Date: 27 October 2003 | Season: London Film Festival 2003 | Tags: London Film Festival

KEN JACOBS MASTERCLASS

Monday 27 October 2003, at 6:30pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

BENEATH CONSIDERATION: A LECTURE ON FAILURE

Ken Jacobs has been one of the key figures of artist filmmaking of the past five decades. As a contemporary of Kenneth Anger, Stan Brakhage and Jonas Mekas, he was at the forefront of the New America Cinema movement that defined ‘avant-garde film’ in the 50s and 60s. Jacobs taught as Professor of Cinema at SUNY Binghampton for over 30 years, where his last course before retirement was on the subject of ‘Stupidity’. At the LFF in, 2000, he presented two sold out ‘Nervous System’ projection performances and this year he returns to London with his 6-hour video Star Spangled To Death.

In this masterclass on ‘failure’ he will argue that in achieving socially set objectives, we rule out the possibility of unimaginable discoveries. Much of what passes for success can lead to predictability, conceit and the curse of celebrity, while there can be many triumphs as a result of ineptitude and confusion. Incredible things can happen by following the ‘wrong turn into adventure’. The illustrated talk will include screenings and references to the work of filmmakers including Erich von Stroheim, Charlie Chaplin and Oscar Micheaux.

Back to top

Date: 31 October 2003 | Season: London Film Festival 2003 | Tags: London Film Festival

THE DECAY OF FICTION

Friday 31 October 2003, at 11:30pm

London National Film Theatre NFT1

Pat O’Neill, The Decay of Fiction, USA, 2002, 74 min

Pat O’Neill describes The Decay of Fiction as an intersection of fact and hallucination in an abandoned luxury hotel. The hotel in question is The Ambassador in Hollywood, once the grand playground of politicians and movie stars, now shabby and awaiting demolition. Against this decaying glamour, O’Neill reconstructs and reconfigures a noir-tinged narrative, in which stories slip between fact and fiction, memory and urban myth. A tall, elegant blonde stands on the terrace of her bungalow, smoking and watching the sunrise. A group of sinister men arrive and ask for Jack. Guests come and go, and so do the cops… Renowned for his brilliant and unique compositional processes using optical printing to articulate different layers in the film frame, O’Neill draws on over three decades of experimentation to compose this sensuous exploration of the boundaries of believability. (Sandra Hebron)

Screening with

Janie Geiser, Ultima Thule, USA, 2002, 10 min

An animated journey into uncharted territory. ‘A small silver plane navigates an ultramarine storm, flying over cloud-covered hills; an unlikely ferry to Ultima Thule: the farthest point, the limit of any journey.’

PROGRAMME NOTES

THE DECAY OF FICTION

Friday 31 October 2003, at 11:30pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

ULTIMA THULE

Janie Geiser, USA, 2002, 16mm, colour, sound, 10 min

A small silver plane navigates an ultramarine storm, flying over cloud-covered hills, an unlikely ferry to Ultima Thule: the farthest point, the limit of any journey. The seduction of immersion in blue is too strong to avoid, the land fills with water, time loses its line. This film grew out of my strong attraction to a certain blue that I found in an animated film sequence. I wanted to place images in that blue rain, and an aeroplane made its way in. I followed the plane through the night storm to this unknown destination. (Janie Geiser)

THE DECAY OF FICTION

Pat O’Neill, USA, 2002, 35mm, colour, sound, 74 min

The Decay of Fiction is an intersection of fact and hallucination in an abandoned luxury hotel. The hotel is in Hollywood. The walls of the Ambassador are cracked and peeling, the lawns are brown, and mushrooms grow in the damp carpets of the Cocoanut Grove. The pool is empty, and the ballroom where Bobby Kennedy died is shuttered and locked. A tall, elegant blonde stands transparently on the terrace of her bungalow, smoking and watching the sunrise. Voices and tinkles waft across the lawn. A contingent of vaguely sinister men arrive and ask for Jack. Jack is expecting trouble, but not this kind of trouble. Louise, a guest, replays a nightmare in which she drowns Pauline so that she can marry Dean. The sun sets and rises again. Two detectives seem to turn up everywhere, searching for Communist literature and telling one another pointless stories of underworld intrigue. In the kitchens and behind the scenes the daily routine continues, individuality melts, and workers fuse with their jobs. Winter passes, and then another summer, and finally it is Halloween, and there is a costume ball which claims the life of Rhonda the evasive soprano. And then the building comes down in a clatter of Spanish tiles and concrete, and fact has finally become fiction, once again.

I scribbled the words “The Decay of Fiction” on the back of a notebook almost forty years ago, tore it off and framed it fifteen years later, and have wanted ever since to make a film to fit its ready-made description. To me it refers to the common condition of stories partly remembered, films partly seen, texts at the margins of memory, disappearing like a book left outside on the ground to decompose back into the earth.

The film takes place in a building about to be destroyed, whose walls contain (by dint of association) a huge burden of memory: cultural and personal, conscious and unconscious. To make the film was to trap a few of its characters and some of their dialog, casting them together within the confines of the site. The structure and its stories are decaying together, and each seems to be a metaphor for the other.

I am interested in exploring the boundaries of believability. The narrative tradition insists that, no matter how fantastic the story, its surface must be seamless. By contrast, I call attention to the artifice, all the staged aspects, and allow the well-worn stories to slip over and through one another. The film’s intention could be described as wanting to take stories off the screen and into the imagination. I like to work within the gaps between reality and story, to look at what is going on around the story, its context, and to make that a part of my conversation with the audience.

—Pat O’Neill

Back to top

Date: 1 November 2003 | Season: London Film Festival 2003 | Tags: London Film Festival

VIDEO VISIONS

Saturday 1 November 2003, at 2pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

Ezra Eeman, Look at me standing here, Belgium, 2001, 8 min

An apparently mundane view of a pedestrian area … what is happening? Image seamlessly sticks and cuts, sound drifts from super-realism to atmospheric score. Time suspends as the sense of alienation and displacement distends. The centre of the city is a lonely place.

Pierre-Yves Cruaud, Le Silence est en Marche, France, 2001, 4 min

A horizontal arrangement of bands of light slowly gives way to emerging human forms, seen from above, passing through the frame. Though digital manipulation, a situation is suggested, but never seen. Sound is a sonic crackle and pulse.

