EXPRESS

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1996, 35mm, b/w, silent, 30 min

1906 – Original cinematographer unknown. 1996 – New arrangement by Ken Jacobs. Shots shown as found in “A Trip Down Mount Tamalpais”, the Paper Print Collection, Library of Congress. Optically copied by Sam Bush, Western Cine Lab., Denver, from l6mm to 35mm letterbox format to allow double-image mirroring in 1:85 ratio projection.

The same string of shots, in their entirety, is repeated in various placement and directional permutations. But this film is not a lately arrived example of ‘‘Structural Cinema”, where methods of ordering film materials often came to take on paramount value. (The viewer at some point grasped the method and that could be pretty much it.) I’m for order only to the extent it provides possibilities of fresh experience. For instance, kaleidoscopic symmetry in Disorient Express is not an end in itself. The radiant patterning that affirms the screen plane serves also to provide visual events of an entirely other magnitude. Flat transmutes repeatedly to massive depth illusion; yet that which appears so forcefully, convincingly in depth is patently unreal – an irrational space. The obvious filmic flips and turns (method is always evident) of the scenic trip provide perceptual challenges to our understanding of reality, and we are often unable to see things as we know they are.

With light-source shifted from heaven-sent to infernal, we see a landscape that could never be, except via cinema. A very early recording of a train trip through mountainous terrain, enthusiasm of the adventurous passengers on boisterous display, lends itself to us for a ride into each our own Rorschach wilderness. This careening trip also demands some hanging on, some output of viewer energy. The rightness of the closure (as I see it) was made possible by copying the film, for the last pass, in reverse motion.

Disorient Express takes you someplace else. A spin lasting 30 minutes, you really need to tap into your own reserves of energy. Hang on, please, this is not formalist cinema; order interests me only to the extent that it can provide experience. Watch the flat screen give way to some kind of 3D thrust, look for impossible depth inversions, for jewelled splendour, for CATscans of the brain. I’m banking on this film reviving a yen for expanded consciousness. (Ken Jacobs)

FURTHER NOTES

NOTES ON THE NERVOUS SYSTEM

The Nervous System consists, very basically, of two identical prints on two projectors capable of single-frame advance and “freeze” (turning the movie back into a series of closely related slides.) The twin prints plod through the projectors, frame … by … frame, in various degrees of synchronisation. Most often there’s only a single frame difference. Difference makes for movement, and uncanny three-dimensional space illusions via a shuttling mask or spinning propeller up front, between the projectors, alternating the cast images. Tiny shifts in the way the two images overlap create radically different effects. The throbbing flickering (which takes some getting used to, then becoming no more difficult than following a sunset through passing trees from a moving car) is necessary to create “eternalisms” – unfrozen slices of time, sustained movements going nowhere unlike anything in life (at no time are loops employed). For instance, without discernible start and stop and repeat points a neck may turn … eternally.

The aim is neither to achieve a life-like nor a Black Lagoon 3D illusionism, but to pull a tense plastic play of volume configurations and movements out of standard (2D) pictorial patterning. The space I mean to contract, however, is between now and then, that other present that dropped its shadow on film.

I enjoy mining existing film, seeing what film remembers, what’s missed when it clacks by at Normal Speed. Normal Speed is good ! It tells us stories and much more but it is inefficient in gleaning all possible information from the film-ribbon. And there’s already so much film. Let’s draw some of it out for a deep look, sometimes mix with it, take it further or at least into a new light with flexible expressive projection. We’re urban creatures, sadly, living in movies, i.e. forceful transmissions of other people’s ideas. To film our environment is to film film; it’s also a desperate approach to learning our own minds.

What I’m trying to do is shape a poetry of motion, time / motion studies touched and shifted with a concern for how things feel, to open fresh territory for sentient exploration, creating spectacle from dross … delving and learning beyond the intended message or cover-up, seeing how much history can be salvaged when film is wrested from glib 24 f.p.s. To tell a story in new ways, relating new energy components (words are energy components to a poet) in a system of construction natural to their particularity. To memorialise. To warn.

(Ken Jacobs)

Back to top

Date: 10 November 2000 | Season: Ken Jacobs Nervous System

KEN JACOBS’ NERVOUS SYSTEM

Nottingham Broadway Media Centre

Friday 10 November 2000, at 7pm

CRYSTAL PALACE

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1997, Nervous Magic Lantern, b/w, sound, c.25 min

Impossible movements … impossible spaces … issue forth from a single, somewhat unusual slide projector (of British manufacture) employed in an unexpected way. Cinema without film or electronics. And, as with The Nervous System (utilising pairs of projectors), depth phenomena is produced that can be seen as such without special viewing spectacles, and even by a single eye. (Ken Jacobs)

DISORIENT EXPRESS

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1996, 35mm, b/w, silent, 30 min

1906 – Original cinematographer unknown. 1996 – New arrangement by Ken Jacobs. Shots shown as found in “A Trip Down Mount Tamalpais”, the Paper Print Collection, Library of Congress. Optically copied by Sam Bush, Western Cine Lab., Denver, from 16mm to 35mm letterbox format to allow double-image mirroring in 1:85 ratio projection.

The same string of shots, in their entirety, is repeated in various placement and directional permutations. But this film is not a lately arrived example of ‘‘Structural Cinema”, where methods of ordering film materials often came to take on paramount value. (The viewer at some point grasped the method and that could be pretty much it.) I’m for order only to the extent it provides possibilities of fresh experience. For instance, kaleidoscopic symmetry in Disorient Express is not an end in itself. The radiant patterning that affirms the screen plane serves also to provide visual events of an entirely other magnitude. Flat transmutes repeatedly to massive depth illusion; yet that which appears so forcefully, convincingly in depth is patently unreal – an irrational space. The obvious filmic flips and turns (method is always evident) of the scenic trip provide perceptual challenges to our understanding of reality, and we are often unable to see things as we know they are.

