Date: 25 October 2008 | Season: London Film Festival 2008 | Tags: London Film Festival

ALINA RUDNITSKAYA

Saturday 25 October 2008, at 7pm

London BFI Southbank NFT3

Alina Rudnitskaya’s humanistic approach to documentary filmmaking often brings out the humour in her chosen subjects. As an introduction to her work, this programme depicts three diverse groups of contemporary Russian women.

Alina Rudnitskaya, Amazons, Russia, 2003, 20 min

A sensitive portrait of an unusual urban phenomenon: a troupe of independent and strong-minded girls who keep horses in the heart of St Petersburg. Amazons follows a new volunteer as she tries to find her place within the group dynamic.

Alina Rudnitskaya, Besame Mucho, Russia, 2006, 27 min

With music providing an escape from their duties as veterinarians, nurses and cleaners, the amateur chorus of a provincial town rehearse songs from Verdi’s ‘Aida’. Close bonds are formed, but in true diva style, relationships within the choir are frequently inharmonious.

Alina Rudnitskaya, Bitch Academy, Russia, 2008, 29 min

An improbable symbol of modern Russia is displayed in this tragicomic verité on the aspirations of young women. In a progressive twist on assertiveness training, a middle-aged, paunchy Casanova (who surely loves his job) gives classes on how to seduce the male using role play, styling critiques and sexy dancing. The ultimate goal is to hitch a millionaire, and though there’s much humour in the situation, occasional tears and telling looks remind us that the insecurities of real lives are being laid bare.

PROGRAMME NOTES

ALINA RUDNITSKAYA

Saturday 25 October 2008, at 7pm

London BFI Southbank NFT3

AMAZONS

Alina Rudnitskaya, Russia 2003, 35mm, colour, sound, 20 min

A cinematic portrait of a strange urban phenomenon: female equestrians who make a living by riding horses in the city streets and dogmatically oppose the participation of men. The inside story of these urban Amazons is shown through the eyes of a rookie team member. (Shadow Festival, Amsterdam)

BESAME MUCHO

Alina Rudnitskaya, Russia, 2006, video, colour, sound, 27 min

An amateur women’s choir in the provincial Russian town Tikhvin rehearses the opera ‘Aida’. In the daytime these women – heroes of the film – have ordinary life, work in the shops, remove the garbage, load goods on trucks, overcome the illnesses, but in the evenings they are carried away in absolutely different world. Their lives are filled with dreams, expectations of something bigger, brighter, that will help them to fly away from their ordinary life that is hard sometimes. The brief visit of the Italian delegation for which they rehearsed the opera underlines their illusions. The film is full with sadness and humour, which is true to the atmosphere of Russian village life in these times. (St. Petersburg Documentary Film Studio)

BITCH ACADEMY

Alina Rudnitskaya, Russia, 2008, video, colour, sound, 29 min

There were times, when ‘bitch’ had a negative connotation, but today it has become a real brand. ‘Bitch’ has become an example to follow for modern woman, an ideal image of our days. Most women older than 15 try to learn how to be a bitch. Who is a vixen, a modern bitch? How to become successful women? What does it mean to be a woman? What is ‘women’s nature’ and ‘women’s spirit’? Is it possible for a women to achieve, to succeed in this life without crossing ethical borders? A vixen is not a hysterical woman or capricious fool or envious snake. A vixen is a woman that follows her own desires but not someone’s advice, she is independent and relies on herself only, she knows what she wants from life and men, she doesn’t follow common stereotypes, she knows men’s ‘weak’ points, and what is more – she has her inner freedom. The main shooting technique used in this film is a method of observation. Over time, the camera didn’t attract attention to itself, leaving the subjects comfortable and behaving in a natural way. This film pretends to be called ‘the best documentary comedy’ about women. (St. Petersburg Documentary Film Studio)

Back to top

Date: 25 October 2008 | Season: London Film Festival 2008 | Tags: London Film Festival

WHEN LATITUDES BECOME FORM

Saturday 25 October 2008, at 9pm

London BFI Southbank NFT3

Francisca Duran, In the Kingdom of Shadows, Canada, 2006, 6 min

Set in metal type, a passage from Maxim Gorky’s review of the Lumières melts into a pool of molten lead.

David Gatten, How to Conduct a Love Affair, USA, 2007, 8 min

‘An unexpected letter leads to an unanticipated encounter and an extravagant gift. Some windows open easily; other shadows remain locked rooms.’ (David Gatten)

Charlotte Pryce, The Parable of the Tulip Painter and the Fly, USA, 2008, 4 min

A saturated cine-miniature inspired by Dutch 17th Century painting.

Sami van Ingen, Deep Six, Finland, 2007, 7 min

The film image of a loaded truck, careening free of its position in the frame, speeds along a mountain road towards an inevitable fate.

Bart Vegter, De Tijd, Netherlands, 2008, 9 min

Computer animated abstraction in three dimensions. Slowly evolving geometric forms suggest sculptural figures and waning shadows.

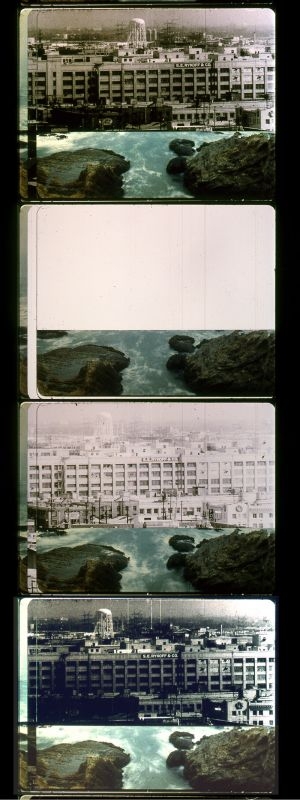

Pat O’Neill, Horizontal Boundaries, USA, 2008, 23 min

O’Neill’s dizzying deployment of the 35mm frame-line is intensified by Carl Stone’s electronic score. A hard and rhythmic work, thick with superimposition, contrary motion and volatile contrasts, reminiscent of his pioneering abstract work of prior decades.

Bruce Conner, Easter Morning, USA, 2008, 10 min

Conner’s freewheeling camera chases morning light in a hypnotic blur of colour and multiple exposures. This final work by the artist and filmmaker rejuvinates his rarely seen 8mm film Easter Morning Raga (1966). With music by Terry Riley.

