Beginning in the 1960s, artists at the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative experimented with multiple projection, live performance and film environments. In liberating cinema from traditional theatrical presentation, they broke down the barrier between screen and audience, and extended the creative act to the moment of exhibition. “Shoot Shoot Shoot” presents historic works of Expanded Cinema, for which each screening is a unique, collective experience, in stark contrast to contemporary video installations. In Line Describing a Cone, a film projected through smoke, light becomes an apparently solid, sculptural presence, whilst other works for multiple projection create dynamic relationships between images and sounds.

Curated by Mark Webber. Presented in association with LUX.

SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT: EXPANDED CINEMA

Wednesday 23 May 2007, at 7PM

Wrexham Arts Centre

EXPANDED CINEMA at the LONDON FILM-MAKERS’ CO-OPERATIVE

Expanded Cinema is a term used to describe works that do not confirm to the traditional single-screen cinema format. It could mean having two (or more) images side-by-side on the screen, films that incorporate live performances or are projected in an unorthodox manner without a screen. Even light pieces that do not use any film at all. Some work demands that the filmmaker interact with the projected image, or be behind the projectors to alter their configuration throughout the screening.

The London Film-Makers’ Co-operative was an artist-led organisation formed in 1966, and uniquely incorporated a distribution office, workshop laboratory and screening room. Expanded Cinema continued the analytical exploration of the material that was conducted by filmmakers in the workshop, and emphasised the transient nature of the medium.

The Co-op’s cinema space was a flat, open room with no fixed seating. Filmmakers were free to experiment with projectors, demonstrating that the moment of exhibition can be as much a part of the work as the original concept, filming, editing and processing. The technology that puts the illusion of movement onscreen was no longer hidden away in a projection booth behind the audience, but placed amongst them.

In questioning the role of the spectator, Expanded Cinema challenged the conventions of the cinema event and introduced elements of chance and improvisation. Sometimes, what happened across the room was more important than what was up on the screen. With such work no two projections were ever the same: each screening was a unique, social, collective experience for the assembled audience.

This drive beyond the screen and theatre inevitably took the work into galleries, but only as a practical measure since open spaces and white walls were ideal for unconventional projection. The filmmakers made no attempts to commodify their work by producing editions, for many it was against their socialist principles. Though Expanded Cinema anticipated many recent trends in gallery-based moving image works and installations, there was little acceptance from the art world in the early years, or acknowledgement of this groundbreaking work today.

Mark Webber

CASTLE TWO

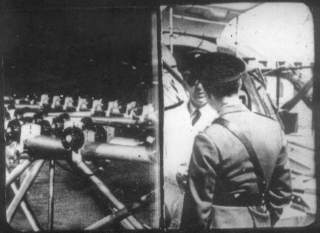

Malcolm Le Grice, 1968, b/w, sound, 32 min (2 screens)

“This film continues the theme of the military/industrial complex and its psychological impact upon the individual that I began with Castle One. Like Castle One, much use is made of newsreel montage, although with entirely different material. The film is more evidently thematic, but still relies on formal devices – building up to a fast barrage of images (the two screens further split – to give 4 separate images at once for one sequence). The images repeat themselves in different sequential relationships and certain key images emerge both in the soundtrack and the visual. The alienation of the viewer’s involvement does not occur as often in this film as in Castle One, but the concern with the viewer’s experience of his present location still determines the structure of certain passages in the film.” —Malcolm Le Grice, London Film-Makers’ Co-operative catalogue, 1968

“Le Grice’s work induces the observer to participate by making him reflect critically not only on the formal properties of film but also on the complex ways in which he perceives that film within the limitations of the environment of its projection and the limitations created by his own past experience. A useful formulation of how this sort of feedback occurs is contained in the notion of ‘perceptual thresholds’. Briefly, a perceptual threshold is demarcation point between what is consciously and what is pre-consciously perceived. The threshold at which one is able to become conscious of external stimuli is a variable that depends on the speed with which the information is being projected, the emotional charge it contains and the general context within which that information is presented. This explains Le Grice’s continuing use of devices such as subliminal flicker and the looped repetition of sequences in a staggered series of changing relationships.” —John Du Cane, Time Out, 1977

