Date: 16 October 2004 | Season: Valie Export

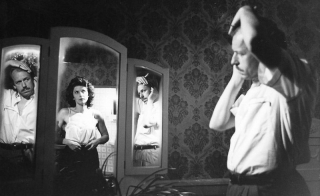

THE PRACTICE OF LOVE

Saturday 16 October 2004, at 8:40pm

London National Film Theatre NFT2

The Practice of Love is a thriller in which television journalist Judith Wiener investigates the events that led to a fatal subway accident, revealing facts which implicate her two lovers in a terrorist conspiracy. Alfons seems out of his depth with his involvement with an arms smuggling racket, while Joseph is a respected psychologist who appears unable to manage his own emotional affairs. The film explores what goes on just below the surface, and how this affects private and public behaviour.

Valie Export, The Practice of Love (Die Praxis der Liebe), Austria, 1984, 90 mins

with Adelheid Arndt, Rüdiger Vogler and Hagnot Elischka

Also screening: Wednesday 20 October 2004, at 6:20pm

Date: 17 October 2004 | Season: Valie Export

VALIE EXPORT: MEDIAL ANAGRAMS

Sunday 17 October 2004, at 6:20pm

London National Film Theatre NFT2

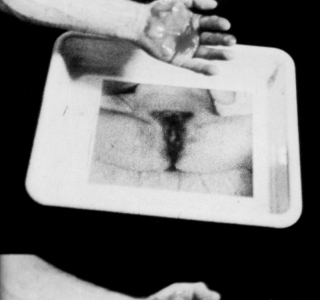

Export’s work in film and video often focuses on the meaning, transformation and identity of signs and the way they are interpreted and represented as reality by the technological media. The visceral early films Mann & Frau & Animal and … Remote … Remote … address these issues in a direct and explicit manner. Syntagma, from 1983, is a complex visual montage in which her entire film, expanded cinema and visual art techniques are concentrated into a work that explores the female body as sign. The screening also includes A Perfect Pair, an allegorical depiction of consumer lust from the portmanteau film Seven Women – Seven Sins, and the video works Seeing Space and Hearing Space and The Duality of Nature.

Valie Export, Interrupted Line, Austria, 1971-72, 16mm, 3 mins

Valie Export, Mann & Frau & Animal, Austria, 1973, 16mm, 10 mins

Valie Export, … Remote … Remote …, Austria, 1973, 16mm, 10 mins

Valie Export, Raumsehen und Raumhören, Austria-Germany, 1974, video, 20 mins

Valie Export, Die Zweiheit Der Natur, Austria, 1986, video, 2 mins

Valie Export, Syntagma, Austria, 1983, 16mm, 18 mins

Valie Export, Ein Perfektes Paar, Oder Die Unzucht Wechselt Ihre Haut, Austria-Germany, 1986, video, 12 mins

In a rare appearance, Valie Export will be present on 17 October 2004 to discuss her work with writer and curator Ian White.

Also screening: Wednesday 20 October 2004, at 8:40pm

Date: 30 October 2004 | Season: London Film Festival 2004 | Tags: London Film Festival

THE TIMES BFI 48th LONDON FILM FESTIVAL

Saturday 30 – Sunday 31 October 2004

London National Film Theatre

As with last year, the Experimenta Avant-Garde Weekend will present a concentrated, international programme of artists’ film and video. It is a unique opportunity to survey some of the most original and vital works made around the world in recent years, and our only annual chance to do so on such a scale in England.

This year’s festival includes new films by old masters such as Bruce Conner, Peter Kubelka and Jonas Mekas, alongside work by younger artists including Michaela Grill, Julie Murray and Emily Richardson. There is an opportunity to discover the work of forgotten pioneer José Val del Omar, and featured artist Nathaniel Dorsky will present a lecture to introduce his exquisite silent films. All the mixed programmes plus selected features will be shown over the two-day period, and several of the filmmakers will be present to discuss their work.

Outside of the weekend, the festival also features screenings of Jennifer Reeves’ feature The Time We Killed, Gianikian & Ricci Lucchi’s Oh, Uomo, both versions of Straub / Huillet’s Une Visite au Louvre and a newly preserved print of Shirley Clarke’s Portrait of Jason.

Date: 30 October 2004 | Season: London Film Festival 2004 | Tags: London Film Festival

VIDEO VISIONS

Saturday 30 October 2004, at 2pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

fordbrothers, Preserving Cultural Traditions in a Period of Instability, Austria, 2004, 3 min

fordbrothers explode the visual field as a strangely familiar, but unidentified, voice rails against computer technology and modern society.

Fred Worden, Amongst the Persuaded, USA, 2004, 23 min

The digital revolution is coming, and an old-school film-maker is trying to come to terms with it. ‘The human susceptibility to self-delusion has, at least, this defining characteristic: Easy to spot in others, hard to see in oneself.’ (Fred Worden)

Didi Bruckmayr & Michael Strohmann, Ich Bin Traurig, Austria, 2004, 5 min

An aria for 3D modelling, transformed and decomposed using the cultural filters of opera and heavy metal.

Robin Dupuis, Anoxi, Canada, 2003, 4 min

Effervescent digital animation of vapours and particles.

Michaela Grill, Kilvo, Austria, 2004, 6 min

Minimal is maximal. A synaesthestic composition in black, white and grey.

Myriam Bessette, Nuée, Canada, 2003, 3 min

Bleached out bliss of dripping colour fields.

Jan van Nuenen, Set-4, Netherlands, 2003, 4 min

Endless late night cable television sports programmes, remixed into deep space: from inanity to infinity.

Robert Cauble, Alice in Wonderland Or Who Is Guy Debord?, USA, 2003, 23 min

Alice longs for a more exciting life away from Victorian England, but is she ready for the Society of the Spectacle? Conventional animation is subverted to tell the strange tale of Alice and the Situationists.

