Date: 8 October 2000 | Season: Leeds Film Festival 2000

BRITISH AVANT-GARDE: AN INTRODUCTION TO THE LONDON FILM-MAKERS’ COOPERATIVE

Sunday 8 October 2000, at 5:30pm

Leeds City Art Gallery

In 1966, influenced by the apparent success of the Film-Makers’ Cooperative run by Jonas Mekas in New York, a group of English film devotees came together to form the London Filmmakers’ Coop. At this time, the London art film scene centred on the liberal Better Books store, managed by concrete poet Bob Cobbing. In the basement of the shop, Cobbing mounted exhibitions, happenings and held screenings of early American avant-garde films by Maya Deren, Kenneth Anger, Stan Brakhage and others. Nearby, the UFO and Middle Earth night-clubs also showed underground films to accompany all-night concerts by psychedelic rock groups like The Pink Floyd and Soft Machine.

At first, the London Coop was populated more by viewers than filmmakers, and the distribution collection comprised mainly of films from the USA, which had remained in London after the critic P. Adams Sitney had completed his New American Cinema tour of Europe. Only a few maverick characters such as Jeff Keen and Anthony Balch had made original works free of the conventional BFI Production Board. Following the Coop’s relocation to the Arts Laboratory, which resulted in changes in leading personal, new members of the group began to actively produce films as printing and processing facilities were provided in-house for their use. From this time on, the more anarchic, carefree approach embodied in the films of Steve Dwoskin (an American ex-pat with links to Andy Warhol’s Factory and who’s films featured the New York underground stars), gave way to a more formal style led by fellow countryman Peter Gidal, and former painter Malcolm Le Grice, who both exerted an enormous influence through their innovative work and tireless activities. Exerting his influence on the next wave of filmmakers through screenings, writings and teaching, Le Grice became the leading light of the English avant-garde.

By the early 1970s, hundreds of films were being produced in a variety of personal styles. Access to the coop’s home-made equipment led to much investigation of the film material, as seen in the early films of Guy Sherwin and Lis Rhodes, which directly use the printing process to give the film its form and content. Many English filmmakers, including Mike Dunford and Annabel Nicolson, analysed the possibilities of re-filming projected images, in a similar manner to Ken Jacobs’ Tom, Tom the Piper’s Son (screening on October 14th). Dwoskin used this technique in Dirty, to reinterpret some of his early erotic footage. Le Grice, Gidal, Du Cane and Crosswaite were more in line with the purist Structural film movement, while Breakwell’s Repertory and the films of John Smith (see separate programme), used humour to disguise formal concerns.

After collaborating on the two-screen film River Yar (1972), Chris Welsby and William Raban led a tradition of British landscape film, often using time-lapse photography to portray the environment. Jeff Keen and John Latham were renegades, independent of the Coop community, creating singular works mixing live action and animation. Many of the filmmakers represented in this programme ventured beyond the accepted boundaries of filming to make multi-screen or expanded cinema events.

The LFMC continued to struggle with problems of funding and location until being re-housed in the purpose built facility in 1998. In this more clinical and businesslike environment, the Coop unfortunately lost much of its character and community spirit. Financial problems in recent years led to a merger with London Electronic Arts, a similar organisation representing artists’ video. The Lux Centre for Film, Video and Digital Arts now comprises of a unique cinema, video art gallery and an unparalleled distribution outlet.

Ian Breakwell, Repertory, UK, 1973, 9 min

Guy Sherwin, At The Academy, UK, 1974, 5 min

John Du Cane, Relative Duration, UK, 1973, 10 min

Malcolm Le Grice, Threshold, UK, 1972, 10 min

Peter Gidal, Hall, UK, 1968-69, 10 min

David Crosswaite, The Man With The Movie Camera, UK, 1973, 8 min

William Raban, Angles Of Incidence, UK, 1973, 12 min

Chris Welsby, Park Film, UK, 1972, 7 min

Lis Rhodes, Dresden Dynamo, UK, 1974, 5 min

Stephen Dwoskin, Dirty, UK, 1965-67, 10 min

Jeff Keen, Marvo Movie, UK, 1967, 5 min

John Latham, Speak, UK, 1968-69, 11 min

The programme will be introduced by curator Mark Webber.

Back to top

Date: 8 October 2000 | Season: Leeds Film Festival 2000

BRITISH AVANT-GARDE: WORDS AND PICTURES BY JOHN SMITH

Sunday 8 October 2000, at 9pm

Leeds City Art Gallery

The films of John Smith conduct a serious investigation into the combination of sound and image, but unlike many more po-faced formal filmmakers, Smith does so with a sense of humour that reaches out beyond the traditional avant-garde audience. His films move between narrative and absurdity, constantly undermining the traditional relationship between the visual and aural. By blurring the perceived boundaries of experimental film, fiction and documentary, Smith never deliveries what he has led the spectator to expect. In very short films such as Om (1986) and Gargantuan (1992), Smith slowly reveals that nothing is quite as it seems.

Associations (1975) interprets a reading from “Word Associations and Linguistic Theory” by offering a cinematic game of rebus, in which words are replaced by pictures taken from magazines. The heavy academic spoken text is mocked by a series of ridiculous visual puns. In The Girl Chewing Gum (1976), an authoritative voice-over appears to direct the everyday events taking place on a street corner in Hackney. As the film develops, the narrator skilfully impairs our understanding, creating ambiguity from that which appears straightforward.

Smith’s work often focuses on an obsession with mundane details, a technique best displayed in The Black Tower (1987), in which a vision of a tower on every horizon leads to a subtle descent into madness. His award winning film Blight, a collaboration with composer Jocelyn Pook, creates a fictional reality while documenting the demolition of houses to make way for the controversial M11 link road.

