Date: 2 November 2003 | Season: London Film Festival 2003 | Tags: London Film Festival

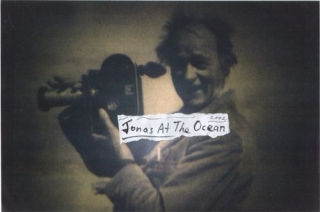

JONAS AT THE OCEAN

Sunday 2 November 2003, at 2pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

‘Jonas Mekas and his friends of free film, art and music.

A documentarypsychomusicfilm by Peter Sempel’

Peter Sempel, Jonas at the Ocean, Germany, 2002, 93 min

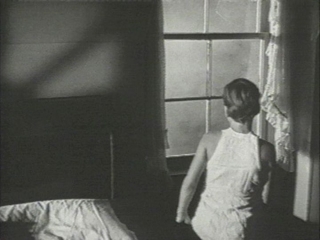

Together with his brother Adolphas, Jonas Mekas left Lithuania during World War II and eventually travelled to America as a ‘displaced person’. After settling in New York, he soon purchased a movie camera and began documenting the lives of Lithuanian immigrants. Within a few years, he was to become a central figure in the movement toward the recognition of film as art. The brothers’ arrival in New York (1949) is the film’s point of departure, and readings from ‘I Had Nowhere to Go’, Jonas’ autobiography of the period, appear throughout. Sempel loosely traces Mekas’ post-war life, as told through his interactions with other members of the arts community. There are visits with Robert Frank, Merce Cunningham and Nam June Paik, and with La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela in their ‘Dream House’. Allen Ginsberg tells the story of Pull My Daisy and the birth of beat cinema, while Phillip Glass speaks of Jonas’ independent sprit and the beginnings of the downtown arts scene in the 60s. Sempel borrows liberally from Mekas’ own films, while offering us glimpses of a life which we are more often used to seeing from his own point of view looking out.

PROGRAMME NOTES

JONAS AT THE OCEAN

Sunday 2 November 2003, at 2pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

JONAS AT THE OCEAN

Peter Sempel, Germany, 2002, 16mm, colour, sound, 93 min

It’s actually a prolongation of Jonas In The Desert, so Part Two, but with less talking and more music. I think , feel with music you can come nearer to something , someone than with any words (of course there are also interviews, for example with Jonas, Robert Frank, Nam June Paik, Phil Glass…) I’ve been filming Jonas (not shown at all in Part One) and also new scenes as I kept on filming after 1994, actually ’til, 2001. It starts with Jonas at the seashore in Lithuania laughing and filming children and running into the water with his Bolex camera, with ‘Starlight’ by Lou Reed and John Cale (about Warhol films), his hat flies away in the wind … He reads from his book, about the days in Germany … A wonderful scene where he repeats the landing at the Hudson with Algis and his brother Adolphas (filmed in slow motion – Jonas Scholz, the cameraman did a great job!) … Him running through the wide fields of his home country, chasing cows, hugging a white horse, and running to the horizon and back into the camera … Of course also in New York, and Torino, Barcelona, Paris, Berlin, Hamburg, Sao Paulo, Washington, Montauk and … and …

Some highlights: Robert Frank in his studio, talking about the old days, a ‘light show’ with La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela, Nick Cave reads from ‘I Had Nowhere To Go’ (the scene with the peepshow in the 1950s, 42nd Street, it’s beautiful and sad. Nick reads in his little green backyard house in London, dramatically (black + white, 16mm), it’s great.) … More guests: Rudy Burkhardt talking wildly about Maya Deren, Allen Ginsberg, Julius Ziz, Kenneth Anger, Tony Conrad (with a great performance in Buffalo), Stan Brakhage, Vincent Canby, Raimund Abraham, Peter Kubelka, Michael Snow, Fernando Arrabal, Zoe Lund and Harvey Keitel, Wim Wenders (calling Jonas the James Joyce of film art …), Blixa sings a song, Kiki and more … Jonas doing an Artaud performance on the Anthology-stage, at the top of his voice … Really quite crazy he is sometimes, how wonderful! Music: from underground, classical to Lithuanian folksongs. Okay, this could give you a little idea. The whole film is 93min on 16mm. —Peter Sempel

Back to top

Date: 2 November 2003 | Season: London Film Festival 2003 | Tags: London Film Festival

THE ILLUSION OF MOVEMENT

Sunday 2 November 2003, at 4pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

John Smith, Worst Case Scenario, UK, 2003, 18 min

This new work by John Smith looks down onto a busy Viennese intersection and a corner bakery. Constructed from hundreds of still images, it presents situations in a stilted motion, often with sinister undertones. Through this technique we’re made aware of our intrinsic capacity for creating continuity, and fragments of narrative, from potentially (no doubt actually) unconnected events.

Michele Smith, Like All Bad Men He Looks Attractive, USA, 2003, 23 min

Michele Smith, They Say, USA, 2003, 49 min

Michele Smith creates intense, hand-made collage films from a diverse assortment of film materials, mixing formats and contents with spontaneous regularity. Using a heavily re-edited 16 or 35mm film as a base, she manually weaves in other film footage, plastic shopping bags, translucent products, slides and other materials to create a master reel that is impossible to duplicate. Being too unwieldy to pass through a laboratory printer, the work must ultimately be shown on video, with the transfer done intuitively by hand, shooting frame-by-frame with a digital camera. Unlike, 2002’s Regarding Penelope’s Wake, these two new interchangeable pieces also contain digitally interwoven found video footage. They are truly amorphous time-based sculptures whose barrage of visual stimulus leave themselves wide open to personal interpretation. This is original and challenging work, demanding of its audience, and rewarding in its illumination.

‘I want my films to be open. The viewer creates the version of the film they will see by the way in which they view it. This is on a narrative, symbolic, metaphorical level as well as on a visual and structural level. The rapid intercutting and weaving of strands of different footage and elements creates a time space where one must mix what they are seeing for themselves. There is no way to perceive the links of still images into an illusion of movement. One can, with a readjusting of their viewing, change their experience of the work throughout.’ (Michele Smith)

PROGRAMME NOTES

THE ILLUSION OF MOVEMENT

Sunday 2 November 2003, at 4pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

WORST CASE SCENARIO

John Smith, UK, 2003, video, colour, sound, 18 min

For his latest work, Worst Case Scenario, Smith took four thousand still photographs of daily life on a Viennese street corner. The film re-orders and manipulates a selection of these images, and as it progresses the static world slowly and subtly comes to life. As Sigmund Freud casts his long shadow across the city, an increasingly improbable chain of events and relationships starts to emerge. —Open Eye Gallery

LIKE ALL BAD MEN HE LOOKS ATTRACTIVE

Michele Smith, USA, 2003, video, colour, silent, 23 min

THEY SAY

Michele Smith, USA, 2003, video, colour, silent, 49 min

This new work consists of one film split into two parts. Two parts which can be seen in either order, or separately if one so chooses.

