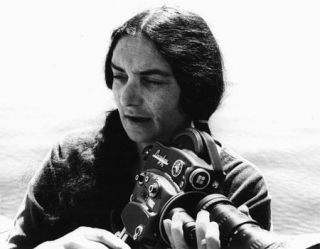

As one of the instigators of Canyon Cinema, Chick Strand (1931-2009) was at the heart of 1960s West Coast avant-garde. Her body of work, comprising of found footage and personally photographed material, has an astounding strength and vitality. Strand’s camera is almost continually in motion, catching details in kinetic close-up to convey celebrations of intimacy and the joys of living.

‘For most of her filmmaking career, the integrity of Strand’s vision lay aslant of prevailing fashions, so that only belatedly did the full significance of her radically pioneering work in ethnographic, documentary, feminist, and compilation filmmaking – and above all, in the innovation of a unique film language created across these modes – become clear. Though feminism and other currents of her times are woven through her films and though her powerful teaching presence sustained the ideals of underground film in several film schools in Los Angeles, hers was essentially a school of one.’ (David James, The Most Typical Avant-Garde)

INTIMATE VISION: FILMS BY CHICK STRAND 1

Thursday 15 November 2012, at 8pm

Barcelona Xcèntric CCCB

CARTOON LE MOUSSE

Chick Strand, USA, 1979, 15 min

In her collage films, Strand uses the magic of editing to conjure surreal humour from the connections between disparate fragments.

MOSORI MONIKA

Chick Strand, USA, 1970, 20 min

The impact of American missionaries on the Warao Indians in Venezuela is considered from the viewpoints of women from each side.

ANGEL BLUE SWEET WINGS

Chick Strand, USA, 1966, 3 min

A multi-layered cine-poem apropos life and vision.

LOOSE ENDS

Chick Strand, USA, 1979, 25 min

Found footage is used to convey the effect of information overload, finding wit and pathos in the complicated synthesis of personal experience and media assault.

ARTIFICIAL PARADISE

Chick Strand, USA, 1986, 13 min

‘The anthropologist’s most human desire: the ultimate contact with the informant. The denial of intellectualism and the acceptance of the romantic heart, and a soul without innocence.’ (CS)

KRISTALLNACHT

Chick Strand, USA, 1979, 7 min

‘Dedicated to the memory of Anne Frank, and the tenacity of the human spirit.’ (CS)

Chick Strand: I had a Degree in Anthropology and I was going to San Francisco State University to get my MFA and then my PhD and I thought, “Oh man, I’m 30 fucking years old and now I’ve got two kids … I don’t want to listen to these old farts ever again!” So I came down to Los Angeles to go to film school at UCLA.

UCLA is where I met Pat O’Neill, he was a student in the Art Department and I was in the Film Department, but we came together over photography because I thought that if I took photography then I’d learn more about film – the physics of it, how you do it, how you can manipulate it. We were down the dark rooms with a wonderful teacher there called Robert Heineken, he was pretty well known, who somehow had got a 16mm contact printer. Pat O’Neill was the only one using it, and he showed me what he knew and then I was using it. It was quite wonderful. We had to develop our films in regular trays and stuff like that. I was pretty good. Pretty hard to keep our butts out of the soup there but it was really rather fun.

MW: And so was this how you made Kulu Se Mama and those early abstract films?

CS: It was. Kulu Se Mama was an independent course that I did using special effects, my first attempt really. I was interested first of all in photography and Bob Heineken turned us onto solarisation. There was a photographer named Edmund Teske who was really involved in that. I think maybe Pat had made 7362 by then and maybe we talked about it. So I was pretty much playing with solarisation and was sort of entranced by the natural colour that came out. Rather than putting colour in I was really entranced by these bronzes and coppers. I found out too that if you made the soup thick, just sort of let it sit there and gel, then you could get these marvellous greens and I thought, “Oh, that’s what I want to do,” … but then I got into the ethnographic thing and got sent to Venezuela, to the jungles of the Orinoco. So what was a girl to do but just do an ethnographic film?

