Date: 12 March 2002 | Season: Andy Warhol Tate

SUNSET + IMITATION OF CHRIST

Tuesday 12 March 2002, at 6:30pm

London Tate Modern

Sections from the 25-hour double screen movie ****.

Andy Warhol, Sunset, USA, 1967, 33 min

Andy Warhol, Imitation of Christ, USA, 1967-69, 85 min

Warhol’s recording of a beautiful California sunset was one of an unfinished series commissioned by art patrons Jean and Dominique de Menil, and visually echoes their Rothko Chapel. Nico reads poetry on the soundtrack. Imitation of Christ is a domestic comedy about a strange but beautiful young man who wanders through life oblivious to the complaints of his parents (Ondine and Brigid Polk) and the attempted seductions of his maid (Nico), his girlfriend (Andrea “Whips” Feldman) and the riotous antics of Taylor Mead. Edited down to feature-length from the 6-hour version included in Warhol’s 25-hour double screen film **** (1967).

Date: 17 March 2002 | Season: Andy Warhol Tate

POOR LITTLE RICH GIRL + LUPE

Sunday 17 March 2002, at 3:00pm

London Tate Modern

At home with Edie Sedgwick.

Andy Warhol, Poor Little Rich Girl, USA, 1965, 33 min (double screen)

Andy Warhol, Lupe, USA, 1965, 73 min

Warhol spoke of filming twenty-four hours in the life of Edie Sedgwick and these two films may have formed part of the project. Each shows the 1965 Girl of the Year at home, waking up, applying make-up, getting dressed. One reel of Poor Little Rich Girl is inexplicably, but doubtless intentionally, out of focus. Lupe, shot in sumptuous colour, alludes to a re-enactment of the tragic death of actress Lupe Velez, as Edie ends each reel slumped over a toilet bowl.

Date: 19 March 2002 | Season: Andy Warhol Tate

THE CLOSET + SALVADOR DALI + THE VELVET UNDERGROUND & NICO

Tuesday 19 March 2002, at 6:30pm

London Tate Modern

The Velvet Underground and Nico special programme

Andy Warhol, The Closet, USA, 1965, 66 min

Andy Warhol, Salvador Dali, USA, 1966, 22 min

Andy Warhol, The Velvet Underground & Nico, USA, 1966, 33 min (double screen)

For reasons which are not explained, Femme Fatale Nico and shy Randy Bourscheidt are two people living inside The Closet. The newly discovered Salvador Dali reel was used as a background to performances of the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, and consists of several Screen Tests and the legendary Whip Dance to accompany “Venus in Furs”. The Velvet Underground & Nico shows the band rehearsing in the Factory, playing a unique extended improvisation which is eventually broken up by the New York Police Department.

Date: 21 March 2002 | Season: Andy Warhol Tate

ANDY WARHOL’S SILVER FACTORY

Thursday 21 March 2002, at 8:00pm

London The Scala

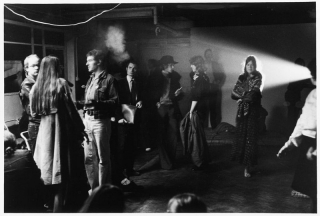

An expanded cinema event with films, music and dancing. Several Warhol films will be shown, including a double screen projection of The Chelsea Girls.

Andy Warhol, The Chelsea Girls, USA, 1966, 210 min (double screen)

Warhol’s magnum opus that brought the avant-garde into commercial movie theatres. The two-screen format is used to depict simultaneous events indifferent rooms of the Chelsea Hotel, playing psychological situations against each other. The Factory Superstars, including “Pope” Ondine, Brigid Polk, Mary Woronov and Eric Emerson turn in extraordinary performances in this fascinating observation of New York’s subculture. Sex, drugs and divinity, with exclusive music by The Velvet Underground.

Also screening other Warhol films and footage to include Vinyl (1965), The Velvet Underground & Nico (1966) and Lupe (1965).

Action on many levels with Superstar DJs including David Holmes, Bob Stanley/Pete Wiggs (St Etienne), Mark Webber (Pulp) and BBC Radio 3’s Richard Coles playing period pop, soul and opera.