John Smith, Om, UK, 1986, 4 min

John Smith, Association, UK, 1975, 7 min

John Smith, Leading Light, UK, 1975, 11 min

John Smith, The Girl Chewing Gum, UK, 1976, 12 min

John Smith, The Black Tower, UK, 1985-87, 24 min

John Smith, Gargantuan, UK, 1992, 1 min

John Smith, Blight, UK, 1994-96, 14 min

John Smith, The Waste Land, UK, 1999, 5 min

John Smith & Ian Bourn, The Kiss, UK, 1999, 5 min

John Smith will be present to introduce and discuss his films. Two videotapes of his work are available from the Lux Centre in London.

Back to top

Date: 10 October 2000 | Season: Leeds Film Festival 2000, Little Stabs at Happiness

LITTLE STABS AT HAPPINESS

Tuesday 10 October 2000, at 8:30pm

Leeds The Hi-Fi

“Why do they do it Montag ? It’s sheer perversion”.

“Little Stabs At Happiness”, a nightclub hosted by Mark Webber of the pop group Pulp, has been taking place at the ICA in London since December 1997. The club, named after a Ken Jacobs short, presents films and music seldom seen or heard in public. Early in the evening there will be screenings of three short underground films by Manuel De Landa, Charles Levine and Owen Land, interspersed with experimental music or middle-of-the-road classics played at a low volume so you can sit around and talk. The music stops to make way for Francois Truffaut’s oddball feature Fahrenheit 451, a glimpse of a future where books are burned and big brother is always watching. When the credits roll, the volume rises and the dancing begins. DJ’s Gregory Kurcewicz, BR Wallers and Mark Webber play real songs with a beat you dance to. Reacquaint yourself with records you’d forgot as we roll out the disco classic, new wave big beats and chart toppers of yesteryear. This ain’t no arty poseur nonsense or kitsch school disco trip down memory lane.

Fahrenheit 451 (François Truffaut, 1966)

Plus: Wide Angle Saxon (Owen Land, 1974); Peaches and Cream (Charles Levine, 1969); The Itch-Scratch-Itch Cycle (Manuel De Landa, 1977)

Date: 13 October 2000 | Season: Ken Jacobs Nervous System, Leeds Film Festival 2000

THE FILMS OF KEN JACOBS

Touring Film Retrospecive Introductory Essay

Ken Jacobs has been a leading innovator of avant-garde film for the past 40 years. After making his first films in the mid-1950s, Jacobs soon found himself at the forefront of the experimental film movement, which exploded in New York and across the world throughout the next decade, liberating cinema from its previous conventions. His films were developed out of despair and desperation, as an attempt to make an urban guerrilla cinema in reaction to his disappointment with the “wall to wall colour stupidity” of 1950s America. “I was interested in immediacy, a sense of ease, and an art where suffering was acknowledged but not trivialised with dramatics”.

Jacobs grew up in Brooklyn, and later spent time working in the Coast Guard in Alaska. On his return to New York, he shot Orchard Street (1956), a documentary about the Lower East Side. He studied painting under Hans Hofmann, then embarked on a series of films with Jack Smith as his leading actor, working together on a 3 hour epic titled Star Spangled To Death (1957-60). This film, which is concerned with the aesthetic of failure and collapse of order, incorporates new material with found footage.

Using the pseudonym K.M. Rosenthal (“to protect my obscurity”), he completed the influential Little Stabs At Happiness (1958-60), a series of whimsical 100-foot rolls presented as they came out of the camera. In summer 1961, Jacobs and Smith spent time in Provincetown performing The Human Wreckage Review, which preceded many of the artists’ happenings of later that decade and was prematurely closed down by the police.

“Overwhelmed, hopeless, it was a good time for irreverence. And, for an art film in the vernacular, like an amusing letter, me to you. Sketchy, airy, anti-precious, without a lot of geniusing at the audience. Not anti-art, which the critics of the period, assumed. To my bafflement.”

The Whirled (1956-61), the earliest film presented in this retrospective, features Smith in series of vignettes from the period which also yielded Little Stabs At Happiness and Blonde Cobra (1959-63), two films considered revolutionary for the way they display an entire new cinematic sensibility. Blonde Cobra was particularly radical, containing long scenes of black leader and a soundtrack that incorporates live radio, making no two projections the same. Amused with the ‘Baudelairean Cinema’ label that was bestowed upon these films by Jonas Mekas, Jacobs embarked upon a loose trilogy of longer works – Baud’lairian Capers (1963-64), The Winter Footage (1964) and The Sky Socialist (1964-65), filming with friends and new wife Florence. Three shorter films shot in their loft, Window (1964), Airshaft (1967) and Soft Rain (1968) showed Jacobs’ accomplished talent for investigating space, a refined approach rooted in his schooling by abstract expressionist Hans Hofmann. With these unique and precisely composed films, he anticipated the Structural movement, which subsequently became the dominant style of the avant-garde throughout the 1970s, being particularly prevalent among the new English filmmakers.

“The zoom lens rips, pulling depth planes apart and slapping them together, contracting and expanding in concurrence with handheld camera movements to impart a terrific apparent-motion to the complex of the object-forms pictured on screen, its horizontal-vertical axis steadied by the audience’s sense of gravity.” (from notes on Window)

Nissan Ariana Window (1969) is a more personal work, in which Jacobs turned his camera on home life to document his impressions on Flo’s pregnancy, their new daughter, and a new litter of kittens born to the family cat.

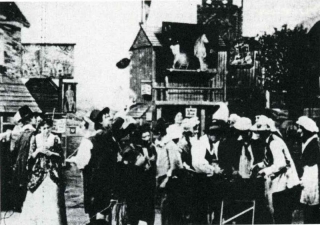

Jacobs most celebrated film is Tom, Tom The Piper’s Son (1969-71), a 2 hour tour-de-force constructed by re-photographing and dissecting a 10 minute short made by Billy Bitzer in 1905. After presenting the complete original, Jacobs pursues a deep analysis into its visual elements: slowing down, freezing action and examining small, abstracted areas of the frame.