In Like All Bad Men He Looks Attractive the mixed mediums are woven together on Mini DV. The materials are one reel of 35mm film and two reels of 16mm film. Inset into the 35mm film are plastic shopping bags, translucent plastic folders and plates, Mylar drafts used as blueprints for bridge construction, Viewmaster slides, paparazzi slides found at a tourist memorabilia shop on Hollywood Boulevard (including Zsa Zsa Gabor, Charlton Heston and George Peppard with a big white rabbit), slides purchased in the gift shops at the Getty Museum and at Hearst Castle, “sign here” tabs from my accountant, the wings of a dying butterfly that I tried to rescue from the hot pavement of a grocery store parking lot, Hollywood movie trailers, 8mm home movies and stag films, 16mm footage (including an episode of Green Acres), Viewmaster stills from 1970s TV shows, etc. Some things were not inset into the reel but recorded in the same manner and later cut in digitally. Panels, or film ‘carpets’: large mats made of 16mm film. Old magic lantern slides. The base film the elements are physically cut into is a workprint of raw footage of an unknown actor with a bandaged finger standing in front of the camera. He occasionally raises an envelope and reacts to a clapboard. I received this reel of film from a friend who’s a bit of a packrat (like myself). Before I met him, his house had burned down and this reel was one of the few items which survived. The decayed parts are where the emulsion melted from the heat.

The digital transfer was hand shot frame by frame against a crafter’s lightboard with a 25 watt candelabra bulb because the plastic folders and other elements inset into the 35mm would not go through the telecine transfer machine. I decided not to set an exact frameline and moved the filmstrip casually past the camera. This process added a feeling of the material celluloid form bending and moving as fast stills in time, with light reflecting through and glaring against it. I shot each frame as a still – which then had to be loaded into the Mac and sped up. It’s approximately equal to 10 frames per second, film speed. I alter this rhythm at different points in the film. There is also a cheesy faux-shutter effect for the still shots which was built into the camera I used – it becomes a chaotic and erratic half-flicker when sped up.

Intercut into this are found VHS tapes I bought with my grandmother at the local Greek deli and produce shop. They were getting rid of their rental videos and for some reason I must have looked like someone who would buy the entire shopping cart full because the shopkeeper made a deal and offered all of them to me. I used footage from four of these films in sections during both films. While watching these tapes I decided this material would be an interesting element to add to my film. Much of it is cut at an interval of three digital frames (which is about 30 frames per second) after every 12 frames of transferred film. A friend did this while I sat by and watched and told him where to split the images because I was at that point not too keen on editing digitally and did not know how it would turn out. Regarding Penelope’s Wake was pure in its filmic structure. The only digital editing done to that film was to clean up between reel changes and breaks in the film during transfer. By the end of the digital interweaving edits in the new films, I jumped in and did it myself and reworked some rhythm structures. As the work progressed, I became quite pleased with the possibilities and interactions of this new set of elements, and with the subtle contrasts and interactions of different mediums, times, and textures.

They Say consists of two reels of heavily edited (frame by frame) and overlaid 16mm film. It was then intercut with the grainy and scratchy melodrama rental tapes. I used a few 16mm found footage source reels as the main focus to play with narrative structure in a way related to but different than in my first work. I used a lot of footage from one narrative short film about a boy and a wild horse. When nearing the end I tired of editing it and decided to put it out into my garden and then dumped a few litter boxes on top. Contents: wood pellets and bunny poop. I forgot how long I left it outside … it rained a few times. Perhaps a week. It was later washed with laundry detergent and hot water.

I want my films to be open. The viewer creates the version of the film they will see by the way in which they view it. This is on a narrative , symbolic , metaphorical level as well as on a visual and structural level. The rapid intercutting and weaving of strands of different footage and elements creates a time space where one must mix what they are seeing for themselves. There is no one way to perceive the links of still images into an illusion of movement. One can, with a readjusting of their viewing, change their experience of the work throughout. —Michele Smith

Back to top

Date: 2 November 2003 | Season: London Film Festival 2003 | Tags: London Film Festival

FILM AS A SUBVERSIVE ART

Sunday 2 November 2003, at 7pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

Paul Cronin, Film as a Subversive Art: Amos Vogel and Cinema 16, UK, 2003, 56 min

Speaking recently about the myriad dangers facing humanity, director-provocateur Werner Herzog cited ‘the lack of adequate imagery’ as one of the most troubling. It’s a view Amos Vogel would surely endorse. As one of America’s most important curators, historians and festival directors, his influence on artists, experimental and underground film cannot be overstated. Born in Austria in 1922 but resident in New York since 1938, Vogel created the path-breaking film society Cinema 16 in 1947, introducing a continent to previously unseen worlds of experience. 20 years on, he established the New York Film Festival and with his eye-changing book ‘Film as a Subversive Art’, penned a revolutionary analysis of the moving image. Now, in Cronin’s valuable tribute to an extraordinary man and his times, Vogel delivers a series of compelling and entertaining reflections on a life lived in the passionate belief that film has a fundamental, radical and ethical role to play in society. Required viewing for anyone who believes cinema matters. Really matters. (Gareth Evans)

followed by

Exhibitionism: Subversive Cinema and Social Change

Following the screening of Film As A Subversive Art: Amos Vogel and Cinema 16 we will be staging a panel discussion focusing on some of the key issues raised in the film.

PROGRAMME NOTES

FILM AS A SUBVERSIVE ART

Sunday 2 November 2003, at 7pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

FILM AS A SUBVERSIVE ART: AMOS VOGEL AND CINEMA 16

Paul Cronin, UK, 2003, video, colour, sound, 56m

An hour-long profile of Amos Vogel, 82-year old New York resident and Austrian emigré, founder of the New York Film Festival and the Cinema 16 film society.

In 1947, Amos Vogel established a film club in New York called Cinema 16, the most important and influential film society in American history. At its height it boasted thousands of members, inspired a nationwide network of smaller film societies, and gave birth to the very rich tradition of post-war film culture that still exists in the United States. More than a decade before the father of modern ‘independent’ cinema – John Cassavetes – even picked up a camera, Vogel was bringing to a mass audience new ways of looking at world cinema.

The audiences of Cinema 16 were presented with a wide range of film forms, often programmed so as to confront – and sometimes to shock – conventional expectations, including works of the avant-garde, documentaries of all kinds, experimental animation, and foreign or independent features and shorts not in distribution in the United States. From the very beginning Vogel was determined to demonstrate that there was an alternative to industry-made cinema. Initially concentrating on non-fiction, he became the first programmer to show the works of Polanski, Cassavetes, De Palma, Kluge, Oshima, Ozu, Polanski, Rivette and Resnais (among many others) to American audiences. Vogel saw himself as a special breed of educator, using an exploration of cinema history and current practice not only to develop a more complete sense of the myriad experiences film culture had to offer, but also to invigorate the potential of citizenship in a democracy, and cultivate a sense of global responsibility.