PROGRAMME NOTES

WHEN LATITUDES BECOME FORM

Saturday 25 October 2008, at 9pm

London BFI Southbank NFT3

IN THE KINGDOM OF SHADOWS

Francisca Duran, Canada 2006, video, b/w, sound, 6 min

In the Kingdom of Shadows documents a paragraph being typeset on an early twentieth-century Ludlow Linecaster. The text is taken from Maxim Gorky’s 1896 review of the Lumière Brothers’ film L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de la Ciotat (1895). As the words melt into a pool of lead, the alchemical magic of printing is linked to that of cinema. Commissioned by the Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto (LIFT) for their 25th anniversary program, ‘Film is Dead! Long Live Film!’ (Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre)

HOW TO CONDUCT A LOVE AFFAIR

David Gatten, USA, 2007, 16mm, b/w & colour, silent, 8 min

An unexpected letter leads to an unanticipated encounter and an extravagant gift. Some windows open easily; other shadows remain locked rooms. Advice is sometimes easy to give, but often hard to follow. Have a cup of tea dear. I’ll trade you a stitch from the past in return for a leaf from the future. This is a Valentine and this is a fragment: for the one who mends my rips; from the next instalment of the Byrd project Secret History of the Dividing Line, a True Account in Nine Parts. (David Gatten)

www.davidgattenfilm.com

THE PARABLE OF THE TULIP PAINTER AND THE FLY

Charlotte Pryce, USA, 2008, 16mm, colour, silent, 4 min

Inspired by Dutch paintings from the 17th century – as indeed are all my films – it features a tulip, the painting of a tulip and a fly. An intoxicating flower; a metaphorical insect; a longing reach across the centuries. The film is a philosophical search drenched in luminous colours and sparkling light, shot on colour reversal, entirely hand-processed and re-printed on the optical printer. (Charlotte Pryce)

DEEP SIX

Sami van Ingen, Finland, 2007, 35mm, colour, sound, 7 min

Deep Six has three starting points: a little narrative re-edited from a Hollywood B-movie (The Rage, 1998), an attempt to use the colour photocopy as a cinematic aesthetic and an exploration of the frame line as a dynamic visual element. The pictoral narrative in the work, a timber lorry racing on a mountain road, acts as a metaphor for change and of loss. In a wider sense the narrative also represents all traditional narrative structures, with the three compulsory parts: the Exposition, Rising Action and Climax. In Deep Six I strive to have the mechanical touch of my hand visible as a comment on the analogue nature of the medium – what we see depends on the condition of the lamp, the condition of the actual surface of the film print and of the projectionist’s ability to focus the film. The discrepancies in my images, made by contact printing, by hand, strips of photocopied overhead transparencies onto 35mm film, the strong frame line and sideways movement and the strong texture of the photocopied surface is an attempt to work the screen surface and the framing of the cinematic image. (Sami van Ingen)

DE TIJD

Bart Vegter, Netherlands, 2008, 35mm, colour, silent, 9 min

For almost thirty years now, Bart Vegter has been making abstract animations. His first four films were exquisitely minimal geometric compositions made using a variety of traditional animation techniques. The last fifteen years Bart Vegter has been making his films on the computer, writing his own software to explore the worlds of patterns hidden in complex mathematical algorithms. These patterns often evoke natural phenomena like the shapes of sand dunes or the weather. His most recent work De Tijd (Time) marks a return to a more geometrical world of forms. ‘A monochrome flat image changes slowly into a theatrical spectacle in which colour subtly melts and solidifies lines and conical forms. At the end, the colours lose their power and all that is left is the basic structure of the image, the skeleton.’ This is the second work by Vegter that uses Fourier transformation, this time in three dimensions. (Joost Rekveld)

HORIZONTAL BOUNDARIES

Pat O’Neill, USA, 2008, 35mm, colour, sound, 23 min

Horizontal Boundaries is a film that looks at certain aspects of the geography of California as the ground for cinematic disruption and restatement. The ‘boundaries’ in question turn out to be frame lines, the divisions between two images, one above the other on a strip of 35mm film. The projector gate is adjustable up or down in order to produce a single uninterrupted image: in this film the frame line is integrated into the compositional language of the piece. It is not a static repositioning, but rather a dynamic one, moving more or less randomly, causing image combinations to be generated unpredictably. The result is a tapestry of exquisite contradiction. Irish traditional songs ‘Carranroe’ and ‘Out on the Ocean’, performed by George Lockwood, fiddle. A portion of a composition ‘Nak Won’, by Carl Stone. Language on the track was edited from two 1955 radio shows, ‘Dragnet’ featuring Jack Webb. Other original sound sources, and mix, by George Lockwood. (Pat O’Neill)

EASTER MORNING

Bruce Conner, USA, 2008, video, colour, sound, 10 min

This is Bruce Conner’s last completed film. It is derived from the 8mm footage of Easter Morning Raga (1966). Conner originally showed Easter Morning Raga projecting at variable frame rates and with loops, some prints were made but the film was never released for circulation. Easter Morning revisits the earlier material resetting it to a version of Terry Riley’s landmark minimalist composition ‘In C’ (1964) recorded by the Shanghai Film Orchestra in 1989. The use of traditional Chinese instruments in this unusual recording gives the music a shift in timbre that is revelatory, beautifully matching the radiance and open heartedness of this mind manifesting optical poem. (Mark McElhatten, New York Film Festival Views From the Avant-Garde)

Back to top

Date: 26 October 2008 | Season: London Film Festival 2008 | Tags: London Film Festival

KEMPINSKI

Sunday 26 October 2008, 12-7pm

London BFI Southbank Studio

Neil Beloufa, Kempinski, Mali-France, 2007, 14 min (continuous loop)

Whilst challenging our stereotypical view of Africa, Kempinksi also blurs the lines between documentary, ethnography and science fiction. Asked to imagine the future but to speak in the present tense, the protagonists describe extraordinary and unexpected visions.

PROGRAMME NOTES

KEMPINSKI

Sunday 26 October 2008, 12-7pm

London BFI Southbank Studio

KEMPINSKI

Neil Beloufa, Mali-France, 2007, video, colour, sound, 14 min

Kempinski is a mystical and animist place. People emerge from the dark, holding fluorescent lamps; they speak about a magical world. ‘Today we have a space station. We will launch space ships and a few satellites soon that will allow us to have much more information about the other stations and other stars.’ Their testimonies spark confusion and contradiction: a second reading is necessary to fully understand what is going on in this unique blend of fiction (sci-fi) and ‘real’ documentary. The scenario of Kempinski, filmed in various towns in Mali, is defined by specific rules: interviewed people imagine the future and speak about it in the present tense. Their hopeful, poetic and spiritual stories and fantasies are recorded and edited in a melodic way; Kempinski thus cleverly challenges our exotic expectations and stereotypes about Africa. (Montevideo)

Algerian and French, Neil Beloufa was born 1985 in Paris. He studied at the École des Beaux Arts de Paris (ensba), at the Art Décoratifs de Paris (ensad), at Cooper Union in New York and at CalArts in Valencia. Beloufa’s work has been exhibited and screened at ITCA 2008, the Prague International Triennial of Contemporary Art; 12th Biennial of Moving image, Geneva; Palais de Tokyo, Paris; White Box, New York; The Soap Factory, Minneapolis, and the NCCA (National Center of Contemporary Arts), Moscow. Kempinski was awarded the Arte Prize for European Short Film at the 54th Internationale Kurzfilmtage Oberhausen.