Michaela Schwentner, Jet, Austria, 2003, 6 min

Dynamic recycling of treated and degraded video, structured to a track by electronic sound artists Radian.

Keiichi Tanaami, WHY Re-Mix, 2002, Japan, 2002, 10 min

Footage of a boxing match is reduced to printed still images and its constituent dots are enlarged and contrasted into an optical moiré. Assault not insult. A blitz of sound and image by Japanese animator, graphic designer Tanaami, based on his 1975 film Why.

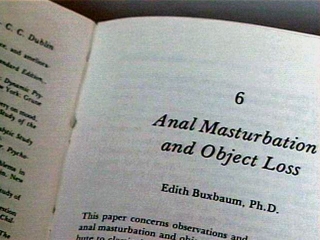

Steve Reinke, Anal Masturbation & Object Loss, USA, 2002, 6 min

Reinke protests the ubiquity of theory and conjecture, while proposing a new art school where nothing is produced except discourse. To protect the students from undue influence, the pages of the library books must be glued together.

George Kuchar, Forbidden Fruits, USA, 2002, 15 min

George’s video diaries continue, slipping between reverie and reality, with a visit to the SF Art Institute, dinner in Chinatown and a lush daydream of sprouting seduction. Sap rises and spring swings when a tour of a friend’s garden detours into flights of floral fantasy.

Peter Rose, The Geosophist’s Tears, USA, 2002, 8 min

Travelling shots from a cross-country road trip are tiled and matted to propose impossible vistas.

Gerhard Geiger, Franz und Klara, Germany, 2003, 4 min

Geiger seeks an equivalent, format-specific editing style for digital video, to those techniques he has used for concentrated 16mm filmmaking.

Wago Kreider, Marvelous Creatures, USA, 2003, 3 min

Gaudily lit waxworks of Hollywood icons and the animals of a diorama, rapidly intercut with their subjects’ natural environments – classic movies and the zoo.

Jeroen Offerman, The Stairway at St. Paul’s, Netherlands-UK, 2002, 9 min

Inspired by rumours of satanic messages hidden in rock records, Offerman memorised and performed the vocal track of Led Zeppelin’s ‘Stairway to Heaven’ in its entirety, backwards. A continuous shot taped outside St. Paul’s Cathedral and then reversed to present the classic song in a skewed, but legitimate, new way. Sincere, admirable, and very, very funny.

Tony Cokes & Scott Pagano, 5%, USA, 2001, 10 min

Critical commentary on the business practices of the music industry, ripping apart the illusory promises made to the consumer.

Benny Nemerofsky Ramsay, I Am A Boyband, Canada, 2002, 6 min

A music video for a group of cloned pop stars. Nemerofsky Ramsay splits his own personality to create the perfect boy band of four distinct and desirable youngsters. All the ingredients are there; and it makes so much sense on a commercial level. Their song of heartbreak is an Elizabethan madrigal, ‘Come Again, Sweet Love’ by composer John Dowland (1563-1626).

PROGRAMME NOTES

VIDEO VISIONS

Saturday 1 November 2003, at 2pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

LOOK AT ME STANDING HERE

Ezra Eeman, Belgium, 2001, colour, sound, 8 min

An apparently mundane view of a pedestrian area … what is happening? Image seamlessly sticks and cuts, sound drifts from super-realism to atmospheric score. Time suspends as the sense of alienation and displacement distends. The centre of the city is a lonely place. —Mark Webber

LE SILENCE EST EN MARCHE

Pierre-Yves Cruaud, France, 2001, colour, sound, 4 min

Barriers restrict the living space of more or less human apparitions. We witness the development of life forms that are already fairly regimented. —Pierre-Yves Cruaud

JET

Michaela Schwentner, Austria, 2003, colour, sound, 6 min

This video’s exhilarating dynamism results from a precisely composed interplay of colour and form which structures the viewer’s perception of it significantly. Michaela Schwentner’s work method closely resembles that of electro-acoustic sound artists Radian, who employ a variety of painterly elements that are allowed to interact, overlap or contrast. —Christa Benzer

WHY RE-MIX, 2002

Keiichi Tanaami, Japan, 2002, colour, sound, 10 min

Footage of a boxing match is reduced to printed stills, whose constituent dots are enlarged and contrasted into an optical moiré. Audio-visual barrage of sound and image by Japanese animator , graphic designer Tanaami, based on his 1975 film Why. Assault not insult. —Mark Webber

ANAL MASTURBATION & OBJECT LOSS

Steve Reinke, USA, 2002, colour, sound, 6 min

Ever on the lookout for learning opportunities, Reinke envisions an art institute where you don’t have to make anything, and with a library full of books glued together. All the information’s there – you just don’t have to bother reading it! —New York Video Festival, 2002

FORBIDDEN FRUITS

George Kuchar, USA, 2002, colour, sound, 15 min

The foliage and sprouting of urban greenery becomes the subject of this celebration to all things pollinated. The video explores hidden gardens that lie sequestered amid an array of dwellings inhabited by the not so rich and famous. Felines creep amid the blossoms as human entities enrich the soil with their leaking desires. —George Kuchar

THE GEOSOPHIST’S TEARS

Peter Rose, USA, 2002, colour, sound, 8 min

Shot during a seven-week cross-country road trip in the aftermath of September 11th, the work is operatic in ambition and offers a complex meditation on the iconography of the American landscape. Drawing on the stratagems of the early geosophists, who believed that through the operation of a mysterious instrument landscapes might be placed in an emotionally meaningful correspondence with one another, the work uses a variety of visual algorithms to propose and discover surprising structural features of the uninhabited American landscape. Sounds for the work were produced by a remarkable antique slide rule, dating from 1895, that was untouched for over forty years and whose peculiar threnody is both mournful and rhapsodic. In its fractured and phantasmagoric reworkings of the horizon, the work offers us unstable metaphors for the state of the union and a respectful homage to the traditions of painting. —Peter Rose

