Floating Through Time: The Films of Larry Jordan

Date: 4 May 2001 | Season: Larry Jordan | Tags: Oberhausen Film Festival

FLOATING THROUGH TIME: THE FILMS OF LARRY JORDAN

4 & 5 May 2001

Oberhausen Lichtburg Filmpalast

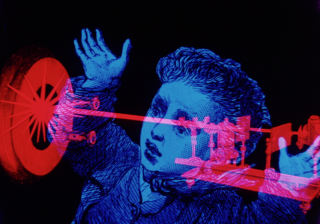

Cinematic Duplicity: The Twin Worlds of Larry Jordan

Whether concerned with reality or the unconscious world, each work by Larry Jordan is a small wonder, a unique excursion both outwards and within. Although best known for his fragile animations, he has continued to work with live photography throughout his life. In his animations, images are liberated of their intrinsic meanings allowing the viewer to derive their own interpretation as the filmmaker travels along his inner journey. By contrast, Jordan’s live action cinematography frequently captures a direct sense of place, retaining a connection to the world at large. Presenting raw, untreated footage, he documents the essence of his world. All of his work conveys a sense of exploration and self-discovery, an aspiration to higher things. Images may be inspired by dream visions, or arise from a state of complete openness. Often working in an extemporised manner, by embracing chance and fortune, Jordan is free to wander through an infinite range of possibilities.

“Animation is, I guess you’d say, my interior world, and the live films are pretty much my interface with the real world. I may use some quick cutting, but I don’t use a lot of optical printing or manipulation of the image. I like to see the raw image from the real world, that excites me on the screen more than a manipulated image. Even in animation, I like to see flat-out what’s there in front of the camera, and see if the bold un-art-ised image can’t be the strongest thing. I used to feel I had to get out of there and work with people in the world, to keep that connection going. I couldn’t just stay in the studio and do animation all the time, so I’d go out to try to capture ‘spirit of place’. The world is miraculous, but people working in film don’t feel that’s enough, I guess, not exciting enough to an audience. I’ve tried to find ways of putting the real world, the way it really is, into the live films at some level.”

Jordan’s interest in film began while studying literature at Harvard. He attended the university’s film series, seeing Cocteau, Clair and Eisenstein, as his high school friend Stan Brakhage was beginning his own serious investigation of the medium. Jordan realised that his interest was more with the image than the word, and on returning to Denver he began working the tradition of the avant-garde trance film. Moving to San Francisco, he became involved in a creative group that included Robert Duncan, Jess Collins, Philip Lamantia, Kenneth Rexroth and Michael McClure. Inspired by this artistic milieu of poets and artists working outside the mainstream, Jordan shot Visions of A City, a portrait of a place and that of a friend, combining trance vision with a sense of alienation.

“The city is hard and impersonal, hence, the reflected image. The man emerges out of this, is there for a little while, and then is absorbed back under the hard surface of the city. What’s really important to me is that it’s a little glimpse of San Francisco in ’57 – it’s hard to find that anywhere. It’s also a portrait of Michael McClure in 1957, the only one that moves. Film has done very badly at documenting the world as it really is, whereas still photography has done very well. So much energy in film has gone into the mental construct, the script, the drama, the fairytale; so what have you got that’s a time machine ? You’ve got Man with a Movie Camera, Berlin, Symphony of a City and a few films of New York.”

For many years a 15-minute silent version existed, and was occasionally shown as a background at poetry readings. Jordan always felt the film was not particularly tight and in 1978 he returned to the footage to reshape it. By condensing the film and adding a meditative raga soundtrack by Bill Moraldo, he built a freewheeling, but concise city symphony. At this time in the late 1970s, Jordan also assembled Cornell 1965, an evocative document of the artist whom the filmmaker considers his mentor. After meeting in 1955, Jordan corresponded with Joseph Cornell for 10 years. He occasionally did photographic assignments for him, and eventually moved to New York to help with box construction and film editing.

“With Cornell, I learned a lot about box making; I didn’t learn about filmmaking, and I don’t collage the way he collages. I tend to work in a concentrated manner. I don’t have the same sensibility as Max Ernst or Jess, and feel closer to Cornell, in that there’s no aggressive agenda like with the Surrealists.”

Max Ernst is the other most obvious visual inspiration in the development of Jordan’s techniques, directly influencing his eventual style of animation. The early collage films used a moving camera tracking over a still image, until a moment of enlightenment set him in a new artistic direction.

“In the very early 60s, you couldn’t just go to the bookstore and find an edition of Max Ernst collage novels, but my friend Jess had both of them. He loaned them to me and I loved them so much that I photographed each one – page after page after page. I was putting the negatives in the enlarger and the images would come up in the solution one after another. All of a sudden I realised that I was, in a way, watching a movie in very, very slow motion. By that time I knew enough about film to know how you could single frame things and I thought “I could go out and find engravings and cut them up and make them move !”. It hit me that if you cut up engravings they would have that very photogenic look because there is no half tone there, just white background and black lines, which photographs very well. There would be the surreal element of disparate images coming together and there would be a casting back to another time with that material, it seemed to make sense.”

Aside from the optical aspects of his vision, aural inspiration plays a direct role in the creative process. Jordan has often spoken of filmmaking in musical terms, comparing his approach with that of a composer, and believing that the essential focus in both arts is timing.

“It’s the internal timing that makes all the difference. I’ve a very strong feeling that whether you’re talking about a documentary or a drama, you can get away with some faultiness in almost any area, in sound, colour, or movement, but films that don’t have good timing don’t work, no matter what genre. The best films are the ones that handle the temporal element the best. I’ve been lucky – I’m not a musician, I don’t read or play music, but I feel very strongly that films are a kind of visual music in the sense that the farther I went with animation, the more I realised that my problems aesthetically were the same as the composer’s, centred mostly around the timing. So long as I just kept feeling like I was playing some kind of visual, musical composition, then things would go down the way they should go down. If I tried to force something to be long or slow then it felt superficial or stilted but if I just kept a fine, light tension like playing music then I was okay.”

