Date: 26 May 2002 | Season: Shoot Shoot Shoot 2002 | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

DIVERSIFICATIONS

Sunday 26 May 2002, at 3pm

London Tate Modern

From personal montage through to exploration of the cinematic process, the work was sensuous and playful. As a creative group, the Co-op covered vital aesthetic ground and resisted categorisation. This programme does not pursue a single theme or concept, rather it demonstrates the broad range of work that was produced during this time.

The exposition section of Annabel Nicolson’s Shapes reveals its tactile evolution, as visible dirt is made evident by the step-printing technique. Moving into real time, the multiple layers of superimposition present strange spatial dimensions as the filmmaker toys with light, moving among the paper structures in her room. Footsteps engages the camera (viewer) in a playful game of “statues”. The film was often presented as a live performance in which Marilyn Halford crept up on her own projected likeness. Le Grice’s Talla adopts an almost mythical pose. Images slowly encroach on the frame as the visual tension rises, later to explode in spectacularly bending, twisting single-frame bursts. The brief, rapid-fire collage White Lite by Jeff Keen is made up of baffling layers of live action, stop-motion, obliteration and assemblage. Anne Rees-Mogg’s Muybridge Film, in homage to the pioneer of motion photography, constructs a playful film by breaking down a sequence into its constituent frames. Moment is an unmediated look, erotic but not explicit, as saturated as its celluloid. It’s a key work of Dwoskin’s early sensual portraits of solitary girls, in which the returning stare challenges our objective / subjective gaze. Chris Welsby’s Windmill II is one of a series in which propeller blades rotate in front of the camera, acting as a second shutter, controlled by an unpredictable and natural force. In this instance, the blades are backed with a reflective material that offers a glance back at the recording device intermittent with the zoetropic view of the park. In The Girl Chewing Gum, by John Smith, the narration appears to direct everyday life before breaking down, causing the viewer to question the accepted relationship between sound and image, the suggestive power of language. Chinese images and slogans are transformed by split-screen, ingrained dirt and hand-held photography to create a visual pun in Ian Kerr’s film, from “Persisting in our struggle” to Persisting in our vision.

Annabel Nicolson, Shapes, 1970, colour, silent, 7 min (18fps)

Marilyn Halford, Footsteps, 1974, b/w, sound, 6 min

Malcolm Le Grice, Talla, 1968, b/w, silent, 20 min

Jeff Keen, White Lite, 1968, b/w, silent, 2.5 min

Anne Rees-Mogg, Muybridge Film, 1975, b/w, silent, 5 min

Stephen Dwoskin, Moment, 1968, colour, sound, 12 min

Chris Welsby, Windmill II, 1973, colour, sound, 10 min

John Smith, The Girl Chewing Gum, 1976, b/w, sound, 12 min

Ian Kerr, Persisting, 1975, colour, sound, 10 min

Screening introduced by Marilyn Halford

PROGRAMME NOTES

DIVERSIFICATIONS

Sunday 26 May 2002, at 3pm

London Tate Modern

SHAPES

Annabel Nicolson, 1970, colour, silent, 7 min (18fps)

“I tried to make a kind of environment in the room where I lived in Kentish Town and to make a film within it. There were pieces of paper and screwed up, transparent gels hanging from the ceiling; it was quite dense in some parts. I wandered through it with a camera and then other parts were filmed on the rooftop at St Martins. I think I was just very much trying to find my way in a whole new area of work. I remember it involved a lot of re-filming, which was the part I liked. The process was very fluid, similar to painting. I got quite interested in the specks of dust and dirt on the film and the re-filming gave me a chance to look at that more closely. Probably the thing that attracted me to film was the light … the kind of floating quality you can get, images suspended in light. Looking at it now, the kind of paintings I was doing before were floating shapes. It seems to me that the kind of things I was looking for I should be able to do with film. When I make a film, I’m not sure what I’m ever trying to achieve … it kind of gets clearer to me as I’m doing it.” —Annabel Nicolson, interview with Mark Webber, 2002

“Compassion; care; love; appreciation; attention. Quietude; silence; slowness; gentleness; subtlety; lyricism; beauty. It is terms like these that Annabel Nicolson’s films can be discussed in (exploratory would be another), if they are to be discussed at all; and perhaps they are best left to themselves, and to the receptive eye, mind, and soul of the viewer. They are humble, unpretentious, searching, and thoughtful films: they are reverent, after a style, and should be seen with a similar sort of reverence. The ephemeral thing, by this compassionate attention, is given the aspect of timelessness which transcends mere nostalgia: the thing is seen ‘under the aspect of eternity’.” —David Miller, Paragraphs On Some Films by Annabel Nicolson Seen in March 1973

FOOTSTEPS

Marilyn Halford, 1974, b/w, sound, 6 min

“Footsteps is in the manner of a game reinacted, the game in making was between the camera and actor, the actor and cameraman, and one hundred feet of film. The film became expanded into positive and negative to change balances within it; black for perspective, then black to shadow the screen and make paradoxes with the idea of acting, and the act of seeing the screen. The music sets a mood then turns a space, remembers the positive then silences the flatness of the negative. I am interested in the relationship of theatrical devices in film working at tangents with its abstract visual qualities. The use of a game works the memory, anticipation is set, positive film stands to resemble a three-dimensional sense of time in past/future. Then negative holds out film itself as the image is one stage further abstracted and a disquiet is set up in the point that the sound track ends, whilst the picture track continues.” —Marilyn Halford, Perspectives on British Avant-Garde Film exhibition catalogue, 1977

“We’d just got one of these Russian film developing tanks, that you can load 100 feet of black and white film into and develop it yourself, which is very appealing because it means you haven’t got all the palaver of going to labs. Footsteps is based, obviously, on a game. Now whose early work would I have seen that prompted that? I think the image itself came from René Clair. That slightly rough black and white image I like very much – the idea of it not mattering if it’s got speckly and dusty. It had a certain degree of antiquity built into it which, to me, was quite liberating because it’s hard to keep it all dust free and so forth. Anyway, that’s how I wanted it, I wanted it to look old even before it started, like old footage. Consequently it’s got the Scott Joplin soundtrack, “The Entertainer”; just because it’s amusing and also to add that aged thing to it. The first time it goes through it’s in negative so you wouldn’t necessarily see what was going on, so you would have a lot of questions and curiosity as to what was happening. And then when all is revealed the right way round, it is just so simple, it’s just such a simple game. I suppose the performance part of it just grew out of that, to extend it really, it was another way of presenting it – to take part and to play the game with the film image itself.” —Marilyn Halford, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

TALLA

Malcolm Le Grice, 1968, b/w, silent, 20 min

“Talla is the most narrative/subjective film I have yet made. Because all the material was shot by me in a week or so it has location continuity, which becomes very important in the film. The pace of the cutting is still fast and images still work from perception to conception or perhaps in this film – to ‘feeling’. However, there is no consistent building up of pace and the fast-cut pieces are held within pauses so that there are often ‘clusters’ of images diving out of a mainly calm field.” —Malcolm Le Grice, Interfunktionen 4, March 1970

