Date: 25 May 2008 | Season: Videoex 2008

COUNTERCULTURE: LONDON IN THE SIXTIES

Sunday 25 May 2008, at 12pm

Zurich Videoex Festival Cinema Z3

After The Beatles shook the nation out of the cultural dark ages, Swinging London was the place to be. Prompted by the example of the American Beats, English experimenters and creative rebels challenged the conventions of art, music, literature, filmmaking and society itself.

The Boyle Family, Poem for Hoppy, 1967, 16mm on video, colour, sound, 4 min

Peter Whitehead, Wholly Communion, 1965, 16mm, b/w, sound, 32 min

Antony Balch & William Burroughs, Towers Open Fire, 1963, 16mm, b/w & colour, sound, 16 min

John Latham, Speak, 1968-69, 16mm, sound, colour, 11 min

James Scott, Richard Hamilton, 1969, 16mm, colour, sound, 25 min

PROGRAMME NOTES

COUNTERCULTURE: LONDON IN THE SIXTIES

Sunday 25 May 2008, at 12pm

Zurich Videoex Festival Cinema Z3

POEM FOR HOPPY

The Boyle Family, 1967, 16mm on video, colour, sound, 4 min

An improvised performance by Soft Machine and the Sensual Laboratory at the legendary UFO Club, in protest against John Hopkins’ excessive conviction for marijuana possession. (MW)

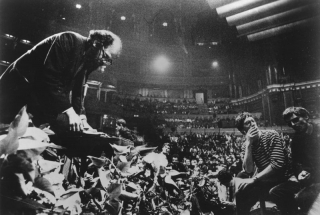

WHOLLY COMMUNION

Peter Whitehead, 1965, 16mm, b/w, sound, 32 min

The International Poetry Incarnation at the Royal Albert Hall started London’s sixties adventure. Whitehead’s crisply shot, half-hour film is remarkably comprehensive in documenting key performances of the evening, and captures the tangible sense of expectation that must have permeated the atmosphere within the cavernous concert hall. Wholly Communion not only encapsulates this seminal moment in which the underground went public, but remains one of the few records of a whole generation of poets performing in their prime. (MW)

TOWERS OPEN FIRE

Antony Balch, 1963, 16mm, colour, sound, 16 min

Envisioned as a cinematic realisation of Burroughs’ key themes such as the breakdown in control, the film contains rapid editing, flicker, strobing and extreme jump cuts that interrupt the narrative flow. The British Censor requested removal of some offensive language from the soundtrack but passed (or failed to recognise) the shots of Balch masturbating, and of Burroughs shooting up. (MW)

SPEAK

John Latham, 1968-69, 16mm, sound, colour, 11 min

Speak is his second attack on the cinema. Not since Len Lye’s films in the thirties has England produced such a brilliant example of animated abstraction. Speak burns its way directly into the brain. It is one of the few films about which it can truly be said, ‘it will live in your mind’. (Raymond Durgnat)

RICHARD HAMILTON

James Scott, 1969, 16mm, colour, sound, 25 min

Devoid of authoritative voiceover, the film presents samples of the artist’s work alongside reference materials, found footage, scenes from Hollywood features and news reports of the notorious Rolling Stones drugs trial. Bing Crosby, Marilyn Monroe and Patricia Knight (in Sirk and Fuller’s long forgotten Shockproof) also make appearances as the film traces the inspiration behind some of Hamilton’s signature paintings. (MW)

Back to top

Date: 27 May 2008 | Season: Videoex 2008 | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT: 1

Tuesday 27 May 2008, at 6pm

Zurich Videoex Festival Cinema Z3

The London Film-Makers’ Co-operative was established in 1966 to support work on the margins of art and cinema. It uniquely incorporated three related activities within a single organisation – a workshop for producing new films, a distribution arm for promoting them, and its own cinema space for screenings. In this environment, Co-op members were free to explore the medium and control every stage of the process. The Materialist tendency characterised the hardcore of British filmmaking in the early 1970s. Distinguished from Structural Film, these works were primarily concerned with duration and the raw physicality of the celluloid strip.

Annabel Nicolson, Slides, 1970, colour, silent, 11 mins (18fps)

Guy Sherwin, At the Academy, 1974, b/w, sound, 5 mins

Mike Leggett, Shepherd’s Bush, 1971, b/w, sound, 15 mins

David Crosswaite, Film No. 1, 1971, colour, sound, 10 mins

Lis Rhodes, Dresden Dynamo, 1971, colour, sound, 5 mins

Chris Garratt, Versailles I & II, 1976, b/w, sound, 11 mins

Mike Dunford, Silver Surfer, 1972, b/w, sound, 15 mins

Marilyn Halford, Footsteps, 1974, b/w, sound, 6 mins

PROGRAMME NOTES

SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT: 1

Tuesday 27 May 2008, at 6pm

Zurich Videoex Festival Cinema Z3

SLIDES

Annabel Nicolson, 1970, colour, silent, 11 mins (18fps)

“A continuing sequence of tactile films were made in the printer from my earlier material. 35mm slides, light leaked film, sewn film, cut up to 8mm and 16mm fragments were dragged through the contact printer, directly and intuitively controlled. The films create their own fluctuating colour and form dimensions defying the passive use of ‘film as a vehicle’. The appearance of sprocket holes, frame lines etc., is less to do with the structural concept and more of a creative, plastic response to whatever is around.” (Annabel Nicolson, LFMC catalogue 1974)