I went there with the idea in mind that Mosori Monika was going to be an ethnographic film, using that methodology more or less. I never believed that an ethnographic film would ever take the place of the written word, but that it would sort of introduce people who’d watch the films and then studied the culture to actual seeing the people move around, you know? I was so sick of the black and white photographs of guys with spears and all that stuff … But you cannot be objective, totally objective, I couldn’t help myself juxtaposing what was actually being said by an Indian woman – translated – over a picture, over an image …

Even though I shoot documentary style, it isn’t, because I don’t set out to do that and I don’t weigh it out in any certain way, although I’m so nosey – “Tell me about your life?” – but I couldn’t understand this Warao Indian woman I was filming one bit. There was a guy who spoke Spanish and English that was part of the trio of us that went down to Venezuela, totally paid for by UCLA, then he had a translator that spoke Spanish and the Indian language, and then there was the Indian woman. I said, “Tell me about your life,” and then he left her talking for about 20 minutes. I’d say, “Jorge, is she telling about the life?” and he asked and the guy says, “Yeah, yeah!” I had no idea what she was talking about, no idea at all, but we translated it immediately so I could somehow get some images that went along with it. Of course it’s a lie because if she’s talking about when she was young you can’t really show it, you have to be symbolic about it in a way.

Margaret Mead hated it. The Flaherty Seminar was going on and she was still alive, and it was just at that time when I was seeing ethnographic films a lot. That was very interesting because one of the things that sort of influenced me to be a little more humane about what I was doing, a little more digging in, was her film called Trance and Dance in Bali, where the guys are flaying themselves. You never got the feeling of what it was like to be one of those guys, never, it was just like going to the zoo … It was absolutely wonderful that these people went out there with cameras and filmed all this stuff and tried to preserve the cultures, at least on paper and then film, it was really remarkable. In a sense, that film and many others like Nanook of the North influenced me with ethnography and all my work.

Then I went to Mexico and I was so entranced with the colour and the feeling we got there, and how mysterious it was, like true-life surrealism. You’d go into a church and they’ve got Jesus in a glass case, bleeding all over, and on the walls they’ve got relics that are supposed to be the skin of saints or something like that. Or you sit in your patio and down the street you hear the donkey braying and ducks quacking and then you go out the door and up the street there’s some guy playing a flute and drum. It’s crazy and it really is wonderful. Mexico to me was a very magic place.

MW: Artificial Paradise is one of your Mexican films.

CS: For some complicated reason, I met this young man who was a groom at a horse ranch outside of town and I really fell in love with him, like when you get crushes on people but you never follow through or anything. It was just this young guy, couldn’t speak English, totally uneducated, so I taught him how to drive a car and how to read. He was quite beautiful to me. I thought that every movement was sort of his art, and the way he saw things and the poetry he’d write, the songs he’d sing. Not only that but he was completely captivated, not by me so much as just the adventures we could have together. “Come on …”, in my lousy Spanish, “I want to film you in the lake because of these pink flowers here.” So we’d go in the water and then I realised, “God, it’s smelly, it’s probably where the sewer came out!” but he didn’t say anything. He had this big crush on my friend Lee and I just had to make a romantic film about it, it had to be about Sappho thinking of men instead of women. That’s the way it was really, the boy across the river whose skin is like peaches but I cannot swim. Of course in the end she swims – have your cake and eat it too! I really love movement close in. We never see it because we’re never that close. Instead of special effects and all that stuff, I could just use the camera itself, and move with the camera and let everything unfold. That’s what Artificial Paradise is about, aside from this romance that wasn’t a romance. I always thought of films as poems, they’re poetic, but anyway that’s old-fashioned!

MW: At a certain point you were making the Mexican films and found footage films like Loose Ends in parallel. What was your interest in making collage films?

CS: The footage was available, and certainly after Bruce Conner’s example I thought, “Oh, that’s a possibility.” I used to make cut-out collages with stuff from magazines, but when I saw A Movie, that really blew me away. While I was teaching I somehow got my hands on a whole bunch of old black and white footage from the educational department, and maybe I stole a little bit of footage from Dream of Wild Horses and stuff like that, and I just did it. The thing that I love about found footage is you have to make something out of nothing in a sense. You have all these disparate pieces that can be connected or re-connected or woven and re-woven and you make the choices and it becomes a very personal thing.

The secretary of my department, her father had all this stuff that showed his children during the war. And there were educational films in the Occidental College Library which I just absconded with, I mean they didn’t want them anymore, it was quite wonderful. Then of course there was the L.A. Public Library and, you know, I just would have dupes made. I had a student whose father owned a big special effects place. I could take my black and white footage there and he would wet gate print it and make a master so that a lot of the scratches would be gone. I can’t believe I did that, but I’d do it again! When I started, I’d shoot my own stuff but still I sort of see it as a collage because I don’t know what I’m shooting, I had no idea, and most the time I don’t have control over the people because they give me a present of themselves. “Give me the gift of yourself, tell me your life story!”

These excerpts are from an interview with Chick Strand conducted on 15 March 2008 for the forthcoming book “Critical Mass: An Oral History of Avant-Garde Film, The New American Cinema and Beyond”. Initial research for this project was funded by the British Academy.

Back to top