“I wanted to ‘bring to the surface’ that multi-rhythmic collision-contesting of dark and light two-dimensional force-areas struggling edge to edge for identity of shape … to get into the amoebic grain pattern itself – a chemical dispersion pattern unique to each frame, each cold still … stirred to life by a successive 16-24fps pattering on our retinas, the teeming energies elicited (the grains! the grains!) then collaborating, unknowingly and ironically, to form the always-poignant-because-always-past illusion.”

In the same year, Jacobs began to investigate the Pulfrich pendulum effect, by which moving images are given a strong 3D depth. Seen through an ‘Eye Opener’ filter, a normally projected tracking shot of a snowbound suburban housing estate in Globe (previously titled Excerpt From The Russian Revolution, 1969) becomes an immense vista of shifting planes. (“The found sound is X-ratable but necessary to the film’s perfect balance (Globe is symmetrical) of divine and profane.”) The later film Opening The Nineteenth Century: 1896 (1990) re-presents vintage Lumiere footage with a similar strong visual effect.

The innovations of these works, together with experiences directing live action shadow plays, led to the Nervous System, a live projection technique integrating 2 analytic projectors to derive 3D and a variety of other optical effects from standard 2D footage. Each projector contains identical strips of film, usually shown 1 or 2 frames out of sync with each other. Since 1975, Jacobs has developed numerous works that often use ancient archival footage to produce uncanny illusions of depth and movement. On screen, an image can be given the appearance of constant movement without ever seeming to go anywhere. Expanding on Muybridge and Marey, Jacobs unlocks unknown possibilities hidden deep within cinema, usually lost in the unretarded flurry of frames.

In parallel to the development of the Nervous System, Jacobs continued to investigate other ways of recycling images, calling for “a Museum of Found Footage, a shit-museum of telling discards accessible to all talented viewers/auditors. A wilderness haven salvaged from Entertainment”. His Urban Peasants (1975) marries pre-war and war time home movie footage shot by his wife’s Aunt Stella with a recording of How To Speak Yiddish. In 1978, Jacobs and his students sequentially re-edited The Doctor’s Dream, a bland 1950s television drama, to expose an unexpected sexual subtext lurking between gaps in the narrative. Perfect Film (1986) presents rushes from TV news footage following the assassination of Malcolm X. The film’s structure sits comfortably alongside his other work, though surprisingly the filmmaker claims to have found the reel in a rubbish bin and considered it ‘perfect’ in its untouched state.

“I wish more stuff was available in its raw state, as primary source material for anyone to consider, and to leave for others in just that way, the evidence uncontaminated by compulsive proprietary misapplied artistry, ‘editing’, the purposeful ‘pointing things out’ that cuts a road straight through the cine-jungle; we barrel through thinking we’re going somewhere and miss it all.”

Jacobs’ version of [Buster] Keaton’s Cops, (1991) is offered via a radical intervention of the original frame. His latest films Disorient Express and Georgetown Loop (both 1996) use wide-screen 35mm (by mirror printing standard 16mm) to create abstracted Rorschach images of archival train journeys.

(Mark Webber, 2000)

Back to top

Date: 13 October 2000 | Season: Ken Jacobs Nervous System, Leeds Film Festival 2000

KEN JACOBS RETROSPECTIVE: PROGRAMME 1

Leeds International Film Festival

Friday 13 October 2000, at 6:30pm

INSTRUCTIONS TO AUDIENCE

In order to experience the added depth of the Pulfrich 3D effect, the viewer should use the “Eye Opener” filter during GLOBE. “Flat image blossoms into 3D only when viewer places EYE OPENER © 1987 before right eye. (Keeping both eyes open, of course. As with all stereo experiences, centre seats are bet. Space will deepen as one views further from the screen.)”

PLEASE RETURN YOUR FILTER TO CINEMA STAFF AFTER THE SCREENING

WINDOW

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1964, 16mm, 18fps, colour, silent, 12 min

The moving camera shapes the screen image with great purposefulness, using the frame of a window as fulcrum upon which to wheel about the exterior scene. The zoom lens rips, pulling depth planes apart and slapping them together, contracting and expanding in concurrence with camera movements to impart a terrific apparent-motion to the complex of object-forms pictured on the horizontal-vertical screen, its axis steadied by the audience,s sense of gravity. The camera’s movements in being transferred to objects tend also to be greatly magnified (instead of the camera, the adjacent building turns). About four years of studying the window preceded the afternoon of actual shooting (a true instance of cinematic action-painting). The film is as it came out of the camera, excepting one mechanically necessary mid-reel splice.

(Ken Jacobs, statement in New York Film-Makers’ Cooperative Catalog #5, 1971)

“The careful relationships of planes, textures, and lighting would not lead one to expect such a spontaneous method were it not for the marvellously fluid, active “choreography for camera”. Jacobs continually manipulates focal distance, lighting, and lenses to endow one static space with hundreds of new aspects and directions and speeds of motion.

“Major contrasts, imperceptible in the flow of a continuous viewing, can be seen on closer scrutiny of the film on an analytic projector: contrasts between flat, screen-surface planes and a deeper, textured, more recognisable geography; between geometrically shaped areas of solid black and white and grainier, coloured, reflecting or textured surfaces; between objects which occupy space, such as a water-beaded horizontal sheet of tar paper, a man and woman, a hanging globe, and a statuette and again more abstract, graphic spaces from which shapes often seem cut out; between spaces on a firm, horizontal / vertical axis and those which rotate in and around that axis; and finally between movement and frozen stillness.