Back to top

Date: 26 October 2008 | Season: London Film Festival 2008 | Tags: London Film Festival

NATHANIEL DORSKY

Sunday 26 October 2008, at 2pm

London BFI Southbank NFT3

In his search for a ‘polyvalent’ mode of filmmaking, Nathaniel Dorsky has developed a filmic language which is intrinsic and unique to the medium, and expressive of human emotion. Seeking wonder not only in nature but in the everyday interaction between people in the metropolitan environment, Dorsky observes the world around him. Free of narrative or theme, his films transcend daily reality and open a space for introspective thought. ‘Delicately shifting the weight and solidity of the images’, a deeper sense of being is manifest in the interplay between film grain and natural light. Dorsky returns to London to introduce two brand new films and Triste, the work that first intimated his sublime and distinctive ‘devotional cinema’. These lyric films are humble offerings which unassumingly blossom on the screen, illuminating a path for vision.

Nathaniel Dorsky, Winter, USA, 2007, 19 min

‘San Francisco’s winter is a season unto itself. Fleeting, rain-soaked, verdant, a brief period of shadows and renewal.’ (Nathaniel Dorsky)

Nathaniel Dorsky, Sarabande, USA, 2008, 15 min

‘Dark and stately is the warm, graceful tenderness of the sarabande.’ (Nathaniel Dorsky)

Nathaniel Dorsky, Triste, USA, 1978-96, 19 min

‘The ‘sadness’ referred to in the title is more the struggle of the film itself to become a film as such, rather than some pervasive mood.’ (Nathaniel Dorsky)

PROGRAMME NOTES

NATHANIEL DORSKY

Sunday 26 October 2008, at 2pm

London BFI Southbank NFT3

Those familiar with Dorsky’s four-decade œuvre will appreciate that while his work stems from reality, it also partakes in a deeper, more wondrous realm – one that transcends words and physicality with remarkable grace. One of the most gifted 16mm filmmakers of our time, Dorsky is known for camera work that is precise and insightful, guiding us with a vision of the world that is electrified by its possibilities. His films are both silent and projected at silent speed, allowing for what he terms an unimpeded experience of ‘the flickering threshold of cinema’s illusion.’ His films offer visual symmetries, searing colour, and a sense of pure, unequivocal delight at celestial movement (Sarabande) and an earth-bound existence (Winter). (Andréa Picard, Toronto International Film Festival)

WINTER

Nathaniel Dorsky, USA, 2007, 16mm, colour, silent, 19 min

San Francisco’s winter is a season unto itself. Fleeting, rain-soaked, verdant, a brief period of shadows and renewal. (Nathaniel Dorsky)

SARABANDE

Nathaniel Dorsky, USA, 2008, 16mm, colour, silent, 15 min

Dark and stately is the warm, graceful tenderness of the sarabande. (Nathaniel Dorsky)

TRISTE

Nathaniel Dorsky, USA, 1978-96, 16mm, colour, silent, 19 min

Triste is an indication of the level of cinema language that I have been working towards. By delicately shifting the weight and solidity of the images, and bringing together subject matter not ordinarily associated, a deeper sense of impermanence and mystery can open. The images are as much pure-energy objects as representation of verbal understanding and the screen itself is transformed into a ‘speaking’ character. The ‘sadness’ referred to in the title is more the struggle of the film itself to become a film as such, rather than some pervasive mood. (Nathaniel Dorsky)

Back to top

Date: 26 October 2008 | Season: London Film Festival 2008 | Tags: London Film Festival

THE FEATURE

Sunday 26 October 2008, at 3:45pm

London BFI Southbank NFT3

Michel Auder & Andrew Neel, The Feature, USA, 2008, 177 min

In Michel Auder’s case, the truth is certainly stranger than fiction. One of the first to compulsively exploit the diaristic potential of the Sony Portapak, he was right there at the heart of the Warhol Factory and the Soho art explosion. This fictionalised biography draws on his vast archive of videotapes, connecting them by means of a distanced narration and new footage, shot by co-director Andrew Neel, in which Auder portrays his doppelganger, an arrogantly successful artist who may or may not have a life-threatening condition. Resisting nostalgia through wilful ambiguity, The Feature remains raw and brutally honest as Auder displays the best and worst of himself. Taking in his marriages to both Viva and Cindy Sherman, and affiliations with Larry Rivers, the Zanzibar group and the downtown art scene, this is necessarily a tale of epic proportions, chronicling an amazing journey through art and life whilst providing access to a wealth of fascinating personal footage.

Also Screening: Tuesday 29 October 2008, at 7pm, BFI Southbank Studio

PROGRAMME NOTES

THE FEATURE

Sunday 26 October 2008, at 3:45pm

London BFI Southbank NFT3

THE FEATURE

Michel Auder & Andrew Neel, USA, 2008, video, colour, sound, 177 min

Watching The Feature, vidéaste Michel Auder’s return to filmmaking (on HD video; co-directed by Andrew Neel, grandson of the late artist Alice Neel, Auder’s longtime friend and frequent subject), which premiered in the Forum at this year’s Berlinale, a sense of length becomes almost painfully pronounced, and not just because the film is long, which it is at 2 hours and 54 minutes (after the public screening, Auder announced it should be called ‘The Trailer’, and that the real film for him – the first cut – lasts more than eight hours). The overriding sense of summation that fidgets through the fictionalized auto-portrait likewise induces a squirmy viewing, though surprisingly, that’s a product of its strength, of its flashes of raw humanity cloaked in a narcissism too grand and too self-aware to be real.

Then again, what is real in this self-described ‘fictional biography?’ As the character of Michel Auder, our ruminative art star auto-portraitist, poking out from behind a rather ridiculous tondo of fruit and flowers, tells us, his image is to be judged ultimately by the culture that receives it (and sadly, very prematurely by the hordes who fled the Forum’s press screening within the first 15 minutes). His 5,000 hours of obsessively recorded and compiled video could be cut, censored, edited, and re-edited in countless ways – as could this article – portraying him as ‘a total asshole, a monster or a great poet.’ So how does he come off in The Feature? Obscenely vain, for one, and also profoundly lonely, charming at times and smart, despite his frequently inelegant English, which is not redeemed by his faded French accent. The tropes he plays out are ones belonging to a self-serving artist whose persona clings to a reality infused with the fictions of a fairytale. An unwonted fairytale, perhaps, but one that includes a fair dose of glamour, privilege and a certain renown – all of which combat rather voraciously against the mediocrity of a blanched, everyday existence. Even his intentionally unkempt haircut demonstrates this willing fight. And he knows it.

Auder is a handsome 63-year-old French man, who has been living in the US since the early ’70s. His wild life has been almost pathologically self-recorded since the late ’60s when he traded in his still camera and made his first feature film, Keeping Busy (1969). As a novice fashion photographer, the leap into filmmaking with the Zanzibar clan was not a colossal one. Auder borrowed Philippe Garrel’s 35mm camera, took Silvina Boissonnas’ generous production money and hit the road with Viva ‘Superstar’ and Louis Waldon, who had recently arrived in Paris with Nico, after having shot Warhol’s notorious Blue Movie (1969). Keeping Busy documents Viva and Waldon languidly not getting busy in various luxurious hotel rooms in Rome, recounting their Blue Movie escapades to an unknown Italian woman. Fact and fiction coalesced during production, and the film bears witness to Viva and Auder falling in love, the first of many personal experiences to be recorded by the artist. While the film exists as an exemplar of the Warhol-Zanzibar correspondence, Auder was more of a constellation figure, not really interested in pursuing a filmmaking career, though his path, one could argue, was just as ardent as and bears a number of similarities to that of Garrel, the sole (other) Zanzibar member still making feature films today. Auder obsessively makes video the way Garrel obsessively remakes Nico, and the two are former heroin addicts who have consistently made their addiction subjects of their work.