AT THE ACADEMY

Guy Sherwin, 1974, b/w, sound, 5 mins

“Makes use of found footage hand printed on a simple home-made contact printer, and processed in the kitchen sink. At The Academy uses displacement of a positive and negative sandwich of the same loop. Since the printer light spills over the optical sound track area, the picture and sound undergo identical transformations.” (Guy Sherwin, LFMC catalogue 1979)

SHEPHERD’S BUSH

Mike Leggett, 1971, b/w, sound, 15 mins

“Shepherd’s Bush was a revelation. It was both true film notion and demonstrated an ingenious association with the film-process. It is the procedure and conclusion of a piece of film logic using a brilliantly simple device; the manipulation of the light source in the Film Co-op printer such that a series of transformations are effected on a loop of film material. From the start Mike Leggett adopts a relational perspective according to which it is neither the elements or the emergent whole but the relations between the elements (transformations) that become primary through the use of logical procedure.” (Roger Hammond, LFMC catalogue supplement, 1972)

FILM NO. 1

David Crosswaite, 1971, colour, sound, 10 mins

“Film No. 1 is a 10-minute loop film. The systems of super-imposed loops are mathematically inter-related in a complex manner. The starting and cut off points for each loop are not clearly exposed, but through repetitions of sequences in different colours, in different ‘material’ realities (i.e. a negative, positive, bas-relief, neg-pos overlay) yet in constant rhythm (both visually and on the soundtrack hum) one is manipulated to attempt to work out the system structure … The film deals with permutations of material, in a prescribed manner but one by no means ‘necessary’ or logical (except within the film’s own constructed system/serial.)” (Peter Gidal, LFMC catalogue 1974)

DRESDEN DYNAMO

Lis Rhodes, 1971, colour, sound, 5 mins

“This film is the result of experiments with the application of Letraset and Letratone onto clear film. It is essentially about how graphic images create their own sound by extending into that area of film which is ‘read’ by optical sound equipment. The final print has been achieved through three separate, consecutive printings from the original material, on a contact printer. Colour was added, with filters, on the final run. The film is not a sequential piece. It does not develop crescendos. It creates the illusion of spatial depth from essentially, flat, graphic, raw material.” (Tim Bruce, LFMC catalogue 1993)

VERSAILLES I & II

Chris Garratt, 1976, b/w, sound, 11 mins

”For this film I made a contact printing box, with a printing area 16mm x 185mm which enabled the printing of 24 frames of picture plus optical sound area at one time. The first part is a composition using 7 x 1-second shots of the statues of Versailles, Palace of 1000 Beauties, with accompanying soundtrack, woven according to a pre-determined sequence. Because sound and picture were printed simultaneously, the minute inconsistencies in exposure times resulted in rhythmic fluctuations of picture density and levels of sound. Two of these shots comprise the second part of the film which is framed by abstract imagery printed across the entire width of the film surface: the visible image is also the sound image.” (Chris Garratt, LFMC catalogue 1978)

SILVER SURFER

Mike Dunford, 1972, b/w, sound, 15 mins

“A surfer, filmed and shown on tv, refilmed on 8mm, and refilmed again on 16mm. Simple loop structure preceded by four minutes of a still frame of the surfer. An image on the borders of apprehension, becoming more and more abstract. The surfer surfs, never surfs anywhere, an image suspended in the light of the projector lamp. A very quiet and undramatic film, not particularly didactic. Sound: the first four minutes consists of a fog-horn, used as the basic tone for a chord played on the organ, the rest of the film uses the sound of breakers with a two second pulse and occasional bursts of musical-like sounds.” (Mike Dunford, LFMC catalogue supplement 1972)

FOOTSTEPS

Marilyn Halford, 1974, b/w, sound, 6 mins

“Footsteps is in the manner of a game re-enacted, the game in making was between the camera and actor, the actor and cameraman, and one hundred feet of film. The film became expanded into positive and negative to change balances within it; black for perspective, then black to shadow the screen and make paradoxes with the idea of acting, and the act of seeing the screen. The music sets a mood then turns a space, remembers the positive then silences the flatness of the negative.” (Marilyn Halford, LFMC catalogue 1978)

Back to top

Date: 28 May 2008 | Season: Videoex 2008

LONDON ON AND ON

28 May–1 June 2008

Zurich Videoex Festival Cinema Z3

Over three loosely-thematic programmes, LONDON ON AND ON surveys recent film and video made by artists who either live or work in the English capital. Since the 1960s, when the formation of the Film-Makers’ Co-operative stimulated independent production, there has been an abundance of personal filmmaking in London, reflecting uniquely English characteristics and the cultural diversity of a capital city. This series, featuring works from the last decade, demonstrates how this rich history has developed into a thriving present. Though video has become the dominant medium, many artists now turn again toward film, perhaps invigorated by its proliferation in contemporary galleries and in reaction to rumours of an end to 16mm.

Date: 28 May 2008 | Season: Videoex 2008

LONDON ON AND ON I: SOCIAL VISIONS

Wednesday 28 May 2008, at 4pm

Zurich Videoex Festival Cinema Z3

Few of these films of the urban environment were shot in London, the artists have more frequently travelled farther afield, to Europe, America and Asia, to conduct their visual inquiries into architecture and society. A musical interlude, tracing the migration of composer Stefan Wolpe, provides a more interior viewpoint.