“Devices and materials which create the smooth, invisible transitions from shot to shot and space to space are fades done in the camera, changes in focus, backlighting modulating to frontal lighting, a window shutter which opens a slit of light in the shadow before it, and camera movement continuing over the cut. Nearer the end, superimpositions juxtapose in the space of one shot two spaces and times which overlap and define the distance between them. The film presents a few moments of visual beauty in the shifting network of a multitude of frames. Transforming the inert into the moving, Jacobs’ camera travels from form to form with delicacy and grace.”

(Lindley Page Hanlon, excerpt of essay published in “A History of the American Avant-Garde Cinema”, American Federation of Arts, 1976)

AIRSHAFT

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1967, 16mm, 18fps, silent, colour, 4 min

In memory of Judy Midler.

Single fixed-camera take looking out through fire-escape door into space between rears of downtown N.Y. loft buildings. A potted plant, fallen sheet of white paper, and a cat rest on the door-ledge. Cinematographer fingers intercept, deflect, and toy with the flow of light, the stuff of images, on their way to the lens. The flow in time of the image is interrupted, partially and then wholly dissolving into blackness; the picture re-emerges, the objects smear, somewhat double, edges break up. Focus shifts between foreground and background planes, an emphasis of the shaft-space in between. The fragile image shines forth one last time before dying out. Booed at open screening marathon of Vietnam War protest films, “For Life, Against the War.”

(Ken Jacobs, statement in “Films That Tell Time: A Ken Jacobs Retrospective”, American Museum of the Moving Image, 1989)

SOFT RAIN

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1968, 16mm, 18fps, colour, silent, 12 min

View from above is of a partially snow-covered low flat rooftop receding between the brick walls of two much taller downtown N.Y. loft buildings. A slightly tilted rectangular shape left of the centre of the composition is the section of rain-wet Reade Street, visible to us over the low rooftop. Distant trucks, cars, persons carrying packages, umbrellas sluggishly pass across this little stage-like area. A fine rain-mist is confused, visually, with the colour emulsion grain.

A large black rectangle following up and filling to space above the stage area is seen as both an unlikely abyss extending in deep space behind the stage or more properly, as a two dimensional plane suspended far forward of the entire snow/rain scene. Though it clearly if slightly overlaps the two receding loft building walls the mind, while knowing better, insists on presuming it to be overlapped by them. (At one point the black plane even trembles.) So this mental tugging takes place throughout. The contradiction of 2D reality versus 3D implication is amusingly and mysteriously explicit.

Filmed at 24fps but projected at 16fps the street activity is perceptively slowed down. It’s become a somewhat heavy labouring. The loop repetition (the series hopefully will intrigue you to further run throughs) automatically imparts a steadily growing rhythmic sense of the street activities. Anticipation for familiar movement-complexes builds, and as all smaller complexities join up in our knowledge of the whole the purely accidental counter-passings of people and vehicles becomes satisfyingly cogent, seems rhythmically structured and of a piece. Becomes choreography.

(Ken Jacobs, statement in Film-makers’ Cooperative Catalogue #5, 1971)

URBAN PEASANTS

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1975, 16mm, 18fps, b/w, sound on cassette, 50 min

My wife Flo’s family as recorded by her Aunt Stella Weiss. The title is no put down. Brooklyn was a place made up of many little villages; an East European shtetl is pictured here, all in the space of a storefront. Aunt Stella’s camera rolls are joined intact (not in chronological order). The silent footage is shown between two lessons in “Instant Yiddish”: “When You Go To A Hotel” and “When You Are In Trouble”.

(Ken Jacobs, statement in “Films That Tell Time: A Ken Jacobs Retrospective”, American Museum of the Moving Image, 1989)

“Even before the first image of Urban Peasants appears we have had a six minute lesson in Diaspora history called “Situation Three: Getting A Hotel”. (The assumption is mind-blowing: Where in the world, with the possible exception of Birobidzhan, would one ever need to call room service in Yiddish ?) A second excerpt, “Situation Eight: When You Are in Trouble”, provides the film’s double edged punch line: “I am an American … Everything is all right.” Jacobs’s deceptively simple juxtaposition makes it impossible to watch the homely clowning of his wife’s wartime, half-Americanised family without picturing the “situation” of their European counterparts.”

(Jim Hoberman, excerpt from “Jacob’s Ladder”, Village Voice, 1989)

GLOBE

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1969, 16mm, colour, sound on cassette, 22 min

Formerly titled Excerpt from the Russian Revolution

First film, to our knowledge, designed to appear in deep 3D via the Pulfrich Effect, a single dark plastic filter interfering with and absorbing most of the light going to the eye it’s held in front of (both eyes remaining open). For this film, because all foreground motion is to the right, and because we want depth to appear as it would in life, the filter (perhaps conveniently taped to an eyebrow) is to be held before the right eye. Film was shot with a standard movie-camera and is to be projected with no special devices or requirements. Depth-phenomena does depend on onscreen lateral motion, left / right shifting of pictured elements relative to each other. As with audio stereo, middle seating is best; depth will expand with distance from the screen.

Locale is the upper-middle-class Stair Development newly built to provide housing for the executive class of IBM in Binghampton, on northern New York State’s “snow belt”. A beautiful, hilly, forested area of the globe, ripe for ‘development’, though at present spared due to economic decline due to manufacturing having been moved offshore. Please note the absence of sidewalks, of corner stores, of neighbourhood schools and therefore of a neighbourhood. We see a near-absence of people. Garages are connected to homes; residents do not step out, they drive out, in order to shop (anonymously) at a choice of malls, to go to work or to school or to meet with friends, etc. (kids are driven out to “play-dates” at other kids’ homes or are taken to and picked up from organised after-school programmes; they never simply gather after-school with neighbourhood chums). Such are the prize lives of the area, the IBM winners. We Americans tend to be the first humans among the world’s groupings to be so experimented on. If we seem to adapt, willingly jettisoning prior social arrangements, the new life-style is deemed ready for export. Look for a Stair Development coming your way! But do remember, when Cultural Imperialism is discussed, that, because the wave rolls over us first, and we are the first to be sold on giving up our ways, it should not be thought of as American Cultural Imperialism. It’s the world’s Corporate Future, with America as test-site.