Plus special guest live performances and interventions.

In association with Tate Magazine.

Date: 24 March 2002 | Season: Andy Warhol Tate

BIKE BOY

Sunday 24 March 2002, at 3:00pm

London Tate Modern

Factory Sexploitation.

Andy Warhol, Bike Boy, USA, 1967-68, 109 min

The box office success of The Chelsea Girls provoked a significant change in the style of Warhol’s filmmaking, which moved towards a more commercial approach as Paul Morrissey took over production. The Bike Boy is Joe Spencer, a hick biker who is obviously out of his depth up against the fast-talking and extrovert Factory regulars Viva, Brigid Polk and Ingrid Superstar. One of a succession of sexploitation movies made throughout the late 60s.

Date: 17 April 2002 | Season: Infinite Projection

INFINITE PROJECTION

17 April–18 December 2002

London The Photographers’ Gallery

Despite a rich history and a dedicated, continuously expanding audience, an important area of the arts is being neglected in our capital city. No venue in London is committed to showing artists’ film and video in its purest form, specific to its medium, truly independent. The arts centres, galleries, colleges and museums are not our advocates, institutions are failing us.

There’s heart and passion, but no hub. Infinite Projection does not aspire to be that centre, more a satellite cell. A meeting point, a principle, an impulse, a SCREEN. A starting point for further action and a statement of intent. They tell us film is dead, but they haven’t eradicated us yet. Film is thriving and we are digging in, powerful and resolute, here for the DURATION, shining forth into infinity.

Infinite Projection is presented by Mark Webber and co-ordinated by Lisa Le Feuvre.

Thank you Ben Cook & Mike Sperlinger, David Leister, Michael Zimmerman, Stefanie Schuldt Strathaus & Karl Winter, Deirdre Logue & the Canadian Filmmakers’ Distribution Centre, Christophe Bichon, Barbara Pichler & Brigitta Burger-Utzer, Dominic Angerame, Michael Sippings, Rob Gawthrop, Hogge, Paola Igliori and Jonathan Swain

Films and videos distributed by Anthology Film Archives (New York), Lightcone (Paris), Collectif Jeune Cinema (Paris), Fringe Films (Toronto), Lux (London), Film Form (Stockholm), Filmmakers’ Information Centre (Tokyo), Canyon Cinema (San Francisco), Video Data Bank (Chicago).

Supported by the Arts Council of England’s DNet exhibition screenings 2002 and assisted by LUX. Supported by London Film & Video Development Agency.

Date: 17 April 2002 | Season: Infinite Projection

GUSTAV DEUTSCH: FILM IST 1-6

Wednesday 17 April 2002, at 7:30pm

London The Photographers’ Gallery

Drawing on a vast accumulation of material from archives throughout the world, Deutsch multiplies content against form to magnify the power of each image, and presents a rigorous and entertaining exposition of film’s unique qualities. The initial six sections of this tableaux film focus primarily on scientific and medical footage concerning the birth of cinema and the phenomena of sight and perception.

Gustav Deutsch, Film Ist 1-6, 1998, 60 min

Thomas Draschan, Metropolen des Leichtsinns, 2000, 12 min

The screening of Film Ist 1-6 is supported by the Austrian Cultural Forum.

PROGRAMME NOTES

GUSTAV DEUTSCH: FILM IST 1-6

Wednesday 17 April 2002, at 7:30pm

London The Photographers’ Gallery

FILM IST 1-6

Gustav Deutsch, Austria, 1998, colour, sound, 60 min

“Film Ist consists, almost exclusively, of sequences from existing scientific films. These films are about the acrobatic flights of pigeons, the intelligence testing of apes; about ‘reversed worlds’ and stereoscopic vision; hurricanes and impact waves in the air. They depict paper projectiles penetrating bubbles of air and bullets passing through ostrich eggs. They concern the dynamics of the diaphragm as one breathes, sings or makes music. They show how glass breaks, children walk and how a Mercedes Benz crashes into a stone wall in slow motion.