Mirza/Butler, The Space Between, 2005, 16mm, colour, silent, 12 min

Emily Richardson, Block, 2005, 16mm, colour, sound, 12 min

Redmond Entwistle, Social Visions, 2000, 16mm, b/w, sound, 15 min

Jayne Parker, Stationary Music, 2005, video, b/w, sound, 16 min

Matthew Noel Tod, Jetzt im Kino, 2003, video, colour, sound, 12 min

Lucia Nogueira, Smoke, 1996, 16mm, b/w, sound, 5 min

Guy Sherwin, Rallentando, 2000, 16mm, b/w, sound, 9 min

PROGRAMME NOTES

LONDON ON AND ON I: SOCIAL VISIONS

Wednesday 28 May 2008, at 4pm

Zurich Videoex Festival Cinema Z3

THE SPACE BETWEEN

Karen Mirza & Brad Butler, 2005, 16mm, colour, silent, 12 min

Time and space shattered into shards of light. The footage was shot in India and thoroughly reworked in the optical printer into a rigorous, flickering duality. (MW)

BLOCK

Emily Richardson, 2005, 16mm, colour, sound, 12 min

Day through night, a portrait of a 1960s London tower block, its interior and exterior spaces explored and revealed. Patterns of activity build a rhythm and viewing experience not dissimilar from the daily observations of the security guard sat watching the flickering screens with their fixed viewpoints and missing pieces of action. (ER)

SOCIAL VISIONS

Redmond Entwistle, 2000, 16mm, sound, b/w, 15 min

Social Visions suggests the myriad histories and futures that constitute Los Angeles; a city whose public image has been used as cover for the abuse of its population but also a city where one senses the potential for radical social change. The film is about the impossibility of adequately representing a city when whole sections of the population are excluded from the channels of power. (RE)

STATIONARY MUSIC

Jayne Parker, 2005, video, b/w, sound, 16 min

Poetic record of ‘Sonata 1’ (1925) by modernist Stefan Wolpe – a Jewish communist who was forced to flee Germany in 1933, ultimately making the transition from the Bauhaus to Black Mountain College. An appropriately still and empathetic camera captures this vibrant solo piano performance by his daughter Katerina, who first recounts some of the composer’s personal history. (MW)

JETZT IM KINO

Matthew Noel-Tod, 2003, video, sound, colour, 12 min

Jetzt im Kino (literally ‘Now in the Cinema’) brings together adapted texts from Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s ‘Painting, Photography, Film’, Rudolf Arnheim’s ‘Film As Art’, David Cooper’s polemical psychology book ‘The Grammar of Living’ and writings from and around Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s film The Marriage of Maria Braun into a hybrid narrative floating across the cityscape of modern Berlin. (MNT)

SMOKE

Lucia Nogueira, 1996, 16mm, b/w, sound, 5 min

A black bench looks out across the sea, and we hear the sound of kites flapping in the wind. Black pigeons fly through the air, their flight echoed by black kites. One kite is manipulated by an old man who looks like he’s performing hyperpassionate tai chi moves. The string is barely visible, and you only see the kite’s shadow, but it doesn’t matter – what’s more important is the outline of the man’s body against the sky and the graceful language he creates with his gestures. (Emily Spears Meers)

RALLETANDO

Guy Sherwin, 2000, 16mm, b/w, sound, 9 min

Accelerating and decelerating movements of a train, of film-speed, and of music derived from Honegger’s ‘Pacific 231’. (GS)

Back to top

Date: 30 May 2008 | Season: Videoex 2008

SOCIAL WORKS: NEW DOCUMENTARY FORMS

Friday 30 May 2008, at 4pm

Zurich Videoex Festival Cinema Z3

Long before the celebrated ‘Free Cinema’ movement of the 1950s, British-based filmmakers were advancing the documentary form through innovative styles and techniques. Beginning with a hilariously absurd travelogue from 1924, this programme traces that development through good times and bad, resolute with humour and irony.

Adrian Brunel, Crossing the Great Sagrada, 1924, 35mm, tinted b/w, sound, 10 min

Arthur Elton & E.H. Anstey, Housing Problems, 1935, 35mm, b/w, sound, 13 min

Stefan & Franciszka Themerson, Calling Mr Smith, 1943, 35mm, colour, sound, 10 min

Len Lye, N or NW, 1938, 35mm, b/w, sound, 8 min

Charles Ridley, Germany Calling, 1941, 16mm, b/w, sound, 2 min

Claude Goretta & Alan Tanner, Nice Time, 1957, 16mm, b/w, sound, 17 min

John Bennett, Papercity, 1969, 35mm, colour, sound, 5 minutes

PROGRAMME NOTES

SOCIAL WORKS: NEW DOCUMENTARY FORMS

Friday 30 May 2008, at 4pm

Zurich Videoex Festival Cinema Z3

CROSSING THE GREAT SAGRADA

Adrian Brunel, 1924, 35mm, tinted b/w, sound, 10 min

The film is a humorous spoof of a travelogue. Travel films were popular in the Twenties, documenting foreign cultures in a way that tended to reflect imperial, nationalist and often racist stereotypes. Brunel sends up many of the conventions of the genre familiar to audiences. (Jamie Sexton)

HOUSING PROBLEMS

Arthur Elton & Edgar Anstey, 1935, 35mm, b/w, sound, 13 min

A watershed in British documentary making. For the first time ordinary people spoke directly to the camera about their plight. The clumsy sound-recording equipment (packed into a truck parked outside the locations in Stepney) enabled the directors to achieve huge impact by filming the slum dwellers as they described life inside their wretched houses. The film was made to promote the use of gas as a clean and modern fuel by associating it with the throwing out of the old and the building of the new. (FourDocs)

CALLING MR SMITH

Stefan & Franciszka Themerson, 1943, 35mm, colour, sound, 10 min

The Themersons call on ‘Mr Smith’ to support the war effort as an anti-fascist struggle, illustrating its appeal with examples of Nazi oppression in Poland. The film is experimental in technique, using anamorphic lenses, still and moving images and vivid colour. While the spoken soundtrack employs a rhetoric heard elsewhere in wartime propaganda, the overall tone of the film is unusually urgent and authentic and in some sequences, images combine with music (Chopin, Szymanowski) to convey a real feeling of loss. (David Finch)

N or N.W.