“I think Talla is a hard film for most people. It’s a very psychological and mysterious film. It starts out, in one primitive way, from the interplay of the black and the white. I was interested in this white screen on which things appear black. It’s highly orchestrated, in terms of the black and white qualities of the image. There’s something that’s coming out in this work, in the mythological kind of subject – Chronos Fragmented and the Cyclops and all of that stuff – that Talla is playing on. The shot material is actually on a very obscure bit of Dartmoor, and Dartmoor Prison and the warders there. So there’s that element of the threatening, mysterious bit of society which is something that you can’t get into, the dark side of the social. It’s also very mythical, in that the gods and ghosts of that landscape are floating around there in the mist. It was completely edited directly on 16mm using a magnifying glass, I didn’t edit it at all through a viewer. I thought of it symphonically, in terms of the lengths and orchestration. There’s an element of propheticness in there…” —Malcolm Le Grice, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

WHITE LITE

Jeff Keen, 1968, b/w, silent, 2.5 min

“Watch the ghost of Bela Lugosi decay before your very eyes. A sequel to Plan 9 From Outer Space.” —Jeff Keen/Deke Dusinberre, “Interim Jeff Keen Filmography with Arbitrary Annotations”, Afterimage No. 6, 1976

“Keen is indebted to the Surrealist tradition for many of his central concerns: his passion for instability, his sense of le merveilleux, his fondness for analogies and puns, his preference for ‘lowbrow’ art over aestheticism of any kind, his dedication to collage and le hazard objectif. But this ‘continental’ facet of his work – virtually unique in this country – co-exists with various typically English characteristics, which betray other roots. The tacky glamour/True Beauty of his Family Star productions is at least as close to the end of Brighton pier as it is to Hollywood B-movies… The heroic absurdity and adult infantilism that are the mainsprings of his comedy draw on a long tradition of post-Victorian humour: not the ‘innocent’ vulgarity of music hall, but the anarchicness of The Goons and the self-lacerating ironies of the 30s clowns, complete with their undertow of melancholia.” —Tony Rayns, “Born to Kill: Mr. Soft Eliminator”, Afterimage No. 6, 1976

MUYBRIDGE FILM

Anne Rees-Mogg, 1975, b/w, silent, 5 min

“I started making films in 1966, and teaching filmmaking in 1967. Before that I had been painting and drawing and exhibiting at the Beaux Arts Gallery and other places. My first film was a painterly study of interference colours and structures of soap bubbles (Nothing is Something). At the same time I made a 16mm home movie of my nephews which was called Relations. I realized two things, one that film is not about movement, and that the figurative and narrative possibilities of the second film were what I wanted to explore. Eight years later I made the film I should have made then, a small film called Muybridge Film in which I explored all the filmic possibilities of someone turning a cartwheel.” —Anne Rees-Mogg, Arts Council Film-Makers on Tour catalogue, 1980

MOMENT

Stephen Dwoskin, 1968, colour, sound, 12 min

“Moment presents a continuous, fixed gaze by the camera at a girl’s face. The fixity, although paralleling the spectator’s position, nevertheless marks itself off as ‘different’ from our view because it refuses the complex system of movements, cuts, ‘invisible’ transitions, etc. which classic cinema developed to capture our ‘subjectivity’ and absorb it into the filmic text. In this way, the distinction between the looks of the camera at the profilmic event and of the viewer at the image is emphasized. Moreover, the sadistic components inherent in the pleasurable exercise of the ‘controlling’ gaze (a basic fact without which no cinema could exist) are returned to the viewer, as it is he/she who must construct the ‘scenario’ by combining a reading of the image (slight movements of the woman, colour changes in her face, facial expressions, etc.) with an imagined (but suggested) series of happenings off-screen. The result is a narrative: the progressive excitement of a woman who masturbates.” —Paul Willemen, Perspectives on British Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1977

“In one long take, a girl whose face we see in close-up throughout, smokes and excites herself, her eyes resting at moments on the camera as if in a supplication which is also an utterly resigned accusation of film-maker and spectator alike. Not for their curiosity, which may after all be far from devoid or reverence for the human mystery, but for a willful self-withholding which is the standard human relationship. Here are three solitudes, and the film’s climax occurs after the girl’s, in her uneasy satiety, a convulsion returning her, and us, to an accentuation of the nothing from which she fled.” —Ray Durgnat, Sexual Alienation in the Cinema, 1972

WINDMILL II

Chris Welsby, 1973, colour, sound, 10 min

“A reflexiveness using the camera shutter as a technical referent can be seen in Welsby’s Windmill II. The camera is placed in a park. The basic system involves a windmill directly in front of the camera, so that as the blades pass by the lens they act as a second shutter, as a paradigm for the first shutter. The blades are covered in melanex, a mirrored fabric. The varying speeds of the blades present the spectator with varying perceptual data which require different approaches to the image. When moving slowly, they act as a repoussoir, heightening the sense of deep space. At a moderate speed, they act as an extra shutter which fragments ‘normal’ motion, emphasizing movement within the deeper plane and critiquing the notion of ‘normality’ in cinematic motion. When moving quite fast, the blades act as abstract images superimposed on the landscape image and flattening the two planes into one. And when the blades are stopped (or almost so) a completely new space is created – not only does the new (reflected) deep space contain objects in foreground and background to affirm its depth, but these objects are seen in anamorphosis (due to the irregular surface of the melanex) which effectively re-flattens them; the variations in the mirror surface create distortions which violate (or at least call attention to) the normal function of the lens of the camera.” —Deke Dusinberre, “St. George in the Forest: The English Avant-Garde”, Afterimage No. 6, 1976

“Formalism has grown up in parallel with the development of an advanced technology. The medium of landscape film brings to organic life the language of formalism. It is a language shared by both film-makers and painters. In painting, particularly American painting of the 1950s, formalistic thinking became manifest in the dictum ‘truth to materials’, placing the emphasis on paint and canvas as the subject of the work. In film, particularly the independent work done in England, it manifests itself by emphasizing the filmic process as the subject of the work. The synthesis between these formalistic concerns of independent film and the organic quality of landscape imagery is inevitably the central issue of contemporary landscape film. It is this attempt to integrate the forms of technology with the forms found in nature which gives the art of landscape its relevance in the twentieth century.” —Chris Welsby, Perspectives on British Avant-Garde Film exhibition catalogue, 1977

THE GIRL CHEWING GUM

John Smith, 1976, b/w, sound, 12 min

“I am writing this with a black ‘Tempo’ fiber-tip pen. A few months ago, I bought fifteen of these pens for sixty pence. Unfortunately, because they are so common, other people pick them up thinking they are theirs, so I don’t have many left now. I bought the pens from a market in Kingsland Road in Hackney, about a hundred yards from where the film was shot. The film draws attention to the cinematic codes and illusions it incorporates by denying their existence, treating representation as absolute reality.” —John Smith, “Directory of Independent British Cinema”, Independent Cinema No. 1, 1978

“In relinquishing the more subtle use of voice-over in television documentary, the film draws attention to the control and directional function of that practice: imposing, judging, creating an imaginary scene from a visual trace. This ‘Big Brother’ is not only looking at you but ordering you about as the viewer’s identification shifts from the people in the street to the camera eye overlooking the scene. The resultant voyeurism takes on an uncanny aspect as the blandness of the scene (shot in black and white on a grey day in Hackney) contrasts with the near ‘magical’ control identified with the voice. The most surprising effect is the ease with which representation and description turn into phantasm through the determining power of language.” —Michael Maziere, “John Smith’s Films: Reading the Visible”, Undercut 10/11, 1984