With light-source shifted from heaven-sent to infernal, we see a landscape that could never be, except via cinema. A very early recording of a train trip through mountainous terrain, enthusiasm of the adventurous passengers on boisterous display, lends itself to us for a ride into each our own Rorschach wilderness. This careening trip also demands some hanging on, some output of viewer energy. The rightness of the closure (as I see it) was made possible by copying the film, for the last pass, in reverse motion.

Disorient Express takes you someplace else. A spin lasting 30 minutes, you really need to tap into your own reserves of energy. Hang on, please, this is not formalist cinema; order interests me only to the extent that it can provide experience. Watch the flat screen give way to some kind of 3D thrust, look for impossible depth inversions, for jewelled splendour, for CATscans of the brain. I’m banking on this film reviving a yen for expanded consciousness. (Ken Jacobs)

PHONOGRAPH

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1990, audiotape, 15 min

One-take unedited audiotape. 15 minutes of loud black surround sound. (Ken Jacobs)

“Most ferocious sound I’ve ever heard”. (John Zorn)

SLOWSCAN

Ralph Hocking, USA, 1981, videotape, b/w, silent, 4 min (excerpt)

This is an ingenuous and astonishing work made by s happily reclusive artist who has created many marvels in photography and video, often featuring his wife Sherry (often undressed), but who makes no effort to exhibit. A champion of the possibilities of “low res” video, he remains free of addiction to the technically latest and the most. For me, his brusque and unfussy video art remains the latest and the most. It’s an honour to present even this small example. (Ken Jacobs)

JACOB’S LADDER

James Otis, USA, 16mm, b/w, silent, 4 min

Jacob’s Ladder is a black and white spiralling, swirling computer-generated abstract animation. It combines its technological origin and its imagery (reminiscent of natural processes and objects – fractals, polyps, branching plants, crystal growth) seamlessly and beautifully.” (Patrick Friel)

UN PETIT TRAIN DE PLAISIR

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1999, Nervous System, b/w, sound, c.25 min

25 minutes to traverse, by train, (perpendicular view of) a single open Paris street. Remember the smooth rubber “spaldeen” (Spaulding), high bouncer that – sometimes in a stickball game on the once streets of Brooklyn – would split evenly along its circling seam? And then as pink twin hemispheres made possible further fun. What had been the secret interior was revealed to be so much cleaner and fleshy smooth than the exterior. Suggestively libidinal before one knew what was what. There was no point attempting to fling a half-ball; irresistible was the impulse to invert it ! Pop, inside out. The optical implausibilities of Un Petit Train de Plaisir inverts mentalities like pink half-spaldeens. (Ken Jacobs)

This performance was made possible by the generosity and co-operation of Frank Abbott and Nottingham Trent University. Thanks also Caroline Hennigan and Laraine Porter at the Broadway.

FURTHER NOTES

KEN JACOBS’ NERVOUS SYSTEM, WHAT, WHY AND WHEREFORE

The Nervous System places two identical film prints on two projectors capable of single frame advance and freeze. The twin prints step through the projectors frame by frame as dictated by the artist-projectionist, caught somewhere between movie and slideshow. They tend to advance slightly out of synchronisation, usually with only a single frame difference. Difference makes for movement and uncanny three dimensional space-illusions when a spinning propeller up front, between the two projectors, interrupts and alternates their cast images. Tiny shifts in the way the two images overlap onscreen create radically different visual effects. The throbbing flicker (avoid viewing if you have a history of epilepsy) is necessary to the creation of “eternalisms”, unfrozen slices of time, sustained movements going nowheres unlike anything in life. For instance, without discernible start and stop and repeat points, a neck may turn … eternally.

I enjoy mining existing film, seeing more of what film remembers, what’s missed when it clicks by at Normal Speed. Normal Speed is good! It tells us stories and much more but it is inefficient at gleaning more than the surface from the film-ribbon. And there’s already so much film. Let’s draw some of it out for a deeper look, toy with it, take it into a new light with inventive and expressive projection. Freud would suggest doing so as a way to look into our minds. We’re urban creatures, after all, huddled for warmth against the great outside, living in movies. We lie down on the couch and remember movies.

Illusion is what we recognise when we face facts, when we acknowledge the gullibility of our senses. Stage-tricks help reconcile us to our carrot-on-a-stick relationship to truth; the amusing illusion, seen as such, warns against delusion. A dose of formulated craziness can be refreshingly therapeutic! (see Hellzapoppin’, 1941). For instance: 21/2 D is hard to conceive. Things should either be flat or in depth. Yet the lit rectangle doubly cast by The Nervous System presents us with an impossible mix of the flat – our usual reading of forms reshaping as they slide across the screen, one with the screen, and the deep – here the screen punctured by the point formed by our twin sight lines, blown open, fragmented, its surface seemingly divided among myriad objects reaching forward and back of the actual screen-plane, and something in between, with both flat and deep claiming appearances unto their respective realms. Things get twisted, caught in this optical tug-of-war. It’s The Nervous System ! Putting the tangle into rectangle, and leaving it a wreck.

Not only things pictured but the rectangle itself gets caught in the struggle and becomes spatially unstable, advancing or sinking in depth, stretching or compacting, leaning tilting swinging rising falling splitting, peeling off the screen The rectangle, itself in motion, becomes a creature of time.

“Time / motion study” hardly suggests the exercise in ecstasy this can be. Or that we’re touching on the essence of cinema, its original impetus: vivisection of the moment. After a century of cinema industrialised, standardised, economically determined and “rationalised”, we need a return to the possibilities of a Cubist cinema (Cubism would’ve been unthinkable without the revelations of pioneering cinema). Opening fresh territory for sentient exploration, bringing spectacle forth from dross. Delving beyond the usual movie-message / cover-up to see the history that can be salvaged when film is wrested from glib 24fps.

