Date: 13 June 2003 | Season: California Sound/California Image

CALIFORNIA SOUND/CALIFORNIA IMAGE

13—19 June 2003

London Barbican Screen

From Hollywood to San Francisco: The West Coast and the Avant-Garde

A trip through 70 years of artists’ filmmaking in, on and around the American West Coast, featuring expressionist experiments, pioneering psychodrama, freewheeling Beat Culture and the psychedelic explosion. The post-war avant-garde began in Los Angeles with the revolutionary trance films of Kenneth Anger, Maya Deren and Gregory Markopoulos, but San Francisco soon established itself as a major centre in the 1960s when Bruce Baillie, Chick Strand and Bruce Conner founded Canyon Cinema, organising screenings and distribution. This unique season includes rare works by these filmmakers, and many others including Jordan Belson, Ernie Gehr, George Kuchar and Gunvor Nelson, plus Andy Warhol’s scenario based on the real-life arrest for shoplifting of Ecstasy starlet Hedy Lamarr.

CALIFORNIA SOUND/CALIFORNIA IMAGE is curated by Mark Webber for Barbican Screen and LUX.

Date: 13 June 2003 | Season: California Sound/California Image

WEST COAST BEAT

Friday 13 June 2003, at 7pm

London Barbican Screen

The cellular, celluloid merger of the literary and artistic underground, featuring Michael McClure, Jack Hirschman, Henry Jacobs, Jay DeFeo, Wallace Berman, Christopher MacLaine. Beat Poets + Beat Artists = Beat Cinema.

Larry Jordan, Visions of a City, 1957/78, sepia, sound, 7 min

Frank Stauffacher, Sausalito, 1948, b/w, sound, 10 min

Wallace Berman, Untitled (Aleph), 1958/76, colour, silent, 10 min

Bruce Conner, The White Rose, 1967, b/w, sound, 7 min

Jane Belson, Odds and Ends, 1958, colour, sound, 5 min

Christopher MacLaine, The End, 1963, b/w & colour, sound, 35 min

Henry Hills, Kino Da!, 1981, b/w, sound, 4 min

PROGRAMME NOTES

WEST COAST BEAT

Friday 13 June 2003, at 7pm

London Barbican Screen

VISIONS OF A CITY

Larry Jordan, 1957/78, sepia, sound, 7 min

“The protagonist, poet Michael McClure, emerges from the all-reflection imagery of glass shop and car windows, bottles, mirrors, etc. in scenes which are also accurate portraits of both McClure and the city of San Francisco in 1957. At the same time it is a lyric and mystical film, building to a crescendo of rhythmically intercut shots of McClure’s face, seemingly trapped on the glazed surface of the city. Music by William Moraldo. I don’t think of this as an ‘early film’ anymore, since it never came together until 1978. Now it’s tight.” —Larry Jordan

SAUSALITO

Frank Stauffacher, 1948, b/w, sound, 10 min

“This film is part ‘city symphony’ and part ‘outtakes from an experimental film’. Sausalito is the picturesque waterfront town across the Golden Gate Bridge from San Francisco and has functioned, during times of low rent, as an artists’ colony. It is the kind of place that produces postcard-perfect images from practically any visual perspective: point the camera and the result will be ocean bay, fog, sailboats, waves, seashells, rocky beach, inclined streets, wooden piers, antique shops, dancer’s legs and California shore birds. Stauffacher has combined these elements through a technique of abrupt visual and audio crosscutting and juxtaposition that helps transcend the clichéd material. Along the way he experiments with slow motion, split-screens and superimposition, all of which are lightened by a constant thread of whimsicality and wit.” —Museum of Modern Art, New York

UNTITLED (ALEPH)

Wallace Berman, 1958/76, colour, silent, 10 min

“Figure moving through darkness suddenly illuminated in a random harsh light … Young, hawk-face intensity, straight ahead stare, super cool, zoot suit type attire topped by brush cut hair straight up, with young woman in tight black dress disappearing suddenly in room behind stage … ‘Who was that?’ ‘That’s Wallace Berman’ came the anonymous reply with an authority that implied all had been said.” —Walter Hopps