Len Lye, 1938, 35mm, b/w, sound, 8 min

In N or N.W., Lye began to work with more conventionally ‘dramatic’ material. The film, advertising the benefits of writing letters and using the postal system, centred on a simple narrative of lovers at cross-purposes who are eventually reunited. Yet Lye used a number of unconventional edits, extreme close-ups, trick shots and superimposed animation in order to take a creative approach to such a conventional theme. (Jamie Sexton)

GERMANY CALLING

Charles Ridley, 1941, 35mm, b/w, sound, 2 min

A remarkable piece of British wartime propaganda which ridicules Nazi Germany by manipulating footage of Hitler, his party officials and troops of goose stepping soldiers. All are subjected to the optical humiliation of being made dance to the ‘The Lambeth Walk’, a song that the Nazi party branded as ‘Jewish mischief and animalistic hopping.’ (MW)

NICE TIME

Claude Goretta & Alan Tanner, 1957, 16mm, b/w, sound, 17 min

Impressions of Piccadilly Circus in 1957: hot dogs and nude magazines; dumb cinema queues; posters advertising the glories of war and the horrors of science fiction; lonely faces; searching glances; the parade of amateur and professional ‘talent’; presiding over all, the ironic statue of Eros … The observation is untouched by nostalgia, and presents a devastating picture for anyone who thinks of Piccadilly Circus in romantic terms. (Monthly Film Bulletin)

PAPERCITY

John Bennett, 1969, 35mm, colour, sound, 5 min

Papercity builds an impressionistic portrait of London through still photographs and time-lapse footage. Views of the city rarely feature in experimental films of this period, but this semi-commercial production, funded by the British Film Institute, is an evocative study of everyday sights and activities. (MW)

Back to top

Date: 31 May 2008 | Season: Videoex 2008 | Tags: Shoot Shoot Shoot

SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT: 2

Saturday 31 May 2008, at 6pm

Zurich Videoex Festival Cinema Z3

The 1960s and 1970s were a defining period for artists’ film and video in which avant-garde filmmakers challenged cinematic convention. In England, much of the innovation took place at the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative, an artist-led organisation that incorporated a distribution office, projection space and film workshop. Despite the workshop’s central role in production, not all the work derives from experimentation in printing and processing. Filmmakers also used language, landscape and the human body to create less abstract works that still explore the essential properties of the film medium.

Malcolm Le Grice, Threshold, 1972, colour, sound, 10 mins

Chris Welsby, Seven Days, 1974, colour, sound, 20 mins

Peter Gidal, Key, 1968, colour, sound, 10 mins

Stephen Dwoskin, Moment, 1968, colour, sound, 12 mins

Gill Eatherley, Deck, 1971, colour, sound, 13 mins

William Raban, Colours of this Time, 1972, colour, silent, 3 mins

John Smith, Associations, 1975, colour, sound, 7 mins

PROGRAMME NOTES

SHOOT SHOOT SHOOT: 2

Saturday 31 May 2008, at 6pm

Zurich Videoex Festival Cinema Z3

THRESHOLD

Malcolm Le Grice, 1972, colour, sound, 10 mins

“Le Grice no longer simply uses the printer as a reflexive mechanism, but utilises the possibilities of colour-shift and permutation of imagery as the film progresses from simplicity to complexity … With the film’s culmination in representational, photographic imagery, one would anticipate a culminating ‘richness’ of image; yet the insistent evidence of splice bars and the loop and repetition of the short piece of found footage and the conflicting superimposition of filtered loops all reiterate the work which is necessary to decipher that cinematic image.” (Deke Dusinberre, LFMC catalogue 1993)

SEVEN DAYS

Chris Welsby, 1974, colour, sound, 20 mins

“The location of this film is by a small stream on the northern slopes of Mount Carningly in southwest Wales. The seven days were shot consecutively and appear in that same order. Each day starts at the time of local sunrise and ends at the time of local sunset. One frame was taken every ten seconds throughout the film. The camera was mounted on an Equatorial Stand, which is a piece of equipment used by astronomers to track the stars. Rotating at the same speed as the earth, the camera is always pointing at either its own shadow or at the sun. Selection of image (sky or earth; sun or shadow) was controlled by the extent of cloud coverage. If the sun was out the camera was turned towards its own shadow; if it was in the camera was turned towards the sun.” (Chris Welsby, LFMC catalogue 1978)

KEY

Peter Gidal, 1968, colour, sound, 10 mins

“Slow zoom out and defocus of …” (Peter Gidal, LFMC catalogue 1974)

MOMENT

Stephen Dwoskin, 1968, colour, sound, 12 mins

“One single continuous shot of a girl’s face before, during and after an orgasm. A concentration on the subtle changes within the face – going from an objective look into a subjective one and then back out … Moment is not a woman alone, but with her ‘in person’. Have you ever really watched the face in orgasm?” (Stephen Dwoskin, Other Cinema catalogue 1972)