FRANZ UND KLARA

Gerhard Geiger, Germany, 2003, colour, sound, 4 min

Geiger seeks an equivalent editing style for digital video, to those techniques he has used for 16mm film. Using the same footage shot at a family house party, he presents first the concentrated short film (twice for our assimilation) and then the more recent video version. —Mark Webber

MARVELOUS CREATURES

Wago Kreider, USA, 2003, colour, sound, 3 min

From the taxidermied bestiary of a natural history museum to the life-like waxworks that haunt our pop culture memories, the convulsive beauty of animals oscillates between plenitude and punishment, attraction and repulsion, life and death. In a series of photographic shocks that flash an image of the fixed-explosive, Marvelous Creatures signal the uncanny correlation of erotic and destructive impulses. They bear witness to a primordial trauma, a confusion between the animate and the inanimate, the biological and the mechanical, Eros and Thanatos. —Wago Kreider

THE STAIRWAY AT ST. PAUL’S

Jeroen Offerman, Netherlands-UK, 2002, colour, sound, 9 min

It’s time to dive into your record collection and find out if it was all true. But first let us watch this video. Turn up the volume and remember the first time you smoked a cigarette… —Jeroen Offerman

5%

Tony Cokes & Scott Pagano, USA, 2001, colour, sound, 10 min

5% is a ten-minute work that questions the cult of pop stardom, deconstructs music industry practices, considers the problematics of live performance, and suggests other, more anonymous working strategies. For this work I decided to collaborate closely with musician, media artist, and designer Scott Pagano who, along with Marc Pierson, currently form the core of SWIPE. Our idea of generic music came out of a belief that pop music was more about life under post-industrial commodity capital than it was about ‘love’, ‘emotion’ or ‘personal expression’. Narratives of superstardom were the grease that kept the idiotic grind looped, moving in place. The soundtrack is two recent SWIPE tracks: “mm_2” and “1cc_v2+”. —Tony Cokes

I AM A BOYBAND

Benny Nemerofsky Ramsay, Canada, 2002, colour, sound, 6 min

What are the ingredients for a boy band? A cute tune, dance moves and of course four handsome hunks, each with their own look … A cloned boyband co-opts an Elizabethan madigral to express its heartbreak over lost love. —Benny Nerofsky Ramsay

Back to top

Date: 1 November 2003 | Season: London Film Festival 2003 | Tags: London Film Festival

LIGHT TRACES

Saturday 1 November 2003, at 4pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

Julie Murray, Untitled (Light), USA, 2002, 5 min

A night-time memorial to the World Trade Centre site and its ‘towers of light’.

Guy Sherwin, Animal Studies, UK, 1998-2003, 25 min

A series of meditations on nature and the animal kingdom, comprising both physical and metaphysical reflection. Each has the subtle, granular pulsing that makes it seem as though these could be the first rolls of film ever wrenched through a camera.

Karl Kels, Prince Hotel, Germany, 1987-2003, 8 min

A portrait of New York’s Bowery and its time-warn occupants. Though no longer solely a refuge for alcoholics and the lost, some of those characters remain, and their world is revered by Kels’ camera, displaying humour and a deep sense of camaraderie.

Jimmy Robert, Embers, UK, 2003, 7 min

Using the modest Super-8 gauge to film his immediate personal surroundings, Jimmy Robert has developed a profound personal style. Fleeting moments are combined in editing, evoking moods through the juxtaposition of images.

Nathaniel Dorsky, The Visitation, USA, 2002, 18 min

‘The Visitation is a gradual unfolding, an arrival so to speak. I felt the necessity to describe an occurrence, not one specifically of time and place, but one of revelation in one’s own psyche. The place of articulation is not so much in the realm of images as information, but in the response of the heart to the poignancy of the cuts.’

PROGRAMME NOTES

LIGHT TRACES

Saturday 1 November 2003, at 4pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

UNTITLED (LIGHT)

Julie Murray, USA, 2002, colour, sound, 5 min

A moving reflection on September 11, Untitled (Light) finds beauty in minutiae, breaking down the skyward searchlights memorializing the fallen towers into a constellation of illuminated dust motes. —Onion City Film Festival, 2003

ANIMAL STUDIES

Guy Sherwin, UK 1998-2003, b/w, silent, 25 min

A variable set of perceptual studies on the inconsequential movements of animals. The films are made partly in the camera and partly in the printer, and most are derived from a single take. Fluctuations of light, geometry and time reveal what might be hidden in the photographic depths of the material. My filmic interest in animals is that they are unselfconscious, authentic, and don’t act. This is part of an ongoing series of films which developed out of the Short Film Series, and can be shown in any order or number, giving an openness of connection between images, ideas, thoughts, themes. —Guy Sherwin

PRINCE HOTEL

Karl Kels, Germany 1987-2003, b/w, silent, 8 min

In 1986 Kels received a fellowship that allowed him to study at Cooper Union in New York. During his stay there, Kels spent some six months at the Bowery in Lower Manhattan. He began hanging out with the less fortunate who eke out an existence in cheap hotels or on the street, and became friendly with many of them. In the lives of the mostly male alcoholics who survive on open camaraderie and cheap alcohol, he discovered a rich unstaged world, which he slowly started to film. Bowery / Fragment [the working title for Prince Hotel] is but a short fragment of what a final film on this subject could offer, yet it stands by itself and clearly bears the director’s marks. Against the background of a run-down Prince Hotel we see men who pass time together, deliberately portrayed by Kels’ clear eye for framing and detail, and yet whose acts and movements cannot be controlled. —Miryam Van Lier, Millennium Film Journal

EMBERS

Jimmy Robert, UK, 2003, colour, silent, 7 min

Using the modest super-8 gauge to film his immediate personal surroundings, Jimmy Robert has developed a profound personal style. Fleeting moments are combined in editing, evoking moods through the juxtaposition of images. —Mark Webber

THE VISITATION

Nathaniel Dorsky, USA, 2002, colour, silent, 18 min

The Visitation is a gradual unfolding, an arrival so to speak. I felt the necessity to describe an occurrence, not one specifically of time and place, but one of revelation in one’s own psyche. The place of articulation is not so much in the realm of images as information, but in the response of the heart to the poignancy of the cuts. —Nathaniel Dorsky

Back to top

Date: 1 November 2003 | Season: London Film Festival 2003 | Tags: London Film Festival

ILLUMINATION

Saturday 1 November 2003, at 7pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

Rebecca Meyers, Glow in the Dark (January-June), USA, 2002, 6 min

A somnambulant chronicle of night-time luminosity, and the sounds that keep us awake in the lonely twilight.