PROGRAMME NOTES

VIDEO VISIONS

Saturday 30 October 2004, at 2pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

PRESERVING CULTURAL TRADITIONS IN A PERIOD OF INSTABILITY

fordbrothers, Austria, 2004, video, colour, sound, 3 min

Preserving Cultural Traditions in a Period of Instability is a computer-generated video based on artefacts occurring during compression procedures. A short hypnotic and monotonous sound-loop underlines the structural character of the video footage, whilst a commentary by Stan Brakhage on the rise of digital technologies and new media forms the second sound layer. (Thomas Draschan)

AMONGST THE PERSUADED

Fred Worden, USA, 2004, video, colour, sound, 23 min

The human susceptibility to self-delusion has, at least, this defining characteristic: Easy to spot in others, hard to see in oneself. This film began as an effort to channel the stresses engendered by my daily New York Times fix. The news of the world read as a relentless collective descent into a 21st century Jonestown. More accurately, into a scattered offering of competing Jonestowns, each proffering its own distinctive brand of cool aid. In the free marketplace of mindsets, you’re free to choose your poison. Each of us sees things in our own way. What I was seeing was that the common denominator driver of so many of the man-made disasters charted in each day’s New York Times was the human penchant for delusional thinking. The war on terror, to cite only one simple example, seemed to me essentially reducible to their delusions versus our delusions, with the stakes being who will be the first to have its ass handed to it. My decision to make the mechanics and infrastructure of self-delusion the subject of a film was easy enough once I committed to two operating principles. The first was that the film had to be about my delusions and those of my milieu rather than about their delusions. The second, somewhat contradictory principle is that it really is impossible to see one’s own delusions. The essence of self-delusion as pathology is that it is at all times invisible to its host. For this reason, I could not cast this film with my actual delusions, but rather had to work with analogue surrogates. This suited my purposes just fine as my interest was never with the actual content of delusional thinking, but rather with its forms. How we get there, move in, make ourselves comfortable and then bend our talents to defending the fort. How the most gracious and nimble of mental eruptions can end up tripping down the slippery slope from inspired possibility through true belief to leaden and entrenched delusion. With a cast of available characters acting as themselves. Don’t believe a word. See the iron jaws of the mechanism at work as the filmmaker falls into the biggest and most obvious delusion of all: the belief that he can master his own delusions by making a film about them. (Fred Worden)

ICH BIN TRAURIG (I AM SAD)

Didi Bruckmayr & Michael Strohmann, Austria, 2004, video, colour, sound, 5 min

Ich Bin Traurig (I am sad) is part of a series of works on “digital translations of reality” (Didi Bruckmayr). Fuckhead – one of the band projects of cultural workers Bruckmayr/Strohmann – is one of these translation projects. The masculinity-charged raging of brachial heavy metal music runs – analogue to the technical processes of sound mixing – through the filter of another cultural form of expression: the opera and its melodramatic employment of voices, as well as the distant, cool, electronic creation of sound. The result is a bastard, a science-fiction being whose existence grows increasingly precarious. Fuckhead possibly tells – in image and sound and data – of human sensibilities at the edge, of that which the author J.G. Ballard calls “psychopathologies of the future” (in his epochal novel Crash). The expression quite aptly represents this video. Its “clinical picture” is that of the love sick, intense sorrow at the loss of love: “I am sad, because you do not understand me / melancholy steals my sleep at night.” Siemar Aigner’s pathetic bass drowns out the scratchy surface of electronic accompaniment. The antagonism between the Spartan electronics, which tend to refuse to lead the melody, and the presence of a human voice is mirrored in the visual translation of the number: the image of a human face (created in a computer by means of 3-D software) is horizontally deformed to the rhythm of the verse, disheveled along the lines of the acoustic information from the computer. When the song stops, black takes over the picture and narrows the narrative space down to music. The absence of the human element is heavier (textually, as well as visually) than its presence. (Michael Loebenstein)

ANOXI

Robin Dupuis, Canada, 2003, video, colour, sound, 4 min

The images are generated frame by frame as stills, usually generated from simple shape or forms (square, circle, line etc.), and processed in various commercial software (Photoshop, Vegas, DL Combustion) and/or open source software (Drone, Bidule), before and/or after being edited in sequence. I produce a lot of images and animated sequences to create what I call an image bank, from which I select parts for each project I work on. I do the same for sound. The image and sound in Anoxi is pure synthesis, there is no capture, scan or recording of external material of any sort. (Robin Dupuis)

KILVO

Michaela Grill, Austria, 2004, video, b/w, sound, 6 min

A remote, barren, almost unfriendly landscape: Kilvo in Lapland was the inspiration for Radian’s music, and even the accompanying visuals by Michaela Grill play with the bare countryside’s resistance to its depiction. A fourfold split screen shows views of this place in a kaleidoscope of animated digital postcards. The normal associations – visions of majestic, or at least marketable, beauty, of exotic or untouched wilderness – are consistently undermined in Kilvo. Instead of showing an idyll, the landscape is reduced to the greatest degree possible. Lines and contours are stripped from the background of black, white and grey tones. The viewer cannot be sure what is being shown, or implied. For brief moments fleeting images appear then change or are lost. Faithful reproductions are not the important thing here, but the digital transformation of a real landscape into an abstract pattern, translation into a completely different visual form, which at the same time conforms to this landscape. For all its reduction and structural austerity Kilvo also has a playful aspect. The movement in the screen sections is tied to the articulated rhythm of the music and its modulation. The sounds and images are combined in an entertaining and complex game with structures, and with musical and visual synchronisms. In the end everyone can invent Kilvo for themselves. In their reservation and simultaneous openness, the sounds and images offer a projection screen for the viewers’ mental images, for the search for their own imaginary landscape. (Barbara Pichler)