THE WHITE ROSE

Bruce Conner, 1967, b/w, sound, 7 min

“Begun in 1958, The Rose was DeFeo’s almost exclusive obsession for seven years. Composed of one ton of mostly white and grey paint that reaches depths of up to eight inches, The Rose is certainly one of the most dense and massive paintings ever made. Nevertheless, the work’s sublimity lies precisely in the fact that, despite this sheer accumulation of matter, it exudes a profound sense of spaciousness and light. Even before it was finished, The Rose had acquired legendary status: Dorothy Miller, curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, desperately wanted the work for her landmark exhibition Sixteen Americans (an exhibition which helped to launch the careers of Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Ellsworth Kelly, Louise Nevelson, and Frank Stella), and Bruce Conner made a film, The White Rose, about the painting’s removal – by forklift – from the artist’s studio in 1965.” —Berkeley Art Museum

ODDS AND ENDS

Jane Belson, 1958, colour, sound, 5 min

“Live action and animation are combined into a total abstract structure. The accompanying narration [by Henry Jacobs] is a tongue-in-cheek dissertation on poetry and jazz, in which an anonymous, eminent and indefatigable rationalist talks himself into a corner. ‘I don’t know just what to say other than that I have been extremely impressed with the works of other filmmakers and I just got high and put it together’.” —Amos Vogel, Cinema 16, quoting Jane Belson Conger

THE END

Christopher MacLaine, 1963, b/w & colour, sound, 35 min

“What MacLaine did for money, God only knows – begged on the streets, mooched, finally robbed and stole. I use both ‘robbed’ and ‘stole’ because he had both these qualities of a thief. He was always desperate. He sang and read poetry in the bars. He read poetry with jazz when that became popular toward the end of the Beat movement in the late 1950s. He always thought of himself as a poet. His poems, however, were out-spewings of rage and wrathfulness. His conversation was always more poetic than his poems. But the man had an innate and powerful sense of rhythm, and that was the main strength of his poetry. I don’t think he really wrote poetry; but he tried to be a poet in a way very similar to Artaud, and he failed for similar reasons. I do not know if MacLaine ever thought of himself as the ‘Artaud of San Francisco’, but he certainly did have an affinity with him: he courted madness and he finally got it.” —Stan Brakhage, Film at Wit’s End

NB: New prints of all four films by Christopher MacLaine’s will be presented in a Lux touring programme in the autumn

KINO DA!

Henry Hills, 1981, b/w, sound, 4 min

KINO DA! (ah, ke, ke) KINO DA!

The Dead die die dada low king quanto zong

MOVE! (ur, ur)

Grey todays it-a clear to the quick ear, quicker z’heels

The Poe (pay, po, pee, pick-pick), nuf of “D” yet

Call Vertov

(beep, beep)

Eisenstein even

& viterulably cheeness of a ram innerwear

(airs; hen)

Time, Time, Money

d-d-d-

junk rock did travel & falls

(spring)

Fall

Spring is the simplest inflationary dime.

Be in everything Joy, in experimental & (thus)

proletarian & wwea air of airs

at this school of po’try-painting

CUT!

To know

toe

no! no! MONTAGE (nadazha), in any instant

(instant) of the writing of Stein & the facts of that

(tle) kind.

FEEL IT! (the steak)

yes, ache, in trends & whatevers.

Mmmm-pah-ah Cops, man in case (nnn), man

nnn.

(KO) be-a mayu po pony;

.(KO) be-a (what?) o-long kind.

GO! (be what) OM, prose, Pentacost; be what this there the (pause) & (serious pause) the neb with a gram of ire illia-it’s still justs Jah.

Viparko r-rrr re ad adici, yes!

YES!

ssssssssssane!

mmmm keybo z’Kruchchev.

Back to top

Date: 14 June 2003 | Season: California Sound/California Image

HOLLYWOOD BE THY NAME

Saturday 14 June 2003, at 7pm

London Barbican Screen

Four of the avant-garde’s most momentous flirtations with the glamorous world of The Movies. The dark shadow of Tinseltown looms large on the horizon.