Film as a Subversive Art: Amos Vogel and Cinema 16 tells the story of Cinema 16 through a vivid compilation of images and sounds, including a selection of newly filmed interviews with Amos Vogel (erudite and charismatic on-camera) and historian Scott MacDonald, author of a recent book about Vogel and Cinema 16. Vogel is filmed in various New York locations that are pertinent to the history of Cinema 16 and to New York film culture in general. There are rostrum shots of some of the photographs and beautifully designed catalogues and leaflets from Vogel’s extensive Cinema 16 archive. The film also contains excerpts from a selection of films screened at Cinema 16 between 1947 and 1963, including Roman Polanski’s Two Men and a Wardrobe, the infamous Nazi propaganda film The Eternal Jew, and the only film made by legendary New York press photographer Weegee. —Paul Cronin

Back to top

Date: 2 November 2003 | Season: London Film Festival 2003 | Tags: London Film Festival

UNKNOWN PARTS OF THE WORLD

Sunday 2 November 2003, at 9pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

Thomas Comerford, Figures in the Landscape, USA, 2002, 11 min

Grainy, undefined images shot with a pinhole camera accompany recitations of texts tracing the history of suburban housing from the rudimentary dwellings of Native Americans and the early settlers. An inquiry into human interaction with the landscape and notions of land development.

David Gatten, Secret History of the Dividing Line, USA, 2002, 20 min

Text-based, hand-processed treatment of Colonel William Byrd II’s 1728 expedition to settle disputes on the boundary between two American states, as chronicled in his ‘Histories of the Dividing Line Betwixt Virginia and North Carolina’.

Ben Russell, Terra Incognita, USA, 2002, 10 min

‘A lenseless film, whose cloudy images produce a memory of history. Ancient and modern explorer’s texts on Easter Island are garbled together by a computer narrator, resulting in a forever repeating narrative of discovery, colonialism, loss and departure.’

Phil Solomon, Psalm III: Night of the Meek, USA, 2002, 23 min

Obscure, ghostly faces emerge from a degraded, murky image, not through animation, but chemical and optical treatments of re-photographed and original material. A transcendental nightmare vision based on the legend of the golem. ‘A Kindertotenlieder in black and silver, on a night of gods and monsters.’

Naoyuki Tsuji, A Feather Stare at the Dark, Japan, 2003, 17 min

Pencil animation telling the mystical pre-history of the world through surreal, transformational drawings which depict the struggle between good and evil at the origins of evolution.

PROGRAMME NOTES

UNKNOWN PARTS OF THE WORLD

Sunday 2 November 2003, at 9pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

FIGURES IN THE LANDSCAPE

Thomas Comerford, USA, 2002, 16mm, colour, sound, 11 min

In making films with a pinhole camera, returning to a technology that predates the invention of cinema, Thomas Comerford uses consciously archaic means to comment on cinema’s technology and on technological progress in general. The fragile, fuzzy images that result from the replacement of the camera lens by a tiny hole have a wispy, almost virtual quality that refers back to the camera obscura of the Renaissance. Figures in the Landscape, set in Schaumburg, one of the Chicago area’s more sprawling suburbs, includes town maps and plans as well as images of people standing amid empty, almost soul-less spaces. Comerford uses found texts to describe the nature of suburban development and the way high-tech homes have replaced the more ‘primitive’ dwellings of Indians and early European pioneers, thus comparing his pinhole technique with early residents’ primitive homes on the one hand while the slicker and higher-tech cinema which he eschews is implicitly paralleled to the new homes of Schaumburg on the other. Comerford’s ironic point about ‘progress’ is reinforced when we hear about the Indians’ use of trees as trail markers while seeing a giant pole, and hear about early pioneer homes while seeing a particularly vulgar oversized modern dwelling. —Fred Camper

SECRET HISTORY OF THE DIVIDING LINE

David Gatten, USA, 2002, 16mm, b/w, silent, 20 min

When using tape to make a splice the cut pieces of film are placed end to end and the tape itself covers the gap: it is a band-aid and a bridge. But as the splice ages a line becomes visible; eventually the adhesive dries and the connection dissolves. When making a cement splice, there is more violence involved. The films are not placed end to end but instead are crushed into one another. Frames are lost, emulsions are scraped. But the well made splice is strong: in fact, it is permanent. Unlike tape, there is no going back. And it leaves a mark – a line – covering a third of one of the frames. A splice marks difference and defines duration. To suppress that mark is to pretend that we will live forever. Instead, take your splicer and knock the blade out of alignment. Forego the B-roll in favour of a single strand of faith. Hold your breath and count the hours since you were last together. Blow softly on a wet face and watch the smile form. Float your hand across the surface and find all the words you need. Unfold the splicer and separate your image from your dream; you will feel bound, as if tied down until you are fully awake. Only then will you know for sure: this may not be final but it is definite. The landscape you see can change only when you pass through it. Regard your new object: a union: silent, tiny and bright. Paired texts as duelling histories; a journey imagined and remembered; 57 mileage markers produce an equal number of prospects. The latest in a series of films about the division of landscapes, objects, people, ideas and the Byrd family of Virginia during the early 18th century. —David Gatten

TERRA INCOGNITA

Ben Russell, USA, 2002, 16mm, colour, sound, 10 min

In the in-between of history and memory lies the Unknown Part of the World. I have seen it, however briefly – projected out in front of my eyes like some old-timey silent film. I knew the place immediately, what with its rusted factories , fallen statues , floating figurines, but the image was lost as soon as the reel ran out. Played it back. Mapped out the sounds. Grabbed a camera, a makeshift recording device, played it back. And again. Each time I cobbled together a newer world, cut and spliced out of words and images from this one; but they seem to accumulate, these geographies – each one charted proposes an entirely different set of islands , continents , planets moving about just beyond the horizon. Therein lies the joy and terror; and throughout all of it, this camera here is but a minor tool in sifting through this shifting terrain. —Ben Russell

PSALM III: NIGHT OF THE MEEK

Phil Solomon, USA, 2002, 16mm, b/w, sound, 23 min

It is Berlin, November 9, 1938, and, as the night air is shattered throughout the city, the Rabbi of Prague is summoned from a dark slumber, called upon once again to invoke the magic letters from the Great Biij that will bring his creatures made from earth back to life, in the hour of need. A Kindertotenlieder in black and silver, on a night of gods and monsters …

In Germany, Before the War:

I’m looking at the river,

but I’m thinking of the sea,

thinking of the sea,

thinking of the sea …

I’m looking at the river,

but I’m thinking of the sea,

thinking of the sea,

thinking of the sea … —Phil Solomon

A FEATHER STARE AT THE DARK

Naoyuki Tsuji, Japan, 2003, 16mm, b/w, sound, 17 min

This is the tale in the pre-world before bearing our earth. There is the world in chaos with the existence of the force of the good and evil that has interfered with each other. And it is going to build the chance of birth in the New World. The pre-world is carrying out a growth expansion at the same time, going to decay. However, the force of the decay sets up birth in the coming world. —Naoyuki Tsuji

Back to top

Date: 30 October 2004 | Season: London Film Festival 2004 | Tags: London Film Festival

THE TIMES BFI 48th LONDON FILM FESTIVAL

Saturday 30 – Sunday 31 October 2004

London National Film Theatre

As with last year, the Experimenta Avant-Garde Weekend will present a concentrated, international programme of artists’ film and video. It is a unique opportunity to survey some of the most original and vital works made around the world in recent years, and our only annual chance to do so on such a scale in England.