NUÉE

Myriam Bessette, Canada, 2003, video, colour, sound, 3 min

Though synthetically constructed, the fleeting works of Myriam Bessette bring rare tactile qualities to the digital medium. Her earlier videos Nutation and Azur bestowed an organic delicacy to the pure cathode ray signal. In Nuée, streaks of muted hues merge to form a constantly shifting colour field that is overlaid with abstract verdant flecks. The sensorial experience is heightened by a fizzing electronic soundtrack. (Mark Webber)

SET-4

Jan van Nuenen, Netherlands, 2003, video, colour, sound, 4 min

On the TV station Eurosport, the hours between the really exciting matches are filled up with sports pulp. You see endless games, sets and matches ‘live’, accompanied by lethargic commentary. Out of exasperation, Jan van Nuenen recorded three examples of this, which he mixed, overlapped and superimposed into loops. What starts as an ordinary game of ping-pong develops into a kaleidoscopic spiral of dancing high servers, flying springboard divers and rhythmically chopping table-tennis bats. Eventually it becomes a scene that appears to represent the culmination of a bizarre acid dance party. (Jaap Vinken & Martine van Kampen)

ALICE IN WONDERLAND OR WHO IS GUY DEBORD?

Robert Cauble, USA, 2003, video, colour, sound, 23 min

Alice in Wonderland, or Who Is Guy Debord? pairs footage from the Disney cartoon with an alternate sound track. Alice’s quest for the help of philosopher Guy Debord (The Society of the Spectacle) is punctuated by an assaultive TV montage that includes Bush’s aircraft carrier landing. (Chicago Reader)

Back to top

Date: 30 October 2004 | Season: London Film Festival 2004 | Tags: London Film Festival

TRAVEL SONGS

Saturday 30 October 2004, at 4pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

Robert Breer, What Goes Up, USA, 2003, 5 min

A volley of rapid visual associations from the mind of Robert Breer, animating collage, drawings and snapshots in a playful, but rigorous manner. What goes up must come down.

Jonas Mekas, Travel Songs 1967-1981, USA, 2003, 24 min

In short bursts and single frames, memories of European journeys rush by like landscapes through train windows. This ebullient album of previously unseen footage contains songs of Assisi, Avila, Moscow, Stockholm and Italy.

Frank Biesendorfer, Little B & MBT, USA-Germany, 2003, 30 min

An intimate journal featuring the film-maker’s family in their daily life, contrasted with audio recorded at one of Hermann Nitsch’s actions in his Austrian castle. Despite their diverse sources, the sound and image weave a tangled spell around each other.

Robert Fenz, Meditations on Revolution V: Foreign City, USA, 2003, 32 min

The Meditations series comes home for a journey through New York, viewed as a place of immigration and displacement. The urban environment, shot mostly at night in ecstatic black-and-white, becomes an almost exotic locale. Fenz’s incandescent cinematography reveals images of great beauty and compassion on the sidewalks and subway, as the film subtly shifts from anonymous street scenes into a sensitive portrait of jazz legend Marion Brown, who reminisces on his life and career as he convalesces in hospital.

PROGRAMME NOTES

TRAVEL SONGS

Saturday 30 October 2004, at 4pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

WHAT GOES UP

Robert Breer, USA, 2003, 16mm, colour, sound, 5 min

In observance of gravity – the airplane, the priapic flesh, the deciduous leaf, the upturned nose, the kitten up a tree, the towering Empire – All Must Fall. As a man who fell to earth Breer branches off into playful tangents and bursts creating complex spaces cartwheeling through time’s latest seasons. Quick as a snapshot, hard as a slingshot, lighter than a ton of feathers. (Mark McElhatten, New York Film Festival Views from the Avant-Garde)

TRAVEL SONGS 1967-1981

Jonas Mekas, USA, 2003, 16mm, colour, sound, 24 min

Mekas’ sublime Travel Songs, each of which run for five minutes or less, communicate the colourful and deepened sense of their varied locales (Italy, Russia, New York, etc). Mekas’ camera is always in motion, restlessly flipping back and forth on seemingly impossible zigzag trajectories. Central to his work is a feeling of forward momentum, Mekas sees the human condition as a hurtling train of experience. The momentary, split-second pauses in his camera movements – often focusing on either the fruits of nature or specific aspects of human physiognomy – suggest myriad paths of understanding and enlightenment. Mekas desperately tries to drink it all in and, happily for him and for us, fails. Like an immortal flower in constant bloom, Mekas’ films are an ever-expanding document of life in perpetual motion, personal profundity at twenty-four frames per second. (Keith Uhlich)

LITTLE B & MBT

Frank Biesendorfer, USA-Germany, 2003, 16mm, colour, sound, 30 min

The soundtrack is made from my recordings of voices, discussions and sounds surrounding a recent Hermann Nitsch action in Austria. The images, consisting primarily of special and intimate moments of his wife and children, intertwine with the audio in strange and ambiguous ways. The film battles itself in order to cancel itself out, but the conflict remains circular and supersedes both the audio and visual, in a place beyond the material and physical. (Frank Biesendorfer)

MEDITATIONS ON REVOLUTION V: FOREIGN CITY

Robert Fenz, USA, 2003, 16mm, colour, sound, 32 min

The final film in Fenz’s series “Meditations on Revolution.” The film is dedicated to the director’s father who immigrated to the United States in 1953 and passed away in 1999. Foreign City studies New York as a place of immigration and displacement. It is a meditation on revolution of the urban space. Its abstract black and white images and actual sounds come in and out of synch, creating a magical foreign landscape. The reconstruction of N.Y. through an imaginary city plan, built on sensation. The film has a timeless, anonymous quality until it is given the voice of artist and jazz musician Marion Brown. (Robert Fenz)