Toying with light, with phantasm, can also open time to fantastic changes. Temporal illusions of another order from the expansions/contractions of Griffith and Eisenstein – too emotionally congenial to register as modernist derangement and delirium, trigger the transcendent (rather than escapist) function of art. Explain a time, for instance, in which things race forward, with bursting velocity, and yet don’t for a moment budge … without the projectionist-performer’s permission. Time arrested in the act, while remaining time, i.e. with things remaining in motion. Wheels turning forward may even travel backwards (impossible to imagine) at the whim of the cine-puppeteer.

Well, what moves the puppeteer? The very specific possibilities inherent to a particular strand of film. This frame times that frame equals… it’s anyone’s guess until discovery of the exact formula of projection adjustments makes it plain, allows it to happen, and often it’s an effect unique to that coupling; no two other pictures will do. Control, then, is a matter of attending very closely to what’s on the film. One tries this and that, but the givens of the shot, and their impact on the performer-projectionist, swing the action.

Closing in on (to allow the expansion of) ever smaller pieces of time is my inviting Black Hole. Actor’s faces can stun me with boredom (movies are about actors.) I confess to feeling walled in by human faces altogether, not as misanthropic reaction but because the human colonisation of human experience, in our urban lives, is so thorough. It is astonishing to find oneself here with so many others to chat with, but isn’t this essentially a search party with our work cut out for us? We’ve gotten caught in the makings of our own minds and the only way out may be to enter into the workings of the mind. Film as itself the subject of film is the spell we enter wide-eyed, so as to get a grip on and pull apart the fibres of the phantasm. Film study is our opportunity to lay out the mind in strips. So – big breath – if picking at the texture of cinema at the end of its filmic phase (reality retreating further as our cine-solipsism goes electronic) seems about as inward as one can get, it’s because the name of this digging tool I’ve devised, The Nervous System, also designates a main territory of its search, that place where we’ve blithely applied mechanism to mind willy nilly producing that development of mind known as cinema. Micro and macro worlds are equally “out there”. Divide (the moment) and conquer; advanced filmmaking leads to Muybridge and Marey.

(Ken Jacobs)

Back to top

Date: 14 March 2001 | Season: Burroughs in Britain, Miscellaneous

GENIUS AND JUNKIE: BURROUGHS IN BRITAIN

Wednesday 14 March 2001, at 6:30pm

London Tate Britain Clore Auditorium

Cult author Iain Sinclair, film curator Mark Webber and Tim Marlow (BBC broadcaster and editor of tate: the art magazine) come together to revel in and debate the impact of the great American Beat novelist William Burroughs on the underground arts scene in London.

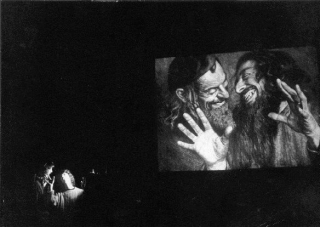

Focusing on the 1960s and 1970s, when Burroughs lived for a number of years in the city, this exciting event will include screenings of two films Burroughs made in collaboration with the British film-maker Antony Balch, The Cut-Ups (1963) and Towers Open Fire (1967).

Antony Balch, Towers Open Fire, 1963, 16mm, b/w, sound, 10 min

Antony Balch, The Cut-Ups, 1967, 16mm, b/w, sound, 19 min

PROGRAMME NOTES

Lock them out and block the door

Bar them out for evermore

Lock is mine and door is mine

Three times three to make up nine

Curse go back curse go back

Back with double pain and lack

Change the lock and change the door

Smear them out for evermore

Curse go back curse go back

Back with double fear and flack

Silver arrow through the night

Silver arrow take thy flight

Silver arrow seek and find

Cursing hearts and cursing minds

WHO WAS ANTONY BALCH ?

(some things about his film collaborations with William Burroughs & other tenuous connections leading further out)

I discovered the film collaborations of William Burroughs and Antony Balch as a teenager. They were an inevitable step for an inquisitive youth learning about the underground sub-culture. Back then, they were intriguing for their weirdness, but looking again at the films now, with my current understanding of the avant-garde, I am amazed by the formal innovation contained in the films. So many demonstrations of the power of cinema are harnessed in the brief 10 minutes of Towers Open Fire. Different sections echo developments in many areas of film practise. It’s hard to know how much of it was achieved consciously, since it is known that Balch and Burroughs had some limited exposure to experimental film. I have the impression that their collaborations existed almost in a vacuum, that the creativity was spontaneous and original, arising from the hotbed of invention they were working in. The ideas in the films have been so often imitated and diluted that people have forgotten the dynamism of their origin. Once produced, the films continued to exist outside of the recognised canon of experimental film, and aside from several screenings organised by the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative, were rarely seen alongside those of their peers. Balch’s grounding in more conventional cinematic business may be a reason for this, leading to the films being most often screened supporting feature films in first run or repertory theatres. We can only imagine the havoc they might reap on unsuspecting, upright members of a less sophisticated audience. It is a testimony to the strength of vision that even within the most avant-garde circles, The Cut-Ups still manages to provoke strong reactions.

The Cut-Up

Brion Gysin devised the cut-up process in the “Beat Hotel” at 9, rue Git-le-Coeur in September 1959. It was discovered by accident when he noticed the shredded columns of newsprint that he’d been using as support while he cut a mount for a drawing. Its main precedent in literary history was a piece by Tristan Tzara, a Romanian-born French author and leading Dada activist. He provoked a riot in the 1920s when he proposed to create a poem by pulling words at random out of a hat, prompting Andre Breton to expel him from the Surrealist group. Early examples of the application of the cut-up technique can be found in books by Gysin, Burroughs, Gregory Corso and Sinclair Beiles (a South African Jewish Poet of questionable mental stability, whose books include “Universal Truths as Revealed in White Tobacco Fumes”, “Sacred Fix” and the Olympia Press erotic novel “Houses of Joy” (using the exotic nom de plume of Wu Wu Meng)). These four authors collaborated on “Minutes To Go” (Two Cities Editions, 1960) and Burroughs and Gysin worked together again on “The Exterminator” (Auerhahn Press, 1960).