PERSISTING

Ian Kerr, 1975, colour, sound, 10 min

“Thee gap in between, perception and awareness of perception of moment is Persisting. To put it in context, it works like this, like these. Acceleration of senses in TV culture makes for rash decisions. Momentary vision. Speed kills. Speed lies. Very fast glimpses of one image mean you learn more in a time period, in a sense speed slows down our attention. Very fast glimpses of different images mean we absorb subliminally a little of many things. Speed is speeding up our attention. So time is material. Can be manipulated. Can exist an one or more speeds simultaneously. Subject. Where is camera, is camera present. Are we aware of camera, who is being looked at, what is happening, are we learning. Is it good to expect to learn. Is there actually such a thing as a valid subject. Does it matter. To be aware is to exist on levels simultaneously trusting none as finite.” —Genesis P. Orridge, “Three Absent Guesses”, Edinburgh Film Festival programme notes, 1978

“persist vb. (intr.) 1. (often foll. by in) to continue steadfastly or obstinately despite opposition or difficulty. 2. to continue to exist or occur without interuption: the rain persisted throughout the night. bridge n. 1. A structure that spans and provides a passage over a road, railway, river, or some other obstacle. 2. Something that resembles this in shape or function: his letters provided a bridge across the centuries. subtitle n. 1. an additional subordinate title given to a literary or other work. 2. (often pl.) Also called: caption. Films. a. a written translation superimposed on a film that has foreign dialogue. b. explanatory text on a silent film. ~vb. 3. (tr.; usually passive) to provide a subtitle for. –subtitular adj. soundtrack n. 1. the recorded sound accompaniment to a film. Compare commentary (sense 2). 2. A narrow strip along the side of a spool of film, which carries the sound accompaniment … Wave Upon Wave of Wheatfield.” —Ian Kerr, 2002

Back to top

Date: 28 May 2002 | Season: Shoot Shoot Shoot 2002 | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

THE EPIC FLIGHT: MARE’S TAIL

Tuesday 28 May 2002, at 6:30pm

London Tate Modern

“From one flick of the mare’s tail came an unending stream of images out of which was crystalised the milky way. Primitive, picaresque cinema.” (David Larcher)

An extended personal odyssey which, through an accumulation of visual information, builds into a treatise on the experience of seeing. Its loose, indefinable structure explores new possibilities for perception and narrative.

David Larcher, Mare’s Tail, 1969, colour, sound, 143 min

Reinforcing the idea of the mythopoeic discourse and the historically romantic view of the artist-filmmaker, Mare’s Tail is a legend, consisting of layers of sounds and images that reveal each other over an extended period. It’s a personal vision, an aggregation of experience, memories and moments overlaid with indecipherable intonations and altered musics. The collected footage is extensively manipulated, through refilming, superimposition or direct chemical treatment. The observer may slip in and out of the film as it runs its course; it does not demand constant attention, though persistence is rewarded by experience after the full projection has been endured.

While studying at the Royal College of Art, David Larcher made a first film KO (1964-65, with soundtrack composed by Philip Glass), which was subsequently disassembled and small sections incorporated in Mare’s Tail (a recurrent practise that continues through his later works). Encouraged by contact with true independent filmmakers like Peter Whitehead and Conrad Rooks, Larcher set out on to document his own life in a quasi-autobiographical manner.

Though financed by wealthy patron Alan Power, Mare’s Tail was, in its technical fabrication, a self-sufficient project made before the Co-op had any significant workshop equipment. At times, Larcher was living in a truck, and stories of films processed in public lavatories in the Scottish Highlands do not seem far from the truth. His relationship to the Co-op has always been slightly distanced, though his lifestyle impressed and influenced many of the younger, more marginal figures.

His next film, Monkey’s Birthday (1975, six hours long), was shot over several years’ travels across the world with his entourage, and this time made full use of the Co-op processor to achieve its psychedelic effect.

Screening introduced by David Larcher.

PROGRAMME NOTES

THE EPIC FLIGHT: MARE’S TAIL

Tuesday 28 May 2002, at 6:30pm

London Tate Modern

MARE’S TAIL

David Larcher, 1969, colour, sound, 143 min

“Now you see it, now you don’t. Waiting room cinema from the mountain top to the car park, an alternative to television. The good, the bad and the indifferent. Some consider it self-indulgent but me has a duty to itself. Bring what you expect to find. Not structural but starting in the beginning from the beginning…organic…prima materia…impressionable massa confusa…out of which some original naming and ordering processes spring…they are not named, but rather nailed into the celluloid. “Please don’t expect me to answer the question I’m having a hard time not falling out of this chair” syndrome.” —David Larcher, Arts Council Film-Makers on Tour catalogue, 1980

“Mare’s Tail is an epic flight into inner space. It is a 2 and 3/4 hour visual accumulation in colour, the film-maker’s personal odyssey, which becomes the odyssey of each of us. It is a man’s life transposed into a visual realm, a realm of spirits and demons, which unravel as mystical totalities until reality fragments. Every movement begins a journey. There are spots before your eyes, as when you look at the sun that flames and burns. We look at distant moving forms and flash through them. We drift through suns; a piece of earth phases over the moon. A face, your face, his face, a face that looks and splits into shapes that form new shapes that we rediscover as tiny monolithic monuments. A profile as a full face. The moon again, the flesh, the child, the room and the waves become part of a hieroglyphic language… Mare’s Tail is an important film because it expresses life. It follows Paul Klee’s idea that a visually expressive piece adds “more spirit to the seen” and also “makes secret visions visible”. Like other serious films and works of art, it keeps on seeking and seeing, as the film-maker does, as the artist does. It follows the transience of life and nature, studying things closely, moving into vast space, coming in close again. The course it follows is profoundly real and profoundly personal: Larcher’s trip becomes our trip to experience. It cannot be watched impatiently, with expectation; it is no good looking for generalization, condensation, complication or implication.” —Stephen Dwoskin, Film Is: The International Free Cinema, 1975

“A film that is almost a life style. Long enough and big enough in scope to be able to safely include boredom, blank-screens, bad footage. The kind of film that is analogous in a symbolic way to something like the ‘stream of life’ – no one would ever criticize looking out of the window as being boring sometimes. It’s not a film – more like an event composed of the collective ideas and attempts in film of several years. Like a personal diary: humorous, wry, sad, ecstatic. Concerned with texture, with seeing and not seeing, light and darkness, even life and death. Monumental not in size alone, but in its breadth of concept. Relaxed enough to be able to let one idea run on for twenty minutes before switching to another. The exact opposite of most film-making which attempts to keep the audience ‘interested’ by rapidly changing from one form or idea to another, to exclude boredom and participation. A ‘super-Le Grice’ in that it has inherent sensitivity and humanity, as well as superlative and highly inventive technique. It opens up film-making by including such self-conscious ethics as those propounded by Warhol etc. as a natural part of the film ethic as a whole.” —Mike Dunford, Cinemantics No. 1, January 1970

