Sonic Celluloid

Date: 21 March 1999 | Season: Seasons | Tags: Tony Conrad

SONIC CELLULOID

Sunday 21 March 1999, at 10:30pm

London ICA Theatre

An evening of music & film from the lofts of New York presented by Mark Webber & Robert Worby as part of the Sonic Arts Network’s Cut & Splice Festival 1999.

A programme of electroacoustic music will be accompanied by screenings of:

Ira Cohen, The Invasion Of Thunderbolt Pagoda, 1968, 31 min

Tony Conrad & Beverly Grant Conrad, Coming Attractions, 1970, 77 min

THE INVASION OF THUNDERBOLT PAGODA

Ira Cohen, USA, 1968, 16mm on VHS, colour, sound, 31 min

Directed and Produced by Ira Cohen. Photographed By Bill Devore. Tony Conrad, Sheldon & Diane Rochlin. Edited By Ira Cohen & Marty Topp. Costumes & Make-up Under the Supervision of Robert Lavigne. Music By Angus & Hetty Maclise, Loren Standlee, Ziska, Raja Samyana, Tony Conrad, Jackson MacLow, Henry Flynt. Starring The Universal Mutant Repertory Company With Rosalind, Robert Lavigne, Hakim Khan, Pedro Arbol De Pera, Fan Fan Sheba, Hetty Maclise, Angus Maclise, Beverly Grant, Tony Conrad, Robert Richkin, Erin Matson, Martha Muse, Kip Coburn, Loren Standlee, Ziska, Kirkwood, Bill Reynolds, David Gurin, Nina, Fritz Mooney, Donna Alnutt, Micah. Made with the help of Josh Reynolds and the International Audio Visual Institute.

“From The Secret Museum, a film of Ritual Magic conceived in three parts: The Opium Dream, Shaman & Heavenly Blue Mylar Pavilions. A Spiritual Voyage through the unconscious by way of alchemical dream exorcism & celestial rebirth.” (Ira Cohen)

The poet and shaman Ira Cohen was the originator of mylar photography and the only artist to use this technique to build up a substantial body of work. With The Invasion Of Thunderbolt Pagada, Cohen sought to further investigate the mystical properties of mylar as used on moving images. This psychedelic ritual was originally planned to feature underground legend Jack Smith, who resigned from the project over a minor misunderstanding about a cat. Cohen still regards the film as unfinished since he rushed to complete it in time to premiere at New York University alongside Paradise Now (the film of the Living Theatre’s controversial production) and Jud Yalkut’s Aquarian Rushes. Ira Cohen is one of the few survivors of the beat generation, a prolific poet who has recently completed Kings With Straw Mats, a documentary video of the 1986 Kumbh Mela festival of mystics in Hardwar, India. The soundtrack of Invasion consists of recordings of two collective improvisations led by poet and hand drummer Angus MacLise, who is best remembered today for his involvement with the Velvet Underground. MacLise accompanied many multimedia performances, composed the soundtrack to Ron Rice’s Chumlum, and was the drummer for La Monte Young’s Theatre if Eternal Music. In the 1970s he lived mostly in India and Nepal, where he died in 1979. Angus’ widow Hetty MacLise , who appears in the film and on the soundtrack, will introduce the film this evening.

(Ira Cohen’s new film Kings With Straw Mats will receive its British premiere at the October Gallery in London at 7:30pm on Tuesday 23rd March 1999.)

COMING ATTRACTIONS

Tony Conrad & Beverly Grant Conrad, 1970, 16mm, colour, sound, 77 min

Directed by Beverly Grant Conrad. Produced in Tantacolor by Tony Conrad. Starring Francis Francine as Mae, and featuring Joan Adler, Stanley Alboum, Tally Brown, Vincent Karas, Krash Kavanaugh, Frank Lilly, Baby Bettie Moses, Lewis and Rosanne Oliver, Sam Ridge, Ritty, Claude Purvis, Marie Antoinette Rogers, Arnold Rockwood, Amirom Rosson, Lohr Wilson, plus many others. Music by John Cale, Jim Boyd, Angel De Maria, Charlemagne Palestine, Terry Riley, La Monte Young. Lighting by Noah Lemy. Costumes By Betsey Johnson & The Cast. Titles By Peter Conrad. Based on a Story by Andrew Lamy. With special thanks to the Rockerfeller Foundation.