PLAY

Sally Potter, 1971, b/w & colour, silent, 7 min (2 screens)

“In Play, Potter filmed six children – actually, three pairs of twins – as they play on a sidewalk, using two cameras mounted so that they recorded two contiguous spaces of the sidewalk. When Play is screened, two projectors present the two images side by side, recreating the original sidewalk space, but, of course, with the interruption of the right frame line of the left image and the left frame line of the right image – that is, so that the sidewalk space is divided into two filmic spaces. The cinematic division of the original space is emphasized by the fact that the left image was filmed in color, the right image in black and white. Indeed, the division is so obvious that when the children suddenly move from one space to the other, ‘through’ the frame lines, their originally continuous movement is transformed into cinematic magic.” —Scott MacDonald, A Critical Cinema 3, 1998)

“To be frank, I always felt like a loner, an outsider. I never felt part of a community of filmmakers. I was often the only female, or one of few, which didn’t help. I didn’t have a buddy thing going, which most of the men did. They also had rather different concerns, more hard-edged structural concerns … I was probably more eclectic in my taste than many of the English structural filmmakers, who took an absolute prescriptive position on film. Most of them had gone to Oxford or Cambridge or some other university and were terribly theoretical. I left school at fifteen. I was more the hand-on artist and less the academic. The overriding memory of those early years is of making things on the kitchen table by myself…” —Sally Potter interviewed by Scott MacDonald, A Critical Cinema 3, 1998

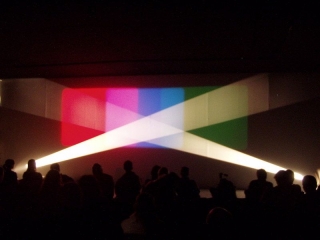

DIAGONAL

William Raban, 1973, colour, sound, 6 min (3 screens)

“Diagonal is a film for three projectors, though the diagonally arranged projector beams need not be contained within a single flat screen area. This film works well in a conventional film theatre when the top left screen spills over the ceiling and the bottom right projects down over the audience. It is the same image on all three projectors, a double-exposed flickering rectangle of the projector gate sliding diagonally into and out of frame. Focus is on the projector shutter, hence the flicker. This film is ‘about’ the projector gate, the plane where the film frame is caught by the projected light beam.” —William Raban, Perspectives on British Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1977

“The first great excitement is finding the idea, making its acquaintance, and courting it through the elaborate ritual of film production. The second excitement is the moment of projection when the film becomes real and can be shared with the audience. The former enjoyment is unique and privileged; the second is not, and so long as the film exists, it is infinitely repeatable.” —William Raban, Arts Council Film-Makers on Tour catalogue, 1980

HAND GRENADE

Gill Eatherley, 1971, colour, sound, 8 min (3 screens)

“Although the word ‘expanded’ cinema has also been used for the open/gallery size/multi screen presentation of film, this ‘expansion’ (could still but) has not yet proved satisfactory – for my own work anyway. Whether you are dealing with a single postcard size screen or six ten-foot screens, the problems are basically the same – to try to establish a more positively dialectical relationship with the audience. I am concerned (like many others) with this balance between the audience and the film – and the noetic problems involved.” —Gill Eatherley, 2nd International Avant-Garde Film Festival programme notes, 1973

“Malcolm Le Grice helped me with Hand Grenade. First of all I did these stills, the chairs traced with light. And then I wanted it to all move, to be in motion, so we started to use 16mm. We shot only a hundred feet on black and white. It took ages, actually, because it’s frame by frame. We shot it in pitch dark, and then we took it to the Co-op and spent ages printing it all out on the printer there. This is how I first got involved with the Co-op.” —Gill Eatherley, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