Robert Florey & Slavko Vorkapich, The Life and Death of 9413 – A Hollywood Extra, 1927, b/w, silent, 15 min

George Kuchar, I, An Actress, 1978, b/w, sound, 10 min

Andy Warhol, Hedy (The Shoplifter), 1966, b/w, sound, 66 min

Kenneth Anger, Puce Moment, 1949/70, colour, sound, 7 min

PROGRAMME NOTES

HOLLYWOOD BE THY NAME

Saturday 14 June 2003, at 7pm

London Barbican Screen

THE LIFE AND DEATH OF 9413 – A HOLLYWOOD EXTRA

Robert Florey & Slavko Vorkapich, 1927, b/w, silent, 15 min

“A Hollywood Extra was made by three people: Slavko Vorkapich, an expatriate Yugoslavian commercial artist turned cinéaste; Robert Florey, an expatriate French journalist; and Gregg Toland, an assistant cameraman at MGM. Shot over several weekends in Vorkapich’s kitchen at a total cost of $97, it combined live action and special effects to recount the fate of an extra who hopes to make a career as an actor, and also to sketch the conditions of studio production and the architectural fabric of the city at large. Hollywood dehumanises the hopeful actor and eventually destroys him. He is reduced to a number (which is written on his forehead), he fails to find work and, hounded by creditors and continually humiliated by the stars, he sinks into poverty and dies. Only when he reaches Heaven is the stigma removed from his brow.” —David E. James, Unseen Cinema

I, AN ACTRESS

George Kuchar, 1978, b/w, sound, 10 min

“This film was shot in 10 minutes with four or five students of mine at the San Francisco Art Institute. It was to be a screen test for a girl in the class. She wanted something to show producers of theatrical productions; the girl was interested in an acting career. By the time all the heavy equipment was set up the class was just about over; all we had was 10 minutes. Since 400 feet of film takes 10 minutes to run through the camera … that was the answer: Just start it and don’t stop till it runs out. I had to get into the act to speed things up so, in a way, this film gives an insight into my directing techniques while under pressure.” —George Kuchar

HEDY (THE SHOPLIFTER)

Andy Warhol, 1966, b/w, sound, 66 min

“Starring Mario Montez as ‘Hedy’, Mary Woronov as the policewoman, Harvey Tavel as the judge, Ingrid Superstar as the sales lady, Ronald Tavel as the walk-on, and the five husbands are played by Gerard Malanga, Rick Lockwood, James Claire, Randy Borscheidt, David Myers. Jack Smith plays the soothsayer. Arnold Rockwood, of Flaming Creatures fame, plays the surgeon. The story of a wealthy and beautiful woman getting a face-lifting to look more beautiful, and then caught at shop-lifting, to face her former five husbands and her past climbing up and down the ladder of success. Scenario by Ronald Tavel. Musical soundtrack by John Cale and Lou Reed.” —New York Film-Makers’ Cooperative Catalogue No.4

PUCE MOMENT

Kenneth Anger, 1949/70, colour, sound, 7 min

A fragment of the uncompleted feature film Puce Women. “Puce Women was my love affair with mythological Hollywood. A straight, heterosexual love affair, no bullshit, with all the great goddesses of the silent screen. They were to be filmed in their actual houses; I was, in effect, filming ghosts. When I couldn’t get any bread from [Arthur] Freed or [Gene] Kelly at MGM the project was doomed, because a freeway to the San Fernando Valley was put through all those lovely 1920 houses. That was a sad day for Hollywood, the beginning of the end, when Whitley Heights went. I’m a conservative, meaning that I cherish things of value. This places me at the antipodes of a cheap hustler like Andy Warhol, who is the garbage merchant of our time.” —Kenneth Anger interviewed by Tony Rayns

Back to top

Date: 15 June 2003 | Season: California Sound/California Image

FILM TIME / FILM MOTION

Sunday 15 June 2003, at 7pm

London Barbican Screen

West Coast structuralism meets avant-garde vagary as time is lapsed, stretched, condensed and compressed using the methods and mechanics of motion pictures.