In his own work, Burroughs’ application of the cut-up was less literal and more literary, using it to formulate ideas that were then reworked and more consciously structured. His most evident use of the technique is in the three books “The Soft Machine” (Olympia Press, 1961), “The Ticket That Exploded” (Olympia Press, 1962) and “Nova Express” (Grove Press, 1964).

Tape Experimentation

During this time their colleague Ian Sommerville, an English mathematician, realised early tape compositions by similar means. Gysin and Sommerville’s early tape experiments received a public airing in England in 1960. “The Permutated Poems of Brion Gysin” (as put through a computer by Ian Sommerville), produced by Douglas Cleverdon at the Radiophonic Workshop and broadcast by the BBC. Combining layers and repeats of acoustically similar sounds, compositions like “Pistol Poem” bear similarities to the experiments done in the USA at the San Francisco Tape Music Centre, which was founded by Ramon Sender, Morton Subotnick and Terry Riley in 1959.

Tape music was first developed in post-war France by Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry on “Symphonie Pour Un Homme Seul” in 1950. The Columbia University tape studios were established a year later by Vladimir Ussachevsky and Otto Luening. These early laboratories laid the foundations for Musique Concrete, a new compositional form, which combined musical instruments with field recordings, electronically produced effects, and speech. The recordings by Gysin and Sommerville take a slightly different approach, being almost non- or anti- musical, impulsive and home made, more in-line with work of this period by John Cage and Richard Maxfield (who is known to have assembled audio at random, pulling cut-up sections of tape out of a bowl). Their influence on the new music pioneers is unclear, though from descriptions, the “Permeated Poems” and other early concrete or sound poetry appear closely related to later, better-known linguistic process music of Steve Reich (“It’s Gonna Rain, 1965, which developed out of a tape composition he’d made for Robert Nelson’s film Plastic Haircut in 1963) and Alvin Lucier (“I Am Sitting In A Room”, 1971). There are also parallels with the Concrete Poetry movement. In 1960, Gysin had founded the Domaine Poetique group with Henri Chopin, Françoise Dufrêne and Bernard Heidsieck. Taking sound poetry further into performance, the collective presented live events at the London ICA and Paris American Centre, combining sound with optic and perceptual experimentation such as projection of bodies onto bodies to transmit unsettling double visions.

Burroughs himself went on to investigate the magical properties of audiotape in the electronic “spells” he cast in the 60s and 70s. By playing recorded sound back to its source or at it’s original location he sought to create a kind of subliminal feedback loop. Its harmless analogy in music could be composer Max Neuhaus, who investigated environmental sound in pieces like “Public Supply” (1966), a work in which the sounds submitted by listeners over the telephone were instantly altered, combined and played back to them over the radio. Burroughs application of the technique was less benign; one story tells of Parisian newspaper kiosk that burnt down (with its malevolent owner inside) in ’61 or ’62 after one of his hostile street playbacks.

Antony Balch

Antony Balch was an Englishman who had been working in the film industry in London and Paris from an early age. Much of his childhood was spent at the movies, where his hero was Bela Lugosi. In the late 1950s, Balch made early television commercials, before working on English subtitles for foreign features distributed by Mondial Films, including films by Antonioni, Louis Malle and others. His first assignment was a British trailer for Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria (1957), and from there he progressed to being responsible for subtitling on Last Year at Marienbad (Alain Resnais, 1961), Dreams (Ingmar Bergman, 1955) and The Trial of Joan of Arc (Robert Bresson, 1962).

In 1959, Balch had begun a personal film project featuring his friend Jean-Claude de Feugas. After shooting around Paris with his wartime De Vry 35mmm camera, Balch realised it was “terribly pretentious” and abandoned the film. De Feugas lived at 10 rue Git-le-Coeur, and at a party in his apartment he introduced Balch to his neighbour Brion Gysin. Gysin subsequently introduced Burroughs to Balch, who became intrigued with the unusually creative group. Balch recognised the cinematic potential of the cut-up, and soon started to adapt and apply this technique in a series of film collaborations.

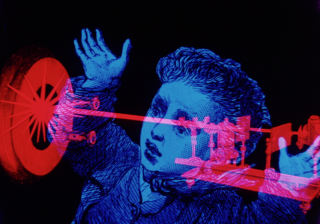

Towers Open Fire

Their first collaborative film was made on black and white 35mm in 1963. It was conceived by Balch and Burroughs with additional appearances from Ian Sommerville, Brion Gysin and Mikey Portman. Portman was an unpredictable and crude character Burroughs met and became infatuated with in October 1960. A 17 year old homosexual, drug addict and alcoholic, he was widely regarded as a liability, and no doubt an embarrassment to his family. His grandfather was the London real estate tycoon Lord Goodman, head of the Arts Council and private lawyer of Harold Wilson.

Towers Open Fire was devised as a cinematic realisation of Burroughs’ concepts such as the breakdown in control. The film contains rapid editing, flicker and strobe cuts, particularly in one innovative section, with Burroughs on the quayside, which consists of short cut-up sections, interrupting the natural flow of events. For this sequence, Balch had previously degraded the image quality by duping the print. The towers of the titles are a reference to ominous structures seen by Burroughs on the stretch of land between Gibraltar and Spain.