Audio is side A of the LP “The Sensuous Woman”, circa 1969. It illustrates the near-instant co-opting and commodifying of The Sexual Revolution.

(Ken Jacobs, 2000)

Also Screening:

Thursday 2 November 2000, at 7:30pm, Brighton Cinematheque

Tuesday 7 November 2000, at 6:30pm, Glasgow Film Theatre

Thursday 30 November 2000, at 7:30pm, Hull Screen

Monday 4 December 2000, at 6:10pm, Manchester Cornerhouse

Wednesday 6 December 2000, at 9pm, London Lux Centre

Tuesday 12 December 2000, at 6:30pm, Sheffield Showroom

Back to top

Date: 14 October 2000 | Season: Ken Jacobs Nervous System, Leeds Film Festival 2000

KEN JACOBS RETROSPECTIVE: PROGRAMME 2

Leeds International Film Festival

Saturday 14 October 2000, at 12:30pm

TOM, TOM THE PIPER’S SON

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1969-71, 16mm, 18fps, silent, b/w, & colour, 115 min

Cinematography assistant, Jordan Meyers. Negative matching assistant, Judy Dauterman. Florence Jacobs super-assisting throughout.

We had to work at night because of our skylight, but when Jordan wasn’t asleep at his feet at the Victor, projecting at the rear screen over Flo-in-bed, his eyes were open. Thank you again, Judy, for perseverance and loving good humour, and for encouraging and helping with the addition of the sliding film section.

Original 1905 film shot and probably directed by G.W. “Billy” Bitzer (and returned from limbo, rescued via Kemp Niver refilming a deteriorated paper print filed for copyright purposes with the Library of Congress.) It is most reverently examined here, with a new movie almost incidentally coming into being.

Ghosts ! Cine-recordings of the vivacious doings of persons long dead. The preservation of their memory ceases at the edges of the frame (a 1905 hand happened to stick into the frame … it’s preserved, recorded in a spray of emulsion grains). One face passes ‘behind’ another on the two-dimensional screen.

The staging and cutting is pre-Griffith. Seven infinitely complex cine-tapestries comprise the original film, and the style is not primitive, not un-cinematic, but an inspired indication of another, alternate path of cinematic development, its values only recently rediscovered. My camera closes in only to better ascertain the infinite richness (playing with fate, taking advantage of the loop-character of all movies, recalling and varying some visual complexes again and again for particular savouring), searching out incongruities in the story-telling (a person, confused, suddenly looks out of an actor’s face), delighting in the whole bizarre human phenomena of story-telling itself and this within the fantasy of reading any bygone time out of the visual crudities of film: dream within a dream!

And then I wanted to show the actual present of the film, just begin to indicate its energy. A train of images passes like enough and different enough to imply to the mind that its eyes are seeing an arm lift, or a door close; I wanted to “bring to the surface” that multi-rhythmic collision-contesting of dark and light two-dimensional force-areas struggling edge to edge for identity of shape … to get into the amoebic grain pattern itself – a chemical dispersion pattern unique to each frame, each cold still … stirred to life by a successive 16-24 f.p.s. pattering on our retinas, the teeming energies elicited (the grains ! the brains !) then collaborating, unknowingly and ironically, to create the always-poignant-because-always-past illusion.

(Ken Jacobs, statement in “Films That Tell Time: A Ken Jacobs Retrospective”, American Museum of the Moving Image, 1989)

“Anamnesis is a technical term referring to the recovery of anxiety-provoking incidents, a process that appropriately describes Jacobs’s extensive record of reworking of found footage. It begins in 1955 with the purchase of an analytical projector capable of variable speed projection in both forward and reverse. Evenings spent “toying” with this device, exploring the ‘inner workings” of the movie image culminated in the production of Tom, Tom the Piper’s Son (1969-71), a two-hour visual exegesis of a ten-minute 1905 Biograph Company film shot by Billy Bitzer. Still his best-known work, Tom, Tom became critically ensconced as an avatar of the minimalist trend in avant-garde cinema dubbed Structural Film, a label Jacobs vehemently rejects. His object, as it were, was not a dry demonstration of mechanical properties of the medium but a magical raising of the dead: “Ghosts! Cine-recordings of the vivacious doings of persons long dead.” Refilming the Billy Bitzer tableaux, pictorially modelled after Hogarth, Jacobs slows down and isolates individual figures, capturing their casual distractions, their sensual movements and metaphoric encounters with other actors or props. He freeze-frames, reverses the motion, delves into ostensibly blank portions of painted backdrops.

“The humorous market day fable of the original is transformed into a truly carnivalesque parade of outlandish poses melting into authentic gestures of pleasure and vice versa, a hide-and-seek game of narrative role-playing ballasted by abstract shapes and balletic repetitions. As a side dish to Jacobs’s swelling feast, the art-historically inclined viewer is treated to a successive evocation of compositional styles, a selective review of modern painting that runs from Goya to the Impressionists and Seurat to Abstract Expressionists such as Franz Kline. Hidden archaeological details of the original are played against the constant recognition of moment-to-moment processes of refilming: flares, the foregrounded projector bulb, the placement of the translucent screen and, in a sequence shot in colour, a plant decorating the filmmaker’s loft. The ebb and flow of temporal strata is matched by the play of flatness and illusionistic depth.”