Back to top

Date: 30 October 2004 | Season: London Film Festival 2004 | Tags: London Film Festival

PUBLIC LIGHTING

Saturday 30 October 2004, at 7pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

Mike Hoolboom, Public Lighting, Canada, 2004, 76 min

Public Lighting is a meditation on photography and the creation of images that can capture, replace and outlive our experiences. It’s a videofilm in seven parts, related in both subject and sentiment to the wonderful Imitations of Life, which screened in last year’s festival. Each chapter is a case study of the different types of personality that have been identified by the young author who guides us through the prologue. The first, a gay male, takes us on a tour of the bars and restaurants where his affairs have ended, recounting ironic stories of his many lovers. An homage to composer Philip Glass is incongruously followed by ‘Hey Madonna’, a confessional letter to the singer from a fan who is HIV positive. Amy celebrates another birthday, but concedes that she has lost her memory to television. At least she has a camera: ‘I take pictures not to help me remember, but to record my forgetting.’ Hiro lives life at a distance, rarely venturing out beyond the lens, and an anxious young model recounts poignant events from her past. Few film-makers use re-appropriated footage in such an emotive way: At once humorous and incisive, these chains of images inevitably lead us back to parts of ourselves. Hoolboom’s recent work is in such profound sympathy with the human condition that it speaks directly to our hearts.

PROGRAMME NOTES

PUBLIC LIGHTING

Saturday 30 October 2004, at 7pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

PUBLIC LIGHTING

Mike Hoolboom, Canada, 2004, FORMAT, COLOUR, SOUND, 76 min

“How do we tell the story of a life? What cruel reduction of an image will stand (in the obituary, the family photo album, the memory of friends) for the years between a grave and a difficult birth? Public Lighting examines the current media obsession with biography, offering up “the six different kinds of personality” (the obsessive, the narcissist) as case studies, miniatures, possible examples.” (Mike Hoolboom)

“Mike Hoolboom puts together some disparate clips, some beautiful images and hesitant shots from family, fiction, reality archive and advertising films (the Japanese advertisement for an all-purpose cleaning fabric is hilarious). Some images have been found or borrowed while others are original and have been shot for the purposes of the film. In the images there are also words, uttered in short sentences, and the voices of men and women. But this is only half the story. The filmmaker uses a dual approach to images and sounds to construct his unique universe. On the one hand, he gives them depth by slowdown effects, fade-ins and fade-outs, solarization, intermingling of visuals and sound in a complex dramatisation relationship. Public Lighting thus consists of strong images that show us the ages of history, its moments of grandeur and shame, touching on the public and private spheres, mingling show-biz and intimacy. An image in a Hoolboom film is always multiple, a confusing palimpsest that is embedded at a certain point in a different image, a pagan icon that keeps trace of the movement of a body, the expression of a face, the inflection of a voice. On the other hand, although this magnificently impure film is based on a very elaborate editing rhetoric, its profound movement leads to uninterrupted mediation.

“Public Lighting consists of six portraits which a young writes announces at the beginning of the film. These six people tell of ordinary follies, narcissistic obsessions, demiurgic desires and wounded memories. The separated man, the obstinate pianist, the ageing singer, the Chinese émigré, the nocturnal Japanese and the confessed woman are fragments of a collective history. The warm lighting used by Mike Hoolboom illuminates sleepless nights when one is no longer prepared to be deceived – at least for a while – by the ghostly apparitions that haunt our dreams. A single image then appears to emerge. That of a poetic intelligence worried about the world, in which the grave and lucid Hoolboomian hero aspires to some recognition, to a semblance of eternity and to a ‘genuine’ place in the movement of life.”

(Jean Perret, Visions du Reel Catalogue)

Back to top

Date: 30 October 2004 | Season: London Film Festival 2004 | Tags: London Film Festival

POETRY AND TRUTH

Saturday 30 October 2004, at 9pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

Larry Jordan, Enid’s Idyll, USA, 2004, 17 min

An animated imagining of Arthurian romance based on Gustav Doré’s engraved illustrations for Tennyson’s ‘Idylls of the Kings’, accompanied by the music of Mahler’s ‘Resurrection Symphony’.

Julie Murray, I Began To Wish, USA, 2003, 5 min

Mysterious events unfold in a potting shed … A jewel of found footage, mysterious and profound beyond its imagery, and with an almost deafening aural presence, despite its lack of soundtrack.

Rebecca Meyers, Things We Want To See, USA, 2004, 7 min

An introspective work that obliquely measures the fragility of life against boundless forces of nature, such as Alaskan ice floes, the Aurora Borealis and magnetic storms.

Peter Kubelka, Dichtung Und Wahrheit, Austria, 2003, 13 min

In cinema, as in anthropological study, the ready-made can reveal some of the fundamental ‘poetry and truth’ of our lives. Kubelka has unearthed sequences of discarded takes from advertising and presents them, almost untouched, as documents that unwittingly offer valuable and humorous insights into the human condition.

Morgan Fisher, ( ), USA, 2003, 21 min

‘I wanted to make a film out of nothing but inserts, or shots that were close enough to being inserts, as a way of making them visible, to release them from their self-effacing performance of drudge-work, to free them from their servitude to story.’ (Morgan Fisher)

Ichiro Sueoka, T:O:U:C:H:O:F:E:V:I:L, Japan, 2003, 5 min

Like Fisher’s film, Sueoka’s video also uses cutaways, but this time the shots are from 60s spy dramas, and retain their soundtracks. Stroboscopically cut together, it becomes a strange brew, like mixing The Man from U.N.C.L.E with Paul Sharits’ T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G.