An improbable mixture of characters appear in the boardroom scene, which was shot in the BFI headquarters :-

- David Jacobs – host of the popular tv programme Juke Box Jury

- Bachoo Sen – producer / screenwriter of exploitation films including Love is a Splendid Illusion (Tom Clegg, 1970)

- Alexander Trocchi – Scottish writer whose novel novel “Cain’s Book” (1960) was based on his experiences as a heroin addict in New York. As with Burroughs’ “Junky” (Ace, 1953, as William Lee), the book originally appeared under a pseudonym. Trocchi was later one of the key organisers of the gathering of beat poets at the Royal Albert Hall in London, 1965. In the early days of the Olympia Press he wrote a ‘dirty book’ under the improbable pen name Carmencita de las Lunas

- Liam O’Leary – director of Our Country (1943) and Portrait of Dublin (1952), two important Irish documentary films, and acquisitions officer at the National Film Archive in London in the early 1960s. Author of “Invitation to the Film” (1945) and “Rex Ingram – Master of the Silent Film” (1980) and founder of Irish Film Archive

- Norman Warren – probably Norman J. Warren, director of exploitation films Satan’s Slave (1974) and Terror (1979)

- John Gillett – a respected freelance film critic

The film’s soundtrack opens with a section from the book “The Soft Machine”. Burroughs later reworked sections of the dialogue in the “Towers Open Fire” section of “Nova Express”. The BBFC requested removal of the words “fuck” and “shit” from the soundtrack but passed (or failed to notice) the shots of Balch masturbating, and of Burroughs shooting up. On each print, Balch hand painted, in colour, a short section of white leader at the end of film (during the Mikey Portman dance sequence). It’s a brief joyful distraction from the intense film, with shades of Len Lye. This section contains an impeccable mix of music, sound and silence. Balch later commented that he thought the film successful but hampered by his naïveté in being new to the radical concepts of the Burroughs group.

The film also contains footage of the prototype Dreamachine shot at “The Object” exhibition at the Musee des Arts Decoratifs in Paris, 1962. The Dreamachine was conceived by Gysin and built by Sommerville. It is a card cylinder with precisely cut holes. Mounted on a turntable and surrounding a light bulb, it was designed to be viewed with closed eyes. The stroboscopic effects were believed to stimulate the brain’s alpha waves, giving rise to visual hallucinations and mental stimulation.

The Cut-Ups

Between 1961-65, Balch shot Guerilla Conditions (aka Ghosts at #9, after the address of their Paris base) on 16mm. It was originally conceived as a 23-minute silent film documenting the daily lives of Burroughs and Gysin in Paris, Tangiers, London and New York. 23 is regarded as “the synchronicity number”, Burroughs believed (as do many others) that it has magical properties, claiming it naturally occurs more frequently than any other number. This film was not completed as planned and some of the hours of footage was subsequently included in The Cut-Ups. Balch edited together four separate reels of coherent material, which would be used as the film’s image bank. After determining an optimum length of shot that would enable an average viewer to recognise imagery without being able to interpret it, he instructed a lab technician to “take a foot from each roll and join them up”, performing the “mechanical process” of editing by sequentially assembling one-foot long sections from each reel. This pre-meditated mathematical and calculatedly precise editing arrangement (1, 2, 3, 4, 1, 2, 3, 4, etc.) make this an early (and unrecognised) Structural Film.

The soundtrack was a well orchestrated, persistent text assembled by Ian Sommervillle with Burroughs and Gysin reading a routine based on a Scientology training test. Though it is closely related to Gysin’s poetry and tape experiments, it uses vocal repetitions and permutations, but it is not a tape composition. The chosen texts appear to have been read “live”, and well timed to end with the film.

The controversial religio-scientific Scientology movement was developed in the 1950s by author L. Ron Hubbard. It derived from Dianetics, a form of psychotherapy that taught that every experience is recorded in the mind as a mental image. Their treatment of “engrams” (prior painful experiences stored in the subconscious mind) involved the use of tape recorders operated by an “auditor”. It is easy to see, from his beliefs and writings, why this subject should interest Burroughs, who was introduced to the movement by Brion Gysin in 1959.

The film originally had a running time of 20 minutes and 4 seconds. Balch, who was continuing his experiments with the rate of audience perception and reaction, showed it at both at 16 and 24fps during its premiere run in 1967. It seems hard to believe now, but the film opened with a two-week engagement at the Cinephone in Oxford Street, a regular movie house in the centre of London’s West End. During the course of this run Balch cut it down to a preferred 12 minute version. This cut may no longer exist, though I have vague memories of seeing it some years ago (and finding it more satisfying than the longer version). The version currently available on video and 16mm is the original. Genesis P’Orridge has reported of a 90 minute edit that Bryon Gysin claims was used at events by Domaine Poetique.

That Which is (or is Not) Structural

The Cut-Ups can be considered as part of a canon of films I regard as Pre-, Ex-, or Peri- Structural Films (I haven’t decided on the correct term yet, ideas are still being formulated…), which either predate or were made outside the accepted grouping constantly referenced in avant-garde film histories. My consideration of this grouping takes in works such as Zen For Film (Nam June Paik, 1962-64) which were outlined in George Maciunas’ answer to P. Adams Sitney’s original essay, the early films of Victor Grauer, The Maltese Cross Movement by Keewatin Dewdney (1967) and stretches further back into early cinema.

Though many lay this charge, Sitney never claimed to be all-inclusive. In his essay “Structural Film”, which was first published in Film Culture No. 47 (Summer 1969), he outlines a series of developments and ideas that he begin to formulate at the Knokke-Le-Zoute “Exprmntl 4” festival and competition in December 1967. His theories, which were subsequently re-thought and refined before a definitive publication in his book “Visionary Film” (Oxford University Press, 1974), were mostly concerned with work made since 1965. The essay was so timely and powerful that it was seized upon, almost as a manifesto, being often misinterpreted. The debate over it continues today, as does its influence. From the time of its publication, it directly, indirectly or inadvertently influenced the most significant tendency in avant-garde film, which continued through the 1970s, being that which is loosely concerned with investigating and displaying the properties and possibilities of the filmic material itself. The Cut-Ups appears to contain attributes that would bring it within Sitney’s interpretation, though it has unfortunately been ignored by those figures who internationally defined and represented the highest achievements of experimental (artistic) cinema.