(Paul Arthur, excerpted from “Creating Spectacle From Dross: The Chimeric Cinema of Ken Jacobs”, first published in American Cinematographer magazine, 1997)

Also Screening:

Thursday 7 December 2000, at 7pm, London Lux Centre

Back to top

Date: 14 October 2000 | Season: Ken Jacobs Nervous System, Leeds Film Festival 2000

KEN JACOBS RETROSPECTIVE: PROGRAMME 3

Leeds International Film Festival

Saturday 14 October 2000, at 3pm

INSTRUCTIONS TO AUDIENCE

In order to experience the added depth of the Pulfrich 3D effect, the viewer should use the “Eye Opener” filter during OPENING THE NINETEENTH CENTURY: 1896. “Passing through the tunnel mid-film, a red flash will signal you to switch your single Pulfrich filter before your right you to before your left (keep both eyes open). Centre seating is best: depth deepens viewing further from the screen. Handle filter by edges to preserve clarity. Either side of filter may face screen. Filter can be held at any angle, there’s no “up” or “down” side. Also, two filters before an eye does not work better than one, and a filter in front of each only negates the effects.”

PLEASE RETURN YOUR FILTER TO CINEMA STAFF AFTER THE SCREENING

THE WHIRLED

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1956-61, 16mm, b/w & colour, sound & silent, 15 min

Nasty overstuffed clogged and airless American fifties. The few good Hollywood films after the Left-dumping, The 5000 Fingers of Dr. T, The Sweet Smell of Success, etc., are skyscrapers on the Mojave. Overwhelmed, hopeless, it was a good time for irreverence. In particular, for art film in the vernacular, like an amusing letter, me to you. Sketchy, airy, anti-precious, without a lot of geniusing at the audience. Slices of imaginative life, not choosing to hide a N.Y. specific economic reality but I can dream, can’t I? Not anti-art, which my superiors, the critics of the period, assumed. To my bafflement. I had decided, with the examples of jazz improvisation and of action painting which would build on one impulsive stroke, and let things hang out indications of wrong turns towards the emerging clarity – not to edit and doll up the 100-foot camera rolls. But to let the film materials show, the Kodak perforations and start and end roll light flares; to feature the clicks and scratchings of the 78 r.p.m. records I pirated for accompaniment. Camera sequence as determined impulse upon impulse by the cinematographer seemed sensible to me, and to be respected. The off moments, vagaries, ’tis-human-toerrs, such beatings about the bush also delineated the bush; there was the example of Cezanne’s outlines, groping for the contour. Follow the impulses, I thought, and let appearances fall as they may. That’d be perfect enough.

(Ken Jacobs, statement in “Films That Tell Time: A Ken Jacobs Retrospective”, American Museum of the Moving Image, 1989)

THE DOCTOR’S DREAM

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1978, 16mm, b/w, sound, 27 min

Original found material, a bland fifties TV movie. What’s important to know is that, in re-cutting it, nothing was done to make a point or be funny. It was cut blind. That is, according to scheme. Unexpectedly, something was learned about how hot secret messages are smuggled through (social) customs.

Sequential progression along conventional lines has the magic effect of disguising from the observer the real matter at hand. At the same time, it’s what the observer is really drawn to. It’s veiled, which allows the observer to have a powerful response to it and at the same time not feel guilty due to the taboo strictures of society.

(Ken Jacobs, statement in “Films That Tell Time: A Ken Jacobs Retrospective”, American Museum of the Moving Image, 1989)

“… A quite different encounter with chance is registered in The Doctors Dream (78). Here an utterly vapid, sententious TV short from the Fifties about a country physician on an urgent house call to a sick child is reedited according to a simple formula. The opening shot of Jacobs’ revision is the exact median point in the narrative sequence and successive shots proceed toward either end, with the first and last shots placed next to each other at the finale. Even though a spectator may not grasp the precise ordering principle, it is clear that as Dream unfolds the gaps in narrative logic between adjacent shots become increasingly attenuated and bizarre. With time wrenched out of joint, conventional markers of cause and effect get waylaid, producing weirdly expressive conjunctions. The sick girl’s brother watches as she has blood drawn, then in the next shot stands weeping and praying for her deliverance; did the medical procedure cause her demise ? Slightly later, the girl jack-knifes through a series of shots: first gravely ill, then blithely dusting furniture, then once more on death’s door. Her unsettling dance of swoons and revivals hints at something more unearthly than the “Higher Power” invoked by the pious doe as her true salvation.

“Once again syntax is made strange as, for instance, clusters of medium shots of roughly the same subject bond in a fashion never permitted by standard editing practices. In this Kuleshov experiment in reverse, poetic themes and unsavoury character motives seem to leap from the restirred detritus: an emphasis on time and / as vision prompted by repeated close-ups of the doctor’s pocket watch and his fiddling over a microscope; the father looking daggers at the benevolent man of science, perhaps for good reason since his bedside manner takes on a treacly erotic dimension. As in many otherwise dissimilar Jacobs projects, one can in Dream sense with a veiled clarity the narrative gears at work, the interchangeable factory parts of master-shot and shot-countershot as they churned out an easily digestible product. On this occasion, however, what remains is less a cruel unmasking than a redemption – bad acting saved by dreamlike disjunctions, stupid lines recuperated by sinister associations.”

(Paul Arthur, excerpted from “Creating Spectacle From Dross: The Chimeric Cinema of Ken Jacobs”, first published in American Cinematographer magazine, 1987)

KEATON’S COPS

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1991, 16mm, b/w, silent, 23 min

Original film by Edward F. Cline and Buster Keaton, 1922.

New arrangement by Ken Jacobs, assisted by Florence Jacobs, 1991.