This year’s festival includes new films by old masters such as Bruce Conner, Peter Kubelka and Jonas Mekas, alongside work by younger artists including Michaela Grill, Julie Murray and Emily Richardson. There is an opportunity to discover the work of forgotten pioneer José Val del Omar, and featured artist Nathaniel Dorsky will present a lecture to introduce his exquisite silent films. All the mixed programmes plus selected features will be shown over the two-day period, and several of the filmmakers will be present to discuss their work.

Outside of the weekend, the festival also features screenings of Jennifer Reeves’ feature The Time We Killed, Gianikian & Ricci Lucchi’s Oh, Uomo, both versions of Straub / Huillet’s Une Visite au Louvre and a newly preserved print of Shirley Clarke’s Portrait of Jason.

Date: 30 October 2004 | Season: London Film Festival 2004 | Tags: London Film Festival

VIDEO VISIONS

Saturday 30 October 2004, at 2pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

fordbrothers, Preserving Cultural Traditions in a Period of Instability, Austria, 2004, 3 min

fordbrothers explode the visual field as a strangely familiar, but unidentified, voice rails against computer technology and modern society.

Fred Worden, Amongst the Persuaded, USA, 2004, 23 min

The digital revolution is coming, and an old-school film-maker is trying to come to terms with it. ‘The human susceptibility to self-delusion has, at least, this defining characteristic: Easy to spot in others, hard to see in oneself.’ (Fred Worden)

Didi Bruckmayr & Michael Strohmann, Ich Bin Traurig, Austria, 2004, 5 min

An aria for 3D modelling, transformed and decomposed using the cultural filters of opera and heavy metal.

Robin Dupuis, Anoxi, Canada, 2003, 4 min

Effervescent digital animation of vapours and particles.

Michaela Grill, Kilvo, Austria, 2004, 6 min

Minimal is maximal. A synaesthestic composition in black, white and grey.

Myriam Bessette, Nuée, Canada, 2003, 3 min

Bleached out bliss of dripping colour fields.

Jan van Nuenen, Set-4, Netherlands, 2003, 4 min

Endless late night cable television sports programmes, remixed into deep space: from inanity to infinity.

Robert Cauble, Alice in Wonderland Or Who Is Guy Debord?, USA, 2003, 23 min

Alice longs for a more exciting life away from Victorian England, but is she ready for the Society of the Spectacle? Conventional animation is subverted to tell the strange tale of Alice and the Situationists.

PROGRAMME NOTES

VIDEO VISIONS

Saturday 30 October 2004, at 2pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

PRESERVING CULTURAL TRADITIONS IN A PERIOD OF INSTABILITY

fordbrothers, Austria, 2004, video, colour, sound, 3 min

Preserving Cultural Traditions in a Period of Instability is a computer-generated video based on artefacts occurring during compression procedures. A short hypnotic and monotonous sound-loop underlines the structural character of the video footage, whilst a commentary by Stan Brakhage on the rise of digital technologies and new media forms the second sound layer. (Thomas Draschan)

AMONGST THE PERSUADED

Fred Worden, USA, 2004, video, colour, sound, 23 min

The human susceptibility to self-delusion has, at least, this defining characteristic: Easy to spot in others, hard to see in oneself. This film began as an effort to channel the stresses engendered by my daily New York Times fix. The news of the world read as a relentless collective descent into a 21st century Jonestown. More accurately, into a scattered offering of competing Jonestowns, each proffering its own distinctive brand of cool aid. In the free marketplace of mindsets, you’re free to choose your poison. Each of us sees things in our own way. What I was seeing was that the common denominator driver of so many of the man-made disasters charted in each day’s New York Times was the human penchant for delusional thinking. The war on terror, to cite only one simple example, seemed to me essentially reducible to their delusions versus our delusions, with the stakes being who will be the first to have its ass handed to it. My decision to make the mechanics and infrastructure of self-delusion the subject of a film was easy enough once I committed to two operating principles. The first was that the film had to be about my delusions and those of my milieu rather than about their delusions. The second, somewhat contradictory principle is that it really is impossible to see one’s own delusions. The essence of self-delusion as pathology is that it is at all times invisible to its host. For this reason, I could not cast this film with my actual delusions, but rather had to work with analogue surrogates. This suited my purposes just fine as my interest was never with the actual content of delusional thinking, but rather with its forms. How we get there, move in, make ourselves comfortable and then bend our talents to defending the fort. How the most gracious and nimble of mental eruptions can end up tripping down the slippery slope from inspired possibility through true belief to leaden and entrenched delusion. With a cast of available characters acting as themselves. Don’t believe a word. See the iron jaws of the mechanism at work as the filmmaker falls into the biggest and most obvious delusion of all: the belief that he can master his own delusions by making a film about them. (Fred Worden)

ICH BIN TRAURIG (I AM SAD)

Didi Bruckmayr & Michael Strohmann, Austria, 2004, video, colour, sound, 5 min

Ich Bin Traurig (I am sad) is part of a series of works on “digital translations of reality” (Didi Bruckmayr). Fuckhead – one of the band projects of cultural workers Bruckmayr/Strohmann – is one of these translation projects. The masculinity-charged raging of brachial heavy metal music runs – analogue to the technical processes of sound mixing – through the filter of another cultural form of expression: the opera and its melodramatic employment of voices, as well as the distant, cool, electronic creation of sound. The result is a bastard, a science-fiction being whose existence grows increasingly precarious. Fuckhead possibly tells – in image and sound and data – of human sensibilities at the edge, of that which the author J.G. Ballard calls “psychopathologies of the future” (in his epochal novel Crash). The expression quite aptly represents this video. Its “clinical picture” is that of the love sick, intense sorrow at the loss of love: “I am sad, because you do not understand me / melancholy steals my sleep at night.” Siemar Aigner’s pathetic bass drowns out the scratchy surface of electronic accompaniment. The antagonism between the Spartan electronics, which tend to refuse to lead the melody, and the presence of a human voice is mirrored in the visual translation of the number: the image of a human face (created in a computer by means of 3-D software) is horizontally deformed to the rhythm of the verse, disheveled along the lines of the acoustic information from the computer. When the song stops, black takes over the picture and narrows the narrative space down to music. The absence of the human element is heavier (textually, as well as visually) than its presence. (Michael Loebenstein)