Bill and Tony

A third film, Bill and Tony (aka Who’s Who) was made in either 1970 or 1972 on colour 35mm, though it was not submitted to the BBFC (and presumably not screened) until 1974. The film presents a kind of parlour game inspired by the routines of Brion Gysin and Ian Sommerville, performances by the Domaine Poetique group, and a Burroughs text called “John and Joe”. Burroughs and Balch are seen from the neck upwards, alternately reading excerpts from a Scientology manual and the script of Freaks. The speech of one is dubbed onto the head of the other, so they appear to speak with each-others voice. Brion Gysin has commented that the film was made to be subjected to a further transferral, being subsequently projected onto each-others head. In a Rolling Stone interview in 1972, Burroughs spoke of additional experiments with video using the Bill and Tony film projected onto their heads, and also of an experiment in which shots of their heads were alternated every frame (24 times per second).

The Naked Lunch Movie

All of these collective film experiments were seen as practise and research for the plan to realise a feature length interpretation of Burroughs’ celebrated novel “The Naked Lunch” (first published by Olympia in 1959). John Huston had earlier remarked that it would make a great film, but did not pursue that thought. Sometime around 1964, Brion Gysin wrote a screenplay and Antony Balch drew detailed storyboards, which went unrealised. This document was later rescued from Balch’s office (along with the other film materials) by Genesis P’Orridge in 1980.

In May 1971, Balch, Gysin and Burroughs co-founded Friendly Films Inc. specifically to produce the “Naked Lunch” film, which by this time featured six musical numbers by jazz saxophonist Steve Lacy, whose own musical output had turned towards the avant-garde in the mid-60s. (Lacy and Gysin later realised an album together on the Hat Art label in 1985.) That same year, it was widely reported that Mick Jagger may be taking the lead role, though it since came to light that he felt Balch was more interested in his sexual potential than his acting abilities. Also in this period of activity, the television producer Chuck Barris improbably had a brief flirtation with the project.

Barris was best known as the man responsible for such light entertainment fodder as The Newlywed Game and The Gong Show, and its not surprising he didn’t indulge Burroughs for long. Terry Southern, a friend of Burroughs and author of the succes de scandale Candy (GP Putnam, 1958), was also connected with the planned film at this time. Later, in 1977, financier Jacques Stern hired Southern to write a screenplay of Burroughs’ “Junky”, which he proposed would star Dennis Hopper (during one of his wayward periods). By hiring people with two of the most unreliable reputations in Hollywood, Stern ensured this project also went nowhere fast, though not before several thousand dollars had been spent in development.

Whilst plans for the “Naked Lunch” film were being developed, Balch sought to gain experience by directing two exploitation features. The Secrets of Sex (1970, aka Bizarre, Tales of the Bizarre or Eros Exploding) and Horror Hospital (1973, aka Computer Killers). Both films were produced by Richard Gordon, a small time exploitation huckster whose other titles include Devil Doll (Lindsay Shonteff, 1964), Tower of Evil (James P. O’Connolly, 1972) and The Cat and The Canary (Radley Metzger, 1978), and severely lack the visionary aspects of the earlier short films. They are bizarre in their mundanity, consisting of stiff and unimaginative acting, dialogue and camerawork. Secrets of Sex, which contains some vague allusions to Burroughs, Scientology and “Nova Express”, required 9 minutes of cuts by BBFC. Balch always contested that the film suffered greatly at the hands of the censor.

Freaks

During one sojourn in Paris, Balch had seen Tod Browning’s 1932 feature Freaks and via Kenneth Anger found that the rights holder was Raymond Rohauer. Rohauer was by many accounts an unscrupulous Californian film collector and distributor, who specialised in the early silents and exploited loopholes in copyright laws. Stan Brakhage worked for him in the late 1950s, and gave his first public lecture on film at his Coronet Theater in Los Angeles. Rohauer started the Hollywood Film Society, allegedly being the first to invite filmmakers and stars to attend and speak at retrospective screenings. As a result of one event, Rohauer was given an entire Buster Keaton archive, containing materials of every film he had ever appeared in. The films had been left in a garage when James Mason bought a house from Keaton. This donation led to the formation of Buster Keaton Productions, which transferred the nitrates, masters and negatives for re-releases. Rohauer went on to amass a collection of 3000 titles, which is now distributed by The Douris Corporation of Columbus, Ohio.

Balch bought a print of Freaks from Rohauer and became a distributor. It was awarded an “X” certificate in May 1963. The film, which featured real life human oddities, had a reputation of revulsion and had previously been rejected a certificate by the BBFC on 1 July 1932 (submitted by MGM), and again on 12 March 1952 (submitted by Adelphi Films Ltd). Balch’s new print opened at London’s Paris Theatre with Towers Open Fire and Vivre Sa Vie by Jean-Luc Godard (1962). What would today be seen as politically incorrect, or might possibly be acceptable and celebrated in light of recent Dogme 95 films, was then generally regarded as a dirty little film about things best left alone. Balch’s promotion of the film, much maligned since its conception, was an initial step in its becoming recognised as an important work in the development of horror and auteur filmmaking.

Balch Films Ltd.

Balch continued to buy the UK distribution rights for foreign productions, often renaming them in his individual style and occasionally performing radical re-editing. It was suggested that if he had been the distributor of Flaherty’s Nanook of the North, he would have called it “Come, Warm My Igloo”, likewise that Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar would have become “The Beast is not for Beating”. His most successful releases were in the exploitation and horror genres, and include The Corpse Grinders (Ted V Mikels, 1971) and Supervixens (Russ Meyer, 1975). Balch also worked as the programmer for the Jacey (Piccadilly) and Times (Baker Street) cinemas. He could often be seen collecting tickets and projecting a mixture of blue movies, surrealist and foreign classics, and British premieres such as Samuel Fuller’s Shock Corridor (1963). A real old fashioned entrepreneur, he hoped to catch the attention of shopping passers-by with a short Canadian documentary on slimming, and was never downhearted by an empty house for Yoko Ono’s No. 4 (bottoms) film.