Bruce Conner, Luke, USA, 2004, 22 min

In 1967 Bruce Conner visited Dennis Hopper, Paul Newman and others on the set of Cool Hand Luke and shot a rarely seen roll of silent 8mm film of the production. Almost forty years later, he has returned to this footage and presents it at three frames per second, creating an almost elegiac record of that time. Patrick Gleeson, Conner’s collaborator on several previous films, has prepared an original soundtrack for this new work.

PROGRAMME NOTES

POETRY AND TRUTH

Saturday 30 October 2004, at 9pm

London BFI Southbank NFT3

ENID’S IDYLL

Larry Jordan, USA, 2004, 16mm, b/w, sound, 17 min

I have used 46 engraved Doré illustrations to “Idylls of the King” as settings for his extravagantly romantic saga. As Enid, the protagonist, is seen in a vast array of scenes from deep forests to castle keeps, her champion is sometimes with her, sometimes away fighting archetypal foes. She dies and, through the magic of Gustav Mahler’s resurrection symphony, lives again. (Larry Jordan)

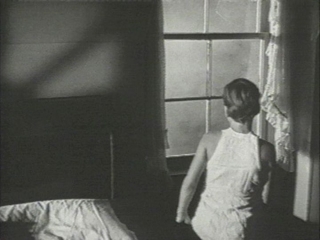

I BEGAN TO WISH

Julie Murray, USA, 2003, 16mm, colour, silent, 5 min

The sea sucks the seed back into the ocean, the flowers fold like umbrellas, shoots recoil into hiding, in seeds that shrink. The plants accelerate their tremble and wobble and glass unbreaks all around them. Strawberries blanch and tomatoes grow pale. The father, leering, holds forth a flower and suddenly his smile fades to awful seriousness. In an odd concentrated ritual the father and son carefully tip over all the flower pots, laying the plants to rest and it is in this end, around the time he figures the flowers are talking to him, that the son wishes his father had killed him. (Julie Murray)

THINGS WE WANT TO SEE

Rebecca Meyers, USA, 2004, 16mm, colour, sound, 7 min

A visit to a place they had seen many times, but wouldn’t again. Just before we left, the northern lights, which she tells me she had always wanted to see (waking in the early hours and waiting), hinted in the sky. Months after she was gone, I heard this recording for the first time. (Rebecca Meyers)

DICHTUNG UND WAHRHEIT

Peter Kubelka, Austria, 2003, 35mm, colour, silent, 13 min

Poetry and Truth was originally presented, albeit in a different format, during one of the “What Is Film” lectures at the Austrian Film Museum in Vienna, in this case on the subject of ‘acting and being’. In addition to screening a behind the scenes reel filmed on the set of The Misfits, Kubelka showed 13-minutes of footage shot by unidentified cameramen for a number of TV commercials made by an Austrian production company. Given that his one-minute masterpiece, Schwechater (1958), began life as a commission for a beer commercial, it would appear that his imagination had once again been aroused by the phantom world of advertising. While assembling the footage for demonstration purposes, the filmmaker succumbed to the impulse to also make the images speak with their own strange and beautiful logic. It would be misleading to call Poetry and Truth a ‘found’ film. Its footage has been gathered, selected, and edited together at very specific junctures to produce an archival, pedagogical, and yet weirdly electrifying collection of ethnographic camera ‘views’. But instead of recording an unknown tribe’s way of life in the wilderness, this ethnography bears witness to certain of our own Western rituals – namely “make believe,” “you should own,” and “go and buy.” Following his ‘metric’ and ‘metaphoric’ film phases, the latter exemplified by Unsere Afrikareise (1966), Kubelka now submits a new type of cinema for our consideration: the ‘metaphysical’ film. Metaphysical in the sense that, for the first time in his career, Kubelka allows the medium’s materiality (i.e., what film physically consists of) to recede, and instead foregrounds cinema’s magical capacity to locate and record anthropological rules, rituals, and myths in the unlikeliest of places. Poetry and Truth features twelve such ‘stories’; twelve sequences, each composed of one shot that is repeated in three, or five, or a dozen variations. Each take captures a movement from a stasis to motion and back again. For Kubelka, the repetition of physical movement – as in dance, as in film, as in life – is the fundamental law of the universe, from which even civilisation’s most complex systems derive. The act of conveying this principle via the ‘truth’ (the camera originals) of commercials is certainly a form of ‘poetry’ – but that’s not the source of the film’s title. At some point in each of these takes, the divine light of illusion falls upon people, dogs, buckets, and pasta. These simple truths’ are abruptly transformed into actors of ‘poetry’, and then, just as suddenly, fall back into their original non-poetic selves. As archaeologist and archivist, Kubelka is dutifully passing these telling artefacts on to the researchers of future generations. It’s easy to see why Kubelka doesn’t want Poetry and Truth to be thought of as a critique of advertising. He’s after something more essential and isn’t interested in using his work to express trivial opinions about some aspect of modern life. He’d rather champion the joy of rhythm, the joy of life, and affirm the cyclical nature of human endeavour – even if it means affirming and preserving the remnants of a trivial economy in the process. (Alexander Horwath, Film Comment)

( )