“Coming Attractions was undertaken with the unifying objective of exploring virgin areas of filmic entertainment. We hoped to capture a whole new range of expressive possibilities through bringing together aspects of film that are usually treated independently. Coming Attractions, as a semi-narrative film, fuses abstract technological developments in film with the use of film as a story-telling medium” (Tony & Beverly Conrad)

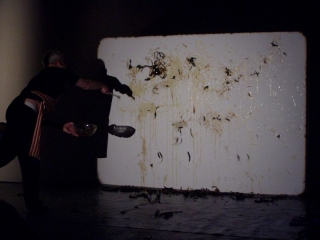

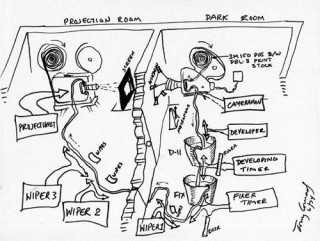

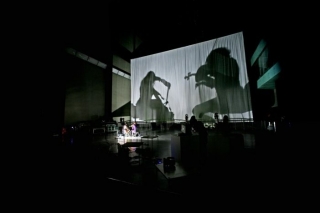

Up until his recent recognition as a musician, Tony Conrad was for many years regarded primarily as an avant-garde filmmaker. His 30 minute film The Flicker (1966) is thought of as the most effective and successful imageless film and consists solely of interchanging frequencies of black and white frames, which present different harmonic chords to the viewer and induce visual hallucinations. His introduction to the flicker effect was through improvised “filmless films” he developed with Jack Smith and Mario Montez – they were too poor to afford movie stock and acted live in the flicker of the projector beam. Tony Conrad’s introduction to the New York downtown scene was through his friendship with La Monte Young, in whose Theatre of Eternal Music Conrad played alongside Young, Marian Zazeela, Angus MacLise and John Cale. Beverly Conrad (née Beverly Grant) was a superstar of the underground movie scene, having appeared in films by Jack Smith, Andy Warhol and Gregory Markopoulos and stage productions at La Mama and the Theatre of the Ridiculous.

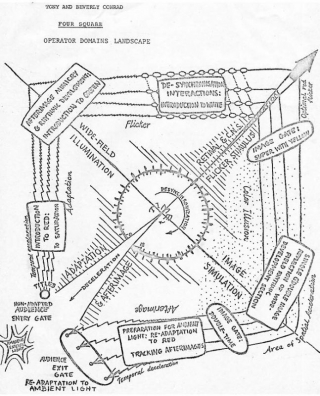

In 1968, Tony and Beverly Conrad decided to apply the flicker effect to a narrative story which was clearly influenced by the style of Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures. Francis Francine, a matronly transvestite, stars in the role of Mae, who is haunted by the memories of her life and loves. The story is told through languid set pieces, the soundtrack and visuals treated by a variety of effects and devices. The musical elements were culled from Tony Conrad’s archival recordings of friends and acquaintances and features composer La Monte Young singing a cowboy song, John Cale’s Coming Round Again and pieces by Terry Riley, Charlemagne Palestine and others. The film was completed in 1970 thanks to a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation. Tony and Beverly Conrad also collaborated on Straight and Narrow (1970) which astoundingly applies flicker to horizontal and vertical lines, with music by Cale and Riley.

(The Flicker by Tony Conrad will be shown at the National Film Theatre on Wednesday 31st March 1999 as part of the “Addendum” programme of avant-garde films chosen by Mark Webber.)