Goh Harada, Lampenschwarz, Japan-Germany, 2001, 12 min

Tactile, imageless film created using clear film and black pigment, which has been manually rubbed into a layer of transparent silicone. In projection, it becomes a rapid and infinitely complex hypnagogic vision.

Fred Worden, If Only, USA, 2003, 7 min

Points of light burst through the darkness in a surge of abstract motion. Luminous stimulation for the subconscious.

Ichiro Sueoka, I am Lost to the World, Japan, 2003, 7 min

Re-appropriation of anonymous footage shot in Kyoto 1934; its fractured images ravaged by chemical and physical decay. ‘Film is not an immortal document; it is a vanishing existence.’

Thomas Draschan, Encounter in Space, Austria-Germany, 2003, 7 min

Science, the space race and more earthy pursuits: formal and narrative strategies applied to found footage to create a supernatural adventure.

James Otis, Common Knowledge, USA, 2002, 2 min

‘Upbeat, fast-paced, crowd-pleasing investigation of marketing and the original sin, based on a South African apple juice commercial. The sound track is an obsessively synchronised, mad marimba version of the old mission hymn, ‘From Greenland’s Icy Mountains’.’

Sandra Gibson, Outline, USA, 2003, 6 min

Direct cinema barrage of light and colour, in cinemascopic glory.

Louise Bourque, Jours en Fleurs, Canada, 2003, 5 min

A symphony of nature told in a shower of golden colours that reveal a microcosm of cellular structures. Film emulsion transfigured by incubation in menstrual blood.

Trish Van Huesen, Resurrection, USA, 2002, 3 min

The emergence of consciousness as beatific reawakening. A whiff of the ‘The Passion of Carl Th. Dreyer’ somehow embodied within a hand processed, scratched, painted and bleached Super-8 blow-up. Music by cyclic Icelandic wonderkind Eyvind Kang.

Lewis Klahr, Daylight Moon, USA, 2002, 14 min

Using collage animation, Klahr conjures up an evocative, hermetic world. The sense of quiet melancholy suggests a loss of innocence, both personal and collective, which is pictorially represented by the 1950s consumer boom.

PROGRAMME NOTES

ILLUMINATION

Saturday 1 November 2003, at 7pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

GLOW IN THE DARK (JANUARY-JUNE)

Rebecca Meyers, USA, 2002, 16mm, colour, sound, 6 min

Radiators clang while spheres and cypridina phosphoresce. A rubber ball held up to light becomes a snowy crystal. Looking out and up when the sun is down. Home science experiments and other attempts to see with the camera in the dark. —Rebecca Meyers

LAMPENSCHWARZ

Goh Harada, Japan-Germany, 2001, 16mm, b/w, silent, 12 min

Black surface made with black pigment meets white surface created by the projection lamp. The film Lampenschwarz was made solely by manual work only using black pigment (Lampenschwarz), transparent glue and blank film. These materials were brought onto the transparent film with the tips of the fingers, frame by frame. This film shows 17,000 of these different black and white images through the rapid speed of the projector, thus creating ‘black and white movements’. —Goh Harada

IF ONLY

Fred Worden, USA, 2003, 16mm, b/w, silent, 7 min

The bubble shaped orb of the human head, perched atop its touchy-feely transport system has seven moist oval openings through which everything outside comes in: two eyes, two nostrils, one mouth and two ears. Inside the bubble head, bubble universes spawn ad infintum and the only passable direction is directly into the steady headwinds of an ever advancing infinity of veils. A high wire bobbing and weaving just to stay upright. These artful if endless veil penetrations are at once the human job description as well as nature’s shot at vindicating the transient in the face of the impassive infinite. Nature makes the orifices moist so things can stick, at least momentarily. The intoxicated camera operator shoots the moon slipping through the barren trees. The rabbit hole’s light shadow appears and he obliges, head first, no looking back. His cranium (like yours) is packed with illusions, but down the rabbit hole they treasure the same just so long as they’re custom fabricated, hand tooled and conscious. Down this hole, stalking the unforeseen non-translatable is all. Join in here. —Fred Worden

I AM LOST TO THE WORLD

Ichiro Sueoka, Japan, 2003, 16mm, b/w, sound, 7 min

This title is quoted from the poetry of Friedrich Rueckert (“Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen”). This German romanticist poet wrote of the sadness of disappearance. An anonymous amateur cineaste shot and recorded the some scenes of Kyoto in 1934, but the films are suffering from vinegar syndrome, since they have been badly stored. The films were just falling into decay, and would probably only disappear, without looking back to anyone. ‘Film’ is not an immortal document, but a vanishing existence. —Ichiro Sueoka

ENCOUNTER IN SPACE

Thomas Draschan, Austria-Germany, 2003, 16mm, colour, sound, 7 min

Encounter in Space relates the story of a man and his alter egos, abandoned in the midst of an unknown extraterrestrial region, immersed in the sinister light of an unholy radiation, which arouses in him sexual craving and human desire. He has to encounter a number of adventures and to give proof of his potency, while having to cope with an eye operation and several other incidents. He is noticeably getting lost in the battles among his alter egos. Eventually, part of his personality leaves the planet, and the part of his personality that remains behind is able to embark in peace on a quest for new amusements. —Thomas Draschan

COMMON KNOWLEDGE

James Otis, USA, 2002, 16mm, colour, sound, 2 min

Upbeat, fast-paced, crowd-pleasing investigation of marketing and the original sin, based on a South African apple juice commercial. The sound track is an obsessively synchronised, mad marimba version of the old mission hymn, “From Greenland’s Icy Mountains”. —James Otis

OUTLINE

Sandra Gibson, USA, 2003, 35mm, colour, silent, 6 min

Defining the shape of everyday objects (ferns, forks and flowers), the strip of film was unwound on the studio floor and decoratively stencilled. At 24 frames per second, the objects dissolve into a filmic downpour. —Luis Recoder