The discovery and purchase of the first-ever available Sony Portapak video camera was a major turning point in Auder’s life; since then, he has since chronicled his experiences and that of his friends with astonishing regularity, candour, and a seemingly boundary-less intimacy. The footage, much of which consists of or contributes in a recycled, resurrected or re-cut manner to his individual video works – some are available through Electronic Arts Intermix (and they are all listed at michelauder.com) – spares no one, especially not himself. Quite a bit different from conceptual video art, Auder’s works eschew phenomenological conceits; rather, they stem from the Warholian school of filmmaking, and have a rough-hewn home movie aesthetic and a thread of expiation coursing through them, at least from what is seen of the footage in The Feature. It’s no wonder that Jonas Mekas, the master poet of diaristic filmmaking, turns up for dinner and sings a little song. The two NYC émigrés seem close, part of the same circle of friends; one imagines that over the past 40 years they’ve likely both turned up at the same event or party with camera in hand. One assumes that the mediums and approaches, until recently, would have been quite different, one opting for a Super-8 lyricism based on engagement, the other for a digital form of art brut based on observation. Now they are both workingin video, and the tone has veered toward the nostalgic, toward an ending heretofore inconceivable. Watching recent Mekas films and The Feature, one is bound to ask why the present makes the past seem so urgent?

The Feature feigns many things, and attempts almost heroically to transcend its own truth (which is, after all, likely a form of non-truth), including the nostalgia inherent in its summative structure. Its pseudo-fiction saves the film from itself in a perverse kind of way. Looking back over one’s life, seeing it as ‘feature length,’ with all the good parts amounting to just shy of three hours is a harsh reality to confront. Yet, if it’s all made up, one escapes, however briefly, the eventuality that we all face. The idea of death, specifically Auder’s death, is introduced early on and functions as a framing device through which the first person ‘fictional narrative’ unfolds. Following a direct address preface, which is equal parts corny, parodic, and playful in its staginess (and must be a jab at contemporary video art), the film opens with Auder standing in disbelief with his doctor who has just relayed some terrible news, the worst possible. Auder has a terminal brain tumour and will soon die if he does not undergo ‘poison’ treatment. Since his plight is irreversible, our macho protagonist refuses medical treatment (who can blame him?) and embarks on a journey of self-evaluation via his tapes.

Through them, the life and times of Michel Auder emerge, told in third person: his move to NYC; his marriage to Viva and their infamous time at the Chelsea Hotel; the birth of their daughter, Alexandra; the dissolution of their marriage; Auder’s ongoing substance abuse; his frustrations with the art world and his attachment to video; the beginning and end of his marriage to Cindy Sherman; his daughter’s graduation, etc., etc. … It becomes near impossible to not fall prey to sentiment – the material is raw, moving, and sometimes unsettling. Despite the privacy, or painfulness of certain situations, the camera was never put away; it was made to bear witness. Auder’s dependency on his video camera is fascinating, given that he was a pioneer video raconteur

(now there are countless websites devoted to this very idea), though also maddening, as, for example, when he speaks in what now are clichés about his heroin use. (‘I’m going to get this monkey off my back,’ he intones.) Clearly an audience awaits; a certain authenticity is lost through conscious construction. Auder never slips too far or too deeply, and is never out of grasp. He repeatedly talks himself through his fuck ups, knowing he’ll make it through, that he can forever prolong life – his and others’ – with his video camera. It alone seems to placate his moments of neuroses.

Armed with his protective shield, Auder has buffered himself through the years. ‘My life is based on my video works,’ he explains. Those around him have not been so lucky. Viva, a consummate exhibitionist, grows fed up with having her every move documented, their already cramped space made all the more claustrophobic by Auder’s incessant filming. And even though he’s acutely aware that Cindy Sherman abhors being on camera, to the point where she’s made a career out of disguise and disfigurement – one which he cannot, alas, compete with – he practically stalks her with his lens. Her darting eyes betray a palpable discomfort, while he ‘O’Dares’ to torment her further. But, as Proust famously said, ‘Only through art can we emerge from ourselves and know what another person sees.’

It may seem a ludicrous leap, but Proust was the ultimate chronicler of his time, melding fact and fiction, sometimes beyond discernment. He proffered an auto-historia (as much as it is an auto-hysteria) funnelled through the human condition, which, let’s face it, will never be cured, like Auder’s growing tumour (which may or may not be real). In The Feature, Auder tells us that the ‘documentary footage seems to be real, and is real, but is not real.’ Not real, never was real, or no longer is real? Proust again: ‘Time, which changes people, does not alter the image we have retained of them.’ Auder has certainly retained a number of images over the years; they are lo fi, swimmy, degraded, veering green and despite their decay, seem to exhibit something of the genuine spirit of those he recorded. His voyeurism runs deep, perhaps a result of his watching – the quality or calibre of his watching. His goal, he says, ‘is to translate the appearance of my time according to my appreciation of it.’ Every bit of reality can give birth to fantasy, to story, to a new reality. This is how we triumph. Or, simply, this is how we get by. But for Auder, capturing everything he sees on video is clearly vocational.

Obviously, The Feature does not reconcile fact and fiction; instead, it blurs the definitions seemingly represented by the film’s two clearly demarcated registers: that of the archival footage and that of the new, theatrical material. In his guise as ‘Michel Auder,’ living a fulsome and extravagant life, replete with beautiful women and a rock-cut pool overlooking Los Angeles, the art world is revealed as a sham, and his character exhibits a repulsive narcissism. And yet, when caught in quiet moments, something poignant emerges – a glimmer of truth that rebels against the entire endeavour. Or maybe, that’s what makes The Feature. The contradiction between the preposterous persona and the cloistered works drains the distance the camera inherently creates. Auder confesses that whatever he’s remembered is in some way fictional. Despite all the transgressions (formal and philosophical), his humanity includes a faith that upsets the pathetic statement that begins this piece. It is in this distrust of fact and fiction that the film ultimately achieves. It takes a lot of patience to get there, but such is life.

(Andréa Picard, Cinema Scope)

Back to top

Date: 26 October 2008 | Season: London Film Festival 2008 | Tags: London Film Festival

THE WORD FOR WORLD IS FOREST

Sunday 26 October 2008, at 7pm

London BFI Southbank NFT3

Julia Hechtman, Small Miracles, USA, 2006, 5 min

Sci-fi hallucinations seem commonplace as Hechtman invokes mysterious natural phenomena: an extreme case of mind over matter.

Neil Beloufa, Kempinski, Mali-France, 2007, 14 min

Speaking in the present tense, interviewees describe their idiosyncratic notions of the future. To the western viewer, the unlikely subjects, stylized settings and atmospheric lighting impart a strange disconnect between science fiction and anthropology.