“Mare’s Tail is one of the finest achievements in cinema. It is a masterpiece that everyone in the country should get to see. To write about it is about as difficult as conveying the essence of magic, the meaning of existence, the quality of love or the shadows of a receding dream. For the film is pure myth, a living organism in its own right, a creation whose infinite complexity makes criticism of it a shallow irrelevancy (or at best a crude mythology). The achievement is that the film never looks like a mere catalogue of special effects – the vision is integrated, relaxed, spontaneous and too fluid for there to be any sense of contrivance in this staggering display of inventive curiosity. The immense diversity of technique runs hand-in-hand with a sustained simplicity of treatment. You’re aware of a mind that is open and loving toward everything: and this loving openness of response transfigures every image in the film, as it eventually transfigures the viewer too…” —John Du Cane, Time Out, 1972

“A film that is undoubtedly one of the most important produced in this country and that stands comparison with the best from the United States. It’s as if it were the first film in the world. When Mare’s Tail first appeared it was compared to Brakhage’s Art of Vision, as an examination of ways of seeing. The comparison can be taken further: as Brakhage is to the New American Cinema, it seems to me, so Larcher should be considered to the New English Cinema… Mare’s Tail is not only about vision but proposes an epistemology of film, particularly in its first reel: revealing basic elements of film in an almost didactic fashion: grain, frame, strip, projector, light. We see a film in perpetual process, being put together, being formed out of these attitudes. The first reel is a ‘lexicon’ to the whole film – to film in general – holding together what is essentially an open-ended structure to which pieces could be continually added and offering us a way to read that film. It is at once a kind of autobiography and a film about making that autobiography.” —Simon Field, “The Light of the Eyes”, Art and Artists, December 1972

“Pierre Boulez came to a screening of Mare’s Tail at Robert Street once. Simon Hartog said, “Oh, I sent my father to see Mare’s Tail”, his father was an impresario for people like Joan Sutherland and Pierre Boulez, and it turned out that Boulez came and was sat behind us. I’d been living in trucks and I’d just come up and it happened to be the same day. I went along and found this old tramp called Eric – this famous character who was around in those days, early ’70s – and took him along. We were sitting there and then I suddenly realised Boulez was behind. After half an hour he said, “C’est le perfection,” and walked out with Simon’s father!” —David Larcher, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

Back to top

Date: 29 May 2002 | Season: Infinite Projection, Shoot Shoot Shoot 2002 | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

8MM FILMS FROM THE LONDON CO-OP

Wednesday 29 May 2002, at 7:30pm

London The Photographers’ Gallery

The home movie format of 8mm can empower artists to make extremely personal and direct film observations. Spontaneity and intimacy are inherent to this pocket sized system. This special evening of single and multi-screen small gauge wonders concludes Shoot Shoot Shoot, a major retrospective of British avant-garde film, which screens at Tate Modern throughout May. Many of the makers will be on hand to introduce their work.

David Crosswaite, Puddle, UK, 1968, b/w, silent, 4 min

Mike Dunford, Four Short Films, UK, 1969, b/w & colour, silent, 10 min

Mike Dunford, One Million Unemployed in Winter 1971, UK, 1971, colour, sound-on-tape, 4 min

Jeff Keen, Wail, UK, 1960, colour, silent, 5 min

Jeff Keen, Like the Time is Now, UK, 1961, colour, silent, 6 min

Malcolm Le Grice, China Tea, UK, 1965, colour, silent, 10 min

Annabel Nicolson, Black Gate, UK, 1976, colour, silent, 4 min

Sally Potter, Jerk, UK, 1969, b/w, silent, 3 min (two screen)

William Raban, Sky, UK, 1969, colour, silent, 5 min (four screen)

John Smith, Out the Back, UK, 1974, colour, silent, 4 min

David Crosswaite, Mike Dunford, Malcolm Le Grice, Sally Potter, William Raban and John Smith in attendence.

PROGRAMME NOTES

8MM FILMS FROM THE LONDON CO-OP

Wednesday 29 May 2002, at 7:30pm

London The Photographers’ Gallery

IN CELEBRATION OF 8MM

“What first attracted me to 8mm film in particular was its materiality and the way it produced tangibility problematics on all levels: the acquiring and setting up of increasingly scarce, quality projection equipment, the physicality of the sound made by the film strip running through the projector gate continuously reminds the viewer of the machine’s presence in the room, the attention to projection speed (variable fps), and the frequent act of projecting camera originals (the horror!) instead of film prints. And then there is the film itself – the sensuous texture of the projected image, the subtlety or sumptuousness of gradations in black-and-white or the discriminating use of colour, the graininess of the image (as emotionally satisfying and particular as the actual silver sparkles on 35mm nitrate stock), the unpredictability of the sound stripe, and the fragility and fleeting sense of the image’s presence on the screen. All these qualities contribute to the intimacy created between the projected films and any group able to give themselves over to the act of actually seeing.” (Jytte Jensen, Museum of Modern Art, in the exhibition catalogue “Big As Life”, 1999)

Back to top

Date: 1 June 2002 | Season: Shoot Shoot Shoot 2002 | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT: THE FIRST DECADE OF THE LONDON FILM-MAKERS’ COOPERATIVE & BRITISH AVANT-GARDE FILM 1966-76

June 2002–August 2002

International touring exhibition consisting of eight programmes of single-screen, double screen films and expanded cinema

May 2002 – London, UK – Tate Modern

June 2002 – Paris, France – Scratch Projections at Centre Wallonie Bruxelles / EOF Gallery

July 2002 – Brisbane, Australia – Brisbane International Film Festival / Institute for Modern Art

July 2002 – Melbourne, Australia – Melbourne International Film Festival / Experimenta / Gamma Space

September 2002 – Berlin, Germany – Arsenal / Deutsche Kinemathek

September 2002 – Karlsruhe, Germany – Kinemathek / Kamera Kunstverein

September 2002 – Frankfurt, Germany – Deutsches Filmmuseum

September 2002 – Bremen, Germany – Kino 46 / Hochschule für Künste

October 2002 – Hamburg, Germany – Metropolis Kino / Lichtmeß

November 2002 – Basel, Switzerland – Kunsthalle Basel / Stadtkino Basel

November 2002 – Barcelona, Spain – Fundació Antoni Tàpies / Hangar

November 2002 – Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain – ARTIUM

March 2003 – New York. USA – Anthology Film Archives / Galapagos Art Space

May 2003 – Manchester, UK – Cornerhouse

May 2003 – Gateshead, UK – BALTIC / Side Cinema

March 2004 – Athens, Greece – Deste Foundation

April 2004 –Tokyo, Japan – Image Forum Festival / Hillside Gallery

May 2004 – Kyoto, Japan – Goethe Institut Kyoto

August 2004 –Seoul, Korea – 1st Seoul Experimental Film Festival

Date: 13 October 2006 | Season: Shoot Shoot Shoot 2006 | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

NOTHING IN COMMON: 40 YEARS OF THE LONDON FILM-MAKERS’ COOP

Friday 13 October 2006, at 5pm

London Frieze Art Fair

The London Film-Makers’ Co-operative (LFMC) was established 40 years ago today, on 13 October 1966. An artist-led project, it incorporated a distribution collection, screening room and film workshop. It grew from an informal film society into one of the major international centres of avant-garde cinema and its films form the basis of the current LUX collection. Many LFMC filmmakers experimented with projection techniques, creating expanded cinema performances, installations and multi-screen films, with artists such as Malcolm Le Grice prefiguring much of contemporary practice with his remarkable body of work. In Castle One, made from scraps of footage found outside commercial film labs, a photoflood light bulb is hung directly in front of the screen and flashed intermittently during projection, bleaching out the image, illuminating the screening room and breaking down the relationship between film and audience. Gill Eatherley’s Aperture Sweep, from her ‘Light Occupations’ series of film related activities, is a double screen performance in which Eatherley, armed with a broom (amplified to be both seen and heard), appears to sweep the screen clean for future projections. Both pieces attempt a kind of erasure of the onscreen image, conceptually and physically challenging the roles of maker and spectator.