JOURS EN FLEURS

Louise Bourque, Canada, 2003, 16mm, colour, sound, 5 min

A reclamation of flower-power in which images of trees in springtime bloom are subjected to the floriferous ravages of menarcheal substance. The title is based on an expression from my coming of age in French Canada, where girls would refer to having their menstrual periods as ‘être dans ses fleurs’. As a result of incubation in menstrual blood for several months, the original images on the emulsion undergo violent alterations. The shedding of the unfertilised womb depredates the fertilised blossoms and substitutes its own dark beauty. From the dissolution of the pro-filmic, the scale shifts abruptly and kaleidoscopically from the macro to the microcosmic and with it another representation of nature emerges. —Louise Bourque

RESURRECTION

Trish Van Huesen, USA, 2002, 16mm, colour, sound, 3 min

A hand processed Super-8 film, where individual frames have been scratched, painted and bleached in order to portray the emergence of consciousness. —Trish Van Huesen

DAYLIGHT MOON

Lewis Klahr, USA, 2002, 16mm, colour, sound, 14 min

There are things I could say about Daylight Moon but very few I want to before someone has seen it. But I will say this: of all the films I’ve made using collage to muck around in the past, this one gets the closest to what I’m after. —Lewis Klahr

Back to top

Date: 1 November 2003 | Season: London Film Festival 2003 | Tags: London Film Festival

IMITATIONS OF LIFE

Saturday 1 November 2003, at 9pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

Mike Hoolboom, Imitations of Life, Canada, 2003, 75 min

A series of topical news headlines sound like it might as well be the end of the world, but this is 1993, the year the filmmakers’ nephew was born. It’s an event that leads him to contemplate the ceaseless urge to photograph and be photographed. For Hoolboom, this compulsion indicates our discontentment with the world, which is compensated by reproducing it as ‘experience in a crisis-proof form’. Imitations of Life is a 10-part suite of dreams and memories that integrates original footage with instantly recognisable images from commercials, cinema classics and recent blockbusters. In Jack’s early years, the filmmaker sees (and shows us) the world through a child’s eyes. Later, this sense of open wonder is retained, though tempered in the knowledge that modern life doesn’t permit us such indulgence. We are ‘the children of Fritz Lang and Microsoft’, striving to give our lives shape and meaning through photographs, tv and movies. Through a vast wealth of adopted images, this video questions the values of lives lived through the lens. If movies carry our collective baggage and teach us about the world around us, do they hold us back from inventing the future?

Also Screening: Saturday 25 October 2003, at 8:30pm, London ICA2

PROGRAMME NOTES

IMITATIONS OF LIFE

Mike Hoolboom, Canada, 2003, video, colour, sound, 75 min

Expanding on the structure of Panic Bodies, with its discrete but interconnected shorts, the latest found-footage feature from Mike Hoolboom is a ten-part meditation on childhood, visual representation and the future in a world of pictures. Breathtaking in its encyclopaedic recycling and appropriation, the film moves beyond scratch video, assemblage and recontextualisation; in Hoolboom’s words it “strains childhood through a history of reproduction, culling pictures from the Lumières to the present day in order to find the future in the past.” Much more than just a poetic essay on mediation and simulation at the end of history, the film situates the ethical challenges of the future within the context of picture making, pointing to our current crisis as one of (a failure of) imagination, representation and technology.

Already acclaimed as a short in its own right, Jack works as the heart of the film, with Hoolboom’s familiar, wryly wise voice-over recounting visits with his nephew as we witness Jack growing up in processed Bolex images. Here we see possibility, for Jack makes happiness his profession and ponders if politics could ever be an expression of love.

Throughout the film, the presence of childhood, whether in pictures, voice, story, or reflection, forces us adults to rethink our responsibility, imagination, apocalyptic terrors and the formation of our own memories. The title section itself, proposes science fiction as a species of film haunted by science, obsessed with death and always about catastrophe. With visuals weaving together Riefenstahl, Terminator and many more familiar images, it leaves us with the challenge of how we will invent the future. —Ken Anderlini, Vancouver International Film Festival, 2003

Back to top

Date: 2 November 2003 | Season: London Film Festival 2003 | Tags: London Film Festival

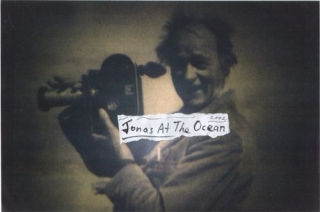

JONAS AT THE OCEAN

Sunday 2 November 2003, at 2pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

‘Jonas Mekas and his friends of free film, art and music.

A documentarypsychomusicfilm by Peter Sempel’

Peter Sempel, Jonas at the Ocean, Germany, 2002, 93 min

Together with his brother Adolphas, Jonas Mekas left Lithuania during World War II and eventually travelled to America as a ‘displaced person’. After settling in New York, he soon purchased a movie camera and began documenting the lives of Lithuanian immigrants. Within a few years, he was to become a central figure in the movement toward the recognition of film as art. The brothers’ arrival in New York (1949) is the film’s point of departure, and readings from ‘I Had Nowhere to Go’, Jonas’ autobiography of the period, appear throughout. Sempel loosely traces Mekas’ post-war life, as told through his interactions with other members of the arts community. There are visits with Robert Frank, Merce Cunningham and Nam June Paik, and with La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela in their ‘Dream House’. Allen Ginsberg tells the story of Pull My Daisy and the birth of beat cinema, while Phillip Glass speaks of Jonas’ independent sprit and the beginnings of the downtown arts scene in the 60s. Sempel borrows liberally from Mekas’ own films, while offering us glimpses of a life which we are more often used to seeing from his own point of view looking out.