Morgan Fisher, The Director and His Actor Look at Footage Showing Preparations for an Unmade Film: 2, 1968, colour, sound, 15 min

Gary Beydler, Pasadena Freeway Stills, 1974, colour, silent, 6 min

Ernie Gehr, Eureka, 1974, b/w, silent, 30 min

Michael Rudnick, Panorama, 1982, colour, sound, 13 min

Bruce Baillie, Castro Street, 1967, b/w & colour, sound, 10 min

Owen Land (formerly known as George Landow), A Film of their 1973 Spring Tour commissioned by Christian World Liberation Front of Berkeley, California, 1974, b/w, sound, 11 min

PROGRAMME NOTES

FILM TIME / FILM MOTION

Sunday 15 June 2003, at 7pm

London Barbican Screen

THE DIRECTOR AND HIS ACTOR LOOK AT FOOTAGE SHOWING PREPARATIONS FOR AN UNMADE FILM: 2

Morgan Fisher, 1968, colour, sound, 15 min

“Narrative filmmaking was my original interest, and it’s still an interest. I make no apologies for it. It’s always been a part of my work, however obliquely. In fact if there were no narrative filmmaking and no Industry, I don’t think I could do work. I don’t mean this in the obvious sense: that – as would certainly be the case – without the Industry, and industry in general, there would be no film or equipment and hence no independent filmmaking (in that respect we are all at the mercy of industrial capitalism, whose sympathies and motives are directed elsewhere). I just mean that for me the Industry is a point of reference and a source, in both a positive and a negative sense, something to recognise and at the same time react to.” —Morgan Fisher

PASADENA FREEWAY STILLS

Gary Beydler, 1974, colour, silent, 6 min

“The film begins with Beydler placing photographs one by one into a rectangular frame. The prints appear to be the same image: traffic entering a tunnel on the Pasadena freeway. Gradually he inserts and removes the photos more quickly. Then the hand movements are eliminated, and the stills quickly build up speed like a locomotive until the cars are whisking through the tunnel and the audience becomes amazed, by Beydler’s cleverness, and by their own ‘Aha!’ responses as a confusing premise is revealed. Beydler’s involvement with motion and time shows his comprehension of the film medium – its uniqueness and difference from every other art form.” —Sandy Ballatore, Artweek

EUREKA

Ernie Gehr, 1974, b/w, silent, 30 min

“This is a re-filming of a remarkable movie depicting Market Street, San Francisco, around the turn of the century. The original film consisted of one long continuous take recorded from the front of a moving trolley from approximately Seventh Street all the way to the Embarcadero. I extended each frame six to eight times, full-frame, and increased the contrast and the light fluctuations. To some degree, the original film has obviously been transformed, but I hope that this simple muted process allowed enough room for me to make the original work ‘available’ without getting too much in the way. This was very important to me, as I tend to see what I did, in part, as the work of an archaeologist, resurrecting an old film as well as the shadows and forces of another era.” —Ernie Gehr

PANORAMA

Michael Rudnick, 1982, colour, sound, 13 min

“The most literal attempt to honour San Francisco’s history as a source of the American photographic panorama is Michael’s Rudnick’s Panorama, which was shot over the period of a year (Spring 1981 to Spring 1982) from inside and around his fourth-floor apartment in the Russian Hill area. Rudnick filmed in time-lapse, alternating between leftward pans (he built a device to ensure smooth panning) and a non-moving camera: while the alternation is regular, it is not rigorously systematic, though the overall arrangement is chronological. Within the overall rhythms of Panorama, Rudnick presents a range of visual experiences, some of them panoramic in the most conventional sense – time-lapse pans across broad urban vistas – others quite intimate, at least visually.” —adapted from Scott MacDonald, The Garden in the Machine

CASTRO STREET

Bruce Baillie, 1967, b/w & colour, sound, 10 min

“Technically, when I made Castro Street, I went into the field again with my ‘weapon’, my tools. I collected a couple of prisms and a lot of glasses from my mom’s kitchen, various things, and tried them all in the Berkeley backyard one day. I knew I wouldn’t have access to a laboratory that would allow me to combine black-and-white and colour, and I was determined to do it myself. I went after the soft colour on one side of Castro Street where the Standard Oil towers were; the other side was the black-and-white, the railroad switching yards. I was making mattes using high contrast black-and-white film that was used normally for making titles. I kept my mind available so that as much as one can know, I knew about the scene I just shot when I made the next colour shot. What was white would be black in my negative, and that would allow me to matte the reversal colour so that the two layers would not be superimposed but combined.” —Bruce Baillie in Scott MacDonald, A Critical Cinema