Morgan Fisher, USA, 2003, 16mm, colour, silent, 21 min

The origin of ( ) was my fascination with inserts. Inserts are a crucial kind of shot in the syntax of narrative films. Inserts show newspaper headlines, letters, and similar sorts of significant details that have to be included for the sake of clarity in telling the story. I have long been struck by a quality of inserts that can be called the alien, and as well the alienated. Narrative films depend on inserts (it’s a very rare film that has none), but at the same time they are utterly marginal. Inserts are far from the traffic in faces and bodies that are the heart of narrative films. Inserts have the power of the indispensable, but in the register of bathos. Inserts are above all instrumental. They have a job to do, and they do it; and they do little, if anything, else. Sometimes inserts are remarkably beautiful, but this beauty is usually hard to see because the only thing that registers is the news, the expository information, that the insert conveys. That’s the unhappy ideal of the insert: you see only what it does, and not what it is. This of course is no more than the ideal of all the instruments of narrative filmmaking and the rules that govern their use. A rule, or a method, underlies ( ), and I have obeyed it, even if the rule and my obedience to it are not visible. I needed the rule to make the film; it is not necessary for you to know what it is. A rule has the power of prediction, but only if you see it. To the extent that the rule remains invisible, the unfolding of the film is, for better or worse, difficult to foresee. The important thing is what the rule does. No two shots from the same film appear in succession. Every cut is a cut to another film. There is interweaving, but it is not the interweaving of dramatic construction, where intention and counter-intention are composed in relation to each other to produce friction that culminates in a climax. Instead it is an interweaving according to a rule that assigns the shots as I found them to their places in an order. In keeping with my wish to locate ( ) as far as possible from the usual conventions of cutting, whether those of montage or those of story films, the rule that puts the shots in the order has nothing to do with what is happening in them. I wanted to free the inserts from their stories, I wanted them to have as much autonomy as they could. I thought that discontinuity, cutting from one film to another, was the best way to do this. It is narrative that creates the need for an insert, assigns an insert to its place and keeps it there. The less the sense of narrative, the greater the freedom each insert would have. But of course any succession of shots, no matter how disparate, brings into play the principles of montage. That cannot be helped. Where there is juxtaposition we assume specific intention and so look for meaning. Even if there is no specific intention, and here there is none, we still look for meaning, some way of understanding the juxtapositions. At each cut I intended only discontinuity, cutting from one film to another, but beyond that nothing more. Indeed, beyond that simple device I could not intend any specific meaning, because whatever happens at each cut is the consequence of whatever two shots the rule put together, and the rule does not know what is in the shots. So what happens specifically at each cut is a matter of chance. (Morgan Fisher)

T:O:U:C:H:O:F:E:V:I:L

Ichiro Sueoka, Japan, 2003, video, colour, sound, 5 min

This is part of the “Requiem for Avant-Garde Film” series. (An example of minimal film for re-reading of Structural Films.) The concept of this work was combined with Paul Sharits’ film, T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G (1968) and the cliché of the Hollywood cinema, especially, crime suspense thrillers. And the title was extracted from Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1957). We could often see the depiction of a close-up hand in cinema, and we may find out that hand was a criminal’s hand. And a flicker was used to signify a crime. That is to say, in a cinema, a hand and flicker are the codes that make the representation of ‘evil’. (Ichiro Sueoka)

LUKE

Bruce Conner, USA, 2004, video, colour, sound, 22 min

Luke is a poetic film document created entirely by Bruce Conner in 1967 during one day of the production of Cool Hand Luke on location near Stockton, California on a country road. The main subject of the film is the Cool Hand Luke production apparatus and the people working behind the camera. The scene being photographed for their movie is a sequence with about 15 shirtless convicts working at the side of a hot black tar road with shovels. Sand is tossed on the road until it is covered. Then they move farther down the road. Shotgun carrying guards oversee their work at all times. The set itself has a representation of military and police officers as well as a highway motorcycle policeman. The actors (Paul Newman, Dennis Hopper, Harry Dean Stanton, George Kennedy etc.) are seen in front and behind the camera that is shooting the movie. The event becomes a stop and go parade since the entire crew and equipment must also be moved down the road to continue filming the continuity of dialogue and action. The final shot is a view of the actors moving their shovels as if they are tossing the sand on the road but the shovels are empty. The original running time for the regular 8mm film would be about 2.5 minutes. The final digital edit of the film to tape transfer in 2004 (with original music by Patrick Gleeson) is longer because each picture frame last one third of a second: there are 3 images per second. It has the character of both a motion picture and a series of still photos. The filming with the hand-held camera created immediate edits in the camera with regular 8mm speed (18 frames per second) as well as one frame at a time. (Bruce Conner)

Back to top

Date: 31 October 2004 | Season: London Film Festival 2004 | Tags: London Film Festival

LOS ANGELES PLAYS ITSELF

Sunday 31 October 2004, at 12pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

Thom Andersen, Los Angeles Plays Itself, USA, 2003, 169 min

A remarkable documentary about cinema, an endlessly fascinating visual lecture and an important social commentary, Thom Andersen’s love letter to Los Angeles explores the city’s representation on film. With its relentless, mesmerising montage of clips and archive footage, the film explores how the Western centre of the film industry is actually portrayed on-screen. Divided into chapters that treat Los Angeles as – amongst other things – background, character and subject, the film revisits crucial landmarks (the steps up which Laurel & Hardy attempted to manoeuvre a piano in The Music Box, explores famous buildings (the Spanish Revival house in Double Indemnity, the cavernous Bradbury Building made famous by Blade Runner), and charts the city’s ‘secret’ history through such films as Chinatown, L.A. Confidential and Who Framed Roger Rabbit. As comfortable with softcore exploitation as it is with the avant-garde, Los Angeles Plays Itself is a cinematic treasure trove that makes one think again about a city that – as a movie location – has never seemed quite as romantic or exciting as New York. Indeed, the world around you may seem more mysterious and compelling after almost three hours well spent in Andersen’s company. And you’ll definitely never refer to Los Angeles as ‘L.A.’ again. (David Cox)

Also Screening: Thursday 28 October 2004, at 8:15pm London NFT1

PROGRAMME NOTES

LOS ANGELES PLAYS ITSELF

Sunday 31 October 2004, at 12pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

LOS ANGELES PLAYS ITSELF

Thom Andersen, USA, 2003, video, colour, sound, 169 min

Most movies are intended to transform documentary into fiction; Thom Andersen’s heady and provocative Los Angeles Plays Itself has the opposite agenda. This nearly three-hour “city symphony in reverse” analyses the way that Los Angeles has been represented in the movies.