Brigid McCaffrey & Ben Russell, Tj Tjúba Tén (The Wet Season), USA-Suriname, 2008, 47 min

‘An experimental ethnography composed of community-generated performances, re-enactments and extemporaneous recordings, this film functions doubly as an examination of a rapidly changing material culture in the present and as a historical document for the future. Whether the record is directed towards its subjects, its temporary residents (filmmakers), or its Western viewers is a question proposed via the combination of long takes, materialist approaches, selective subtitling, and a focus on various forms of cultural labour.’ (Ben Russell)

Sylvia Schedelbauer, Remote Intimacy, Germany, 2008, 15 min

Cast adrift in the collective unconscious, Remote Intimacy constructs an allegorical collage from found footage and biographical fragments, exploring cultural dislocation using the rhetoric of dreams.

PROGRAMME NOTES

THE WORD FOR WORLD IS FOREST

Sunday 26 October 2008, at 7pm

London BFI Southbank NFT3

SMALL MIRACLES

Julia Hechtman, USA, 2006, video, colour, sound, 5 min

Small Miracles is a suite of eight video animations in which the artist conjures up and controls forces of nature. Ignoring rational constructs of what is possible, Hechtman creates imaginary works to ground science fiction in the everyday experience. Coupling feminism and natural phenomena, the videos are located in the liminal space between fantasy and the everyday. (Video Data Bank)

www.juliahechtman.com

KEMPINSKI

Neil Beloufa, Mali-France 2007, video, colour, sound, 14 min

Welcome to Kempinski. The people of this mystical and animist place introduce it to us. ‘Today we have a space station. We will soon launch space ships and a few satellites that will allow us to have much more information about the other stations and other stars.’ This science-fiction documentary has no script and its scenario is caused by a specific game rule. Interviewed people imagine the future and speak about it in the present tense. The attractive aspect of the video leads to exotic stereotypes and a fictitious reading of this true anticipation documentary. Kempinski is also a hotel company. The editing is melodic and hypnotic. Shot in Mopti, Mali. (Neil Beloufa)

TJÚBA TÉN (THE WET SEASON)

Brigid McCaffrey & Ben Russell, USA-Suriname, 2008, 16mm, colour, sound, 47 min

BEN: Nöö di mujëë o púu di soní/ Now she’s going to record this. Ée i kë lúku hën, i sa lúku hën / If you want to look at it, you can look at it. Ée já kë lúku hën, já sa lúku hën. / If you don’t want to look at it, you don’t have to look at it.

SAMELIA: Woó lúku hën. / We’ll look at it.

MONI: Joó lúku hën, hën umfa joó dú? / You will look at it, and then what will you do? Joó tá sábi hën? / You’ll understand it?

Tjúba Tén (The Wet Season) is an experimental ethnography recorded in the jungle village of Bendekondre, Suriname at the start of 2007. Composed of community-generated performances, re-enactments and extemporaneous recordings, this film functions doubly as an examination of a rapidly changing material culture in the present and as a historical document for the future. Whether the resultant record is directed towards its subjects, its temporary residents (filmmakers), or its Western viewers is a question proposed via the combination of long takes, materialist approaches, selective subtitling, and a focus on various instances of cultural labours. (Brigid McCaffrey & Ben Russell)

www.dimeshow.com

REMOTE INTIMACY

Sylvia Schedelbauer, Germany, 2008, video, colour, sound, 15 min

Remote Intimacy is a found-footage montage which combines many types of archival documentary footage (including home movies, educational films, and newsreels), with a pseudo-personal narrative, blending various individual recollections with appropriated literary texts. Beginning with an account of a recurring dream, the film is a poetic amplification of memory, and with its associative narrative structure I hope to open up a space for reflection on issues of cultural dislocation. (Sylvia Schedelbauer)

www.sylviaschedelbauer.com

Back to top

Date: 26 October 2008 | Season: London Film Festival 2008 | Tags: London Film Festival

BEN RIVERS AT THE EDGE OF THE WORLD

Sunday 26 October 2008, at 9pm

London BFI Southbank NFT3

An intrepid explorer, Ben Rivers toys with ethnographic tropes whilst roaming free from documentary truth. Encountering those who choose to live apart from society, his nonjudgmental approach presents ‘real life, or something close to it.’ The Edge of the World features several recent works with other films of his choice.

Ben Rivers, Ah Liberty!, UK, 2008, 19 min

In the wilderness of a highland farm, a bunch of tearaways joyride, smash up, tinker and terrorize the way that only children can. Assimilating landscape and livestock, this poetic study contrasts the languid setting with the youngster’s restless energy.

Alexandra Cuesta, Recordando El Ayer, USA, 2007, 9 min

In the shadow of an elevated subway line in Queens, New York, the residents, streets and stores of a Latino community evoke a sense of transience and displacement.

Ben Rivers, Astika, UK-Denmark, 2007, 8 min

Danish recluse Astika has allowed nature to run wild, overgrowing his own habitat to the point that he has no option but to move away. The film is a hazy arrangement in green and gold, all rich textures and lush foliage.

Luther Price, Singing Biscuits, USA, 2007, 4 min

A gospel cry rings out across the decades, disrupted in space and time, fading but resilient.

Ben Rivers, “New Surprise Film”, UK, 2008, c.7 min

A little anticipation never did anyone any harm; you’ll have to be there to find out what it is.

Ben Rivers, Origin of the Species, UK, 2008, 17 min

‘A 70-year old man living in a remote part of Scotland has been obsessed with ‘trying to really understand’ Darwin’s book for many years. Alongside this passion, he’s been constantly working on small inventions for making his life easier. The film investigates someone profoundly interested in human beings, but who has decided to live separately from the majority of them.’ (Ben Rivers)

PROGRAMME NOTES

BEN RIVERS AT THE EDGE OF THE WORLD

AH LIBERTY!

Ben Rivers, UK, 2008, 16mm-on-video, b/w, sound, 19 min

A family’s place in the wilderness, outside of time; free-range animals and children, junk and nature, all within the most sublime landscape. The work aims at an idea of freedom, which is reflected in the hand-processed Scope format, but is undercut with a sense of foreboding. There’s no particular story; beginning, middle or end, just fragments of lives lived, rituals performed. (Ben Rivers)

SINGING BISCUITS

Luther Price, USA, 2007, 16mm, colour, sound, 4 min

Not a gospel vamp not quite ostinato catatonia but a lost and found of looks that sound and return to look again, a choral interlude from the continuing Biscuits/Biscotts series. (Mark McElhatten, New York Film Festival Views from the Avant-Garde)

RECORDANDO EL AYER

Alexandra Cuesta, USA, 2007, 16mm, colour, sound, 9 min

Memory and identity are observed through textures of everyday life in a portrait of Jackson Heights, home to a large Latin American immigrant population. Images of streets, people, and daily rituals render the passing of time in a neighbourhood that becomes a mirror not just of another place, but also of the past. The landscape visually reflects the space as a creation of a new home while revealing displacement within the new condition. The meaning of home is explored and build upon collective reflection. (Alexandra Cuesta)

ASTIKA

Ben Rivers, UK-Denmark, 2007, 16mm, colour, sound, 8 min

A portrait of Astika, who lives on an island in Denmark. He has lived in a run down farmhouse for 15 years and his project has been to let the land around him grow unchecked, but now he has been forced to move out by people who prefer more pristine neighbours. (Ben Rivers)