A FILM OF THEIR 1973 SPRING TOUR COMMISSIONED BY CHRISTIAN WORLD LIBERATION FRONT OF BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA

Owen Land (formerly known as George Landow), 1974, b/w, sound, 11 min

“He manages to set off a uniquely hypnotic experience. The viewer discovers the possibility of looking at the film like a ‘winkie toy’, seeing first one view then flashing to another. Because all footage is sound sync, this screening process hones our responses, until we see more in Land’s 3-frame sequences than we would in hour long doses of ‘normal’ time. Like the study of signs, this study of seconds yields a knowledge of people and truth inaccessible to more common observation.” —B. Ruby Rich

Back to top

Date: 17 June 2003 | Season: California Sound/California Image

IN BETWEEN MOMENTS

Tuesday 17 June 2003, at 7pm

London Barbican Screen

Personal emotions and experiences are documented and disclosed in three intimate films of private moments. Luminous glances at everyday life and a sensitive affirmation of female sensuality.

Nathaniel Dorsky, Variations, 1992-98, colour, silent, 24 min (18fps)

Chick Strand, Soft Fiction, 1979, b/w, sound, 54 min

Warren Sonbert, Noblesse Oblige, 1981, colour, sound, 25 min

PROGRAMME NOTES

IN BETWEEN MOMENTS

Tuesday 17 June 2003, at 7pm

London Barbican Screen

VARIATIONS

Nathaniel Dorsky, 1992-98, colour, silent, 24 min (18fps)

“Variations shows us glimpses of the world through an infinite eye. We see the forms of the world in their beautiful material immediacy: a cigarette on the floor, the brightness of white geese in the water, a shadowy chess board, a dog intently waiting for its owner with an expression of pure desire. But beyond the immediacy, the abstract poetic connections between shots suggest commonality of form – everything has a form –and in this sense all things are united. But we can and do still enjoy the pleasure of the visual differences, a pleasure that is, in turn, enhanced by the existence of similarity. Our act of seeing and our realisation of a playful interchange between similarity and difference seem more vital to our viewing of Variations than the notion of either self-expression or personal projection.” —Sarah Markgraf and Gregg Biermann, Millennium Film Journal

“What tender chaos, what current of luminous rhymes might cinema reveal unbridled from the daytime word? During the Bronze Age a variety of sanctuaries were built for curative purposes. One of the principal activities was transformative sleep. This montage speaks to that tradition.” —Nathaniel Dorsky

SOFT FICTION

Chick Strand, 1979, b/w, sound, 54 min

“Chick Strand’s Soft Fiction is a personal documentary that brilliantly portrays the survival power of female sensuality. It combines the documentary approach with a sensuous lyrical expressionism. Strand focuses her camera on people talking about their own experience, capturing subtle nuances in facial expressions and gestures that are rarely seen in cinema. The title Soft Fiction works on several levels. It evokes the soft line between truth and fiction that characterises Strand’s own approach to documentary, and suggests the idea of soft-core fiction, which is appropriate to the film’s erotic content and style. It’s rare to find an erotic film with a female perspective dominating both the narrative discourse and the visual and audio rhythms with which the film is structured. Strand continues to celebrate in her brilliant, innovative personal documentaries her theme, the reaffirmation of the tough resilience of the human spirit.” —Marsha Kinder, Film Quarterly

NOBLESSE OBLIGE

Warren Sonbert, 1981, colour, sound, 25 min

“Because most of the shots in Noblesse Oblige last no more than several seconds, the elliptical linkage of these ritualistic images and the interspersing of numerous shots of city streets, subways, skyscrapers, ships, airplanes, bridges, oil derricks, trees, mountain tops, etc. cumulatively suggest a sort of visual democracy. And this visual democracy, apparent throughout Sonbert’s mature work, underscores the relativity of all perceptions. What distinguishes Noblesse Oblige from its predecessors is its juxtaposition of symbols of American democracy, such as the Washington Monument, the Capitol Building and the Lincoln Memorial, with images of angry rioters, disconsolate mourners, masses of demonstrators and television reporters. […] Part of the ‘submerged story’ of Noblesse Oblige traces the shock and grief of San Franciscans following the assassinations of Harvey Milk and George Moscone and the outrage of the city’s gay community in the wake of the assassin’s conviction for manslaughter rather than murder. The candlelight parade occurred just after the murders; the storming of City Hall by indignant protestors followed the jury’s decision; the reception hosted by Diane Feinstein took place after she replaced Moscone as Mayor.” —David Davidson, Millennium Film Journal

Back to top

Date: 18 June 2003 | Season: California Sound/California Image

LOS ANGELES IN THE FORTIES

Wednesday 18 June 2003, at 7pm

London Barbican Screen

Trance and psychodrama, Surrealist montage, symbolism and sexual longing: The beginnings of the modern avant-garde and a new creative film language.

