British filmmakers led a drive beyond the screen and the theatre, and their innovations in expanded cinema inevitably took the work into galleries. After questioning the role of the spectator, they began to examine the light beam, its volume and presence in the room.

Screening introduced by William Raban and Anthony McCall.

EXPANDED CINEMA

Friday 3 May 2002, at 7:30pm

London Tate Modern Level 7 East

CASTLE ONE

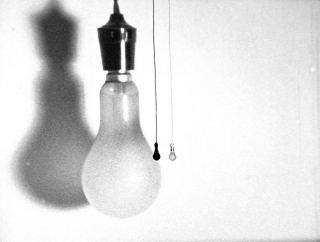

Malcolm Le Grice, 1966, b/w, sound, 20 min

“The light bulb was a Brechtian device to make the spectator aware of himself. I don’t like to think of an audience in the mass, but of the individual observer and his behaviour. What he goes through while he watches is what the film is about. I’m interested in the way the individual constructs variety from his perceptual intake.” —Malcolm Le Grice, Films and Filming, February 1971

“… totally Kafkaesque, but also filmically completely different from anyone else because of the rawness. The Americans are always talking about ‘rawness’, but it’s never raw. When the English talk about ‘raw’, they don’t just talk about it, it really is raw – it’s grey, it’s rainy, it’s grainy, you can hardly see what’s there. The material really is there at the same time as the image. With the Germans, it’s a high-class image of material, optically reproduced and glossy. The Americans are half-way there, but the English stuff looked like it really was home-made, artisanal, and yet amazingly structured. And I certainly thought Castle One was the most powerful film I’d seen, ever…” —Peter Gidal, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

“Malcolm said to me “Ideally in this film there should be a real light bulb hanging next to the screen, but that’s not possible.” And I said “It’s not possible to hang a light bulb?” He said “Well, I don’t see how we could possibly do this.” I said “Well the only question is how do we turn it on and off at the right moments? … Are you able to do that as a live performance?” He looked at me like the world was going to end! And I said “The switch will be there.”” —Jack Moore, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

TAKE MEASURE

William Raban, 1973, colour, silent, 2 min

“The thing that strikes me going into a cinema, because it is such a strange space and it’s organized to allow you to get enveloped by the whole illusion of film, when you try and think of it in terms of real dimensions it becomes very difficult. The idea of a sixty foot throw or a hundred foot throw from the projector to the screen just doesn’t enter into the equation. So I thought the idea of making a piece that made that distance between the projector and the screen more tangible was quite an interesting thing to do.” —William Raban, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

“Take Measure is usually the shortest of my films, measuring in feet that intangible space separating screen from projector box (which is counted on the screen by the image of a film synchronizer). Instead of being fed into the projector from a reel, the film is strung between projector and screen. When the film starts, the film snakes backwards through the audience as it is consumed by the projector.” —William Raban, Perspectives on British Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1977

DIAGONAL

William Raban, 1973, colour, sound, 6 min

“Diagonal is a film for three projectors, though the diagonally arranged projector beams need not be contained within a single flat screen area. This film works well in a conventional film theatre when the top left screen spills over the ceiling and the bottom right projects down over the audience. It is the same image on all three projectors, a double-exposed flickering rectangle of the projector gate sliding diagonally into and out of frame. Focus is on the projector shutter, hence the flicker. This film is ‘about’ the projector gate, the plane where the film frame is caught by the projected light beam.” —William Raban, Perspectives on British Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1977

“The first great excitement is finding the idea, making its acquaintance, and courting it through the elaborate ritual of film production. The second excitement is the moment of projection when the film becomes real and can be shared with the audience. The former enjoyment is unique and privileged; the second is not, and so long as the film exists, it is infinitely repeatable.” —William Raban, Arts Council Film-Makers on Tour catalogue, 1980

HAND GRENADE

Gill Eatherley, 1971, colour, sound, 8 min

“Although the word ‘expanded’ cinema has also been used for the open/gallery size/multi screen presentation of film, this ‘expansion’ (could still but) has not yet proved satisfactory – for my own work anyway. Whether you are dealing with a single postcard size screen or six ten-foot screens, the problems are basically the same – to try to establish a more positively dialectical relationship with the audience. I am concerned (like many others) with this balance between the audience and the film – and the noetic problems involved.” —Gill Eatherley, 2nd International Avant-Garde Film Festival programme notes, 1973