ANOXI

Robin Dupuis, Canada, 2003, video, colour, sound, 4 min

The images are generated frame by frame as stills, usually generated from simple shape or forms (square, circle, line etc.), and processed in various commercial software (Photoshop, Vegas, DL Combustion) and/or open source software (Drone, Bidule), before and/or after being edited in sequence. I produce a lot of images and animated sequences to create what I call an image bank, from which I select parts for each project I work on. I do the same for sound. The image and sound in Anoxi is pure synthesis, there is no capture, scan or recording of external material of any sort. (Robin Dupuis)

KILVO

Michaela Grill, Austria, 2004, video, b/w, sound, 6 min

A remote, barren, almost unfriendly landscape: Kilvo in Lapland was the inspiration for Radian’s music, and even the accompanying visuals by Michaela Grill play with the bare countryside’s resistance to its depiction. A fourfold split screen shows views of this place in a kaleidoscope of animated digital postcards. The normal associations – visions of majestic, or at least marketable, beauty, of exotic or untouched wilderness – are consistently undermined in Kilvo. Instead of showing an idyll, the landscape is reduced to the greatest degree possible. Lines and contours are stripped from the background of black, white and grey tones. The viewer cannot be sure what is being shown, or implied. For brief moments fleeting images appear then change or are lost. Faithful reproductions are not the important thing here, but the digital transformation of a real landscape into an abstract pattern, translation into a completely different visual form, which at the same time conforms to this landscape. For all its reduction and structural austerity Kilvo also has a playful aspect. The movement in the screen sections is tied to the articulated rhythm of the music and its modulation. The sounds and images are combined in an entertaining and complex game with structures, and with musical and visual synchronisms. In the end everyone can invent Kilvo for themselves. In their reservation and simultaneous openness, the sounds and images offer a projection screen for the viewers’ mental images, for the search for their own imaginary landscape. (Barbara Pichler)

NUÉE

Myriam Bessette, Canada, 2003, video, colour, sound, 3 min

Though synthetically constructed, the fleeting works of Myriam Bessette bring rare tactile qualities to the digital medium. Her earlier videos Nutation and Azur bestowed an organic delicacy to the pure cathode ray signal. In Nuée, streaks of muted hues merge to form a constantly shifting colour field that is overlaid with abstract verdant flecks. The sensorial experience is heightened by a fizzing electronic soundtrack. (Mark Webber)

SET-4

Jan van Nuenen, Netherlands, 2003, video, colour, sound, 4 min

On the TV station Eurosport, the hours between the really exciting matches are filled up with sports pulp. You see endless games, sets and matches ‘live’, accompanied by lethargic commentary. Out of exasperation, Jan van Nuenen recorded three examples of this, which he mixed, overlapped and superimposed into loops. What starts as an ordinary game of ping-pong develops into a kaleidoscopic spiral of dancing high servers, flying springboard divers and rhythmically chopping table-tennis bats. Eventually it becomes a scene that appears to represent the culmination of a bizarre acid dance party. (Jaap Vinken & Martine van Kampen)

ALICE IN WONDERLAND OR WHO IS GUY DEBORD?

Robert Cauble, USA, 2003, video, colour, sound, 23 min

Alice in Wonderland, or Who Is Guy Debord? pairs footage from the Disney cartoon with an alternate sound track. Alice’s quest for the help of philosopher Guy Debord (The Society of the Spectacle) is punctuated by an assaultive TV montage that includes Bush’s aircraft carrier landing. (Chicago Reader)

Back to top

Date: 30 October 2004 | Season: London Film Festival 2004 | Tags: London Film Festival

TRAVEL SONGS

Saturday 30 October 2004, at 4pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

Robert Breer, What Goes Up, USA, 2003, 5 min

A volley of rapid visual associations from the mind of Robert Breer, animating collage, drawings and snapshots in a playful, but rigorous manner. What goes up must come down.

Jonas Mekas, Travel Songs 1967-1981, USA, 2003, 24 min

In short bursts and single frames, memories of European journeys rush by like landscapes through train windows. This ebullient album of previously unseen footage contains songs of Assisi, Avila, Moscow, Stockholm and Italy.

Frank Biesendorfer, Little B & MBT, USA-Germany, 2003, 30 min

An intimate journal featuring the film-maker’s family in their daily life, contrasted with audio recorded at one of Hermann Nitsch’s actions in his Austrian castle. Despite their diverse sources, the sound and image weave a tangled spell around each other.

Robert Fenz, Meditations on Revolution V: Foreign City, USA, 2003, 32 min

The Meditations series comes home for a journey through New York, viewed as a place of immigration and displacement. The urban environment, shot mostly at night in ecstatic black-and-white, becomes an almost exotic locale. Fenz’s incandescent cinematography reveals images of great beauty and compassion on the sidewalks and subway, as the film subtly shifts from anonymous street scenes into a sensitive portrait of jazz legend Marion Brown, who reminisces on his life and career as he convalesces in hospital.

PROGRAMME NOTES

TRAVEL SONGS

Saturday 30 October 2004, at 4pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

WHAT GOES UP

Robert Breer, USA, 2003, 16mm, colour, sound, 5 min

In observance of gravity – the airplane, the priapic flesh, the deciduous leaf, the upturned nose, the kitten up a tree, the towering Empire – All Must Fall. As a man who fell to earth Breer branches off into playful tangents and bursts creating complex spaces cartwheeling through time’s latest seasons. Quick as a snapshot, hard as a slingshot, lighter than a ton of feathers. (Mark McElhatten, New York Film Festival Views from the Avant-Garde)

TRAVEL SONGS 1967-1981

Jonas Mekas, USA, 2003, 16mm, colour, sound, 24 min

Mekas’ sublime Travel Songs, each of which run for five minutes or less, communicate the colourful and deepened sense of their varied locales (Italy, Russia, New York, etc). Mekas’ camera is always in motion, restlessly flipping back and forth on seemingly impossible zigzag trajectories. Central to his work is a feeling of forward momentum, Mekas sees the human condition as a hurtling train of experience. The momentary, split-second pauses in his camera movements – often focusing on either the fruits of nature or specific aspects of human physiognomy – suggest myriad paths of understanding and enlightenment. Mekas desperately tries to drink it all in and, happily for him and for us, fails. Like an immortal flower in constant bloom, Mekas’ films are an ever-expanding document of life in perpetual motion, personal profundity at twenty-four frames per second. (Keith Uhlich)

LITTLE B & MBT

Frank Biesendorfer, USA-Germany, 2003, 16mm, colour, sound, 30 min

The soundtrack is made from my recordings of voices, discussions and sounds surrounding a recent Hermann Nitsch action in Austria. The images, consisting primarily of special and intimate moments of his wife and children, intertwine with the audio in strange and ambiguous ways. The film battles itself in order to cancel itself out, but the conflict remains circular and supersedes both the audio and visual, in a place beyond the material and physical. (Frank Biesendorfer)

