Date: 29 October 2005 | Season: London Film Festival 2005 | Tags: London Film Festival

LITERARY LANDSCAPES

Saturday 29 October 2005, at 4pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

David Gatten, The Great Art of Knowing, USA, 2004, 37 min

‘On either side of a Life find a Library before and an Auction after: consider these figures as the sites for a collection created for the purposes of division and dispersal. This chapter of my ongoing exploration of the Byrd library finds its name and shape within a single volume from that collection: Kircher’s 17th century encyclopaedia. Herein find tangled texts and crossed destinies, filled with figures at once buried deep and tossed high by History, lined with traces of a forbidden romance. Love finds purchase between tightly shelved volumes.’ (DG)

Matthew Noel-Tod, Nausea, UK, 2005, 60 min

Nausea is a synthesis of text and image that draws inspiration from Impressionism, On Kawara, Barnett Newman and the existential diary by Jean-Paul Sartre from which it adopts its title. The video footage is a journal of observations shot entirely on a mobile phone. Crudely low resolution, it retains a fuzzy warmth and familiarity rather than the cold, impersonal qualities of much digital technology, challenging a ‘certain end-point in cinema, wherein we only ever imagine and receive mediated images.’ (MNT)

PROGRAMME NOTES

LITERARY LANDSCAPES

Saturday 29 October 2005, at 4pm

London National Film Theatre NFT3

THE GREAT ART OF KNOWING

David Gatten, USA, 2004, 16mm, b/w, silent, 37 min

On either side of a Life find a Library before and an Auction after: consider these figures as the sites for a collection created for the purposes of division and dispersal. The journey this time moves from the first light at dawn to the last rays of a sunset, reflected and refracted. In between find dry Fall turn toward the shadows of Spring and the stillness of death sparked by the singularities of a transcendental field. Find yourself resting uneasily half way up the stairs: Something has left the body, yet the body remains: what has left is on its way Elsewhere but cannot help but look back: this look animates the world and makes possible this Theory of Flight in the form of a bibliography. From Leonardo da Vinci to Jules-Etienne Marey practitioners of a certain mode of transcendental empiricism turned repeatedly to combinations of words and images describing the flight of birds.

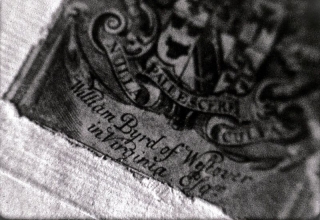

In 1726 William Byrd returned to Westover in Virginia and began construction of a garden soon to be called “the finest in the country, filled with the charming colours of the Humming Bird.” In a parallel pursuit, he collected the largest library in the colonies to serve as mirror for his mind and testament to his knowledge. Evelyn Byrd was fond of sketching the birds in the garden. Her interest was more than aesthetic and scientific; she devised a very different use for her father’s vast library. This chapter of my ongoing exploration of the Byrd library finds its name and shape within a single volume from that collection: Athanasius Kircher’s 17th century encyclopaedia, ‘The Great Art of Knowing’. Herein find tangled texts and crossed destinies, filled with figures at once buried deep and tossed high by History, lined with traces of a forbidden romance. Love finds purchase between tightly shelved volumes. In the spaces between the letters. In the lines themselves. An antinomian cinema seems possible. A gentle iconoclasm? The image is always backwards in a mirror. The story unfolds slowly.

Part IV of the Byrd project. (David Gatten)

NAUSEA

Matthew Noel-Tod, UK, 2005, video, colour, sound, 53 min

Existentialism is present in so many developments in 20th Century Art History and Sartre’s debts lie as much with Cezanne and Van Gogh as with Descartes and Heidegger. The whole text of Sartre’s book ‘Nausea’, at a speed of one word per frame, lasts for 53:37 minutes, so I used this duration as a base for editing. The text was then cut up and ordered randomly – missing every other word, backwards, etc, so that what is seen is literally just ‘words’, not Sartre’s words. The text is sometimes slowed down and edited to suggest a narrative, drawing unique relationships between word and image. In 2004, I started using a mobile phone video camera to record daily images. Like early cinematograph-style inventions, this technology’s legacy seems destined be through the very simple recording of people and their backgrounds. I thought it could support an attempt to record footage that was free from mediation, which was instinctive and free from analysis and artifice, and I recorded my life for roughly a year. The variability of the video frame rate and image compression became mostly predictable, but still surprised me with unpredictable rendering of one image or another. The most constant of these artefacts was the camera’s inability to register extreme areas of light, mostly apparent when filming the sun. These areas appeared black. Many things didn’t record ‘well’, such as people and movement. Other things took on a magical, painterly aura when filmed with the phone camera – skies, landscapes, still lifes. The pure colour sections are enlargements of certain clips to the scale of one pixel filling the screen. Other ‘abstract’ images, which appear like camera-less process driven distortion, are in fact the limitation of the camera to record certain images, notably ‘nothing’. Echoing the ideas of phenomenological discovery, reflexive consciousness and modernist redemption through art which inspired this video, the often casual nature of the images in Nausea comes ultimately from an examination of a certain ‘end-point’ in cinema, wherein we only ever imagine and receive mediated images – images of images. Is creative instinct in filmmaking purely an extension of this mediated post-modern situation? A failed romantic, moribund and nostalgic ideal? Or a valid area for self-examination and analysis of aesthetics? (Matthew Noel-Tod)

Back to top