Malcolm Le Grice, Castle One, UK, 1966, 16mm/performance, 20 min

Gill Eatherley, Aperture Sweep, UK, 1973, 16mm/performance, 10 min

‘Nothing in Common’, curated by Mark Webber, is a special presentation of The Artists Cinema.

Date: 10 November 2006 | Season: Shoot Shoot Shoot 2006 | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT: BRITISH AVANT-GARDE FILM OF THE 1960s & 1970s

November 2006 – May 2008

International Touring Programme

The 1960s and 1970s were groundbreaking decades in which independent filmmakers challenged cinematic convention. In England, much of the innovation took place at the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative, an artist-led organisation that enabled filmmakers to control every aspect of the creative process. LFMC members conducted an investigation of celluloid that echoed contemporary developments in painting and sculpture. During this same period, British filmmakers also made significant innovations in the field of ‘expanded cinema’, creating multi-screen projections, film environments and live performance pieces.

The physical production of a film (its printing and processing) became integral to its form and content as Malcolm Le Grice, Lis Rhodes, Peter Gidal and others explored the material and mechanics of cinema, making radical new works that contributed to a new visual language. The London Film-Makers’ Co-operative, which was established on 13th October 1966, grew from a film society at the heart of London’s sixties counterculture to become Europe’s largest distributor of experimental cinema and was recognised internationally as a major centre for avant-garde film.

“Shoot Shoot Shoot: The First Decade of the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative & British Avant-Garde Film 1966-76” was a major research and exhibition project that toured worldwide from 2002-04. The original 8 programme package of single screen films, multiple projection works and expanded cinema performances that was shown at 19 venues including London Tate Modern, Gateshead Baltic, Basel Kunsthalle, Barcelona Fundaçio Antoní Tapies, Athens Desté Foundation, Tokyo Image Forum and the Melbourne International Film Festival.

This new package is being made available on the 40th anniversary of the LFMC to support the release of the DVD “Shoot Shoot Shoot: British Avant-Garde Film of the 1960s & 1970s” in Autumn 2006. The two programmes contain several films that are not on the DVD and some which were not included in the original tour.

10 & 11 November 2006, London Tate Modern

3 February 2007, Birmingham MAC

29 March 2007, Glasgow Transmission Gallery

25 April 2007, Osnabruck European Media Art Festival

29 May 2007, Nottingham Broadway Cinema and Media Centre (Programme 2 only)

13 & 14 June 2007, Brussels Cinémathèque royale de Belgique

25 & 30 September 2007, Zagreb 25 FPS Festival

16 October 2007, Portland Cinema Project

27 October 2007, Pittsburgh Filmmakers

8 & 9 November 2007, Rochester Visual Studies Workshop

24 & 25 November 2007, Toronto Cinematheque Ontario

29 January & 5 February 2008, Milwaukee Union Theatre

4 & 11 March 2008, Berkeley Pacific Film Archive

2 & 16 March 2008, Los Angeles Filmforum

27 & 31 May 2008, Zurich Videoex

“Shoot Shoot Shoot” is a LUX project. Curated by Mark Webber.

Date: 10 November 2006 | Season: Shoot Shoot Shoot 2006 | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT CONDENSED: PROGRAMME 1

November 2006—May 2008

International Tour

The London Film-Makers’ Co-operative was established in 1966 to support work on the margins of art and cinema. It uniquely incorporated three related activities within a single organisation – a workshop for producing new films, a distribution arm for promoting them, and its own cinema space for screenings. In this environment, Co-op members were free to explore the medium and control every stage of the process. The Materialist tendency characterised the hardcore of British filmmaking in the early 1970s. Distinguished from Structural Film, these works were primarily concerned with duration and the raw physicality of the celluloid strip.

Annabel Nicolson, Slides, 1970, colour, silent, 11 mins (18fps)

Guy Sherwin, At the Academy, 1974, b/w, sound, 5 mins

Mike Leggett, Shepherd’s Bush, 1971, b/w, sound, 15 mins

David Crosswaite, Film No. 1, 1971, colour, sound, 10 mins

Lis Rhodes, Dresden Dynamo, 1971, colour, sound, 5 mins

Chris Garratt, Versailles I & II, 1976, b/w, sound, 11 mins

Mike Dunford, Silver Surfer, 1972, b/w, sound, 15 mins

Marilyn Halford, Footsteps, 1974, b/w, sound, 6 mins

PROGRAMME NOTES

SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT CONDENSED: PROGRAMME 1

November 2006—May 2008

International Tour

SLIDES

Annabel Nicolson, 1970, colour, silent, 11 mins (18fps)

“A continuing sequence of tactile films were made in the printer from my earlier material. 35mm slides, light leaked film, sewn film, cut up to 8mm and 16mm fragments were dragged through the contact printer, directly and intuitively controlled. The films create their own fluctuating colour and form dimensions defying the passive use of ‘film as a vehicle’. The appearance of sprocket holes, frame lines etc., is less to do with the structural concept and more of a creative, plastic response to whatever is around.” (Annabel Nicolson, LFMC catalogue 1974)

AT THE ACADEMY

Guy Sherwin, 1974, b/w, sound, 5 mins

“Makes use of found footage hand printed on a simple home-made contact printer, and processed in the kitchen sink. At The Academy uses displacement of a positive and negative sandwich of the same loop. Since the printer light spills over the optical sound track area, the picture and sound undergo identical transformations.” (Guy Sherwin, LFMC catalogue 1979)

SHEPHERD’S BUSH

Mike Leggett, 1971, b/w, sound, 15 mins

“Shepherd’s Bush was a revelation. It was both true film notion and demonstrated an ingenious association with the film-process. It is the procedure and conclusion of a piece of film logic using a brilliantly simple device; the manipulation of the light source in the Film Co-op printer such that a series of transformations are effected on a loop of film material. From the start Mike Leggett adopts a relational perspective according to which it is neither the elements or the emergent whole but the relations between the elements (transformations) that become primary through the use of logical procedure.” (Roger Hammond, LFMC catalogue supplement, 1972)