MEDITATIONS ON REVOLUTION V: FOREIGN CITY

Robert Fenz, USA, 2003, 16mm, colour, sound, 32 min

The final film in Fenz’s series “Meditations on Revolution.” The film is dedicated to the director’s father who immigrated to the United States in 1953 and passed away in 1999. Foreign City studies New York as a place of immigration and displacement. It is a meditation on revolution of the urban space. Its abstract black and white images and actual sounds come in and out of synch, creating a magical foreign landscape. The reconstruction of N.Y. through an imaginary city plan, built on sensation. The film has a timeless, anonymous quality until it is given the voice of artist and jazz musician Marion Brown. (Robert Fenz)

Back to top

Date: 30 October 2004 | Season: London Film Festival 2004 | Tags: London Film Festival

PUBLIC LIGHTING

Saturday 30 October 2004, at 7pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

Mike Hoolboom, Public Lighting, Canada, 2004, 76 min

Public Lighting is a meditation on photography and the creation of images that can capture, replace and outlive our experiences. It’s a videofilm in seven parts, related in both subject and sentiment to the wonderful Imitations of Life, which screened in last year’s festival. Each chapter is a case study of the different types of personality that have been identified by the young author who guides us through the prologue. The first, a gay male, takes us on a tour of the bars and restaurants where his affairs have ended, recounting ironic stories of his many lovers. An homage to composer Philip Glass is incongruously followed by ‘Hey Madonna’, a confessional letter to the singer from a fan who is HIV positive. Amy celebrates another birthday, but concedes that she has lost her memory to television. At least she has a camera: ‘I take pictures not to help me remember, but to record my forgetting.’ Hiro lives life at a distance, rarely venturing out beyond the lens, and an anxious young model recounts poignant events from her past. Few film-makers use re-appropriated footage in such an emotive way: At once humorous and incisive, these chains of images inevitably lead us back to parts of ourselves. Hoolboom’s recent work is in such profound sympathy with the human condition that it speaks directly to our hearts.

PROGRAMME NOTES

PUBLIC LIGHTING

Saturday 30 October 2004, at 7pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

PUBLIC LIGHTING

Mike Hoolboom, Canada, 2004, FORMAT, COLOUR, SOUND, 76 min

“How do we tell the story of a life? What cruel reduction of an image will stand (in the obituary, the family photo album, the memory of friends) for the years between a grave and a difficult birth? Public Lighting examines the current media obsession with biography, offering up “the six different kinds of personality” (the obsessive, the narcissist) as case studies, miniatures, possible examples.” (Mike Hoolboom)

“Mike Hoolboom puts together some disparate clips, some beautiful images and hesitant shots from family, fiction, reality archive and advertising films (the Japanese advertisement for an all-purpose cleaning fabric is hilarious). Some images have been found or borrowed while others are original and have been shot for the purposes of the film. In the images there are also words, uttered in short sentences, and the voices of men and women. But this is only half the story. The filmmaker uses a dual approach to images and sounds to construct his unique universe. On the one hand, he gives them depth by slowdown effects, fade-ins and fade-outs, solarization, intermingling of visuals and sound in a complex dramatisation relationship. Public Lighting thus consists of strong images that show us the ages of history, its moments of grandeur and shame, touching on the public and private spheres, mingling show-biz and intimacy. An image in a Hoolboom film is always multiple, a confusing palimpsest that is embedded at a certain point in a different image, a pagan icon that keeps trace of the movement of a body, the expression of a face, the inflection of a voice. On the other hand, although this magnificently impure film is based on a very elaborate editing rhetoric, its profound movement leads to uninterrupted mediation.

“Public Lighting consists of six portraits which a young writes announces at the beginning of the film. These six people tell of ordinary follies, narcissistic obsessions, demiurgic desires and wounded memories. The separated man, the obstinate pianist, the ageing singer, the Chinese émigré, the nocturnal Japanese and the confessed woman are fragments of a collective history. The warm lighting used by Mike Hoolboom illuminates sleepless nights when one is no longer prepared to be deceived – at least for a while – by the ghostly apparitions that haunt our dreams. A single image then appears to emerge. That of a poetic intelligence worried about the world, in which the grave and lucid Hoolboomian hero aspires to some recognition, to a semblance of eternity and to a ‘genuine’ place in the movement of life.”

(Jean Perret, Visions du Reel Catalogue)

Back to top

Date: 30 October 2004 | Season: London Film Festival 2004 | Tags: London Film Festival

POETRY AND TRUTH

Saturday 30 October 2004, at 9pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

Larry Jordan, Enid’s Idyll, USA, 2004, 17 min

An animated imagining of Arthurian romance based on Gustav Doré’s engraved illustrations for Tennyson’s ‘Idylls of the Kings’, accompanied by the music of Mahler’s ‘Resurrection Symphony’.

Julie Murray, I Began To Wish, USA, 2003, 5 min

Mysterious events unfold in a potting shed … A jewel of found footage, mysterious and profound beyond its imagery, and with an almost deafening aural presence, despite its lack of soundtrack.

Rebecca Meyers, Things We Want To See, USA, 2004, 7 min

An introspective work that obliquely measures the fragility of life against boundless forces of nature, such as Alaskan ice floes, the Aurora Borealis and magnetic storms.

Peter Kubelka, Dichtung Und Wahrheit, Austria, 2003, 13 min

In cinema, as in anthropological study, the ready-made can reveal some of the fundamental ‘poetry and truth’ of our lives. Kubelka has unearthed sequences of discarded takes from advertising and presents them, almost untouched, as documents that unwittingly offer valuable and humorous insights into the human condition.

Morgan Fisher, ( ), USA, 2003, 21 min

‘I wanted to make a film out of nothing but inserts, or shots that were close enough to being inserts, as a way of making them visible, to release them from their self-effacing performance of drudge-work, to free them from their servitude to story.’ (Morgan Fisher)

Ichiro Sueoka, T:O:U:C:H:O:F:E:V:I:L, Japan, 2003, 5 min

Like Fisher’s film, Sueoka’s video also uses cutaways, but this time the shots are from 60s spy dramas, and retain their soundtracks. Stroboscopically cut together, it becomes a strange brew, like mixing The Man from U.N.C.L.E with Paul Sharits’ T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G.

Bruce Conner, Luke, USA, 2004, 22 min

In 1967 Bruce Conner visited Dennis Hopper, Paul Newman and others on the set of Cool Hand Luke and shot a rarely seen roll of silent 8mm film of the production. Almost forty years later, he has returned to this footage and presents it at three frames per second, creating an almost elegiac record of that time. Patrick Gleeson, Conner’s collaborator on several previous films, has prepared an original soundtrack for this new work.