DECK

Gill Eatherley, 1971, colour, sound, 13 mins

“During a voyage by boat to Finland, the camera records three minutes of black and white 8mm film of a woman sitting on a bridge. The preoccupation of the film is with the base and with the transformation of this material, which was first refilmed on a screen where it was projected by multiple projectors at different speeds and then secondly amplified with colour filters, using positive and negative elements and superimposition on the London Co-op’s optical printer.” (Gill Eatherley, Light Cone catalogue, 1997)

COLOURS OF THIS TIME

William Raban, 1972, colour, silent, 3 mins

“Whilst working on previous time-lapse films, I found that colour film tended to record the actual colour of the light source rather than local colour when long time exposures were used. Using this phenomenon, Colours of this Time records all the imperceptible shifts of colour temperature in summer daylight, from first light until sunset.” (William Raban, LFMC catalogue 1974)

ASSOCIATIONS

John Smith, 1975, colour, sound, 7 mins

“Text taken from ‘Word Associations and Linguistic Theory’ by Herbert H. Clark. Images taken from magazines and colour supplements. By using the ambiguities inherent in the English language, Associations sets language against itself. Image and word work together/against each other to destroy/create meaning.” (John Smith, LFMC catalogue 1978)

Back to top

Date: 1 June 2008 | Season: Videoex 2008

LONDON ON AND ON II: SURFACE STRUCTURES

Sunday 1 June 2008, at 4pm

Zurich Videoex Festival Cinema Z3

Exploring the surface of the film strip, the surface of the earth and the structures that make up cinematic movement, the programme begins with an overwhelming barrage and ends with a sliver of carpaccio. Between those extremes, time-lapse films survey the landscape or atmosphere and John Smith directs the flow of traffic.

Greg Pope, Shadow Trap, 2007, 35mm cinemascope, colour, sound, 8 min

Nicky Hamlyn, Water Water, 2005, 16mm, b/w & colour, silent, 11 min

William Raban, Continental Drift, 2005, 35mm, colour, sound, 15 min

John Smith, Worst Case Scenario, 2003, video, b/w & colour, sound, 18 min

Alix Poscharsky, As We All Know, 2006, 16mm cinemascope, colour, silent, 8 min

Emma Hart, Skin Film 3, 2006, 16mm, colour, sound, 11 min

PROGRAMME NOTES

LONDON ON AND ON II: SURFACE STRUCTURES

Sunday 1 June 2008, at 4pm

Zurich Videoex Festival Cinema Z3

SHADOW TRAP

Greg Pope, 2007, 35mm cinemascope, colour, sound, 8 min

Shards of emulsion produced during the auto-destructive film performance Light Trap have been layered and structured onto clear 35mm. Extending across the soundtrack area, the synaesthetic image creates an intense volley of sound and light. (MW)

WATER WATER

Nicky Hamlyn, 2005, 16mm, b/w & colour, silent, 11 min

Water Water is based around a set of antinomies that operate at various levels, from between frames to between the two halves of the film. The first is composed of individually filmed frames (animation) which form shots of interlaced contrary motion. In the second half, dissolves replace cuts, light softens and contrast decreases. (NH)

CONTINENTAL DRIFT

William Raban, 2005, 35mm, colour, sound, 15 min

A land and sea-scape film drawn from rich sources of imagery: the constantly changing mood of the sea to the distinctly different shorelines of Kent and the Pas de Calais – 21 miles of water that define both the ‘island race’ and hostility towards a wider integration within Europe. (WR)

WORST CASE SCENARIO

John Smith, 2003, video, b/w & colour, sound, 18 min

Worst Case Scenario looks down onto a busy Viennese intersection and a corner bakery. Constructed from hundreds of still images, it presents situations in a stilted motion, often with sinister undertones. Through this technique we’re made aware of our intrinsic capacity for creating continuity, and fragments of narrative, from potentially (no doubt actually) unconnected events. (MW)

AS WE ALL KNOW

Alix Poscharsky, As We All Know, 2006, 16mm cinemascope, colour, silent, 8 min

Referencing science fiction, this film is about the discrepancy between scientific world view and everyday life. We know the earth is moving round the sun, but viewed from earth the sun appears to be moving round the earth. This film poses the question whether knowing (or ‘seeing’) is not just another form of believing, as, ultimately, what is shown in the film, is merely earth’s rotations around its own axis. (AP)

SKIN FILM 3

Emma Hart, 2003/06, 16mm, colour, sound, 11 min

By sticking Sellotape to my skin and then peeling it off, I took off the top surface of my skin. I then stuck the tape and the skin to clear 16mm film. It is my actual skin that goes through the projector. It is a film of my total surface area. From head to toe. (EH)

Back to top

Date: 1 June 2008 | Season: Videoex 2008

LONDON ON AND ON III: A PLACE TO BE

Sunday 1 June 2008, at 6pm

Zurich Videoex Festival Cinema Z3

The most personal of the three contemporary programmes considers our situation in relation to others and our surroundings, with poetic works that look in at the viewer, and out into the world. Featuring characters alienated by circumstance or isolated by choice, it ends with a wistful song of love.