A WORLD RATTLED OF HABIT

Ben Rivers, UK, 2008, 16mm-on-video, colour, sound, 10 min

A day trip to Suffolk, to see my friend Ben and his dad Oleg. (Ben Rivers)

ORIGIN OF THE SPECIES

Ben Rivers, UK, 2008, 16mm, colour, sound, 17 min

The film is a portrait of ‘S’, a 70 year old man living in a remote part of Scotland, who has been obsessed with ‘trying to really understand’ Darwin’s book for many years. Alongside this passion, there has been constant work on small inventions for making his life easier. His house is miles down a dirt track and has a grass roof. This film will investigate someone profoundly interested in human beings, but who has decided to live separately from the majority of them. (Ben Rivers)

‘Ah Liberty!’ is being projected on film in the exhibition ‘Wild Shapes’ at Cell Project Space, 258 Cambridge Heath Road, London, E2 9DA, until 16th November. www.cell.org.uk

Back to top

Date: 2 November 2008 | Season: Ken Jacobs tank.tv | Tags: Ken Jacobs, tank.tv

STAR SPANGLED TO DEATH

Sunday 2 November 2008, 2pm-10pm

London Chisenhale Gallery

A free screening of Star Spangled to Death, Ken Jacobs’ episodic indictment of American politics, religion, war, racism and stupidity, timed to coincide with the US election and the end of the Bush regime. Starring Richard Nixon, Nelson Rockefeller, Mickey Mouse, Al Jolson and a cast of thousands.

Ken Jacobs, Star Spangled to Death,1957-59/2004, USA, 400 min

Jacobs’ extraordinary epic combines whole found films, documentaries, newsreels, musicals and cartoons with improvised performances by the legendary Jack Smith and Jerry Sims. Together they picture a dangerously sold-out America where racial and religious prejudice, the monopolisation of wealth and an addiction to war are opposed by Beat generation irreverence.

Star Spangled to Death will be shown with several intermissions. Refreshments available, or bring a packed lunch and a cushion!

Presented by Whitechapel at the Chisenhale, in collaboration with Mark Webber, tank.tv and Firefly. An online exhibition at www.tank.tv from 1 October to 30 November 2008 includes a selection of 20 complete or excerpted works by Ken Jacobs, dating from 1956 to the present.

PROGRAMME NOTES

STAR SPANGLED TO DEATH

Sunday 2 November 2008, 2pm-10pm

London Chisenhale Gallery

STAR SPANGLED TO DEATH

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1957-59/2004, video, b/w & colour, sound, 400 min

Star Spangled To Death is an epic film costing hundreds of dollars! An antic collage combining found-films with my own more-or-less staged filming (I once said directing Jack and Jerry was like directing the wind). It is a social-critique picturing a stolen and dangerously sold-out America, allowing examples of popular culture to self-indict. Race and religion and monopolisation of wealth and the purposeful dumbing down of citizens and addiction to war become props for clowning. In whimsy we trusted. A handful of artists costumed and performing unconvincingly appeal to audience imagination and understanding to complete the picture. Jack Smith’s pre-Flaming Creatures performance is a cine-visitation of the divine (the movie has raggedly cosmic pretensions). His character, The Spirit Not Of Life But Of Living, celebrates Suffering, personified by poor rattled fierce Jerry Sims, as an inextricable essence of living.

I was 24 when I began the film, Jack 25. Jerry in his mid-thirties seemed middle-aged to us. Jack later said, I think appreciatively, I taught him to hate America. We met 1954 and got to hanging around, broke most of the time, walking the streets “shadow starved” (Jack’s expression) for movies a mind could fix on. Max Ophuls’ Sins Of Lola Montez, even in its producer-reassembled state, stood out in its love of the art, in showing what a camera could still do. Hollywood with some few exceptions had gone numb, frantic and numb in this time of fascist ascendance and cultural impoverishment. The enemy had been switched from Right to Left at the end of World War II and the owners had returned with a vengeance. Their message was simple: “Shut up and do what you’re told.” War had done the trick of loosening industry from its Depression fix and war would now be America’s raison d’être. War would serve to rid the country of excess wealth, lest more equitable distribution shake its class structure. In light of how much bullshit it takes to win a war, consider the bullshit it takes to sell ongoing war-to-war-to-war; we were inundated. Only the Abstract-Expressionist painters had been left to proclaim the old radical hopes (because the liberties they took were abstract). The Sixties were nowhere in sight.

Then one day on the set (the rear courtyard of the W. 75 St. brownstone where I was janitor) Jack pushed a copy of ‘On The Road’ into my hands, saying, “It’s about us.” I’d been reading Paul Bowles and H.P. Lovecraft and a smuggled in copy of ‘Lolita’ and the drop in writing level was too steep. “You’ll be able to stay with it on your sixth attempt”, Jack said, which proved to be true. It caught some things right, quirky ephemerals that hadn’t registered as events. Of course it helped stir a social revolution (disowned by Kerouac) and maybe Star Spangled To Death would’ve participated in that great humanist eruption if I had completed it and got it out in its proper time. Over six hours then, there was no way I could pay final sound-joining and printing lab costs. I screened camera originals a few times to records and spoken commentary but money didn’t happen and, pissed, in 1963 I put it aside to continue with affordable works (like near cost-free shadowplay). Its moment, I felt, had passed. Its invention, the very look of it, its texture was to a degree no longer unique. My pride was wounded. People were treating me as if I was normal. I got a measure of Jack’s fame when I heard a girl address her dog as Flaming Creature, but he chose – at a time when patrons were available to him – not to help. Like maybe his movie might be seen as coming from somewhere. I let it go and had another life, better I’m sure than the one that would’ve resulted from the release then of Star Spangled To Death.

I recall thinking when Kennedy took office there was less urgency to get it out. He looked like he had a sex life, had little kids that he surely wanted to raise above-ground, and indeed he did interfere with the Eisenhower plan to return Cuba to The Mob, costing him his life.

Video makes its present release possible. Yeah, yeah, it ain’t film, and I’d already begun my quest with it into the actuality of film rather than film as transparency. Rising from my own abstract-expressionist mindset. Let me be. I so appreciate what video permits (although the work, with one sinful exception, the reprise of ‘Are You Havin’ Any Fun?’, does not take off into electron free-play but stays respectful of film limits), and I appreciate the possibility of cheap DVD distribution. And if anyone has the passion and money and patience the video can guide final assembly of the film. At age 70 I have to attend to other cine-demands, like leaving something lasting of what Flo and I did in live performance with The Nervous System and Nervous Magic Lantern.