Haxan was an unusual Swedish black and white, silent feature film made by the progressive and promising Danish director Benjamin Christensen in 1918-21. Its quasi-documentary style employed startling lighting effects to depict the power of witchcraft through the Middle Ages. It is obviously a personal work, and it’s a wonder that the director himself wasn’t burnt at the stake when he inflicted his fantasies onto the unsuspected public in the early days of cinema. The director went on to work for UFA in Germany before an ineffectual move to Hollywood in 1925. Haxan was originally released silent at 108 minutes in 1922, being re-released with a music track in 1941. In 1968, Antony Balch rediscovered the film and commissioned Burroughs to narrate new soundtrack for a new UK release bearing the title Witchcraft through the Ages. A modern jazz score by French violin virtuoso Jean-Luc Ponty accompanied Burroughs monologue. It is this condensed 87 minute version that is most often screened to this day.

Antony Balch continued to distribute films and campaign against censorship throughout the 1970s, and died of stomach cancer on 6 April 1980, aged 42. Soon after, Brion Gysin contacted Genesis P’Orridge (who first became acquainted with Burroughs in 1973) suggesting that he should visit Balch’s office in Soho and rescue the films and documentation before they were thrown out by unscrupulous business partners. Legend tells that half the films, believed worthless and insignificant, were already in a skip outside when he arrived. 28 cans of film, including 18 cans of 35mm footage shot for Guerrilla Conditions, were rescued from certain destruction. With the approval of William Burroughs, Genesis P’Orridge personally cared for, promoted and meticulously documented the film materials throughout the 1980s. His efforts led to the discovery of a short colour sequence now known as William Buys a Parrot, a reel of Brion Gysin painting titled “Transmutations”, and many more sequences extending the experiments in character transformations of Bill and Tony, which use superimposition, mirrors and optical distortions. With assistance from Derek Jarman, P’Orridge edited together a video version of Ghosts at #9 (from the unseen Guerrilla Conditions footage) and assembled a soundtrack from tapes made by Balch, Burroughs, Gysin and Sommerville. In addition to screenings, he coordinated video releases in the UK through Jettisoundz / Visionary and in America through Sheldon Renan’s Mystic Fire label. In the late 1980s, P’Orridge sold all the original materials to William Burroughs and the writer Barry Miles. It is understood that the rights are now administrated by James Grauerholz of William S. Burroughs Communications in Kansas. Towers Open Fire and The Cut-Ups were theatrically distributed on 16mm for some time by Connoisseur Films, and are currently available from the BFI.

Chappaqua

One other notable experimental film collaboration by Burroughs in the 1960s was Chappaqua, a personal project of the Avon cosmetics heir Conrad Rooks, was born in Kansas City in 1934. Following a term in the marines, he spent two and a half years in film and television school and co-founded Exploit Films to produce three nudie features. An alcoholic and drug addict from an early age, he gravitated towards the beatnik fringe, and in the early 1960s, Rooks spent time in Manhattan hanging out with characters like filmmaker and anthropologist Harry Smith. He began a correspondence with William Burroughs in 1963 and subsequently bought an option on the film rights to “The Naked Lunch”. He abandoned plans to make the film but recognised Burroughs’ potential acting talent and cast him as Opium Jones, the spirit of junk, in Chappaqua.

Using a substantial portion of his family wealth, he shot this feature over 2 years between January 1964 and April 1966, loosely basing it on an autobiographical poem he wrote about experiences of heroin withdrawal. Drawing on a wide range of the subculture for assistance, its credits read like an underground telephone directory. Ian Sommerville worked on sound, Robert Frank was director of photography, David Larcher shot the production stills, a specially commissioned score by Ornette Coleman was dumped in favour of one by Ravi Shankar, and Burroughs, Ginsberg and Moondog all appear. The film, a suitably confused and psychedelic mixture of facts and fiction, was awarded the Silver Lion in Venice 1966. Universal bought the distribution rights but failed to promote the film, prompting Rooks to spend even more money buying it back for a limited release in 1968. John Trevelyan and the BBFC obtained psychiatric advice on the portrayal of drug addiction before passing it for screenings in the UK. Now available on video, it is seen to be a valuable and evocative document of the period.

Mark Webber, 2001

Back to top

Date: 15 April 2001 | Season: Century City

LIKE SEEING NEW YORK FOR THE FIRST TIME

Sunday 15 April 2001, at 3pm

London Tate Modern

LIKE SEEING NEW YORK FOR THE FIRST TIME: 1

Six Extraordinary Films of Manhattan in the 60s & 70s

Two programmes of films selected by Mark Webber for the Tate Modern exhibition “Century City: Art and Culture in the Modern Metropolis” (1 February – 29 April 2001), presenting six unique views of New York in the 60s and 70s.

NEW YORK PORTRAIT: CHAPTER 1

Peter Hutton, USA, 1978-79, b/w, silent, 16 min

Hutton’s black and white haikus are an exquisite distillation of the cinematic eye. The limitations imposed – no colour, no sound, no movement (except from a vehicle not directly propelled by the filmmaker), no direct cuts since the images are born and die in black – ironically entail an ultimate freedom of the imagination. If pleasure can disturb, Hutton’s ploys emerge in full focus. These materialising then evaporating images don’t ignite, but conjure strains of fleeting panoramas of detached bemusement. More than mere photography, Hutton’s contained-within-the-frame juxtapositions are filmic explorations of the benign and the tragic. (Warren Sonbert)

Hutton’s most impressive work, the filmmaker’s style takes on an assertive edge that marks his maturity. The landscape has a majesty that serves to reflect the meditative interiority of the artist independent of any human presence. New York is framed in the dark nights of a lonely winter. The pulse of street life finds no role in New York Portrait; the dense metropolitan population and imposing urban locale disappear before Hutton’s concern for the primal force of a universal presence. With an eye for the ordinary, Hutton can point his camera toward the clouds finding flocks of birds, or turn back to the simple objects around his apartment struggling to elicit a personal intuition from their presence. Hutton finds a harmonious, if at times melancholy, rapport with the natural elements that retain their grace in spite of the city’s artificial environment. The city becomes a ghost town that the filmmaker transforms into a vehicle reflecting his personal mood. The last shot looks across a Brooklyn beach toward the skyline of Coney Island’s amusement park. The quiet park evokes the once frantic city smothered by winter. Nature continues its eternal cycles impervious to the presence of man, the aspirations of society, or the decay of the metropolis. (Leger Grindon, Millennium Film Journal, 1979)

