Minimal cinema with maximal effect. Few films provide the intense, stroboscopic viewing experience of The Flicker, a non-objective film composed only of opaque and clear frames, and a pulsing electronic soundtrack. Conrad’s cinematic debut still astounds audiences four decades after its creation, and will be screened together with other works exploring audio-visual harmonics and the radical production processes of cooked and electrocuted films.

The screening, introduced by Tony Conrad, will be followed by a reception to celebrate the publication of “Beyond the Dream Syndicate” (Zone Books/MIT).

TONY CONRAD: FLICKER AND PROCESS FILMS

Friday 13 June 2008, at 7pm

London Tate Modern

THE FLICKER

Tony Conrad, USA, 1966, 16mm, b/w, sound, 30 min

I think that The Flicker acts as a very versatile art object. The observer can really use it to his own means over a wide range of possibilities. The beauty lies within the beholder himself. In most aesthetic presentations – drama, cinema, music – the common attitude is that the amusement or the beauty or the effect of the experience is wholly within the entertainer; that the entertainer is actually creating the impressions or the reaction himself. The Flicker, I think, presents a clean-cut case of the experience lying within the observer. Most of the details, most of the impact, most of what people find it in, what they take away from having watched the film, wasn’t there, was conjured up only when they watched this film: it didn’t exist before, it doesn’t exist on film, it wasn’t on the screen.

CURRIED 7302

Tony Conrad, USA, 1973, 16mm, colour, silent, 2 min

Conrad began a series of ‘Cooked Films’ in 1973. Folding social and political concerns into the process in an explicit manner, Conrad – who at the time was serving as primary caregiver to his child, as well as professor of film at Antioch – adapted the practice of filmmaking to the stereotypically female role of domestic cook. Usually substituting ‘raw’ film in the place where different recipes called for onions, Conrad ‘processed’ the footage in various manners on his countertop or stove, with the result being, as Conrad recalled about Curried 7302 (1973), “this gorgeous mottled yellow, abstract thing.” (Branden Joseph

7302 CREOLE

Tony Conrad, USA, 1973, 16mm, colour, silent, 1 min

The second work in the series was a film chicken creole, the projection of which caused – through the thick alimentary residue still clinging to the celluloid – gate slipping and other effects simulated in structural films. “Well, this was very interesting because the meat ran all over the projector, and it was full of grease and chicken. It slipped in the gate, and it stunk because the lamp heated it up, and it was really like an olfactory experience, and it tested the skill of the projectionist, who is covered in slime …” (Branden Joseph

4-X ATTACK

Tony Conrad, USA, 1973, 16mm, b/w, silent, 2 min

Foregrounding the manner in which film could be ‘exposed’ and developed via heat, pressure, or electricity, rather than merely by light and developer fluid, Conrad produced a ‘material’ paracinema. In 4-X Attack, he struck a roll of celluloid with a hammer in a darkroom. “The material being brittle,” Conrad noted, “it was not only left with stress-bearing deformations, but was compressed in points, scraped and sheared in others, and generally speaking completely totalled.” Once the film was fractured into myriad pieces, Conrad swept them back together, “flashed the film once with a strobe, so as to activate the latent stress record,” developed it in a cheese cloth sack, and then painstakingly, even archeologically, reconstructed the roll (it is, afterall, an ‘edited’ film) into a projectable movie.” (Branden Joseph

FILM FEEDBACK

Tony Conrad, USA, 1974, 16mm, b/w, silent, 14 min

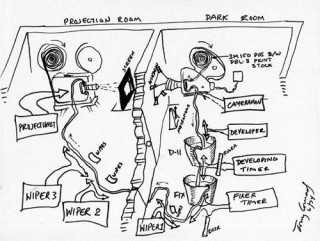

The cybernetics of video applied to film production. Film Feedback was produced in ‘real time’ by processing and projecting the film while it was being shot. Made with a film-feedback team which I directed at Antioch College. Negative image is shot from a small rear-projection screen, the film comes out of the camera continuously (in the dark room) and is immediately processed, dried, and projected on the screen by the team. What are the qualities of film that may be made visible through feedback?

ARTICULATION OF BOOLEAN ALGEBRA FOR FILM OPTICALS

Tony Conrad, USA, 1975, 16mm, b/w, sound, 75 min (10 min excerpt)

The work that served for me as a checkmate in the ‘structural’ film game is Articulation of Boolean Algebra for Film Opticals. This film achieved something of an apogee in formalist design, that conceptual regimentation which, in relation to de Sade’s eroticism, Barthes called “encyclopaedic […] the same inventorial spirit which animates Newton or Fourier.” (The Metaphor of the Eye, 1963.) Articulation literally unifies the optical and sound tracks. Both are the result of a design that follows an algorithmic system of stripes. The scale of the six stripes on the film strip positions them in relation to screen design, flicker, tone, rhythm, and meter, all with octave relationships.

THE EYE OF COUNT FLICKERSTEIN

Tony Conrad, USA, 1967/75, 16mm, b/w, silent, 7 min

The sustained dead gaze of black and white TV ‘snow’, captured in 1965 and twisted sideways, draws the viewer hypnotically into an abstract visual jungle.

STRAIGHT AND NARROW

Beverly & Tony Conrad, USA, 1970, 16mm, b/w, sound, 10 min

Straight and Narrow is a study of subjective colour and visual rhythm. Although it is printed on black and white film, the hypnotic pacing of the images will cause most viewers to experience a programmed gamut of hallucinatory colour effects. Through the intermediary of rhythm, the maximal impact is drawn from the simplest of universal human images: straight horizontal and vertical lines.

All texts or quotes by Tony Conrad unless otherwise noted. Texts by Branden Joseph have been adapted from “Beyond the Dream Syndicate: Tony Conrad and the Arts After Cage” (Zone Books / MIT Press).

Back to top