“Something lasting”? Habit of thought. I wonder if our masters (the hallowed image of The White House insists, to the subconscious, that The Old Plantation prevails) figure, in rationalising a way to live with their crimes, that “natural death” is often no less painful than an accelerated conclusion, so what the hell, the little fuckers will replenish their numbers soon enough. From where they are we all look alike, excepting those of us that stand up. I don’t feel hopeful when Bush lies are exposed, implausible to begin with; followers elect to believe, and hold on to beliefs doggedly. Followers expect leaders to lie and believing an obvious lie is how they demonstrate their faith. Lying mostly offends professors and not all of them by a long shot. No, I think we’re due to be interrupted, that history is about to come down through the roof on us this time. Sorry, truly, but I believe my film-title. Perhaps that it arose to mind almost a half-century ago and so many of us are still here, in sight of scientific breakthroughs galore, is reason for confidence in ongoing life. We certainly can resist the bastards! They are taking our lives, what more can we lose? Jack fumbled the making of his last film but how meaningful a title is No President.

Here, explaining, you get gravity. The movie achieves levity.

Is this video the real thing? In the winter of 1959 editing facilities were two nails in a wall holding two film reels and an enlarging glass and in 2003 a G4 with Final Cut Pro. Better to figure the entirety as another entry in my found-film oeuvre. I did drop some found-films from the original collage, including all biographic elements (like my maybe-father’s third-wedding home-movies), replacing with items more on track with central concerns of the work. Stuff gathered over the years with SSTD in mind, only some that could be squeezed into its ultimate realisation. The Follies entered sometime in the Sixties, the Micheaux entered my life with a bang in 1968 (Ten Minutes To Live being up there with the greatest; the DVD of SSTD should by rights be a double-feature with Ten Minutes To Live seeing as the titles go so well together) but only infiltrated SSTD during this latest editing. Ronald Reagan and the twerp presiding now, how ignore them? Perhaps with precisely the same pitch of outrage as my younger self I would not have made any concessions to audience capacity, only added things. There’s friends, I know, that will be glum over what they will perceive as signs of an orderly mind. My head, inside, isn’t all that different from what it was, I didn’t become someone else, but I did get the work together and in a profound way that’s the problem. It was supposed to lie in a jumbled heap, errant energies going nowhere, the talented viewer inferring form. A Frankenstein that fizzled but twitching and still dangerous to approach. Thoroughly star spangled but still kicking. —Ken Jacobs

Back to top

Date: 14 November 2008 | Season: Robert Beavers 2008 | Tags: Robert Beavers

ROBERT BEAVERS

14—16 November 2008

Norwich Aurora Festival

Robert Beavers has laboured in relative isolation on works whose goal “is for the projected film image to have the same force of awakening sight as any other great image.” His meticulously crafted films are at once lyrical and rigorous, sensuous and complex. Whilst communicating his response to the landscapes, architecture and traditions of the Mediterranean and Alpine countries in which they were filmed, they also incorporate deeply personal and aesthetic themes.

The films Beavers made between 1967 and 2002 are collected together in the cycle “My Hand Outstretched to the Winged Distance and Sightless Measure”, which comprises 17 individual titles and a prologue. Since finishing this series, he has embarked on new works, beginning with Pitcher of Colored Light in 2007.

Robert Beavers was born in Brookline, Massachusetts, in 1949, attended Deerfield Academy and developed an interest in cinema from an early age. Encouraged to make his own films, he moved to New York in 1965 and met the Greek-American filmmaker Gregory J. Markopoulos. Two years later Beavers relocated to Europe, where he was soon joined by Markopoulos, and embarked upon a peripatetic lifestyle travelling and filming across several countries.

Beavers’ filmmaking began in earnest with several works being completed in the space of three years. The earliest films, from Winged Dialogue to Still Light, shot variously in Greece, Belgium, Switzerland, Germany and England, are stylistically adept whilst displaying a youthful dynamism. Made when the filmmaker was only 18 to 21 years old, they suggest a sense of adolescent isolation and angst. Diminished Frame, a bleak view of Berlin, powerfully conveys the alienation felt by the filmmaker during his first visit there in 1970.

Together, the Early Monthly Segments form a prologue to the complete cycle, and is the only silent film. Excerpts are also included on reels containing the final versions of the six early films. These brief exercises apply formal experimentation to personal footage or daily imagery. Whilst offering a glimpse into the lives of Beavers and Markopoulos, they more significantly demonstrate Beavers’ enthusiasm for and exploration of his chosen medium.

Beavers’ frequently manipulates the field of vision by inserting coloured filters, applying mattes that selectively reframe or block out the image, and by turning the lens on the turret of the camera. The rapid, diagonal motion that arises from the latter device is echoed by the unconventional use of swift pans and tilts.

From the Notebook of … is an axis on which the two phases of Beavers’ oeuvre are balanced, being a point of convergence between the impulsive early works and the more considered manner of his mature films. It was inspired by the notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci (and writings by Giorgio Vasari and Paul Valéry), and depicts Beavers’ own filming notes, work room and creative process in relation to views of Leonardo’s Florence and details of the Renaissance artist’s life.

The self-reflexive nature of the filmmaking is most evident in the early films but continues as a presence in later works in which Beavers frequently draws parallels between the act of filmmaking and the craft of skilled labour. These formal characteristics, often associated with the structural tendency, are tempered by the lyrical qualities of the work, and its intimate relationship to landscape, culture, architecture and history.

Work done, a stately chain of elementary images that range from the natural world to artisanal production, marks the beginning of a new approach. From this point onwards, films were no longer centred on a protagonist, but were built on the implied correspondences between objects or visual emblems, conveying emotions and thoughts in an innate or tacit manner. When human figures appear, they act as metaphoric symbols, rarely as characters or subjects.

The film Ruskin was motivated by Beavers’ reading of “The Stones of Venice”. Architectural details and views of the Italian city dominate the film, which also features images of London and the Alps, and a copy of “Unto This Last”, Ruskin’s treatise on social justice. Though literature is one of Beavers’ sources of inspiration, his films seldom contain text or speech. Dialogues are created between images rather than through the use of language.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Beavers’ films were rarely shown in public. Both he and Markopoulos lived modest lives, dedicated to making new work and ensuring the means to continue, independent even of the support structures and community that had formed around the avant-garde cinema in New York and Europe.

In AMOR, as in the later film The Hedge Theatre which was also shot in Rome, analogies are drawn between filmmaking, tailoring and architecture. Images or sounds of the making of a suit, the restoration of a building and of Beavers himself are cut together in complex sequences. The filmmaker’s hand gestures, which frequently reach out into the frame, emphasise a performative element in the making.

The final series of films in the cycle were predominantly shot in Greece and include Efpsychi, photographed in the old market quarter of Athens, and Wingseed, partly located in an idyllic landscape near to where Beavers and Markopoulos presented annual outdoor screenings between 1980 and 1986.

In 1992, shortly after completing the editing of his monumental work ENIAIOS, Gregory Markopoulos died in Freiburg, Germany. The Ground, made over the subsequent eight years, is Beavers’ moving response to this loss. One of the film’s signature images, the ruins of a hollow tower on a hillside above the sea, is also featured in Winged Dialogue, and brings a sense of completion and circularity to the entire sequence of works when viewed in its entirety.

The unity of the cycle was reinforced by the process of re-editing undertaken by Beavers in the 1990s. These revisions typically created shorter films, producing distilled works that are painstakingly composed and precisely balanced. At this time, he also created many new soundtracks, often returning to the original sites to record audio on location.