PROGRAMME NOTES

JONAS AT THE OCEAN

Sunday 2 November 2003, at 2pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

JONAS AT THE OCEAN

Peter Sempel, Germany, 2002, 16mm, colour, sound, 93 min

It’s actually a prolongation of Jonas In The Desert, so Part Two, but with less talking and more music. I think , feel with music you can come nearer to something , someone than with any words (of course there are also interviews, for example with Jonas, Robert Frank, Nam June Paik, Phil Glass…) I’ve been filming Jonas (not shown at all in Part One) and also new scenes as I kept on filming after 1994, actually ’til, 2001. It starts with Jonas at the seashore in Lithuania laughing and filming children and running into the water with his Bolex camera, with ‘Starlight’ by Lou Reed and John Cale (about Warhol films), his hat flies away in the wind … He reads from his book, about the days in Germany … A wonderful scene where he repeats the landing at the Hudson with Algis and his brother Adolphas (filmed in slow motion – Jonas Scholz, the cameraman did a great job!) … Him running through the wide fields of his home country, chasing cows, hugging a white horse, and running to the horizon and back into the camera … Of course also in New York, and Torino, Barcelona, Paris, Berlin, Hamburg, Sao Paulo, Washington, Montauk and … and …

Some highlights: Robert Frank in his studio, talking about the old days, a ‘light show’ with La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela, Nick Cave reads from ‘I Had Nowhere To Go’ (the scene with the peepshow in the 1950s, 42nd Street, it’s beautiful and sad. Nick reads in his little green backyard house in London, dramatically (black + white, 16mm), it’s great.) … More guests: Rudy Burkhardt talking wildly about Maya Deren, Allen Ginsberg, Julius Ziz, Kenneth Anger, Tony Conrad (with a great performance in Buffalo), Stan Brakhage, Vincent Canby, Raimund Abraham, Peter Kubelka, Michael Snow, Fernando Arrabal, Zoe Lund and Harvey Keitel, Wim Wenders (calling Jonas the James Joyce of film art …), Blixa sings a song, Kiki and more … Jonas doing an Artaud performance on the Anthology-stage, at the top of his voice … Really quite crazy he is sometimes, how wonderful! Music: from underground, classical to Lithuanian folksongs. Okay, this could give you a little idea. The whole film is 93min on 16mm. —Peter Sempel

Back to top

Date: 2 November 2003 | Season: London Film Festival 2003 | Tags: London Film Festival

THE ILLUSION OF MOVEMENT

Sunday 2 November 2003, at 4pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

John Smith, Worst Case Scenario, UK, 2003, 18 min

This new work by John Smith looks down onto a busy Viennese intersection and a corner bakery. Constructed from hundreds of still images, it presents situations in a stilted motion, often with sinister undertones. Through this technique we’re made aware of our intrinsic capacity for creating continuity, and fragments of narrative, from potentially (no doubt actually) unconnected events.

Michele Smith, Like All Bad Men He Looks Attractive, USA, 2003, 23 min

Michele Smith, They Say, USA, 2003, 49 min

Michele Smith creates intense, hand-made collage films from a diverse assortment of film materials, mixing formats and contents with spontaneous regularity. Using a heavily re-edited 16 or 35mm film as a base, she manually weaves in other film footage, plastic shopping bags, translucent products, slides and other materials to create a master reel that is impossible to duplicate. Being too unwieldy to pass through a laboratory printer, the work must ultimately be shown on video, with the transfer done intuitively by hand, shooting frame-by-frame with a digital camera. Unlike, 2002’s Regarding Penelope’s Wake, these two new interchangeable pieces also contain digitally interwoven found video footage. They are truly amorphous time-based sculptures whose barrage of visual stimulus leave themselves wide open to personal interpretation. This is original and challenging work, demanding of its audience, and rewarding in its illumination.

‘I want my films to be open. The viewer creates the version of the film they will see by the way in which they view it. This is on a narrative, symbolic, metaphorical level as well as on a visual and structural level. The rapid intercutting and weaving of strands of different footage and elements creates a time space where one must mix what they are seeing for themselves. There is no way to perceive the links of still images into an illusion of movement. One can, with a readjusting of their viewing, change their experience of the work throughout.’ (Michele Smith)

PROGRAMME NOTES

THE ILLUSION OF MOVEMENT

Sunday 2 November 2003, at 4pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

WORST CASE SCENARIO

John Smith, UK, 2003, video, colour, sound, 18 min

For his latest work, Worst Case Scenario, Smith took four thousand still photographs of daily life on a Viennese street corner. The film re-orders and manipulates a selection of these images, and as it progresses the static world slowly and subtly comes to life. As Sigmund Freud casts his long shadow across the city, an increasingly improbable chain of events and relationships starts to emerge. —Open Eye Gallery

LIKE ALL BAD MEN HE LOOKS ATTRACTIVE

Michele Smith, USA, 2003, video, colour, silent, 23 min

THEY SAY

Michele Smith, USA, 2003, video, colour, silent, 49 min

This new work consists of one film split into two parts. Two parts which can be seen in either order, or separately if one so chooses.

In Like All Bad Men He Looks Attractive the mixed mediums are woven together on Mini DV. The materials are one reel of 35mm film and two reels of 16mm film. Inset into the 35mm film are plastic shopping bags, translucent plastic folders and plates, Mylar drafts used as blueprints for bridge construction, Viewmaster slides, paparazzi slides found at a tourist memorabilia shop on Hollywood Boulevard (including Zsa Zsa Gabor, Charlton Heston and George Peppard with a big white rabbit), slides purchased in the gift shops at the Getty Museum and at Hearst Castle, “sign here” tabs from my accountant, the wings of a dying butterfly that I tried to rescue from the hot pavement of a grocery store parking lot, Hollywood movie trailers, 8mm home movies and stag films, 16mm footage (including an episode of Green Acres), Viewmaster stills from 1970s TV shows, etc. Some things were not inset into the reel but recorded in the same manner and later cut in digitally. Panels, or film ‘carpets’: large mats made of 16mm film. Old magic lantern slides. The base film the elements are physically cut into is a workprint of raw footage of an unknown actor with a bandaged finger standing in front of the camera. He occasionally raises an envelope and reacts to a clapboard. I received this reel of film from a friend who’s a bit of a packrat (like myself). Before I met him, his house had burned down and this reel was one of the few items which survived. The decayed parts are where the emulsion melted from the heat.