FILM NO. 1

David Crosswaite, 1971, colour, sound, 10 mins

“Film No. 1 is a 10-minute loop film. The systems of super-imposed loops are mathematically inter-related in a complex manner. The starting and cut off points for each loop are not clearly exposed, but through repetitions of sequences in different colours, in different ‘material’ realities (i.e. a negative, positive, bas-relief, neg-pos overlay) yet in constant rhythm (both visually and on the soundtrack hum) one is manipulated to attempt to work out the system structure … The film deals with permutations of material, in a prescribed manner but one by no means ‘necessary’ or logical (except within the film’s own constructed system/serial.)” (Peter Gidal, LFMC catalogue 1974)

DRESDEN DYNAMO

Lis Rhodes, 1971, colour, sound, 5 mins

“This film is the result of experiments with the application of Letraset and Letratone onto clear film. It is essentially about how graphic images create their own sound by extending into that area of film which is ‘read’ by optical sound equipment. The final print has been achieved through three separate, consecutive printings from the original material, on a contact printer. Colour was added, with filters, on the final run. The film is not a sequential piece. It does not develop crescendos. It creates the illusion of spatial depth from essentially, flat, graphic, raw material.” (Tim Bruce, LFMC catalogue 1993)

VERSAILLES I & II

Chris Garratt, 1976, b/w, sound, 11 mins

”For this film I made a contact printing box, with a printing area 16mm x 185mm which enabled the printing of 24 frames of picture plus optical sound area at one time. The first part is a composition using 7 x 1-second shots of the statues of Versailles, Palace of 1000 Beauties, with accompanying soundtrack, woven according to a pre-determined sequence. Because sound and picture were printed simultaneously, the minute inconsistencies in exposure times resulted in rhythmic fluctuations of picture density and levels of sound. Two of these shots comprise the second part of the film which is framed by abstract imagery printed across the entire width of the film surface: the visible image is also the sound image.” (Chris Garratt, LFMC catalogue 1978)

SILVER SURFER

Mike Dunford, 1972, b/w, sound, 15 mins

“A surfer, filmed and shown on tv, refilmed on 8mm, and refilmed again on 16mm. Simple loop structure preceded by four minutes of a still frame of the surfer. An image on the borders of apprehension, becoming more and more abstract. The surfer surfs, never surfs anywhere, an image suspended in the light of the projector lamp. A very quiet and undramatic film, not particularly didactic. Sound: the first four minutes consists of a fog-horn, used as the basic tone for a chord played on the organ, the rest of the film uses the sound of breakers with a two second pulse and occasional bursts of musical-like sounds.” (Mike Dunford, LFMC catalogue supplement 1972)

FOOTSTEPS

Marilyn Halford, 1974, b/w, sound, 6 mins

“Footsteps is in the manner of a game re-enacted, the game in making was between the camera and actor, the actor and cameraman, and one hundred feet of film. The film became expanded into positive and negative to change balances within it; black for perspective, then black to shadow the screen and make paradoxes with the idea of acting, and the act of seeing the screen. The music sets a mood then turns a space, remembers the positive then silences the flatness of the negative.” (Marilyn Halford, LFMC catalogue 1978)

Back to top

Date: 11 November 2006 | Season: Shoot Shoot Shoot 2006 | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT CONDENSED: PROGRAMME 2

November 2006—May 2008

International Tour

The 1960s and 1970s were a defining period for artists’ film and video in which avant-garde filmmakers challenged cinematic convention. In England, much of the innovation took place at the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative, an artist-led organisation that incorporated a distribution office, projection space and film workshop. Despite the workshop’s central role in production, not all the work derives from experimentation in printing and processing. Filmmakers also used language, landscape and the human body to create less abstract works that still explore the essential properties of the film medium.

Malcolm Le Grice, Threshold, 1972, colour, sound, 10 mins

Chris Welsby, Seven Days, 1974, colour, sound, 20 mins

Peter Gidal, Key, 1968, colour, sound, 10 mins

Stephen Dwoskin, Moment, 1968, colour, sound, 12 mins

Gill Eatherley, Deck, 1971, colour, sound, 13 mins

William Raban, Colours of this Time, 1972, colour, silent, 3 mins

John Smith, Associations, 1975, colour, sound, 7 mins

PROGRAMME NOTES

SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT CONDENSED: PROGRAMME 2

November 2006—May 2008

International Tour

THRESHOLD

Malcolm Le Grice, 1972, colour, sound, 10 mins

“Le Grice no longer simply uses the printer as a reflexive mechanism, but utilises the possibilities of colour-shift and permutation of imagery as the film progresses from simplicity to complexity … With the film’s culmination in representational, photographic imagery, one would anticipate a culminating ‘richness’ of image; yet the insistent evidence of splice bars and the loop and repetition of the short piece of found footage and the conflicting superimposition of filtered loops all reiterate the work which is necessary to decipher that cinematic image.” (Deke Dusinberre, LFMC catalogue 1993)

SEVEN DAYS

Chris Welsby, 1974, colour, sound, 20 mins

“The location of this film is by a small stream on the northern slopes of Mount Carningly in southwest Wales. The seven days were shot consecutively and appear in that same order. Each day starts at the time of local sunrise and ends at the time of local sunset. One frame was taken every ten seconds throughout the film. The camera was mounted on an Equatorial Stand, which is a piece of equipment used by astronomers to track the stars. Rotating at the same speed as the earth, the camera is always pointing at either its own shadow or at the sun. Selection of image (sky or earth; sun or shadow) was controlled by the extent of cloud coverage. If the sun was out the camera was turned towards its own shadow; if it was in the camera was turned towards the sun.” (Chris Welsby, LFMC catalogue 1978)

KEY

Peter Gidal, 1968, colour, sound, 10 mins

“Slow zoom out and defocus of …” (Peter Gidal, LFMC catalogue 1974)

MOMENT

Stephen Dwoskin, 1968, colour, sound, 12 mins

“One single continuous shot of a girl’s face before, during and after an orgasm. A concentration on the subtle changes within the face – going from an objective look into a subjective one and then back out … Moment is not a woman alone, but with her ‘in person’. Have you ever really watched the face in orgasm?” (Stephen Dwoskin, Other Cinema catalogue 1972)

DECK

Gill Eatherley, 1971, colour, sound, 13 mins

“During a voyage by boat to Finland, the camera records three minutes of black and white 8mm film of a woman sitting on a bridge. The preoccupation of the film is with the base and with the transformation of this material, which was first refilmed on a screen where it was projected by multiple projectors at different speeds and then secondly amplified with colour filters, using positive and negative elements and superimposition on the London Co-op’s optical printer.” (Gill Eatherley, Light Cone catalogue, 1997)

COLOURS OF THIS TIME

William Raban, 1972, colour, silent, 3 mins

“Whilst working on previous time-lapse films, I found that colour film tended to record the actual colour of the light source rather than local colour when long time exposures were used. Using this phenomenon, Colours of this Time records all the imperceptible shifts of colour temperature in summer daylight, from first light until sunset.” (William Raban, LFMC catalogue 1974)

ASSOCIATIONS

John Smith, 1975, colour, sound, 7 mins

“Text taken from ‘Word Associations and Linguistic Theory’ by Herbert H. Clark. Images taken from magazines and colour supplements. By using the ambiguities inherent in the English language, Associations sets language against itself. Image and word work together/against each other to destroy/create meaning.” (John Smith, LFMC catalogue 1978)

Back to top

Date: 24 November 2006 | Season: Shoot Shoot Shoot 2006 | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT: DVD LAUNCH AND PERFORMANCES

Friday 24 November 2006, at 8PM

London Candid Arts Trust

A special expanded cinema performance event to mark the release of the new LUX / Re:Voir DVD “Shoot Shoot Shoot: British Avant-Garde Film of the 1960s and 1970s”.