“As with all images which issue from the area of the natural sciences, scientific films almost always follow a special educational line – they address the viewer as a beneficiary of their discoveries and thus, in a wider sense, as a patient. They attempt to create the ideal, insightful, patient. In order to be comprehensible and convincing outside of their specialist sphere they do not present the arguments in scientific language (mathematics) but detour into the world of aesthetics. Here they encounter other conventions – visual, narrative and poetic. The collective ‘aesthetic knowledge’ stored in these conventions lends form to the scientific knowledge.

“And this a kind of ‘ideography’ is created which almost everyone has learned to read during their school days or from school television. But I think this process contributes more to cinematographic education than to the scientific. The contempt with which scientific films are received is not directed against the content, but rather against their conventional, unimaginative, ridiculous and commentary-contaminated appearance. Similarly, the fascination with some teaching films, which is certainly less common, can be attributed almost exclusively to the power of their imagination – images which one has never seen, even in the cinema.”

(Alexander Horwath, Austrian Film Archive, Vienna)

METROPOLEN DES LEICHTSINNS

Thomas Draschan, Germany, 2000, colour, sound, 12 min

Found-footage collides together to consider the lifestyle options of modern man.

Back to top

Date: 1 May 2002 | Season: Shoot Shoot Shoot 2002 | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT: THE FIRST DECADE OF THE LONDON FILM-MAKERS’ COOPERATIVE & BRITISH AVANT-GARDE FILM 1966-76

3 May–28 May 2002

London Tate Modern

The London Film-Makers’ Co-operative was founded in 1966 and based upon the artist-led distribution centre created by Jonas Mekas and the New American Cinema Group. Both had a policy of open membership, accepting all submissions without judgement, but the LFMC was unique in incorporating the three key aspects of artist filmmaking: production, distribution and exhibition within a single facility.

Early pioneers like Len Lye, Antony Balch, Margaret Tait and John Latham had already made remarkable personal films in Britain, but by the mid-60s interest in “underground” film was growing. On his arrival from New York, Stephen Dwoskin demonstrated and encouraged the possibilities of experimental filmmaking and the Co-op soon became a dynamic centre for the discussion, production and presentation of avant-garde film. Several key figures such as Peter Gidal, Malcolm Le Grice, John Smith and Chris Welsby went onto become internationally celebrated. Many others, like Annabel Nicolson and the fiercely autonomous and prolific Jeff Keen, worked across the boundaries between film and performance and remain relatively unknown, or at least unseen.

The Co-op asserted the significance of the British films in line with international developments, whilst surviving hand-to-mouth in a series of run down buildings. The physical hardship of the organisation’s struggle contributed to the rigorous, formal nature of films produced during this period. While the Structural approach dominated, informing both the interior and landscape tendencies, the British filmmakers also made significant innovations with multi-screen films and expanded cinema events, producing works whose essence was defined by their ephemerality. Many of the works fell into the netherworld between film and fine art, never really seeming at home in either cinema or gallery spaces.

“What follows is a set of instructions, necessarily incomplete, for the construction, necessarily impossible, of a mosaic. Each instruction must lead to the screen, the tomb and temple in which the mosaic grows. The instructions are fractured but not frivolous. They are no more than clues to the films which lust for freedom and re-illumination with, by and of the cinema. What follows is not truth, only evidence. The explanation is in the projection and the perception.” —Simon Hartog, 1968

“It is often difficult for a venue organiser/programmer to determine from written description what an individual or group of film-makers work is ‘about’, from where it comes, to what or whom it is addressing itself. Equally, it is difficult for a film-maker to provide such information from within the pages of a catalogue when for many, including myself, the entire project or the area into which one’s work energy is concentrated, is intent on clarifying these kind of questions. The films outside of such a situation become more or less dead objects, the residue (though hopefully a determined residue) of such an all-embracing pursuit.” —Mike Leggett, 1980

“The most important thing still is to let oneself get into the film one is watching, to stop fighting it, to stop feeling the need to object during the process of experience, or rather, to object, fight it, but overcome each moment again, to keep letting oneself overcome one’s difficulties, to then slide into it (one can always demolish the experience afterwards anyway, so what’s the hurry?).” —Peter Gidal, c.1970-71

Shoot Shoot Shoot, a major retrospective programme and research project, will bring these extraordinary works back to life.