Dalia Neis, Saints, 2005, 16mm, b/w, silent, 5 min

Miranda Pennell, You Made Me Love You, 2005, video, colour, sound, 4 min

Jimmy Robert, L’Éducation sentimentale, 2005, 35mm, b/w & colour, silent, 5 min

Ben Rivers, This is My Land, 2006, 16mm, b/w, sound, 14 min

Alia Syed, Eating Grass, 2003, 16mm, colour, sound, 23 min

Emily Wardill, Ben, 2007, 16mm, colour, sound, 10 min

Oliver Harrison, Love is All, 1999, 35mm, colour, sound, 4 min

PROGRAMME NOTES

LONDON ON AND ON III: A PLACE TO BE

Sunday 1 June 2008, at 6pm

Zurich Videoex Festival Cinema Z3

SAINTS

Dalia Neis, Saints, 2005, 16mm, b/w, silent, 5 min

A reflection on cinema and its relationship to devotional belief. Saints presents itself as a fragment from an abandoned folk archive; a document of portraits of North African, Jewish and Islamic saints. It is believed that through meeting the gaze of a saint, their wisdom and courage are transmitted to the onlooker. (DN)

YOU MADE ME LOVE YOU

Miranda Pennell, 2005, video, colour, sound, 4 min

A group of teenage performers are filmed as a sea of faces, filling the frame, locked onto and following the single take, studio set, stop-start journey of the camera like a shoal of attentive fish. The piece’s minimalist movement vocabulary of walking, stopping, turning and swaying is suggested mainly by the sound of moving feet and sudden silences as the striving to maintain an unbroken relationship of performer gaze to camera/viewer becomes the central focus of the work. (Chirstinn Whyte)

L’ÉDUCATION SENTIMENTALE

Jimmy Robert, 2005, 35mm, b/w & colour, silent, 5 min

Bas Jan Ader disappeared at sea over 30 years ago. My new film acts as an intervention on his filmed performances. In five minutes I attempt to locate myself within his vocabulary, re-enacting gestures that I identify with, whether these gestures come from record covers, such as David Bowie’s ‘Heroes’ or ‘The Idiot’ by Iggy Pop or appropriations and transformations of Bas Jan Ader’s own work. (JR)

THIS IS MY LAND

Ben Rivers, 2006, 16mm, b/w, sound, 14 min

A portrait of Jake Williams, who lives alone within miles of forest in Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Jake always has many jobs on at any one time, rarely throws anything away, is an expert mandolin player, and has compost heaps going back many years. It struck me straight away that there were parallels between our ways of working – I have tried to be as self-reliant as possible and be apart from the idea of industry – Jake’s life and garden are much the same – he can sustain himself from what he grows and so needs little from others. (BR)

EATING GRASS

Alia Syed, 2003, 16mm, colour, sound, 23 min

Shot in London, Karachi and Lahore and encompassing five stories relating to the times of day for Muslim prayer, this visually stunning work explores overlaps between time, memory and location through Syed’s use of allegory and complex editing. By building tonal rhythmical cadences – similar musical structures to those found in jazz or Indian classical music – meaning is not only conveyed by what is said, but also by repeated rhythms built up as the textures of individual voices slip from one language to another. Meanwhile the shadows cast by the sun become emotional triggers for a young woman whose present is continually enmeshed with the past. (inIVA)

BEN

Emily Wardill, 2007, 16mm, colour, sound, 10 min

Shot in colour on a set that was built in black and white, Ben re-inhabits a famous case study involving hypnosis. The authority of the case study, the rickety construction of the set, and the faltering voice over hold the film together in a precarious balance. (EW)

LOVE IS ALL

Oliver Harrison, 1999, 35mm, sound, colour, 4 min

Winter bound, a snow queen dreams of love and the blooming of spring. Through frosted rococo cartouches she sings about the virtues of true love accompanied by miniature animated sequences. Originally recorded by Deanna Durbin in 1940, the lyrics are reinterpreted to portray universal ideas of love: good overcoming evil, warmth melting the snow, spring following winter. (OH)

Back to top

Date: 13 June 2008 | Season: Tony Conrad | Tags: Tony Conrad

TONY CONRAD

13—15 June 2008

London Tate Modern

Tony Conrad is a pivotal figure in contemporary culture. His multi-faceted contributions since the 1960s have influenced and redefined music, filmmaking, minimalism, performance, video and conceptual art. Known for his groundbreaking film The Flicker, his involvement in the Theatre of Eternal Music and the evolution of the Velvet Underground, and collaborations with a host of luminaries including Jack Smith, John Cale, Mike Kelley and Henry Flynt, Conrad remains a radical figure who challenges our understanding of art history. This special weekend at Tate Modern will feature a major new performance for the Turbine Hall and screenings of Conrad’s extraordinary film and video work.

Curated by Stuart Comer, Alice Koegel and Mark Webber. Assistant Curator Vanessa Desclaux.

With thanks to Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Cologne; Ed Carter, Lumen/Evolution; Tracey Ferguson; Florian Härle; Tony Herrington, The Wire; Branden W. Joseph; Christophe Kniel and Ilja Mess; Neil Lagden; Elliot Landy; David Leister; Marie Losier; Eric Namour, [no.signal]; Jay Sanders, Greene Naftali Gallery, New York; Chloë Stewart; Ann Twiselton, MIT Press; Steve Wald; Richard Whitelaw, Sonic Arts Network.

INTRODUCTION

TONY CONRAD

Friday 13 – Sunday 15 June 2008

London Tate Modern

Tony Conrad is a pivotal, polymath figure in contemporary culture, a pioneering composer, musician, performer and filmmaker, whose work emerged at the heart of New York’s fervent avant-garde art community in the early 1960s. Best known for his influential early musical explorations and the ‘experiential excess’ of his groundbreaking ‘structural film’, The Flicker, Conrad’s work offers a complex reassessment of duration and temporality, and a direct implication of the viewer as an active participant in his work. His hybrid, often perceptually intense practice has persistently expanded disciplinary boundaries and challenged traditional notions of authorship and authority for more than forty years.