PROGRAMME NOTES

POETRY AND TRUTH

Saturday 30 October 2004, at 9pm

London BFI Southbank NFT3

ENID’S IDYLL

Larry Jordan, USA, 2004, 16mm, b/w, sound, 17 min

I have used 46 engraved Doré illustrations to “Idylls of the King” as settings for his extravagantly romantic saga. As Enid, the protagonist, is seen in a vast array of scenes from deep forests to castle keeps, her champion is sometimes with her, sometimes away fighting archetypal foes. She dies and, through the magic of Gustav Mahler’s resurrection symphony, lives again. (Larry Jordan)

I BEGAN TO WISH

Julie Murray, USA, 2003, 16mm, colour, silent, 5 min

The sea sucks the seed back into the ocean, the flowers fold like umbrellas, shoots recoil into hiding, in seeds that shrink. The plants accelerate their tremble and wobble and glass unbreaks all around them. Strawberries blanch and tomatoes grow pale. The father, leering, holds forth a flower and suddenly his smile fades to awful seriousness. In an odd concentrated ritual the father and son carefully tip over all the flower pots, laying the plants to rest and it is in this end, around the time he figures the flowers are talking to him, that the son wishes his father had killed him. (Julie Murray)

THINGS WE WANT TO SEE

Rebecca Meyers, USA, 2004, 16mm, colour, sound, 7 min

A visit to a place they had seen many times, but wouldn’t again. Just before we left, the northern lights, which she tells me she had always wanted to see (waking in the early hours and waiting), hinted in the sky. Months after she was gone, I heard this recording for the first time. (Rebecca Meyers)

DICHTUNG UND WAHRHEIT

Peter Kubelka, Austria, 2003, 35mm, colour, silent, 13 min

Poetry and Truth was originally presented, albeit in a different format, during one of the “What Is Film” lectures at the Austrian Film Museum in Vienna, in this case on the subject of ‘acting and being’. In addition to screening a behind the scenes reel filmed on the set of The Misfits, Kubelka showed 13-minutes of footage shot by unidentified cameramen for a number of TV commercials made by an Austrian production company. Given that his one-minute masterpiece, Schwechater (1958), began life as a commission for a beer commercial, it would appear that his imagination had once again been aroused by the phantom world of advertising. While assembling the footage for demonstration purposes, the filmmaker succumbed to the impulse to also make the images speak with their own strange and beautiful logic. It would be misleading to call Poetry and Truth a ‘found’ film. Its footage has been gathered, selected, and edited together at very specific junctures to produce an archival, pedagogical, and yet weirdly electrifying collection of ethnographic camera ‘views’. But instead of recording an unknown tribe’s way of life in the wilderness, this ethnography bears witness to certain of our own Western rituals – namely “make believe,” “you should own,” and “go and buy.” Following his ‘metric’ and ‘metaphoric’ film phases, the latter exemplified by Unsere Afrikareise (1966), Kubelka now submits a new type of cinema for our consideration: the ‘metaphysical’ film. Metaphysical in the sense that, for the first time in his career, Kubelka allows the medium’s materiality (i.e., what film physically consists of) to recede, and instead foregrounds cinema’s magical capacity to locate and record anthropological rules, rituals, and myths in the unlikeliest of places. Poetry and Truth features twelve such ‘stories’; twelve sequences, each composed of one shot that is repeated in three, or five, or a dozen variations. Each take captures a movement from a stasis to motion and back again. For Kubelka, the repetition of physical movement – as in dance, as in film, as in life – is the fundamental law of the universe, from which even civilisation’s most complex systems derive. The act of conveying this principle via the ‘truth’ (the camera originals) of commercials is certainly a form of ‘poetry’ – but that’s not the source of the film’s title. At some point in each of these takes, the divine light of illusion falls upon people, dogs, buckets, and pasta. These simple truths’ are abruptly transformed into actors of ‘poetry’, and then, just as suddenly, fall back into their original non-poetic selves. As archaeologist and archivist, Kubelka is dutifully passing these telling artefacts on to the researchers of future generations. It’s easy to see why Kubelka doesn’t want Poetry and Truth to be thought of as a critique of advertising. He’s after something more essential and isn’t interested in using his work to express trivial opinions about some aspect of modern life. He’d rather champion the joy of rhythm, the joy of life, and affirm the cyclical nature of human endeavour – even if it means affirming and preserving the remnants of a trivial economy in the process. (Alexander Horwath, Film Comment)

( )

Morgan Fisher, USA, 2003, 16mm, colour, silent, 21 min

The origin of ( ) was my fascination with inserts. Inserts are a crucial kind of shot in the syntax of narrative films. Inserts show newspaper headlines, letters, and similar sorts of significant details that have to be included for the sake of clarity in telling the story. I have long been struck by a quality of inserts that can be called the alien, and as well the alienated. Narrative films depend on inserts (it’s a very rare film that has none), but at the same time they are utterly marginal. Inserts are far from the traffic in faces and bodies that are the heart of narrative films. Inserts have the power of the indispensable, but in the register of bathos. Inserts are above all instrumental. They have a job to do, and they do it; and they do little, if anything, else. Sometimes inserts are remarkably beautiful, but this beauty is usually hard to see because the only thing that registers is the news, the expository information, that the insert conveys. That’s the unhappy ideal of the insert: you see only what it does, and not what it is. This of course is no more than the ideal of all the instruments of narrative filmmaking and the rules that govern their use. A rule, or a method, underlies ( ), and I have obeyed it, even if the rule and my obedience to it are not visible. I needed the rule to make the film; it is not necessary for you to know what it is. A rule has the power of prediction, but only if you see it. To the extent that the rule remains invisible, the unfolding of the film is, for better or worse, difficult to foresee. The important thing is what the rule does. No two shots from the same film appear in succession. Every cut is a cut to another film. There is interweaving, but it is not the interweaving of dramatic construction, where intention and counter-intention are composed in relation to each other to produce friction that culminates in a climax. Instead it is an interweaving according to a rule that assigns the shots as I found them to their places in an order. In keeping with my wish to locate ( ) as far as possible from the usual conventions of cutting, whether those of montage or those of story films, the rule that puts the shots in the order has nothing to do with what is happening in them. I wanted to free the inserts from their stories, I wanted them to have as much autonomy as they could. I thought that discontinuity, cutting from one film to another, was the best way to do this. It is narrative that creates the need for an insert, assigns an insert to its place and keeps it there. The less the sense of narrative, the greater the freedom each insert would have. But of course any succession of shots, no matter how disparate, brings into play the principles of montage. That cannot be helped. Where there is juxtaposition we assume specific intention and so look for meaning. Even if there is no specific intention, and here there is none, we still look for meaning, some way of understanding the juxtapositions. At each cut I intended only discontinuity, cutting from one film to another, but beyond that nothing more. Indeed, beyond that simple device I could not intend any specific meaning, because whatever happens at each cut is the consequence of whatever two shots the rule put together, and the rule does not know what is in the shots. So what happens specifically at each cut is a matter of chance. (Morgan Fisher)