Andersen, who teaches at Cal Arts, is the author of two previous, highly original film-historical documentaries – Eadweard Muybridge, Zoopraxographer and Red Hollywood (made with theoretician Noël Burch). A manifesto as well as a monument, Los Angeles Plays Itself has its origins in a clip lecture that Andersen originally “intended for locals only,” but as finished, it is an essay in film form with near-universal interest and a remarkable degree of synthesis. If Andersen’s dense montage and noirish, world-weary voice-over owe a bit to Mark Rappaport’s VCRchaeological digs, his methodology recalls the literary chapters in Mike Davis’s Los Angeles books City of Quartz and Ecology of Fear; no less than Pat O’Neill in The Decay of Fiction, but in a completely different fashion, he has found a way to turn Hollywood history to his own ends.

Digressive if not quite free-associational in his narrative, Andersen begins by detailing the effect that Hollywood has had on the world’s most photographed city – a metropolis where motels or McDonald’s might be constructed to serve as sets and “a place can become a historic landmark because it was once a movie location.” Andersen is steeped in Los Angeles architecture as well as motion pictures, and his thinking is habitually dialectical – the Spanish Revival house in Double Indemnity, which Andersen admires, turns up as another sort of signifier in L.A. Confidential, the movie that inspired his critique (not least because Andersen has the same irritated disdain for the nickname “L.A.” that San Franciscans have for “Frisco”).

With a complex nostalgia for the old Los Angeles and a far-ranging knowledge of its indigenous cinema, Andersen draws on avant-garde and exploitation films as well as studio products. In his first section, “The City as Background,” he wonders why the city’s modern architecture is typically associated with gangsters. (Producers may actually live in these houses, but, as is often the case in Hollywood, “conventional ideology trumps personal conviction.”) Andersen ponders the guilty pleasure of destroying Los Angeles, but he’s most fond of those “literalist” films that preserve, however inadvertently, or at least recognise the city’s geography: Kiss Me Deadly (with its extensive shooting in lost Bunker Hill) and Rebel Without a Cause (in which locations are shot as though they were studio sets).

Andersen goes on to discuss Los Angeles as a “character,” beginning with the city’s transformation, by hard-boiled novelists Raymond Chandler and James M. Cain, into “the world capital of adultery and murder.” The movie’s latter half is devoted to Los Angeles as subject, starting with the self-conscious urban legend of Chinatown and considering other movies – Who Framed Roger Rabbit, L. A. Confidential – that provide the city’s imaginary secret history. A disquisition on the on-screen evolution of Los Angeles cops in the 1990s leads Andersen to the African American filmmakers Charles Burnett and Billy Woodberry, who, in their neo-neorealism, provide the antithesis of movie mystification and studio fakery.

(Jim Hoberman, Village Voice)

Back to top

Date: 31 October 2004 | Season: London Film Festival 2004 | Tags: London Film Festival

NATHANIEL DORSKY: DEVOTIONAL CINEMA

Sunday 31 October 2004, at 4pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

A LECTURE SCREENING

As an antidote to the frenetic pace and complexity of modern life, Nathaniel Dorsky’s films invite an audience to connect at a precious level of intimacy, nourishing both mind and spirit. His camera is drawn towards those transient moments of wonder that often pass unnoticed in daily life: jewelled refractions of sunlight on water, dappled shadows cast along the ground.

The films are photographed, non-narrative and have none of the visual trickery we might associate with the avant-garde. Dorsky’s work achieves a sensitive balance between humanity, nature and the ethereal, weaving together lyrical statements in a rhythmic cadence that creates space for private reflection. The world floods through the lens, onto the screen and into our minds.

In this lecture-screening of Variations (which provided the inspiration for the ‘most beautiful image’ sequence of American Beauty) and his new film Threnody, Dorsky discusses the qualities of cinema that attracted him to use the medium in such a poetic way, and will read from his recently published book ‘Devotional Cinema’. This is his first public appearance in the UK.

Nathaniel Dorsky, Variations, USA, 1992-98, 24 min

Nathaniel Dorsky, Threnody, USA, 2004, 20 min

PROGRAMME NOTES

NATHANIEL DORSKY: DEVOTIONAL CINEMA

As an antidote to the frenetic pace and complexity of modern life, Nathaniel Dorsky’s films invite an audience to connect at a precious level of intimacy, nourishing the mind and spirit. With films assembled in an almost selfless way, the viewer is given the freedom to express oneself more fully, rather than be consciously absorbed in the projections of another person. ‘In these films the audience is the central character and, hopefully, the screen your best friend.’

The films are photographed, non-narrative and have none of the visual trickery we might associate with the ‘avant-garde’. Dorsky’s camera is drawn towards those transient moments of wonder that often pass unnoticed in daily life: the jewelled refraction of sunlight on water, reflections from windows and dappled shadows cast along the ground. His iridescent cinematography is arranged in carefully montaged phrases that remain entirely open to the viewer’s personal interpretation; no heavily coded meanings and subtexts are imposed through associations in the editing. The world floods through the lens, onto the screen and into our minds.

Dorsky approaches each film as though it is a song, weaving together lyrical statements in a rhythmic cadence. His work achieves a sensitive balance between humanity, nature and the ethereal, creating space for private reflection. To accompany this screening of Variations and his new film Threnody, Nathaniel Dorsky will discuss the aspects of cinema that attracted him to use the medium in such a poetic way, to explore the inexpressible qualities of human life, and read from his recently published book ‘Devotional Cinema’. Though his work has been screened at major international museums, festivals and cinematheques, this is his first public appearance in the UK.