After studying mathematics at Harvard, during the early 1960s Conrad developed a distinct approach to sound in contemporary musical production, introducing sustained drones built upon a strategy of minimal reduction and temporal expansion. From 1962 he was a key member of the groundbreaking Theatre of Eternal Music (also known as The Dream Syndicate). The group developed ‘Dream Music’ which dispensed with written scores and critiqued the history of western orchestral performance. Utilising long durations, precise pitch and blistering volume, its members – including Conrad, La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela and future Velvet Underground co-founders John Cale and Angus MacLise – forged a performance collaboration which denied the activity of composition, examined the physical elements of sound, and established a principal branch of the minimalist tradition. Following the dissolution of the group in 1965, Conrad has continued to reflect on duration as a concept in various fields conventionally distinguished as music, film, performance and the visual arts, always challenging his audience in whatever medium he employs.

Throughout his career Conrad has sought ‘physiological and psychological phenomena’ that produce a profound interaction with the audience. The stroboscopic, psychedelic intensity of films like The Flicker and the saturated energy and long duration of Conrad’s music can become powerful, moving and unsettling experiences that heighten awareness both of the physical experience of the event and of one’s own subjectivity within it. Carrying over from one medium to another, Conrad sets up situations that encourage free experiences of audiovisual perception and perceptual engagement, ‘manufacturing the culture as the event proceeds, as the context sustains.’

Much of Conrad’s work has involved collaboration, from the Theatre of Eternal Music to his involvement with the philosopher, musician and anti-art activist Henry Flynt, his early creative partnership with the underground artist and filmmaker Jack Smith, his participation in the influential Department of Media Study at the State University of New York at Buffalo, and more recent projects with artists such as Mike Kelley and Tony Oursler. As his career has shifted and intersected with these diverse artists, agendas and positions, Conrad has problematised not only his own work but the conventional set of categories used to contain and define it. A reconsideration of his practice also problematises traditional linear histories of the movements and developments with which he has been associated: minimalism, Fluxus, early conceptualism, underground and structural film, paracinema or expanded cinema, performance and video. The heterogeneous nature of Conrad’s work comprises a radical and productive inconsistency that continues to subvert the power structures that regulate the writing of history.

Conrad’s approach to cinema reflects his penchant for transcending boundaries and reconfiguring conventional notions of production. The Flicker, his rallying call for a new age of cinema, led the philosopher Gilles Deleuze to muse on a ‘cinema of expansion without camera, and also without screen or film stock,’ a cinema in which ‘anything can be used as a screen, the body of a protagonist or even the bodies of the spectators; anything can replace the film stock, in a virtual film which now only goes on in the head, behind the pupils.’ Conrad’s films do not rely only on luminous, audiovisual stimulation and extreme perceptual states. He has also explored a wide range of unusual materials and production methods, experimenting with various ways of cooking film – treating raw film stock as an ingredient to be stir-fried or pickled, and then projected. He has also played film as a musical instrument, stretched taut and played upon with a bow, and has used a Tesla coil to electrocute film stock.

This theatrical, performative approach to creating films makes process and production an integral and evident part of the work. The relationships between process, projection and performance have a long history within Conrad’s work and take on particular resonance in Early Minimalism, a series of compositions which refer to and redress the artist’s history with the Theatre of Eternal Music. Performances take place behind a scrim, backlit to create shadows of the performers, a spectral doubling to complicate the work’s relationship to the past.

Unprojectable: Projection and Perspective, a new commission in which Conrad addresses the immense space of Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall with its central bridge as a stage, exposes us to his most recent exploration of projection and long duration on a major scale. A tremendous sound will fill the Turbine Hall, starting off with a buzzing pulse at 25 per second, mixed with an amplified string quartet including Conrad on violin, an electric drill and hand-held phonograph arms. Billowing scrims on either side of the bridge function as projection screens for the performative activities enacted behind them. These actions will include the live music performance and re-enactments of alternative film production processes Conrad developed in the mid-1970s, such as drilling holes in raw film stock. While the audience occupies the floor below, Conrad’s back-projected, larger-than-life silhouette will loom large, swaying in response to the production of sounds which will generate a pressure-filled auditory environment. The intensity of the sound will ground the event in the physical and perceptual space of the present, while the shadows might be read as a comment on the status of the present versus the re-presented and non-recoverable past in the archive of musical and visual culture.

—Stuart Comer, Tate Modern, Curator: Film

—Alice Koegel, Tate Modern, Curator: Contemporary Art and Performance

Back to top

Date: 13 June 2008 | Season: Tony Conrad | Tags: Tony Conrad

TONY CONRAD: FLICKER AND PROCESS FILMS

Friday 13 June 2008, at 7pm

London Tate Modern

Minimal cinema with maximal effect. Few films provide the intense, stroboscopic viewing experience of The Flicker, a non-objective film composed only of opaque and clear frames, and a pulsing electronic soundtrack. Conrad’s cinematic debut still astounds audiences four decades after its creation, and will be screened together with other works exploring audio-visual harmonics and the radical production processes of cooked and electrocuted films.

The screening, introduced by Tony Conrad, will be followed by a reception to celebrate the publication of “Beyond the Dream Syndicate” (Zone Books/MIT).