Some films are a joy to look at repeatedly, and also separately in their various parts. Here we see the bottom fifth of COPS. Our intention was to interfere with narrative coherence, to deny narrative dominance; to release the mind for a while from story and the structuring of incident, compelling as it is in Keaton’s masterly development. Our wide-screen re-filming limits seeing to the periphery of story, moves us from the easy reading of an illustrated text on to active seeing: what to make of this! Reduced information means we now must struggle to identify objects and places and, in particular, spaces. A broad tonal area remains flat, clings to the screen, until impacted upon by a recognisable something: Keaton smashes into it, say, and so it’s a wall, or a foot steps on it or a wheel rolls across it and it’s a road ! Shapes come into their own, odd and suggestive entities hinting at their own subconscious sub-narratives. We become conscious of a painterly screen alive with many shapes in many tones, playing back and forth between the 2D screen-plane and representation of a 3D movie-world, at the same time that we notice objects and activities (Keaton sets his comedy amidst actual street traffic) normally kept from mind by the moviestar-centred moviestory.

(Ken Jacobs, 2000)

PERFECT FILM

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1985, 16mm, b/w, sound, 22 min

TV newscast discard, out-takes of history reprinted as found in a Canal Street bin, with the exception of boosting volume second half.

A lot of film is perfect left alone, perfectly revealing in its un- or semi- conscious form. I wish more stuff was available in its raw state, as primary source material for anyone to consider, and to leave for others in just that way, the evidence uncontaminated by compulsive proprietary misapplied artistry. “Editing”, the purposeful “pointing things out” that cuts a road straight and narrow through the cine-jungle; we barrel through thinking we’re going somewhere and miss it all. Better to just be pointed to the territory, to put in time exploring, roughing it, on our own. For the straight scoop we need the whole scoop, no less than the clues entire and without rearrangement.

O, for a Museum of Found Footage, or cable channel, library, a shit-museum of telling discards accessible to all talented viewers/auditors. A wilderness haven salvaged from Entertainment.

(Ken Jacobs, statement in “Films That Tell Time: A Ken Jacobs Retrospective”, American Museum of the Moving Image, 1989)

“For Jacobs, “found” footage has less to do with appropriation than with appreciation. The bluntly titled Perfect Film is a 22-minute roll Jacobs discovered in a Canal Street junk bin and which he exhibits unaltered – an apparently random series of interviews and relevant exteriors taken by a TV news crew in the aftermath of Malcolm X’s assassination. Perfect Film opens with a white reporter interviewing a black eyewitness (himself a reporter), and everything in this unmediated slice of celluloid takes on equal weight – the witness’ faraway look, the way his experience becomes narrative, the camera-attracted mob (a Weegee crowd unfolding in time), the choice of camera angle, the interlocutor’s tone. Meanwhile other voices are heard. A white police inspector attempts to direct his presentation. A silent montage of streets, crowds, and cops sets off the recurring interviews. Even the dead Malcolm appears in a 30-second clip to say that Elijah Muhammad has given the order that he is to be killed.

“More than a time capsule, Perfect Film is a study of how news is made, literally. These outtakes have their own integrity. There’s a structure here, even a revelatory drama. What’s “perfect” is the demonstration that an anonymous work print found in the garbage can be as multi-layered and resonant, revealing and mysterious as a conscious work of art.

“I learned this – and a great deal more – from Jacobs, with whom I studied for several years at the height of the 60s. The era suited his outsized temperament as a teacher, Jacobs would never be mistaken for Mr. Chips. (Displeased with an article I wrote in the Voice, he once sent me a letter enumerating his accomplishments and adding, “I wish I could take them all away from you.”)”

(Jim Hoberman, excerpt from “Jacob’s Ladder”, Village Voice, 1989)

OPENING THE NINETEENTH CENTURY: 1896

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1990, 16mm, colour, sound, 9 min

Shafting the screen: the projector beam maintains its angle as it meets the screen and keeps on going, introducing volume as well as light, just as in Paris, Cairo and Venice of a century ago happen to pass.

(Ken Jacobs, statement in London Film-Makers’ Co-Op Catalogue, 1993)

Scott MacDonald: Am I right that in Opening the Nineteenth Century: 1896 we see exactly the same footage forward and right-side up, then backward and upside down?

Ken Jacobs: Yes. The imagery is a collection of what were supposedly the first travelling shots by the Lumière company. The material switches directions, and you switch your filter from one eye to the other, halfway through. In the original sequence there were movements to the right and to the left, but the 3D effect only works when the filter is in front of the eye that corresponds to the direction of the movement, that is, so that when the filter is over the right eye, the foreground figures move in that direction. Some images are turned upside down to maintain the direction. The second pass is the same images in the same order, but the whole film is turned upside down and inside out: it ends with what was the first shot of the film, and whatever was upside down the first time is now right-side up and vice versa. The film is entirely symmetrical. Recently we’ve been toying around with train whistles. Right now there’s a train whistle at the very beginning, and another one halfway through, which is a signal to the audience to switch the filter to the other eye.

(Scott MacDonald interviews Ken Jacobs in “A Critical Cinema 3”, University of California Press, 1988)

Also Screening:

Friday 9 October 2000, at 6:45pm, Glasgow Film Theatre

Thursday 7 December 2000, at 9pm, London Lux Centre

Monday 11 December 2000, at 6:10pm, Manchester Cornerhouse

Thursday 14 December 2000, at 7:30pm, Hull Screen

Back to top

Date: 15 October 2000 | Season: Leeds Film Festival 2000

TALE OF A VISIONARY: SHORT FILMS BY SHUJI TERAYAMA

Sunday 15 October 2000, at 6pm

Leeds City Art Gallery

Shuji Terayama is a legendary and unique figure in the cultural history of Japan. From the age of 19, he was a celebrated haiku and tanka poet and went on to become an award winning radio dramatist, a distinguished photographer, a respected boxing correspondent and one of the country’s most successful horse racing tipsters. In 1967, keen to break away from words and letters, he formed the forward thinking Tenjosajiki experimental theatre group, in order to “write poems with bodies”, and soon became renowned for his original and controversial performances. The troupe often comprised of midgets, freaks, runaways, vagrants and obese misfits, and the plays challenged the most progressive notions of contemporary theatre. The works were rarely performed in conventional auditoriums, and were more likely to be staged in the streets of Tokyo, or by leading audiences into private houses. The plays were non-narrative, disjointed and often vulgar, regularly descending into violence or fantastic orgies of naked flesh.