T:O:U:C:H:O:F:E:V:I:L

Ichiro Sueoka, Japan, 2003, video, colour, sound, 5 min

This is part of the “Requiem for Avant-Garde Film” series. (An example of minimal film for re-reading of Structural Films.) The concept of this work was combined with Paul Sharits’ film, T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G (1968) and the cliché of the Hollywood cinema, especially, crime suspense thrillers. And the title was extracted from Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1957). We could often see the depiction of a close-up hand in cinema, and we may find out that hand was a criminal’s hand. And a flicker was used to signify a crime. That is to say, in a cinema, a hand and flicker are the codes that make the representation of ‘evil’. (Ichiro Sueoka)

LUKE

Bruce Conner, USA, 2004, video, colour, sound, 22 min

Luke is a poetic film document created entirely by Bruce Conner in 1967 during one day of the production of Cool Hand Luke on location near Stockton, California on a country road. The main subject of the film is the Cool Hand Luke production apparatus and the people working behind the camera. The scene being photographed for their movie is a sequence with about 15 shirtless convicts working at the side of a hot black tar road with shovels. Sand is tossed on the road until it is covered. Then they move farther down the road. Shotgun carrying guards oversee their work at all times. The set itself has a representation of military and police officers as well as a highway motorcycle policeman. The actors (Paul Newman, Dennis Hopper, Harry Dean Stanton, George Kennedy etc.) are seen in front and behind the camera that is shooting the movie. The event becomes a stop and go parade since the entire crew and equipment must also be moved down the road to continue filming the continuity of dialogue and action. The final shot is a view of the actors moving their shovels as if they are tossing the sand on the road but the shovels are empty. The original running time for the regular 8mm film would be about 2.5 minutes. The final digital edit of the film to tape transfer in 2004 (with original music by Patrick Gleeson) is longer because each picture frame last one third of a second: there are 3 images per second. It has the character of both a motion picture and a series of still photos. The filming with the hand-held camera created immediate edits in the camera with regular 8mm speed (18 frames per second) as well as one frame at a time. (Bruce Conner)

Back to top

Date: 31 October 2004 | Season: London Film Festival 2004 | Tags: London Film Festival

LOS ANGELES PLAYS ITSELF

Sunday 31 October 2004, at 12pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

Thom Andersen, Los Angeles Plays Itself, USA, 2003, 169 min

A remarkable documentary about cinema, an endlessly fascinating visual lecture and an important social commentary, Thom Andersen’s love letter to Los Angeles explores the city’s representation on film. With its relentless, mesmerising montage of clips and archive footage, the film explores how the Western centre of the film industry is actually portrayed on-screen. Divided into chapters that treat Los Angeles as – amongst other things – background, character and subject, the film revisits crucial landmarks (the steps up which Laurel & Hardy attempted to manoeuvre a piano in The Music Box, explores famous buildings (the Spanish Revival house in Double Indemnity, the cavernous Bradbury Building made famous by Blade Runner), and charts the city’s ‘secret’ history through such films as Chinatown, L.A. Confidential and Who Framed Roger Rabbit. As comfortable with softcore exploitation as it is with the avant-garde, Los Angeles Plays Itself is a cinematic treasure trove that makes one think again about a city that – as a movie location – has never seemed quite as romantic or exciting as New York. Indeed, the world around you may seem more mysterious and compelling after almost three hours well spent in Andersen’s company. And you’ll definitely never refer to Los Angeles as ‘L.A.’ again. (David Cox)

Also Screening: Thursday 28 October 2004, at 8:15pm London NFT1

PROGRAMME NOTES

LOS ANGELES PLAYS ITSELF

Sunday 31 October 2004, at 12pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

LOS ANGELES PLAYS ITSELF

Thom Andersen, USA, 2003, video, colour, sound, 169 min

Most movies are intended to transform documentary into fiction; Thom Andersen’s heady and provocative Los Angeles Plays Itself has the opposite agenda. This nearly three-hour “city symphony in reverse” analyses the way that Los Angeles has been represented in the movies.

Andersen, who teaches at Cal Arts, is the author of two previous, highly original film-historical documentaries – Eadweard Muybridge, Zoopraxographer and Red Hollywood (made with theoretician Noël Burch). A manifesto as well as a monument, Los Angeles Plays Itself has its origins in a clip lecture that Andersen originally “intended for locals only,” but as finished, it is an essay in film form with near-universal interest and a remarkable degree of synthesis. If Andersen’s dense montage and noirish, world-weary voice-over owe a bit to Mark Rappaport’s VCRchaeological digs, his methodology recalls the literary chapters in Mike Davis’s Los Angeles books City of Quartz and Ecology of Fear; no less than Pat O’Neill in The Decay of Fiction, but in a completely different fashion, he has found a way to turn Hollywood history to his own ends.

Digressive if not quite free-associational in his narrative, Andersen begins by detailing the effect that Hollywood has had on the world’s most photographed city – a metropolis where motels or McDonald’s might be constructed to serve as sets and “a place can become a historic landmark because it was once a movie location.” Andersen is steeped in Los Angeles architecture as well as motion pictures, and his thinking is habitually dialectical – the Spanish Revival house in Double Indemnity, which Andersen admires, turns up as another sort of signifier in L.A. Confidential, the movie that inspired his critique (not least because Andersen has the same irritated disdain for the nickname “L.A.” that San Franciscans have for “Frisco”).

With a complex nostalgia for the old Los Angeles and a far-ranging knowledge of its indigenous cinema, Andersen draws on avant-garde and exploitation films as well as studio products. In his first section, “The City as Background,” he wonders why the city’s modern architecture is typically associated with gangsters. (Producers may actually live in these houses, but, as is often the case in Hollywood, “conventional ideology trumps personal conviction.”) Andersen ponders the guilty pleasure of destroying Los Angeles, but he’s most fond of those “literalist” films that preserve, however inadvertently, or at least recognise the city’s geography: Kiss Me Deadly (with its extensive shooting in lost Bunker Hill) and Rebel Without a Cause (in which locations are shot as though they were studio sets).

Andersen goes on to discuss Los Angeles as a “character,” beginning with the city’s transformation, by hard-boiled novelists Raymond Chandler and James M. Cain, into “the world capital of adultery and murder.” The movie’s latter half is devoted to Los Angeles as subject, starting with the self-conscious urban legend of Chinatown and considering other movies – Who Framed Roger Rabbit, L. A. Confidential – that provide the city’s imaginary secret history. A disquisition on the on-screen evolution of Los Angeles cops in the 1990s leads Andersen to the African American filmmakers Charles Burnett and Billy Woodberry, who, in their neo-neorealism, provide the antithesis of movie mystification and studio fakery.

(Jim Hoberman, Village Voice)

Back to top