“Malcolm Le Grice helped me with Hand Grenade. First of all I did these stills, the chairs traced with light. And then I wanted it to all move, to be in motion, so we started to use 16mm. We shot only a hundred feet on black and white. It took ages, actually, because it’s frame by frame. We shot it in pitch dark, and then we took it to the Co-op and spent ages printing it all out on the printer there. This is how I first got involved with the Co-op.” —Gill Eatherley, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

LIGHT MUSIC

Lis Rhodes, 1975-77, b/w, sound, 20 min

“Lis Rhodes has conducted a thorough investigation into the relationship between the shapes and rhythms of lines and their tonality when printed as sound. Her work Light Music is in a series of ‘moveable sections’. The film does not have a rigid pattern of sequences, and the final length is variable, within one-hour duration. The imagery is restricted to lines of horizontal bars across the screen: there is variety in the spacing (frequency), their thickness (amplitude), and their colour and density (tone). One section was filmed from a video monitor that produced line patterns on the screen that varied according to sound signals generated by an oscillator; so initially it is the sound which produces the image. Taking this filmed material to the printing stage, the same lines that produced the picture are printed onto the optical soundtrack edge of the film: the picture thus produces the sound. Other material was shot from a rostrum camera filming black and white grids, and here again at the printing stage, the picture is printed onto the film soundtrack. Sometimes the picture ‘zooms’ in on the grid, so that you actually ‘hear’ the zoom, or more precisely, you hear an aural equivalent to the screen image. This equivalence cannot be perfect, because the soundtrack reproduces the frame lines that you don’t see, and the film passes at even speed over the projector sound scanner, but intermittently through the picture gate. Lis Rhodes avoids rigid scoring procedures for scripting her films. This work may be experienced (and was perhaps conceived) as having a musical form, but the process of composition depends on various chance operations, and upon the intervention of the filmmaker upon the film and film machinery. This is consistent with the presentation where the film does not crystallize into one finished form. This is a strong work, possessing infinite variety within a tightly controlled framework.” —William Raban, Perspectives on British Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1977

“The film is not complete as a totality; it could well be different and still achieve its purpose of exploring the possibilities of optical sound. It is as much about sound as it is about image; their relationship is necessarily dependent as the optical soundtrack ‘makes’ the music. It is the machinery itself which imposes this relationship. The image throughout is composed of straight lines. It need not have been.” —Lis Rhodes, A Perspective on English Avant-Garde Film catalogue, 1978

LINE DESCRIBING A CONE

Anthony McCall, 1973, b/w, silent, 30 min

“Once I started really working with film and feeling I was making films, making works of media, it seemed to me a completely natural thing to come back and back and back, to come more away from a pro-filmic event and into the process of filmmaking itself. And at the time it all boiled down to some very simple questions. In my case, and perhaps in others, the question being something like “What would a film be if it was only a film?” Carolee Schneemann and I sailed on the SS Canberra from Southampton to New York in January 1973, and when we embarked, all I had was that question. When I disembarked I already had the plan for Line Describing a Cone fully-fledged in my notebook. You could say it was a mid-Atlantic film! It’s been the story of my life ever since, of course, where I’m located, where my interests are, that business of “Am I English or am I American?” So that was when I conceived Line Describing a Cone and then I made it in the months that followed.” —Anthony McCall, interview with Mark Webber, 2001

“One important strategy of expanded cinema radically alters the spatial discreteness of the audience vis-à-vis the screen and the projector by manipulating the projection facilities in a manner which elevates their role to that of the performance itself, subordinating or eliminating the role of the artist as performer. The films of Anthony McCall are the best illustration of this tendency. In Line Describing a Cone, the conventional primacy of the screen is completely abandoned in favour of the primacy of the projection event. According to McCall, a screen is not even mandatory: The audience is expected to move up and down, in and out of the beam – this film cannot be fully experienced by a stationary spectator. This means that the film demands a multi-perspectival viewing situation, as opposed to the single-image/single-perspective format of conventional films or the multi-image/single-perspective format of much expanded cinema. The shift of image as a function of shift of perspective is the operative principle of the film. External content is eliminated, and the entire film consists of the controlled line of light emanating from the projector; the act of appreciating the film – i.e., ‘the process of its realisation’ – is the content.” —Deke Dusinberre, “On Expanding Cinema”, Studio International, November/December 1975

Back to top