Nathaniel Dorsky lives in San Francisco, where he makes a living as a professional ‘film doctor’, editing documentaries that often appear on American public television and the festival circuit. In 1967 he won an Emmy award for his photographic work on the CBS production ‘Gaugin in Tahiti: Search for Paradise’. He has been making personal films since 1964, and his works are in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art (New York), Pacific Film Archives (Berkeley), Image Forum (Tokyo) and Centre Georges Pompidou (Paris). It is widely acknowledged that the ‘most beautiful image’ sequence – a plastic bag floating in the wind – from the Oscar winning feature American Beauty was directly inspired by a similar shot from Dorsky’s film Variations.

(Mark Webber)

VARIATIONS

Nathaniel Dorsky, USA, 1992-98, 16mm, colour, silent, 24 min

‘What tender chaos, what current of luminous rhymes might cinema reveal unbridled from the daytime word? During the Bronze Age a variety of sanctuaries were built for curative purposes. One of the principal activities was transformative sleep. This montage speaks to that tradition.’ (Nathaniel Dorsky)

THRENODY

Nathaniel Dorsky, USA, 2004, 16mm, colour, silent, 20 min

‘Threnody is the second of two devotional songs, the first being The Visitation. It is an offering to a friend who has died.’ (Nathaniel Dorsky)

Back to top

Date: 31 October 2004 | Season: London Film Festival 2004 | Tags: London Film Festival

THROW YOUR WATCH TO THE WATER

Sunday 31 October 2004, at 7pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

Eugeni Bonet, Tira Tu Reloj al Agua (Throw Your Watch to the Water), Spain, 2004, 91 min

José Val del Omar (1904-82), one of the pioneers of European avant-garde film, remains virtually unknown outside of Spain. His visionary Triptico Elemental de España (1953-61) embodies the soul, landscape and diverse cultural mix of his Andalucian homeland, connecting life on our planet with the elementary forces of the universe. Using material shot by the film-maker between 1968-82, Eugeni Bonet has assembled Throw Your Watch to the Water, whose images, ranging from documentary to complete abstraction, mark the passage from the earthly world to a transcendental plane. The film opens in the Alhambra, detailing the intricate Moorish architecture, pulsing fountains and activities of the local people. The ancient citadel, at first serene and regal, is overrun by the transparent bodies of tourists, whilst the ‘videoterrorifico mirror’ of television reflects the frenzy of modern media. Val del Omar envisaged a ‘cinematic vibration’ that would be the vertex of his life’s work, and this film, in which images and thoughts flow free of time, is a meta-mystical allegory that seeks a unity between the spiritual realm, the ancient world and contemporary life.

Also Screening: Saturday 30 October 2004, at 8:30pm, London ICA2

PROGRAMME NOTES

THROW YOUR WATCH TO THE WATER

Sunday 31 October 2004, at 7pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

TIRA TU RELOJ AL AGUA (THROW YOUR WATCH TO THE WATER)

Eugeni Bonet, Spain, 2004, 35mm, colour, sound, 91 min

Despite a circle of admirers that includes the directors Chris Marker and Victor Erice, José Val del Omar (1904-1982), one of the pioneers of European avant-garde film, remains virtually unknown. In pursuing his dream for a cinema for all the senses he made numerous technical innovations and discoveries, and patented designs for cinematic surround sound, wide-screen projection and special lenses years before they became commonplace.

His career began in the 1920s with dozens of ethnographic films made for the Misiones Pedagógicas. Focusing on the impoverished regions of Spain, the surviving examples are reminiscent of the stark, early documentaries of Luis Buñuel.

Throughout the 1950s he worked on the Triptico Elemental de España, consisting of three short 35mm films that each characterised one of the elements: water (Aguaespejo granadino, 1953-55), fire (Fuego en Castilla, 1958-60) and earth (Acariño galaico, 1961). Val del Omar was fundamentally connected to the soul, landscape and culture of his Andalucian homeland, and these films embody its diverse cultural history, referencing Christian and Islamic beliefs, and the connections between life on our planet and the universal whole. There are some similarities with the trance films of Anger, Brahage, Deren and Markopoulos, though Val del Omar’s methods are overtly mystical and cosmic. Throw Your Watch to the Water has been assembled by Eugeni Bonet, working with the Archivo María José Val del Omar and Gonzalo Sáenz de Buruaga, to realise a work that occupied the film-maker for decades up until his sudden death in a car accident.

The film is set in Granada, an extraordinary location where east meets west. It opens with footage of the Alhambra and its surroundings, detailing the extraordinary Moorish architecture and intricate decoration, the pulsing water of its fountains and the activities of the local people. The ancient citadel, shown at first serene and regal, is later overrun by the transparent bodies of tourists, while the ‘videoterrorifico mirror’ of television reflects the frenzy of modern media.

These ‘variations on an intuited cinegraphy’ have been created entirely from material shot by Val del Omar between 1968-82. The newly commissioned atmospheric score is punctuated by his poetic declarations which invite comparison with both Federico García Lorca and Sun Ra.

Val del Omar envisaged a “cinematic vibration” that would be the vertex of his life’s work, a development and elaboration of the ‘Elementary Triptych’ in which he first presented his radical cinematic visions. The passage of images, which ranges from documentary to complete abstraction, is exquisitely photographed in lush colours and tonal monochromes. Delirious visual sequences mark the passage from the earthly world to a transcendental plane. The film is a meta-mystical allegory of life, death and rebirth led by the elementary forces of the universe, seeking unity between the spiritual realm, the ancient world and contemporary life, where images and thoughts flow free of time.

(Mark Webber)

Back to top