Curated by Mark Webber with assistance from Gregory Kurcewicz and Ben Cook.

Shoot Shoot Shoot is a LUX project. Funded by the Arts Council of England National Touring Programme, the British Council, BFI and the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation.

Date: 1 May 2002 | Season: Infinite Projection | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

JEFF KEEN

Wednesday 1 May 2002, at 7:30pm

London The Photographers’ Gallery

A special Mayday Rayday expanded cinema performance to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the first Rayday broadsheet. Using 8mm, 16mm and video, Jeff Keen bridges the gap between 1969’s Raydayfilm and his recent Artwar: The Last Frontier. A unique and spontaneous mixed-media collage from Britain’s first and most productive independent filmmaker.

Jeff Keen, From Raydayfilm to Artwar, UK, 1969-2002, colours, sounds, c.70 min (multi-media performance)

“Keen is indebted to the Surrealist tradition for many of his central concerns: his passion for instability, his sense of le merveilleux, his fondness for analogies and puns, his preference for ‘lowbrow’ art over aestheticism of any kind, his dedication to collage and le hazard objectif. But this ‘continental’ facet of his work – virtually unique in this country – co-exists with various typically English characteristics, which betray other roots. The tacky glamour/true beauty of his Family Star productions is at least as close to the end of Brighton pier as it is to Hollywood B-movies… The heroic absurdity and adult infantilism that are the mainsprings of his comedy draw on a long tradition of post-Victorian humour: not the ‘innocent’ vulgarity of music hall, but the anarchicness of The Goons and the self-lacerating ironies of the 30s clowns, complete with their undertow of melancholia.” (Tony Rayns, “Born to Kill: Mr. Soft Eliminator”, Afterimage No. 6, 1976)

This event is related to the Shoot Shoot Shoot season at Tate Modern throughout May 2002.

Back to top

Date: 3 May 2002 | Season: Shoot Shoot Shoot 2002 | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

EXPANDED CINEMA

Friday 3 May 2002, at 7:30pm

London Tate Modern Level 7 East

British filmmakers led a drive beyond the screen and the theatre, and their innovations in expanded cinema inevitably took the work into galleries. After questioning the role of the spectator, they began to examine the light beam, its volume and presence in the room.

Malcolm Le Grice, Castle One, 1966, b/w, sound, 20 min

William Raban, Take Measure, 1973, colour, silent, 2 min

William Raban, Diagonal, 1973, colour, sound, 6 min

Gill Eatherley, Hand Grenade, 1971, colour, sound, 8 min

Lis Rhodes, Light Music, 1975-77, b/w, sound, 20 min

Anthony McCall, Line Describing A Cone, 1973, b/w, silent, 30 min

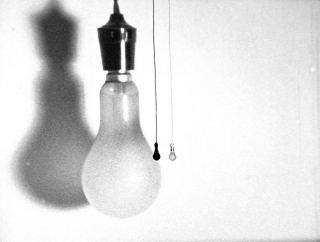

In a step towards later complex projection pieces, for Castle One, Malcolm Le Grice hung a light bulb in front of the screen. Its intermittent flashing bleaches out the image, illuminates the audience and lays bare the conditions of the traditional screening arrangement. Take Measure, by William Raban, visually measures a dimension of the space as the filmstrip is physically stretched between projector and screen. To make Diagonal, he directly filmed into the projector gate and presents the same flickering footage in dialogue across three screens in an oblique formation. Gill Eatherley literally painted in light over extremely long exposures to shoot Hand Grenade, which runs three different edits of the material side-by-side. Light Music developed into a series of enquiries into the nature of optical soundtracks and their direct relation to the abstract image. The film can be shown in different configurations, with projectors side-by-side or facing into each other. Anthony McCall succinctly demonstrates the sculptural potential of film as a single ray of light, incidentally tracing a circle on the screen, is perceived as a conical line emanating from the projector. The beam is given physical volume in the room by use of theatrical smoke, or any other agent (such as dust) that would thicken the air to make it more apparent. More than just a film, Line Describing a Cone affirms cinema as a collective social experience.