ELECTROACOUSTIC MUSIC, THE AMERICAN WAY

In the early 1950s composers began working with tape recorders – a major new invention that had been developing since the end of the Second World War. These were wild times that gave us rock ‘n’ roll, abstract expressionism and the jet engine. There was a great speeding- up of just about everything. As John Cage said, “What was so fascinating about tape was the possibility that a second, which we had always thought was a relatively short space of time, became 15 inches. It became something quite long that could be cut up.’’ Sound could be recorded and time became a precisely measurable piece of space. Just as film makers had done years earlier, composers could now cut, splice and reverse time. They could speed it up and slow it down. And when they did these things they uncovered amazing sound worlds, previously unheard. This was composing with all sounds, not just notes.

John Cage lays claim to being the first American composer of musique concrète – the technique of making music with recorded and manipulated sounds. His Imaginary Landscape No.5 (for any 42 recordings), was composed in 1951 and Williams Mix was composed in 1952. (The title refers to Paul Williams, a wealthy architect who funded the project.) This piece originally used 8 unsynchronised mono tapes of sounds divided into 6 categories: A) City Sounds; B) Country Sounds; C) Electronic Sounds; D) Manually Produced Sounds (including music); E) Wind Produced Sounds (including songs); F) “Small.’’ Sounds requiring amplification. The recordings were either used in their original state or varied in some way. The 6 categories and possibilities of variation or non-variation were subjected to chance operations using the l-Ching and a score was produced. The score was a template, a life-size drawing of the actual tape, and it worked like a dressmaker’s pattern showing all the cuts and splices that needed to be made to generate the piece. The construction was incredibly laborious and took Cage, and his friends Morton Feldman, Christian Wolf and Earle Brown, many months to complete. It was made in the studios of Louis and Bebe Barron who later became famous for their score of the seminal sci-fi film Forbidden Planet.

Perhaps the most well-known piece of tape music of all time is Revolution 9, from the Beatles’ White Album, composed by John Lennon and Yoko Ono. Many critics have mentioned the influence of Karlheinz Stockhausen or John Cage when referring to this piece but the greater influence is likely to be Richard Maxfield. In the early 1960s in Yoko Ono’s loft, in New York, the avant-garde gathered to witness many things, including the possibilities of the tape recorder. Here Richard Maxfield performed his tape works, some of which were made by the use of microphones and some with purely electronically generated sounds. Cough Music is made with the sounds of coughing taken from recordings of symphony concerts (Maxfield made a living for a while as an editor of classical records), Sine Music, Trinity Piece and Pastoral Symphony all use pure electronics. These electronic sounds were made with very simple circuits often built by Maxfield himself; he was the original lo-fi composer. His approach was typical of the pioneering American experimentalist, rejecting the techniques of the European avant-garde, which at that time were dominated by Karlheinz Stockhausen in the studios of the West German Radio in Cologne. One of Maxfield’s methods involved the recording of simple electronic waveforms onto tape and then building complex rhythms and gestures by cutting the material into short fragments which were then edited back together randomly; the very antithesis of the strict serial structures employed by Stockhausen.

Terry Riley’s piece The Gift was made for the play of the same title by Ken Dewey a director of experimental theatre and Happenings. It involves the manipulation of a recording of Riley’s arrangement of the Miles Davies piece So What, featuring Chet Baker playing trumpet. The piece was recorded in its entirety and then separate recordings were made of the trumpet, trombone and bass. All of this material was subjected to tape loop processes developed by Riley and an engineer at the ORTF studios in Paris where the piece was made. The modal nature of the recorded music allowed the construction of extended echo techniques without dissonant clashes. This is a classic ‘process’ piece where the structure unfolds audibly in a very straightforward way. The result is a kind of re-make of the work whereby melody and rhythm are slowly changed into colour and texture, and the listener is taken from the familiar into the unfamiliar. Interestingly this piece pre-dates the postmodern notion of appropriation and the now commonplace world of sampling and plunderphonics. (Robert Worby)