As Beavers reached the conclusion of this process, he began to show his work at selected screenings, most notably at festivals in New York, Rotterdam, Toronto and London. This cautious but considered emergence into the public arena finally gives audiences the opportunity to survey his intricately crafted style of filmmaking. “My Hand Outstretched to the Winged Distance and Sightless Measure” offers the contemporary viewer a rare aperture for vision, communicated in the moment of projection. The complete cycle has been presented at the Whitney Museum of American Art (October 2005) and Tate Modern (February 2007), and selections have screened at museums, archives and cinematheques worldwide.

For the first film since the 17-film cycle, Beavers returned to the USA to photograph the solitude of his mother’s house in New England. Employing a more intimate approach to filming, he created a tender portrait which contrasts a dark interior with the vibrancy of an abundant garden. On the soundtrack ambient natural sounds are punctuated by brief phrases of his mother’s voice or passages of music from the radio. As seasons pass, the camera searches through shadows, conveying the slowed pace of life in old age.

Parallel to his ongoing practice as a filmmaker, Beavers remains responsible for the legacy of Gregory J. Markopoulos and for developing the Temenos Archive which they jointly conceived for the preservation and promotion of their work. Born out of the desire for continuity between the production, presentation, and interpretation of their films, the project proposes a facility in which a projection space, the film copies, and the filmmakers’ writings and documentation can exist in close proximity. In this environment, dedicated spectators would have the possibility to view and study the films in tandem.

This ideal was first articulated by Markopoulos in essays published through the last two decades of his life, and has since been taken forward by Beavers in more practical terms of both conservation and public access. Numerous films by both filmmakers have been preserved, and new prints have been exhibited at venues in Europe and North America. An archive has been established in Zürich, in which the private papers, journals, essays, production notes of Beavers and Markopoulos, plus documentation such as publications, critical writing, posters, photographs and other materials can be stored and made available for research.

A primary focus of Temenos activity is the costly and labour intensive restoration and printing of ENIAIOS, the 80-hour long film that Markopoulos considered a summation of his filmmaking knowledge. ENIAIOS interweaves approximately 100 individual works including radically reedited versions of his best-known early films and others that have not been shown in any form.

This uniquely ambitious film was made specifically for showing in a remote, outdoor location in Arcadia, Greece, where the two filmmakers had presented annual screenings for seven years in the 1980s. In 2004 and 2008, Beavers returned to this site to present the first screenings of the opening hours of ENIAIOS’ to an international audience. The act of travelling to the site, spending some days away from daily life, and the opportunity of viewing a work in total harmony with its surroundings is extraordinarily affecting.

Beavers often speaks of filmmaking as a “search”, and this is also the process a viewer undergoes when first encountering his films, which are in extraordinary contrast our customary experiences of the moving image. His films, and the example of the Temenos, which proposes a new way for filmmakers to articulate their works beyond the frame, are testament to a dedication to the medium and its audience. —Mark Webber

ROBERT BEAVERS FILMOGRAPHY

Winged Dialogue, 1967/2000, and Plan of Brussels, 1968/2000, 35mm, colour, sound, 21 min

Early Monthly Segments, 1968-70/2002, 35mm, colour, silent, 33 min

The Count of Days, 1969/2001, 16mm, colour, sound, 21 min

Palinode, 1970/2001, 16mm, colour, sound, 21 min

Diminished Frame, 1970/2001, 16mm, black-and-white and colour, sound, 24 min

Still Light, 1970/2001, 16mm, colour, sound, 25 min

From the Notebook of …, 1971/1998, 35mm, colour, sound, 48 min

The Painting, 1972/1999, 16mm, colour, sound, 13 min

Work done, 1972/1999, 35mm, colour, sound, 22 min

Ruskin, 1975/1997, 35mm, black-and-white and colour, sound, 45 min

Sotiros, 1976-78/1996, 35mm, colour, sound, 25 min

AMOR, 1980, 35mm, colour, sound, 15 min

Efpsychi, 1983/1996, 35mm, colour, sound, 20 min

Wingseed, 1985, 35mm, colour, sound, 15 min

The Hedge Theater, 1986-90/2002, 35mm, colour, sound, 19 min

The Stoas, 1991-97, 35mm, colour, sound, 22 min

The Ground, 1993-2001, 35mm, colour, sound, 20 min

Pitcher of Colored Light, 2007, 16mm, colour, sound, 24 min

Back to top

Date: 14 November 2008 | Season: Robert Beavers 2008

ROBERT BEAVERS: PROGRAMME 1

Friday 14 November 2008, at 3:30pm

Norwich Aurora Festival

EARLY MONTHLY SEGMENTS

Robert Beavers, 1968-70/2002, 35mm, colour, silent, 33 min

Cast: Robert Beavers, Gregory Markopoulos, Tom Chomont

Filmed in Switzerland, Germany (Berlin) and Greece.

I began with a decision to film a self-portrait at monthly intervals and to explore the space that extends from the aperture to immediately in front of the camera and then to my surroundings. After a few months of these (self) reflections and examinations of the Bolex camera’s possibilities, I began to include also portraits of Gregory Markopoulos, with whom I was living and travelling and whose dedication to filmmaking I was constantly observing. Slowly I became aware of my intention to make certain features of the camera articulate. One of the first was the use of the space for coloured gelatine filters found between the lens and the aperture. This is a space in which I placed very small pieces of gelatine filters to colour different parts of the frame. Later I noticed that the movement of sliding the pieces of filters into the filter slot reversed the vertical order of the colours at a certain point in the sliding movement. There was a sudden sense of discovery when I consciously saw this happen. I reflected about this reversal of the order of the filters and began to work with the camera as an analogue to the senses. In this case to the reversal of the image within sight. That sounds more abstract than it was, and, when I think about it now at such a distance in time, I see a more general connection between the intention to film a self-portrait and this (self) reflection about the articulate quality or vitality of the camera’s features. (Robert Beavers)

AMOR

Robert Beavers, 1980, 35mm, colour, sound, 15 min

Cast: Robert Beavers

Filmed in Italy (Rome, Verona) and Austria (Salzburg)

Like the roots of a plant reaching down into the ground, filming remains hidden within a complex act, neither to be observed by the spectator not even completely seen by the filmmaker. It is an act that begins in the filmmakers’ eyes and is formed by his gestures in relation to the camera. In a sense he surrounds the camera with the direction of his intuition and feeling. The result retains certain physical qualities of the decisive moment of filmmaking – the quality of light and space – but it is equally surprising how a filmmaker draws what he searches for towards the lens. (Robert Beavers)

THE GROUND

Robert Beavers, 1993-2001, 35mm, colour, sound, 20 min

Cast: Robert Beavers

Filmed in Greece (Island of Hydra)

What lives in the space between the stones, in the space cupped between my hand and my chest? Filmmaker/stonemason. A tower or ruin of remembrance. With each swing of the hammer I cut into the image and the sound rises from the chisel. A rhythm, marked by repetition and animated by variation; strokes of hammer and fist, resounding in dialogue. In this space which the film creates, emptiness gains a contour strong enough for the spectator to see more than the image – a space permitting vision in addition to sight. (Robert Beavers)