STILL

Ernie Gehr, USA, 1969-71, colour, sound, 53 min

In Still, Gehr’s picture of place feels most like home. From the perspective of a ground-floor window, we look out at a bit of Lexington Avenue just south of 31st Street in Manhattan, the one-way traffic and the people going by, crossing the street, entering and leaving a luncheonette – nothing out of the ordinary – except for the superimpositions, the ghostly presences, of other people, other cars and buses and trucks inhabiting the same place. These are not supernatural but material ghosts, conjured without mystification or fuss by double exposures done in the camera. And yet this technique works wondrously to evoke the mysterious interplay of different times in the life of a place, times of the day and of the year, pieces of personal and social history that have here come to pass. This is a film about place in time, and in time we sense that this is a place happily haunted by its ghosts. One admirer, the dramatist Richard Foreman, called Still an intimation of paradise. It is paradise found in the yellow of cabs and the green of a tree across the street, in the way that things are seen to fit, body and ghost, into the fabric of the world. It is paradise found in the kind of detachment that is most deeply involving. Still begins in silence and in winter. The tree is bare, the light is low, and the wintry white of a parked car stands at the centre of the screen. Then suddenly the tree is in bloom and the light is bright, the long shadows of winter are gone and the sounds of the city are heard. Wintry white gives way to the double-exposed spring yellow of two superimposed pairs of parked taxicabs. If the fluorescent-lit interior of an institutional corridor is “an unlikely vantage point to view the dawn,” as Sitney remarks in his book on Gehr, “a stretch of Lexington Avenue in the 30s is almost as unlikely a spot to hail the coming of spring.” But we work with what we’ve got, and from the view out the window Gehr composes an urban salute to spring as stirring as any bucolic one. (Gilberto Perez, Yale Review, October 1999)

REAL ITALIAN PIZZA

David Rimmer, Canada, 1971, colour, sound, 10 min

Taken between September 1970 and May 1971, with the unmoving camera apparently bolted to the window ledge, this film, a ten-minute eternity, chronicles what takes place within view of the lens. The backdrop is a typical New York pizza stand, the actors are selected New Yorkers who happened to be there during the half year, the plot is the somewhat sinister aimlessness of life itself. (Donald Ritchie, Museum of Modern Art, New York)

David Rimmer has quietly placed his camera in the blind spot everyone walks past. A fire engine, lights flashing, stops for the firemen to dash in to get some pizza to take to the fire … You haven’t been to New York ’til you’ve seen Real Italian Pizza. (Gerry Gilbert, BC Monthly)

Back to top

Date: 4 May 2001 | Season: Larry Jordan | Tags: Oberhausen Film Festival

FLOATING THROUGH TIME: THE FILMS OF LARRY JORDAN

4 & 5 May 2001

Oberhausen Lichtburg Filmpalast

Cinematic Duplicity: The Twin Worlds of Larry Jordan

Whether concerned with reality or the unconscious world, each work by Larry Jordan is a small wonder, a unique excursion both outwards and within. Although best known for his fragile animations, he has continued to work with live photography throughout his life. In his animations, images are liberated of their intrinsic meanings allowing the viewer to derive their own interpretation as the filmmaker travels along his inner journey. By contrast, Jordan’s live action cinematography frequently captures a direct sense of place, retaining a connection to the world at large. Presenting raw, untreated footage, he documents the essence of his world. All of his work conveys a sense of exploration and self-discovery, an aspiration to higher things. Images may be inspired by dream visions, or arise from a state of complete openness. Often working in an extemporised manner, by embracing chance and fortune, Jordan is free to wander through an infinite range of possibilities.

“Animation is, I guess you’d say, my interior world, and the live films are pretty much my interface with the real world. I may use some quick cutting, but I don’t use a lot of optical printing or manipulation of the image. I like to see the raw image from the real world, that excites me on the screen more than a manipulated image. Even in animation, I like to see flat-out what’s there in front of the camera, and see if the bold un-art-ised image can’t be the strongest thing. I used to feel I had to get out of there and work with people in the world, to keep that connection going. I couldn’t just stay in the studio and do animation all the time, so I’d go out to try to capture ‘spirit of place’. The world is miraculous, but people working in film don’t feel that’s enough, I guess, not exciting enough to an audience. I’ve tried to find ways of putting the real world, the way it really is, into the live films at some level.”

Jordan’s interest in film began while studying literature at Harvard. He attended the university’s film series, seeing Cocteau, Clair and Eisenstein, as his high school friend Stan Brakhage was beginning his own serious investigation of the medium. Jordan realised that his interest was more with the image than the word, and on returning to Denver he began working the tradition of the avant-garde trance film. Moving to San Francisco, he became involved in a creative group that included Robert Duncan, Jess Collins, Philip Lamantia, Kenneth Rexroth and Michael McClure. Inspired by this artistic milieu of poets and artists working outside the mainstream, Jordan shot Visions of A City, a portrait of a place and that of a friend, combining trance vision with a sense of alienation.

“The city is hard and impersonal, hence, the reflected image. The man emerges out of this, is there for a little while, and then is absorbed back under the hard surface of the city. What’s really important to me is that it’s a little glimpse of San Francisco in ’57 – it’s hard to find that anywhere. It’s also a portrait of Michael McClure in 1957, the only one that moves. Film has done very badly at documenting the world as it really is, whereas still photography has done very well. So much energy in film has gone into the mental construct, the script, the drama, the fairytale; so what have you got that’s a time machine ? You’ve got Man with a Movie Camera, Berlin, Symphony of a City and a few films of New York.”