Tony Conrad, The Flicker, 1966, 30 min

Tony Conrad, Curried 7302, 1973, 2 min

Tony Conrad, 7302 Creole, 1973, 1 min

Tony Conrad, 4-X Attack, 1973, 2 min

Tony Conrad, Film Feedback, 1974, 14 min

Tony Conrad, Articulation of Boolean Algebra for Film Opticals, 1975, 10 min excerpt

Tony Conrad, The Eye of Count Flickerstein, 1967/75, 7 min

Beverly & Tony Conrad, Straight and Narrow, 1970, 10 min

PROGRAMME NOTES

TONY CONRAD: FLICKER AND PROCESS FILMS

Friday 13 June 2008, at 7pm

London Tate Modern

THE FLICKER

Tony Conrad, USA, 1966, 16mm, b/w, sound, 30 min

I think that The Flicker acts as a very versatile art object. The observer can really use it to his own means over a wide range of possibilities. The beauty lies within the beholder himself. In most aesthetic presentations – drama, cinema, music – the common attitude is that the amusement or the beauty or the effect of the experience is wholly within the entertainer; that the entertainer is actually creating the impressions or the reaction himself. The Flicker, I think, presents a clean-cut case of the experience lying within the observer. Most of the details, most of the impact, most of what people find it in, what they take away from having watched the film, wasn’t there, was conjured up only when they watched this film: it didn’t exist before, it doesn’t exist on film, it wasn’t on the screen.

CURRIED 7302

Tony Conrad, USA, 1973, 16mm, colour, silent, 2 min

Conrad began a series of ‘Cooked Films’ in 1973. Folding social and political concerns into the process in an explicit manner, Conrad – who at the time was serving as primary caregiver to his child, as well as professor of film at Antioch – adapted the practice of filmmaking to the stereotypically female role of domestic cook. Usually substituting ‘raw’ film in the place where different recipes called for onions, Conrad ‘processed’ the footage in various manners on his countertop or stove, with the result being, as Conrad recalled about Curried 7302 (1973), “this gorgeous mottled yellow, abstract thing.” (Branden Joseph

7302 CREOLE

Tony Conrad, USA, 1973, 16mm, colour, silent, 1 min

The second work in the series was a film chicken creole, the projection of which caused – through the thick alimentary residue still clinging to the celluloid – gate slipping and other effects simulated in structural films. “Well, this was very interesting because the meat ran all over the projector, and it was full of grease and chicken. It slipped in the gate, and it stunk because the lamp heated it up, and it was really like an olfactory experience, and it tested the skill of the projectionist, who is covered in slime …” (Branden Joseph

4-X ATTACK

Tony Conrad, USA, 1973, 16mm, b/w, silent, 2 min

Foregrounding the manner in which film could be ‘exposed’ and developed via heat, pressure, or electricity, rather than merely by light and developer fluid, Conrad produced a ‘material’ paracinema. In 4-X Attack, he struck a roll of celluloid with a hammer in a darkroom. “The material being brittle,” Conrad noted, “it was not only left with stress-bearing deformations, but was compressed in points, scraped and sheared in others, and generally speaking completely totalled.” Once the film was fractured into myriad pieces, Conrad swept them back together, “flashed the film once with a strobe, so as to activate the latent stress record,” developed it in a cheese cloth sack, and then painstakingly, even archeologically, reconstructed the roll (it is, afterall, an ‘edited’ film) into a projectable movie.” (Branden Joseph

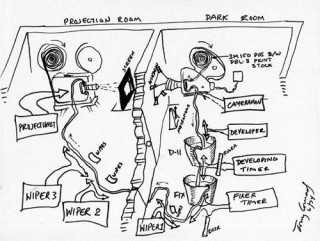

FILM FEEDBACK

Tony Conrad, USA, 1974, 16mm, b/w, silent, 14 min

The cybernetics of video applied to film production. Film Feedback was produced in ‘real time’ by processing and projecting the film while it was being shot. Made with a film-feedback team which I directed at Antioch College. Negative image is shot from a small rear-projection screen, the film comes out of the camera continuously (in the dark room) and is immediately processed, dried, and projected on the screen by the team. What are the qualities of film that may be made visible through feedback?

ARTICULATION OF BOOLEAN ALGEBRA FOR FILM OPTICALS

Tony Conrad, USA, 1975, 16mm, b/w, sound, 75 min (10 min excerpt)

The work that served for me as a checkmate in the ‘structural’ film game is Articulation of Boolean Algebra for Film Opticals. This film achieved something of an apogee in formalist design, that conceptual regimentation which, in relation to de Sade’s eroticism, Barthes called “encyclopaedic […] the same inventorial spirit which animates Newton or Fourier.” (The Metaphor of the Eye, 1963.) Articulation literally unifies the optical and sound tracks. Both are the result of a design that follows an algorithmic system of stripes. The scale of the six stripes on the film strip positions them in relation to screen design, flicker, tone, rhythm, and meter, all with octave relationships.

THE EYE OF COUNT FLICKERSTEIN

Tony Conrad, USA, 1967/75, 16mm, b/w, silent, 7 min

The sustained dead gaze of black and white TV ‘snow’, captured in 1965 and twisted sideways, draws the viewer hypnotically into an abstract visual jungle.

STRAIGHT AND NARROW

Beverly & Tony Conrad, USA, 1970, 16mm, b/w, sound, 10 min

Straight and Narrow is a study of subjective colour and visual rhythm. Although it is printed on black and white film, the hypnotic pacing of the images will cause most viewers to experience a programmed gamut of hallucinatory colour effects. Through the intermediary of rhythm, the maximal impact is drawn from the simplest of universal human images: straight horizontal and vertical lines.

All texts or quotes by Tony Conrad unless otherwise noted. Texts by Branden Joseph have been adapted from “Beyond the Dream Syndicate: Tony Conrad and the Arts After Cage” (Zone Books / MIT Press).

Back to top