The evening will include two performances: Guy Sherwin’s Configuration has not been performed since 1976, and William Raban’s Wave Formations will be projected for the first time in its new arrangement.

Guy Sherwin, Configuration, 1976, for 2 x Super-8 projectors and live performer, 10 min

“In this film performance a hand-held projector and a stationary projector reproduce the movements of the two cameras used in making the film. The film was made outdoors in a clearing in a wood. The filmmaker held one camera and moved in a circle around the stationary camera while recording variations of the same view. The two cameras occasionally cross each other’s path. In time we see the gradual approach of a figure towards the two cameras and her subsequent involvement in the act of filming. During the performance, the two films are projected together onto a screen. The performer holds one projector and moves in a circle around the stationary projector, echoing the original camera movements. At times, shadows of projector and projectionist are thrown upon the screen.” —Guy Sherwin, 2006

William Raban, Wave Formations, 1977-2006, for 5 x 16mm projectors, 2 x strobe lights and live performer, 25 min

“Part one: Variation in Density: The picture on each of the five screens are identical, seven second fades from black, through clear, to black again. The same fade is printed onto the optical sound track to synchronise with the picture. Then follow fades from light to dark. And from dark to light. Part Two: Intermittency: Relative patterns of occlusion and exposure occupy two screens. Each exposure fires a stroboscopic flash of colour: yellow for one screen; blue for the other, filling the centre of both screens with colour, haloed with after-image complementaries.” —William Raban, 1978

Date: 23 May 2007 | Season: Shoot Shoot Shoot 2006 | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT: EXPANDED CINEMA

Wednesday 23 May 2007, at 7PM

Wrexham Arts Centre

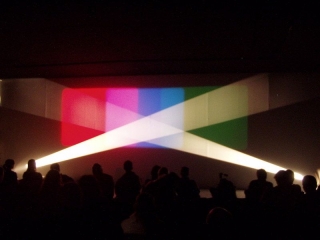

Beginning in the 1960s, artists at the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative experimented with multiple projection, live performance and film environments. In liberating cinema from traditional theatrical presentation, they broke down the barrier between screen and audience, and extended the creative act to the moment of exhibition. “Shoot Shoot Shoot” presents historic works of Expanded Cinema, for which each screening is a unique, collective experience, in stark contrast to contemporary video installations. In Line Describing a Cone, a film projected through smoke, light becomes an apparently solid, sculptural presence, whilst other works for multiple projection create dynamic relationships between images and sounds.

Malcolm Le Grice, Castle Two, 1968, b/w, sound, 32 min (2 screens)

Sally Potter, Play, 1971, b/w & colour, silent, 7 min (2 screens)

William Raban, Diagonal, 1973, colour, sound, 6 min (3 screens)

Gill Eatherley, Hand Grenade, 1971, colour, sound, 8 min (3 screens)

Lis Rhodes, Light Music, 1975-77, b/w, sound, 20 min (2 screens)

Anthony McCall, Line Describing A Cone, 1973, b/w, silent, 30 min. (1 screen, smoke)

Curated by Mark Webber. Presented in association with LUX.

PROGRAMME NOTES

SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT: EXPANDED CINEMA

Wednesday 23 May 2007, at 7PM

Wrexham Arts Centre

EXPANDED CINEMA at the LONDON FILM-MAKERS’ CO-OPERATIVE

Expanded Cinema is a term used to describe works that do not confirm to the traditional single-screen cinema format. It could mean having two (or more) images side-by-side on the screen, films that incorporate live performances or are projected in an unorthodox manner without a screen. Even light pieces that do not use any film at all. Some work demands that the filmmaker interact with the projected image, or be behind the projectors to alter their configuration throughout the screening.

The London Film-Makers’ Co-operative was an artist-led organisation formed in 1966, and uniquely incorporated a distribution office, workshop laboratory and screening room. Expanded Cinema continued the analytical exploration of the material that was conducted by filmmakers in the workshop, and emphasised the transient nature of the medium.

The Co-op’s cinema space was a flat, open room with no fixed seating. Filmmakers were free to experiment with projectors, demonstrating that the moment of exhibition can be as much a part of the work as the original concept, filming, editing and processing. The technology that puts the illusion of movement onscreen was no longer hidden away in a projection booth behind the audience, but placed amongst them.

In questioning the role of the spectator, Expanded Cinema challenged the conventions of the cinema event and introduced elements of chance and improvisation. Sometimes, what happened across the room was more important than what was up on the screen. With such work no two projections were ever the same: each screening was a unique, social, collective experience for the assembled audience.

This drive beyond the screen and theatre inevitably took the work into galleries, but only as a practical measure since open spaces and white walls were ideal for unconventional projection. The filmmakers made no attempts to commodify their work by producing editions, for many it was against their socialist principles. Though Expanded Cinema anticipated many recent trends in gallery-based moving image works and installations, there was little acceptance from the art world in the early years, or acknowledgement of this groundbreaking work today.

Mark Webber

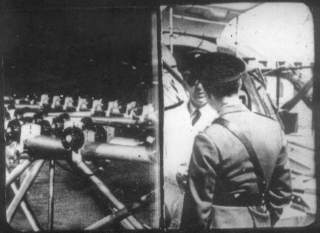

CASTLE TWO

Malcolm Le Grice, 1968, b/w, sound, 32 min (2 screens)

“This film continues the theme of the military/industrial complex and its psychological impact upon the individual that I began with Castle One. Like Castle One, much use is made of newsreel montage, although with entirely different material. The film is more evidently thematic, but still relies on formal devices – building up to a fast barrage of images (the two screens further split – to give 4 separate images at once for one sequence). The images repeat themselves in different sequential relationships and certain key images emerge both in the soundtrack and the visual. The alienation of the viewer’s involvement does not occur as often in this film as in Castle One, but the concern with the viewer’s experience of his present location still determines the structure of certain passages in the film.” —Malcolm Le Grice, London Film-Makers’ Co-operative catalogue, 1968

“Le Grice’s work induces the observer to participate by making him reflect critically not only on the formal properties of film but also on the complex ways in which he perceives that film within the limitations of the environment of its projection and the limitations created by his own past experience. A useful formulation of how this sort of feedback occurs is contained in the notion of ‘perceptual thresholds’. Briefly, a perceptual threshold is demarcation point between what is consciously and what is pre-consciously perceived. The threshold at which one is able to become conscious of external stimuli is a variable that depends on the speed with which the information is being projected, the emotional charge it contains and the general context within which that information is presented. This explains Le Grice’s continuing use of devices such as subliminal flicker and the looped repetition of sequences in a staggered series of changing relationships.” —John Du Cane, Time Out, 1977