Maya Deren, Meshes of the Afternoon, 1943, b/w, silent, 14 min

Curtis Harrington, Fragment of Seeking, 1946, b/w, sound, 14 min

Kenneth Anger, Fireworks, 1947, b/w, sound, 15 min

Gregory Markopoulos, Psyche, 1947-48, colour, sound, 25 min

“In Los Angeles in 1947, while Kenneth Anger was editing Fireworks, Gregory Markopoulos began to shoot Psyche, the first film of his trilogy Du Sang de la Volupté et de la Mort. […] A few months before he began shooting Psyche, he had assisted Curtis Harrington in making his first film, Fragment of Seeking, where a young man pursues an elusive blonde woman through a maze of corridors reminiscent of Maya Deren’s pursuit of the mirror-faced figure in Meshes of the Afternoon. —P. Adams Sitney, Visionary Film

PROGRAMME NOTES

LOS ANGELES IN THE FORTIES

Wednesday 18 June 2003, at 7pm

London Barbican Screen

MESHES OF THE AFTERNOON

Maya Deren, 1943, b/w, silent, 14 min

“The cinema of Maya Deren delivers us from the studios: it presents our eyes with physical facts which contain profound psychological meaning; it beats out within our hearts a time which alternates, continues, revolves, pounds, or flies away … Poetry, after all, is the feast which life offers those who know how to receive with their eyes and hearts, and understand.” —Le Corbusier

FRAGMENT OF SEEKING

Curtis Harrington, 1946, b/w, sound, 14 min

“A classic West Coast experimental psychodrama second only in importance to Kenneth Anger’s Fireworks as the leading example of Freudian surrealism produced during the experimental film movement of the 1940s. It deals with teenage narcissism and latent homosexuality, with the film artist portraying the protagonist.” —Creative Film Society catalogue

FIREWORKS

Kenneth Anger, 1947, b/w, sound, 15 min

“In Fireworks I released all the explosive pyrotechnics of a dream. Inflammable desires dampened by day under the cold water of consciousness are ignited that night by the libertarian matches of sleep and burst forth in showers of shimmering incandescence. These imaginary displays provide a temporary release. A dissatisfied dreamer awakes, goes out in the night seeking a ‘light’ and is drawn through the needle’s eye. A dream of a dream, he returns to a bed less empty than before.” —Kenneth Anger

PSYCHE

Gregory Markopoulos, 1947-48, colour, sound, 25 min

“Psyche has no parallel among early American avant-garde films. Markopoulos was at once the filmmaker of his generation most attracted to narrative (he has adapted several literary works to film) and one of the most radical filmmakers in the world. He took such extreme liberties with Pierre Loüys’ unfinished novella that one would hardly recognise it as the source of his film. Nevertheless, he took just enough to give his film a cohesion and a tension that make it a continually fascinating work. Three interrelated characteristics define Markopoulos’ style: colour, rhythm, and atemporal construction.” —P. Adams Sitney, Visionary Film

Back to top

Date: 19 June 2003 | Season: California Sound/California Image

CALIFORNIA CONSCIOUSNESS

Thursday 19 June 2003, at 7pm

London Barbican Screen

The California Dream became a psychedelic hallucination when eastern mysticism fused with drug-fuelled fantasy in the heady 60s & 70s. Transcend trance end.