Screening introduced by William Raban and Anthony McCall.

Programme repeated on Monday 6 May 2002, at 7:30pm

PROGRAMME NOTES

EXPANDED CINEMA

Friday 3 May 2002, at 7:30pm

London Tate Modern Level 7 East

CASTLE ONE

Malcolm Le Grice, 1966, b/w, sound, 20 min

“The light bulb was a Brechtian device to make the spectator aware of himself. I don’t like to think of an audience in the mass, but of the individual observer and his behaviour. What he goes through while he watches is what the film is about. I’m interested in the way the individual constructs variety from his perceptual intake.” —Malcolm Le Grice, Films and Filming, February 1971

“… totally Kafkaesque, but also filmically completely different from anyone else because of the rawness. The Americans are always talking about ‘rawness’, but it’s never raw. When the English talk about ‘raw’, they don’t just talk about it, it really is raw – it’s grey, it’s rainy, it’s grainy, you can hardly see what’s there. The material really is there at the same time as the image. With the Germans, it’s a high-class image of material, optically reproduced and glossy. The Americans are half-way there, but the English stuff looked like it really was home-made, artisanal, and yet amazingly structured. And I certainly thought Castle One was the most powerful film I’d seen, ever…” —Peter Gidal, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

“Malcolm said to me “Ideally in this film there should be a real light bulb hanging next to the screen, but that’s not possible.” And I said “It’s not possible to hang a light bulb?” He said “Well, I don’t see how we could possibly do this.” I said “Well the only question is how do we turn it on and off at the right moments? … Are you able to do that as a live performance?” He looked at me like the world was going to end! And I said “The switch will be there.”” —Jack Moore, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

TAKE MEASURE

William Raban, 1973, colour, silent, 2 min

“The thing that strikes me going into a cinema, because it is such a strange space and it’s organized to allow you to get enveloped by the whole illusion of film, when you try and think of it in terms of real dimensions it becomes very difficult. The idea of a sixty foot throw or a hundred foot throw from the projector to the screen just doesn’t enter into the equation. So I thought the idea of making a piece that made that distance between the projector and the screen more tangible was quite an interesting thing to do.” —William Raban, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

“Take Measure is usually the shortest of my films, measuring in feet that intangible space separating screen from projector box (which is counted on the screen by the image of a film synchronizer). Instead of being fed into the projector from a reel, the film is strung between projector and screen. When the film starts, the film snakes backwards through the audience as it is consumed by the projector.” —William Raban, Perspectives on British Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1977

DIAGONAL

William Raban, 1973, colour, sound, 6 min

“Diagonal is a film for three projectors, though the diagonally arranged projector beams need not be contained within a single flat screen area. This film works well in a conventional film theatre when the top left screen spills over the ceiling and the bottom right projects down over the audience. It is the same image on all three projectors, a double-exposed flickering rectangle of the projector gate sliding diagonally into and out of frame. Focus is on the projector shutter, hence the flicker. This film is ‘about’ the projector gate, the plane where the film frame is caught by the projected light beam.” —William Raban, Perspectives on British Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1977

“The first great excitement is finding the idea, making its acquaintance, and courting it through the elaborate ritual of film production. The second excitement is the moment of projection when the film becomes real and can be shared with the audience. The former enjoyment is unique and privileged; the second is not, and so long as the film exists, it is infinitely repeatable.” —William Raban, Arts Council Film-Makers on Tour catalogue, 1980

HAND GRENADE

Gill Eatherley, 1971, colour, sound, 8 min

“Although the word ‘expanded’ cinema has also been used for the open/gallery size/multi screen presentation of film, this ‘expansion’ (could still but) has not yet proved satisfactory – for my own work anyway. Whether you are dealing with a single postcard size screen or six ten-foot screens, the problems are basically the same – to try to establish a more positively dialectical relationship with the audience. I am concerned (like many others) with this balance between the audience and the film – and the noetic problems involved.” —Gill Eatherley, 2nd International Avant-Garde Film Festival programme notes, 1973