PLAY

Sally Potter, 1971, b/w & colour, silent, 7 min (2 screens)

“In Play, Potter filmed six children – actually, three pairs of twins – as they play on a sidewalk, using two cameras mounted so that they recorded two contiguous spaces of the sidewalk. When Play is screened, two projectors present the two images side by side, recreating the original sidewalk space, but, of course, with the interruption of the right frame line of the left image and the left frame line of the right image – that is, so that the sidewalk space is divided into two filmic spaces. The cinematic division of the original space is emphasized by the fact that the left image was filmed in color, the right image in black and white. Indeed, the division is so obvious that when the children suddenly move from one space to the other, ‘through’ the frame lines, their originally continuous movement is transformed into cinematic magic.” —Scott MacDonald, A Critical Cinema 3, 1998)

“To be frank, I always felt like a loner, an outsider. I never felt part of a community of filmmakers. I was often the only female, or one of few, which didn’t help. I didn’t have a buddy thing going, which most of the men did. They also had rather different concerns, more hard-edged structural concerns … I was probably more eclectic in my taste than many of the English structural filmmakers, who took an absolute prescriptive position on film. Most of them had gone to Oxford or Cambridge or some other university and were terribly theoretical. I left school at fifteen. I was more the hand-on artist and less the academic. The overriding memory of those early years is of making things on the kitchen table by myself…” —Sally Potter interviewed by Scott MacDonald, A Critical Cinema 3, 1998

DIAGONAL

William Raban, 1973, colour, sound, 6 min (3 screens)

“Diagonal is a film for three projectors, though the diagonally arranged projector beams need not be contained within a single flat screen area. This film works well in a conventional film theatre when the top left screen spills over the ceiling and the bottom right projects down over the audience. It is the same image on all three projectors, a double-exposed flickering rectangle of the projector gate sliding diagonally into and out of frame. Focus is on the projector shutter, hence the flicker. This film is ‘about’ the projector gate, the plane where the film frame is caught by the projected light beam.” —William Raban, Perspectives on British Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1977

“The first great excitement is finding the idea, making its acquaintance, and courting it through the elaborate ritual of film production. The second excitement is the moment of projection when the film becomes real and can be shared with the audience. The former enjoyment is unique and privileged; the second is not, and so long as the film exists, it is infinitely repeatable.” —William Raban, Arts Council Film-Makers on Tour catalogue, 1980

HAND GRENADE

Gill Eatherley, 1971, colour, sound, 8 min (3 screens)

“Although the word ‘expanded’ cinema has also been used for the open/gallery size/multi screen presentation of film, this ‘expansion’ (could still but) has not yet proved satisfactory – for my own work anyway. Whether you are dealing with a single postcard size screen or six ten-foot screens, the problems are basically the same – to try to establish a more positively dialectical relationship with the audience. I am concerned (like many others) with this balance between the audience and the film – and the noetic problems involved.” —Gill Eatherley, 2nd International Avant-Garde Film Festival programme notes, 1973

“Malcolm Le Grice helped me with Hand Grenade. First of all I did these stills, the chairs traced with light. And then I wanted it to all move, to be in motion, so we started to use 16mm. We shot only a hundred feet on black and white. It took ages, actually, because it’s frame by frame. We shot it in pitch dark, and then we took it to the Co-op and spent ages printing it all out on the printer there. This is how I first got involved with the Co-op.” —Gill Eatherley, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

LIGHT MUSIC

Lis Rhodes, 1975-77, b/w, sound, 20 min (2 screens)

“Lis Rhodes has conducted a thorough investigation into the relationship between the shapes and rhythms of lines and their tonality when printed as sound. Her work Light Music is in a series of ‘moveable sections’. The film does not have a rigid pattern of sequences, and the final length is variable, within one-hour duration. The imagery is restricted to lines of horizontal bars across the screen: there is variety in the spacing (frequency), their thickness (amplitude), and their colour and density (tone). One section was filmed from a video monitor that produced line patterns on the screen that varied according to sound signals generated by an oscillator; so initially it is the sound which produces the image. Taking this filmed material to the printing stage, the same lines that produced the picture are printed onto the optical soundtrack edge of the film: the picture thus produces the sound. Other material was shot from a rostrum camera filming black and white grids, and here again at the printing stage, the picture is printed onto the film soundtrack. Sometimes the picture ‘zooms’ in on the grid, so that you actually ‘hear’ the zoom, or more precisely, you hear an aural equivalent to the screen image. This equivalence cannot be perfect, because the soundtrack reproduces the frame lines that you don’t see, and the film passes at even speed over the projector sound scanner, but intermittently through the picture gate. Lis Rhodes avoids rigid scoring procedures for scripting her films. This work may be experienced (and was perhaps conceived) as having a musical form, but the process of composition depends on various chance operations, and upon the intervention of the filmmaker upon the film and film machinery. This is consistent with the presentation where the film does not crystallize into one finished form. This is a strong work, possessing infinite variety within a tightly controlled framework.” —William Raban, Perspectives on British Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1977

“The film is not complete as a totality; it could well be different and still achieve its purpose of exploring the possibilities of optical sound. It is as much about sound as it is about image; their relationship is necessarily dependent as the optical sound track ‘makes’ the music. It is the machinery itself which imposes this relationship. The image throughout is composed of straight lines. It need not have been.” —Lis Rhodes, A Perspective on English Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1978

LINE DESCRIBING A CONE

Anthony McCall, 1973, b/w, silent, 30 min (1 screen, smoke)

“Once I started really working with film and feeling I was making films, making works of media, it seemed to me a completely natural thing to come back and back and back, to come more away from a pro-filmic event and into the process of filmmaking itself. And at the time it all boiled down to some very simple questions. In my case, and perhaps in others, the question being something like “What would a film be if it was only a film?” Carolee Schneemann and I sailed on the SS Canberra from Southampton to New York in January 1973, and when we embarked, all I had was that question. When I disembarked I already had the plan for Line Describing a Cone fully-fledged in my notebook. You could say it was a mid-Atlantic film! It’s been the story of my life ever since, of course, where I’m located, where my interests are, that business of “Am I English or am I American?” So that was when I conceived Line Describing a Cone and then I made it in the months that followed.” —Anthony McCall, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

“One important strategy of expanded cinema radically alters the spatial discreteness of the audience vis-à-vis the screen and the projector by manipulating the projection facilities in a manner which elevates their role to that of the performance itself, subordinating or eliminating the role of the artist as performer. The films of Anthony McCall are the best illustration of this tendency. In Line Describing a Cone, the conventional primacy of the screen is completely abandoned in favour of the primacy of the projection event. According to McCall, a screen is not even mandatory: The audience is expected to move up and down, in and out of the beam – this film cannot be fully experienced by a stationary spectator. This means that the film demands a multi-perspectival viewing situation, as opposed to the single-image/single-perspective format of conventional films or the multi-image/single-perspective format of much expanded cinema. The shift of image as a function of shift of perspective is the operative principle of the film. External content is eliminated, and the entire film consists of the controlled line of light emanating from the projector; the act of appreciating the film – i.e., ‘the process of its realisation’ – is the content.” —Deke Dusinberre, “On Expanding Cinema”, Studio International, November/December 1975

Back to top