The digital transfer was hand shot frame by frame against a crafter’s lightboard with a 25 watt candelabra bulb because the plastic folders and other elements inset into the 35mm would not go through the telecine transfer machine. I decided not to set an exact frameline and moved the filmstrip casually past the camera. This process added a feeling of the material celluloid form bending and moving as fast stills in time, with light reflecting through and glaring against it. I shot each frame as a still – which then had to be loaded into the Mac and sped up. It’s approximately equal to 10 frames per second, film speed. I alter this rhythm at different points in the film. There is also a cheesy faux-shutter effect for the still shots which was built into the camera I used – it becomes a chaotic and erratic half-flicker when sped up.

Intercut into this are found VHS tapes I bought with my grandmother at the local Greek deli and produce shop. They were getting rid of their rental videos and for some reason I must have looked like someone who would buy the entire shopping cart full because the shopkeeper made a deal and offered all of them to me. I used footage from four of these films in sections during both films. While watching these tapes I decided this material would be an interesting element to add to my film. Much of it is cut at an interval of three digital frames (which is about 30 frames per second) after every 12 frames of transferred film. A friend did this while I sat by and watched and told him where to split the images because I was at that point not too keen on editing digitally and did not know how it would turn out. Regarding Penelope’s Wake was pure in its filmic structure. The only digital editing done to that film was to clean up between reel changes and breaks in the film during transfer. By the end of the digital interweaving edits in the new films, I jumped in and did it myself and reworked some rhythm structures. As the work progressed, I became quite pleased with the possibilities and interactions of this new set of elements, and with the subtle contrasts and interactions of different mediums, times, and textures.

They Say consists of two reels of heavily edited (frame by frame) and overlaid 16mm film. It was then intercut with the grainy and scratchy melodrama rental tapes. I used a few 16mm found footage source reels as the main focus to play with narrative structure in a way related to but different than in my first work. I used a lot of footage from one narrative short film about a boy and a wild horse. When nearing the end I tired of editing it and decided to put it out into my garden and then dumped a few litter boxes on top. Contents: wood pellets and bunny poop. I forgot how long I left it outside … it rained a few times. Perhaps a week. It was later washed with laundry detergent and hot water.

I want my films to be open. The viewer creates the version of the film they will see by the way in which they view it. This is on a narrative , symbolic , metaphorical level as well as on a visual and structural level. The rapid intercutting and weaving of strands of different footage and elements creates a time space where one must mix what they are seeing for themselves. There is no one way to perceive the links of still images into an illusion of movement. One can, with a readjusting of their viewing, change their experience of the work throughout. —Michele Smith

Back to top

Date: 2 November 2003 | Season: London Film Festival 2003 | Tags: London Film Festival

FILM AS A SUBVERSIVE ART

Sunday 2 November 2003, at 7pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

Paul Cronin, Film as a Subversive Art: Amos Vogel and Cinema 16, UK, 2003, 56 min

Speaking recently about the myriad dangers facing humanity, director-provocateur Werner Herzog cited ‘the lack of adequate imagery’ as one of the most troubling. It’s a view Amos Vogel would surely endorse. As one of America’s most important curators, historians and festival directors, his influence on artists, experimental and underground film cannot be overstated. Born in Austria in 1922 but resident in New York since 1938, Vogel created the path-breaking film society Cinema 16 in 1947, introducing a continent to previously unseen worlds of experience. 20 years on, he established the New York Film Festival and with his eye-changing book ‘Film as a Subversive Art’, penned a revolutionary analysis of the moving image. Now, in Cronin’s valuable tribute to an extraordinary man and his times, Vogel delivers a series of compelling and entertaining reflections on a life lived in the passionate belief that film has a fundamental, radical and ethical role to play in society. Required viewing for anyone who believes cinema matters. Really matters. (Gareth Evans)

followed by

Exhibitionism: Subversive Cinema and Social Change

Following the screening of Film As A Subversive Art: Amos Vogel and Cinema 16 we will be staging a panel discussion focusing on some of the key issues raised in the film.

PROGRAMME NOTES

FILM AS A SUBVERSIVE ART

Sunday 2 November 2003, at 7pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

FILM AS A SUBVERSIVE ART: AMOS VOGEL AND CINEMA 16

Paul Cronin, UK, 2003, video, colour, sound, 56m

An hour-long profile of Amos Vogel, 82-year old New York resident and Austrian emigré, founder of the New York Film Festival and the Cinema 16 film society.

In 1947, Amos Vogel established a film club in New York called Cinema 16, the most important and influential film society in American history. At its height it boasted thousands of members, inspired a nationwide network of smaller film societies, and gave birth to the very rich tradition of post-war film culture that still exists in the United States. More than a decade before the father of modern ‘independent’ cinema – John Cassavetes – even picked up a camera, Vogel was bringing to a mass audience new ways of looking at world cinema.

The audiences of Cinema 16 were presented with a wide range of film forms, often programmed so as to confront – and sometimes to shock – conventional expectations, including works of the avant-garde, documentaries of all kinds, experimental animation, and foreign or independent features and shorts not in distribution in the United States. From the very beginning Vogel was determined to demonstrate that there was an alternative to industry-made cinema. Initially concentrating on non-fiction, he became the first programmer to show the works of Polanski, Cassavetes, De Palma, Kluge, Oshima, Ozu, Polanski, Rivette and Resnais (among many others) to American audiences. Vogel saw himself as a special breed of educator, using an exploration of cinema history and current practice not only to develop a more complete sense of the myriad experiences film culture had to offer, but also to invigorate the potential of citizenship in a democracy, and cultivate a sense of global responsibility.

Film as a Subversive Art: Amos Vogel and Cinema 16 tells the story of Cinema 16 through a vivid compilation of images and sounds, including a selection of newly filmed interviews with Amos Vogel (erudite and charismatic on-camera) and historian Scott MacDonald, author of a recent book about Vogel and Cinema 16. Vogel is filmed in various New York locations that are pertinent to the history of Cinema 16 and to New York film culture in general. There are rostrum shots of some of the photographs and beautifully designed catalogues and leaflets from Vogel’s extensive Cinema 16 archive. The film also contains excerpts from a selection of films screened at Cinema 16 between 1947 and 1963, including Roman Polanski’s Two Men and a Wardrobe, the infamous Nazi propaganda film The Eternal Jew, and the only film made by legendary New York press photographer Weegee. —Paul Cronin

Back to top

Date: 2 November 2003 | Season: London Film Festival 2003 | Tags: London Film Festival

UNKNOWN PARTS OF THE WORLD

Sunday 2 November 2003, at 9pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

Thomas Comerford, Figures in the Landscape, USA, 2002, 11 min

Grainy, undefined images shot with a pinhole camera accompany recitations of texts tracing the history of suburban housing from the rudimentary dwellings of Native Americans and the early settlers. An inquiry into human interaction with the landscape and notions of land development.