LIGHT MUSIC

Lis Rhodes, 1975-77, b/w, sound, 20 min (2 screens)

“Lis Rhodes has conducted a thorough investigation into the relationship between the shapes and rhythms of lines and their tonality when printed as sound. Her work Light Music is in a series of ‘moveable sections’. The film does not have a rigid pattern of sequences, and the final length is variable, within one-hour duration. The imagery is restricted to lines of horizontal bars across the screen: there is variety in the spacing (frequency), their thickness (amplitude), and their colour and density (tone). One section was filmed from a video monitor that produced line patterns on the screen that varied according to sound signals generated by an oscillator; so initially it is the sound which produces the image. Taking this filmed material to the printing stage, the same lines that produced the picture are printed onto the optical soundtrack edge of the film: the picture thus produces the sound. Other material was shot from a rostrum camera filming black and white grids, and here again at the printing stage, the picture is printed onto the film soundtrack. Sometimes the picture ‘zooms’ in on the grid, so that you actually ‘hear’ the zoom, or more precisely, you hear an aural equivalent to the screen image. This equivalence cannot be perfect, because the soundtrack reproduces the frame lines that you don’t see, and the film passes at even speed over the projector sound scanner, but intermittently through the picture gate. Lis Rhodes avoids rigid scoring procedures for scripting her films. This work may be experienced (and was perhaps conceived) as having a musical form, but the process of composition depends on various chance operations, and upon the intervention of the filmmaker upon the film and film machinery. This is consistent with the presentation where the film does not crystallize into one finished form. This is a strong work, possessing infinite variety within a tightly controlled framework.” —William Raban, Perspectives on British Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1977

“The film is not complete as a totality; it could well be different and still achieve its purpose of exploring the possibilities of optical sound. It is as much about sound as it is about image; their relationship is necessarily dependent as the optical sound track ‘makes’ the music. It is the machinery itself which imposes this relationship. The image throughout is composed of straight lines. It need not have been.” —Lis Rhodes, A Perspective on English Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1978

LINE DESCRIBING A CONE

Anthony McCall, 1973, b/w, silent, 30 min (1 screen, smoke)

“Once I started really working with film and feeling I was making films, making works of media, it seemed to me a completely natural thing to come back and back and back, to come more away from a pro-filmic event and into the process of filmmaking itself. And at the time it all boiled down to some very simple questions. In my case, and perhaps in others, the question being something like “What would a film be if it was only a film?” Carolee Schneemann and I sailed on the SS Canberra from Southampton to New York in January 1973, and when we embarked, all I had was that question. When I disembarked I already had the plan for Line Describing a Cone fully-fledged in my notebook. You could say it was a mid-Atlantic film! It’s been the story of my life ever since, of course, where I’m located, where my interests are, that business of “Am I English or am I American?” So that was when I conceived Line Describing a Cone and then I made it in the months that followed.” —Anthony McCall, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

“One important strategy of expanded cinema radically alters the spatial discreteness of the audience vis-à-vis the screen and the projector by manipulating the projection facilities in a manner which elevates their role to that of the performance itself, subordinating or eliminating the role of the artist as performer. The films of Anthony McCall are the best illustration of this tendency. In Line Describing a Cone, the conventional primacy of the screen is completely abandoned in favour of the primacy of the projection event. According to McCall, a screen is not even mandatory: The audience is expected to move up and down, in and out of the beam – this film cannot be fully experienced by a stationary spectator. This means that the film demands a multi-perspectival viewing situation, as opposed to the single-image/single-perspective format of conventional films or the multi-image/single-perspective format of much expanded cinema. The shift of image as a function of shift of perspective is the operative principle of the film. External content is eliminated, and the entire film consists of the controlled line of light emanating from the projector; the act of appreciating the film – i.e., ‘the process of its realisation’ – is the content.” —Deke Dusinberre, “On Expanding Cinema”, Studio International, November/December 1975

Back to top