Not content with scandalising the theatre world, Terayama moved into filmmaking and his debut Nego-Gaku (Catology, 1962) set the pace for future productions, being a political fable about a cat being tortured by children and a dwarf. The central themes of Terayama’s films, as with much of his theatre work, are the need to overthrow and discredit authority, the tyranny of the family, the torment of adolescence and memories of sexual experiences. In 1964, his book “Abandon Your Homes!” openly encouraged teenagers to runaway and revolt again their parents and the conventions of Japanese tradition and society, a proposition explored in his first feature film, the unpredictable collage Sho O Suteyo Machi E Deyo (Throw Away Your Books, Let’s Go Into The Streets, 1971). He was a prolific maker of short films, which depict an even more personal and idiosyncratic vision than his five bizarre features, and the six films in this brief retrospective illustrate various aspects of Terayama’s radical style.

His most notorious film is Tomaten-Ketchup Kotei (Emperor Tomato Ketchup, 1972) in which pre-pubescent children lead a revolution against consumerism and bring about a new totalitarian state where grown-ups may be tied up, beaten and raped. This exploration of the taboo is told in a hallucinatory style, reminiscent of Jack Smith’s controversial experimental film Flaming Creatures (1962).

Shuji Terayama died in 1983 at the age of 47, having suffered from nephritis since his teenage years.

Shuji Terayama, Chofuku-Ki (16+-1), 1974, 15 min

Shuji Terayama, Tomato-Ketchup Kotei (Emperor Tomato Ketchup), 1970, 26 min

Shuji Terayama, Keshigomu (The Eraser), 1977, 20 min

Shuji Terayama, Hoso-Tan (Tale of The Smallpox), 1975, 31 min

Shuji Terayama, Issunboshi O Kijutsusuru Kokoromi (An Attempt To Describe The Measure Of A Man), 1977, 15 min

Shuji Terayama, Kage No Eiga: Nito Onna (Shadow Film: A Woman With Two Heads), 1977, 20 min

This programme subsequently screened as two separate programmes at London ICA Cinema and Brighton Cinematheque.

Back to top

Date: 19 October 2000 | Season: Leeds Film Festival 2000

APPARITIONS OF CLÉMENTI

Thursday 19 October 2000, at 6pm

Leeds City Art Gallery

To honour the memory of the Pierre Clémenti, who died last year, a rare screening of his very personal experimental films. The flamboyant French actor is well-known to aficionados of European cinema, as he has appeared in important films by directors such as Visconti (The Leopard, 1963), Bunuel (The Milky Way, 1969), Bertolucci (The Conformist, 1970), and Jancso (The Pacifist, 1971). His acting ability may have been limited, but his sultry, bohemian good looks meant he regularly played small but significant parts, belatedly receiving his first major starring role in Benjamin (1967) by Michel Deville, opposite Catherine Deneuve (together again following Bunuel’s Belle de jour the previous year). Clémenti seemed to shy away from box-office success and favoured artistically challenging work, appearing in several early existential films by his friend Philippe Garrel, and such difficult works as Makavejev’s Sweet Movie (1974) and Pasolini’s Pigsty (1969).

In his own films, he pursues an intimate, poetic vision, weaving a complex tapestry of fact and fantasy. Influenced by the diary films of Jonas Mekas and Taylor Mead, and excited by screenings of the American underground, Clémenti created his own informal and psychedelic cinema style. Visa de censure n° X (1967-75) was named after the ‘visa de controle’, a document that must be issued for each film before public screenings in France, a country which at that time was over zealous in restricting works that were politically or socially undesirable. This air of extreme censorship meant that few French personal films were made in the late 1960’s, a period which saw the most experimental film activity in other countries. This first film is an eclectic mix of superimposition, neon light traces & time-lapse photography, combining real life footage with theatrical invention to capture an evocative memory of a free-wheeling era.

Always courting controversy and flaunting a disregard for authority, in the late 60s Clémenti was active in the radical Parisian youth movement and in 1971 was arrested in Italy on drugs charges. Following his incarceration he began to work on New Old (1979), a film and book which chronicled his activities as an actor and the everyday events surrounding the conception of his only fiction film A L’ombre de la canaille bleu (finally realised in 1987). Feeling he was at a point of no return, Clémenti embarked upon this stark confessional.

After his heydey, Clémenti continued to appear in numerous feature films. Some, like The Son Of Amr is Dead (Jean Jacques Adrien, 1978) were artistic and critical successes, but as his looks faded, he became less in demand and was forced to lower his standards, stumbling through rarely shown European productions as ill-health incapacitated his ability to perform. His last role was a minor part in Hideous Kinky (1998), a tale of enlightenment that must have been a sore reminder of his own spiritual journeys of the past. Clémenti died of cancer, aged 57, in December 1999.

Pierre Clémenti, Visa de censure n° X, France, 1967-75, 16mm, colour, sound, 42 min

Pierre Clémenti, New Old, France, 1978-79, 16mm, colour, sound, 64 min

This programme subsequently screened at London ICA Cinema and Brighton Cinematheque.

Back to top