David Gatten, Secret History of the Dividing Line, USA, 2002, 20 min

Text-based, hand-processed treatment of Colonel William Byrd II’s 1728 expedition to settle disputes on the boundary between two American states, as chronicled in his ‘Histories of the Dividing Line Betwixt Virginia and North Carolina’.

Ben Russell, Terra Incognita, USA, 2002, 10 min

‘A lenseless film, whose cloudy images produce a memory of history. Ancient and modern explorer’s texts on Easter Island are garbled together by a computer narrator, resulting in a forever repeating narrative of discovery, colonialism, loss and departure.’

Phil Solomon, Psalm III: Night of the Meek, USA, 2002, 23 min

Obscure, ghostly faces emerge from a degraded, murky image, not through animation, but chemical and optical treatments of re-photographed and original material. A transcendental nightmare vision based on the legend of the golem. ‘A Kindertotenlieder in black and silver, on a night of gods and monsters.’

Naoyuki Tsuji, A Feather Stare at the Dark, Japan, 2003, 17 min

Pencil animation telling the mystical pre-history of the world through surreal, transformational drawings which depict the struggle between good and evil at the origins of evolution.

PROGRAMME NOTES

UNKNOWN PARTS OF THE WORLD

Sunday 2 November 2003, at 9pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

FIGURES IN THE LANDSCAPE

Thomas Comerford, USA, 2002, 16mm, colour, sound, 11 min

In making films with a pinhole camera, returning to a technology that predates the invention of cinema, Thomas Comerford uses consciously archaic means to comment on cinema’s technology and on technological progress in general. The fragile, fuzzy images that result from the replacement of the camera lens by a tiny hole have a wispy, almost virtual quality that refers back to the camera obscura of the Renaissance. Figures in the Landscape, set in Schaumburg, one of the Chicago area’s more sprawling suburbs, includes town maps and plans as well as images of people standing amid empty, almost soul-less spaces. Comerford uses found texts to describe the nature of suburban development and the way high-tech homes have replaced the more ‘primitive’ dwellings of Indians and early European pioneers, thus comparing his pinhole technique with early residents’ primitive homes on the one hand while the slicker and higher-tech cinema which he eschews is implicitly paralleled to the new homes of Schaumburg on the other. Comerford’s ironic point about ‘progress’ is reinforced when we hear about the Indians’ use of trees as trail markers while seeing a giant pole, and hear about early pioneer homes while seeing a particularly vulgar oversized modern dwelling. —Fred Camper

SECRET HISTORY OF THE DIVIDING LINE

David Gatten, USA, 2002, 16mm, b/w, silent, 20 min

When using tape to make a splice the cut pieces of film are placed end to end and the tape itself covers the gap: it is a band-aid and a bridge. But as the splice ages a line becomes visible; eventually the adhesive dries and the connection dissolves. When making a cement splice, there is more violence involved. The films are not placed end to end but instead are crushed into one another. Frames are lost, emulsions are scraped. But the well made splice is strong: in fact, it is permanent. Unlike tape, there is no going back. And it leaves a mark – a line – covering a third of one of the frames. A splice marks difference and defines duration. To suppress that mark is to pretend that we will live forever. Instead, take your splicer and knock the blade out of alignment. Forego the B-roll in favour of a single strand of faith. Hold your breath and count the hours since you were last together. Blow softly on a wet face and watch the smile form. Float your hand across the surface and find all the words you need. Unfold the splicer and separate your image from your dream; you will feel bound, as if tied down until you are fully awake. Only then will you know for sure: this may not be final but it is definite. The landscape you see can change only when you pass through it. Regard your new object: a union: silent, tiny and bright. Paired texts as duelling histories; a journey imagined and remembered; 57 mileage markers produce an equal number of prospects. The latest in a series of films about the division of landscapes, objects, people, ideas and the Byrd family of Virginia during the early 18th century. —David Gatten

TERRA INCOGNITA

Ben Russell, USA, 2002, 16mm, colour, sound, 10 min

In the in-between of history and memory lies the Unknown Part of the World. I have seen it, however briefly – projected out in front of my eyes like some old-timey silent film. I knew the place immediately, what with its rusted factories , fallen statues , floating figurines, but the image was lost as soon as the reel ran out. Played it back. Mapped out the sounds. Grabbed a camera, a makeshift recording device, played it back. And again. Each time I cobbled together a newer world, cut and spliced out of words and images from this one; but they seem to accumulate, these geographies – each one charted proposes an entirely different set of islands , continents , planets moving about just beyond the horizon. Therein lies the joy and terror; and throughout all of it, this camera here is but a minor tool in sifting through this shifting terrain. —Ben Russell

PSALM III: NIGHT OF THE MEEK

Phil Solomon, USA, 2002, 16mm, b/w, sound, 23 min

It is Berlin, November 9, 1938, and, as the night air is shattered throughout the city, the Rabbi of Prague is summoned from a dark slumber, called upon once again to invoke the magic letters from the Great Biij that will bring his creatures made from earth back to life, in the hour of need. A Kindertotenlieder in black and silver, on a night of gods and monsters …

In Germany, Before the War:

I’m looking at the river,

but I’m thinking of the sea,

thinking of the sea,

thinking of the sea …

I’m looking at the river,

but I’m thinking of the sea,

thinking of the sea,

thinking of the sea … —Phil Solomon

A FEATHER STARE AT THE DARK

Naoyuki Tsuji, Japan, 2003, 16mm, b/w, sound, 17 min

This is the tale in the pre-world before bearing our earth. There is the world in chaos with the existence of the force of the good and evil that has interfered with each other. And it is going to build the chance of birth in the New World. The pre-world is carrying out a growth expansion at the same time, going to decay. However, the force of the decay sets up birth in the coming world. —Naoyuki Tsuji

Back to top