“Malcolm Le Grice helped me with Hand Grenade. First of all I did these stills, the chairs traced with light. And then I wanted it to all move, to be in motion, so we started to use 16mm. We shot only a hundred feet on black and white. It took ages, actually, because it’s frame by frame. We shot it in pitch dark, and then we took it to the Co-op and spent ages printing it all out on the printer there. This is how I first got involved with the Co-op.” —Gill Eatherley, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

LIGHT MUSIC

Lis Rhodes, 1975-77, b/w, sound, 20 min

“Lis Rhodes has conducted a thorough investigation into the relationship between the shapes and rhythms of lines and their tonality when printed as sound. Her work Light Music is in a series of ‘moveable sections’. The film does not have a rigid pattern of sequences, and the final length is variable, within one-hour duration. The imagery is restricted to lines of horizontal bars across the screen: there is variety in the spacing (frequency), their thickness (amplitude), and their colour and density (tone). One section was filmed from a video monitor that produced line patterns on the screen that varied according to sound signals generated by an oscillator; so initially it is the sound which produces the image. Taking this filmed material to the printing stage, the same lines that produced the picture are printed onto the optical soundtrack edge of the film: the picture thus produces the sound. Other material was shot from a rostrum camera filming black and white grids, and here again at the printing stage, the picture is printed onto the film soundtrack. Sometimes the picture ‘zooms’ in on the grid, so that you actually ‘hear’ the zoom, or more precisely, you hear an aural equivalent to the screen image. This equivalence cannot be perfect, because the soundtrack reproduces the frame lines that you don’t see, and the film passes at even speed over the projector sound scanner, but intermittently through the picture gate. Lis Rhodes avoids rigid scoring procedures for scripting her films. This work may be experienced (and was perhaps conceived) as having a musical form, but the process of composition depends on various chance operations, and upon the intervention of the filmmaker upon the film and film machinery. This is consistent with the presentation where the film does not crystallize into one finished form. This is a strong work, possessing infinite variety within a tightly controlled framework.” —William Raban, Perspectives on British Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1977

“The film is not complete as a totality; it could well be different and still achieve its purpose of exploring the possibilities of optical sound. It is as much about sound as it is about image; their relationship is necessarily dependent as the optical soundtrack ‘makes’ the music. It is the machinery itself which imposes this relationship. The image throughout is composed of straight lines. It need not have been.” —Lis Rhodes, A Perspective on English Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1978

LINE DESCRIBING A CONE

Anthony McCall, 1973, b/w, silent, 30 min

“Once I started really working with film and feeling I was making films, making works of media, it seemed to me a completely natural thing to come back and back and back, to come more away from a pro-filmic event and into the process of filmmaking itself. And at the time it all boiled down to some very simple questions. In my case, and perhaps in others, the question being something like “What would a film be if it was only a film?” Carolee Schneemann and I sailed on the SS Canberra from Southampton to New York in January 1973, and when we embarked, all I had was that question. When I disembarked I already had the plan for Line Describing a Cone fully-fledged in my notebook. You could say it was a mid-Atlantic film! It’s been the story of my life ever since, of course, where I’m located, where my interests are, that business of “Am I English or am I American?” So that was when I conceived Line Describing a Cone and then I made it in the months that followed.” —Anthony McCall, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

“One important strategy of expanded cinema radically alters the spatial discreteness of the audience vis-à-vis the screen and the projector by manipulating the projection facilities in a manner which elevates their role to that of the performance itself, subordinating or eliminating the role of the artist as performer. The films of Anthony McCall are the best illustration of this tendency. In Line Describing a Cone, the conventional primacy of the screen is completely abandoned in favour of the primacy of the projection event. According to McCall, a screen is not even mandatory: The audience is expected to move up and down, in and out of the beam – this film cannot be fully experienced by a stationary spectator. This means that the film demands a multi-perspectival viewing situation, as opposed to the single-image/single-perspective format of conventional films or the multi-image/single-perspective format of much expanded cinema. The shift of image as a function of shift of perspective is the operative principle of the film. External content is eliminated, and the entire film consists of the controlled line of light emanating from the projector; the act of appreciating the film – i.e., ‘the process of its realisation’ – is the content.” —Deke Dusinberre, “On Expanding Cinema”, Studio International, November/December 1975

Back to top