James Whitney, Lapis, 1963-66, colour, sound, 10 min

Scott Bartlett, 1970, 1972, colour, sound, 29 min

James Broughton, This is it, 1971, colour, sound, 9 min

Jordan Belson, Re-Entry, 1964, colour, sound, 6 min

Pat O’Neill, 7362, 1965-67, colour, sound, 10 min

Gunvor Nelson, Take Off, 1972, b/w, sound, 10 min

Charles I. Levine, Apropo of San Francisco, 1968, colour, sound, 4 min

PROGRAMME NOTES

CALIFORNIA CONSCIOUSNESS

Thursday 19 June 2003, at 7pm

London Barbican Screen

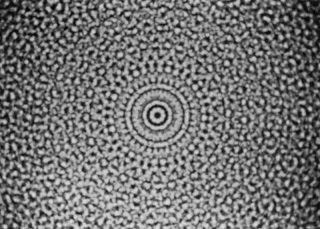

LAPIS

James Whitney, 1963-66, colour, sound, 10 min

“Lapis was as close as I could come at the time of conceiving a totally balanced opposition of stasis and flow, holding the paradox symbolically through wave and particle, pointing to a still centre of emptiness. Both in stasis and time, Lapis conforms to the circular form of the mandala. Only at the end is there an off-centre parting of two central black-eyed forms, which allow an emptiness to pass through and return to the beginning image.” —James Whitney

1970

Scott Bartlett, 1972, colour, sound, 29 min

“1970 – the year of the moon shot; the year of the Bartlett’s only son, Adam; the year Scott’s life peaked in high harmony and discord with the American culture. This autobiographical film presented so thorough a summation of Bartlett’s personal work that it rendered him harmless for years to come.” —Canyon Cinema catalogue

THIS IS IT

James Broughton, 1971, colour, sound, 9 min

“James Broughton’s creation myth, This Is It, places a 2-year-old Adam and a bright apple-red balloon in a backyard garden of Eden, and works a small miracle of the ordinary. And since that miracle is what his film is about, he achieves a kind of casual perfection in matching means and ends.” —Robert Greenspun, The New York Times

RE-ENTRY

Jordan Belson, 1964, colour, sound, 6 min

“When Belson gave up filmmaking in the early sixties, he diverted his creative energy to the practise of Hatha yoga. When the Ford Foundation offered him one of their coveted $10,000 grants in 1964, he turned them down. But after reconsidering, he accepted the money and re-entered filmmaking with Re-Entry, the first of his ‘personal’ films. For Belson the opposition of impersonal to personal art does not indicate an antithesis of geometrical formalism to Expressionism. As a yogi, Belson seeks the transcendence of the self. His personal cinema delineates the mechanics of transcendence in the rhetoric of abstraction.” —P. Adams Sitney, Visionary Film

7362

Pat O’Neill, 1965-67, colour, sound, 10 min

“This is film as art in pure presentational form. Patrick O’Neill has utilised colour, sound and images in a symphonic mode, attacking the consciousness with unusual power. 7362 does not say anything, but simply is, in the way that a kaleidoscope is the shapes, images and colours presented to the eye. Groups who want to break away from seeing cinema as stories and morals will find this a stirring introduction to the real possibilities of the form.” —Christian Advocate

TAKE OFF

Gunvor Nelson, 1972, b/w, sound, 10 min

“For contemporary audiences, particularly student audiences, Take Off is confrontational on several levels simultaneously. First, the apparent over-exploitation of the ‘male gaze’ during much of the film seems particularly outré in a 1990s classroom (both for those who believe in the liberation of women’s bodies from male control and for those who are uncomfortable with nudity in film and in public), until the film’s final destination is clear, at which point we realise that the three women who collaborated on the film have raised the spectre of ‘the gaze’ only to dismantle it. Indeed, we recognise, once Ellion Ness has ‘taken it all off’, that her smiles at the camera are not the smiles of submission to male desire that we thought they were, but smiles of complicity with her two media-guerrilla collaborators and with all those watching who are aware of the implications of a dehumanising gaze. A second level of confrontation, which is at least as powerful now as it was in 1972, results from the decision to use a stripper who does not precisely conform to contemporary societal standards for beauty or eroticism.” —Scott MacDonald, A Critical Cinema 3

APROPO OF SAN FRANCISCO

Charles I. Levine, 1968, colour, sound, 4 min

“(After or for Jean Vigo) with Ben Van Meter. Sound recording by Bob Cowan. A study in visual rhythms and structure, using the same basic element repeated with variations.” —Charles I. Levine

Back to top