The use of music in Jordan’s films is incredibly sensitive. Given his impeccable choice of accompaniment, it’s not surprising that he sees his role as an animator being similar to that of a composer. To complement his strong sense of intuition over soundtracks, a certain amount of synchronicity contributes to the marriage of sound and image, and the correct piece of music often arise in a completely spontaneous and unexplainable manner. The soundtrack for Hamfat Asar was a cut from an LP that was purchased on impulse from a discount record bin. One track was found to run exactly the length of the film, even dividing up into 3 movements to match the visual continuity. Duo Concertantes won first prize at the Ann Arbor Film Festival as a silent film and existed as such for 2 years until Jordan turned on a radio during a coffee-house screening in San Francisco. The broadcast was found to fit the film perfectly. After calling the station to find out what it was, he tracked down the sonata by little-known 18th century composer Giovanni Battista Viotti, which has played with the film ever since.

“The process is usually different on each film, whether it’s mystical, or synchronistic. I have something that I say, though I don’t know how exact it is, but if I can feel that I have been working on the film in the same spiritual vein as the composer of the music, then I can put the two together. Whether that’s what it is I don’t really know, but it’s really intuitive. Sometimes I go directly to a piece of music and it’s the first thing I think of, but often I go through a lot of things and eliminate. That’s the way the animation has always worked as well, I eliminate nine things out of ten, and one thing is right for the film.”

For Postcard from San Miguel, his most recent cine-poem, the music was present throughout the filmmaking process. After hearing a performance of “Pavane” by Gabriel Fauré shortly before travelling to Mexico, Jordan took along a cassette, listening to it on a Walkman while shooting to make the pace of filming match the flow of the music.

While many of the live action films seek to capture the pictorial essence of a particular location, it is the mood that becomes the over-riding theme of The Old House, Passing. Deciding to make a ‘ghost film’, Jordan and 3 friends read classical supernatural literature to get into the correct frame of mind. Their discussions were recorded and subsequently used to plan the shoot, which took place in an archetypal haunted house. Though he used out-dated stock, Jordan was surprised to find that the footage he got back from the lab was extremely dark. Being initially disappointed with the result, the film was left unedited for a year.

“After seeing the main character, John Graham, in a film by Ben Van Meter, I got inspired about the project. I remember sitting down in my studio one day and without looking at the footage I thought I’d write down a stream of consciousness list of images from memory. Then I cut the film that way, and not only did it work, but I’d listed all the images that were good, and none that weren’t good. It originally had a straight-line narrative, but now it’s completely elliptically cut. You can’t see a story directly, but it’s there floating around you all the time. I’ve since used that form of cutting on about six other films. I consider it a surreal game of free association, not to be played if there are going to be any interruptions or any equivocation.”

Jordan’s style of animation reached its pinnacle in the 1980s, when he realised two remarkable works. Sophie’s Place is an 86-minute, in-camera edited improvisation that took 7 years to complete. He regards the film as an “alchemical autobiography”, in which unfixed images intimate ancient Greek or Gnostic spiritual wisdom. Stan Brakhage has referred to it as “the greatest epic animation film ever”. Jordan followed up with The Visible Compendium, reaching further out, simultaneously travelling in many different directions. It’s the culmination of everything he has learned as an animator, a carefully constructed sequence of disparate scenes assembled to a sound collage of collected scraps of audio.

“I’m not a scholar, but I have read and absorbed, I think deeply, a lot of the major world religions. For many years I was intensely into Buddhist Tibetan beliefs. I had a classical education and I studied Latin for many years and the ancient world came alive to me. Religion, so long as it’s not formal, is very potent for me. My feeling is that all these things buzz around in my head and get into the films, but if I try to do anything consciously, like make a scene that represents something from the “Bhagavad-gita” or something – forget it, it just looks awful. I have to stay away from meanings for the symbols.”

A vivid sense of the spiritual world emerges from the animated films. It’s a common misconception that Jordan works as a cinematic magician, like Kenneth Anger or Harry Smith, using a system of pre-defined codes to communicate his ideas. He’s keen to make a distinction, claiming that he is an alchemist working without a codified system. It is important to be aware that the filmmaker no more knows the meaning of the symbols he uses than does the viewer.

“I do believe in an underworld, a classical underworld. I think Jung would call it ‘the collective unconscious’, where if I open the door, the images that we all recognise will come out. If there’s any seeming meaning that appears to you, while the film is on the screen, that’s what it means and it will be different for everybody. I don’t want the animation films to be like most film work, which is a reference to something that has been photographed in the past. I want the films only to exist while they’re on the screen and not refer to anything in the past. It’s a Rorschach, in other words. A symbol is not a metaphor. Those are two separate words and two entirely different meanings. A circle is a symbol and you could write ten books about a circle and you’d never come to the end of the meaning. A symbol, by definition, is not definable.

“Some people ask questions after the screenings, that always centre around the idea that I have a secret language of symbols, that I know what they mean and the audience doesn’t. I have to explain that I don’t know the meaning of them any more than the meaning of my dreams.”

By resisting obvious definition, and by continuing the dualistic approach of interior animation and exterior photography, Jordan has been able to build a considerable catalogue of human and spiritual experience. In allowing everyone to decipher the images in an individual way, he is able to speak to all of all us through his extraordinarily personal films.

Mark Webber

Based on a telephone interview with Larry Jordan, 13 March 2001. Thank you Larry Jordan, Joanna McClure, Milos Stelek, Dr. William Moritz and Alex Deck.