Seeing Sound: Lightning Strikes the Optic Nerve

Date: 17 October 2001 | Season: Cinema Auricular

SEEING SOUND: LIGHTNING STRIKES THE OPTIC NERVE

Wednesday 17 October 2001, at 7:30pm

London Barbican Cinema

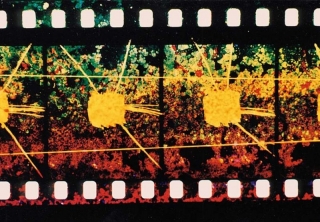

Optical sound on 16mm film – a lightbulb reads a strip of amorphous black emulsion on clear celluloid and it somehow makes sound sense. Since the 1930s artists have examined and exploited the possibilities of drawing or printing a soundtrack. Two senses combined and confounded, both musical and cacophonous. Can you see what you hear?

Oskar Fischinger, Ornament Sound, 1932, 7 min

Norman McLaren, Dots (Points), 1948, 3 min

Barry Spinello, Soundtrack, 1969, 10 min

Richard Reeves, Linear Dreams, 1997, 7 min

Pierre Rovere, Black and Light, 1974, 8 min

Lis Rhodes, Dresden Dynamo, 1974, 5 min

Chris Garrett, Exit Right, 1976, 3 min

Jun’ichi Okuyama, My Movie Melodies, 1980, 7 min

Guy Sherwin, Musical Stairs, 1977, 10 min

Peter Tscherkassky, L’Arrivée, 1998, 3 min

Taka Iimura, Shutter, 1971, 22 min

Screening introduced by filmmaker Guy Sherwin.

PROGRAMME NOTESSEEING SOUND: LIGHTNING STRIKES THE OPTIC NERVE

Wednesday 17 October 2001, at 7:30pm

London Barbican Cinema

ORNAMENT SOUND

Oskar Fischinger, Germany, 1932, b/w, sound, 7 min

‘You ear what you see, you see what you ear’. Indeed, on the left side of the image, unravelling vertically, is the synchronised drawing of the sound wave that is heard. Along the drawing of these sound waves moving small rectangles with appear each new sound level, indicating the height of the note produced in conventional notation, for example C#4 for ‘Do #’ in the fourth octave on the piano. Tönnende Ornamente thus presents the spectral range of the synthetic sound to us. At the beginning of film a falling scale explores the low register, followed by a perambulation of an octave in the acute part of the sound spectrum. Fischinger also presents the various stamps and types of attack which one can obtain with the optical sounds. (Philippe Langlois)

DOTS (POINTS)

Norman McLaren, Dots (Points), Canada, 1948, colour, sound, 3 min

This film of geometric abstractions drawn directly on the film with pen and ink was made independently by McLaren. Exploring the synchronisation of the visuals with a synthetic soundtrack, McLaren drew a percussive rhythm of clicking sounds along the edge of the film. The soundtrack reveals how early in his career McLaren achieved a sophistication in the use of this method. The music ranges over several octaves, integrating perfectly with the moving blue and white dots that flip across the screen on a red background. (Maynard Collins)

SOUNDTRACK

Barry Spinello, Soundtrack, USA, 1969, b/w & colour, sound, 10 min

John Cage wrote, in 1938, of a “new electronic music” to be developed out of the photoelectric cell optical-sound process used in films. Any image – his example is a picture of Beethoven – or mark on the soundtrack, successively repeated, will produce a distinct pitch and timbre. This new music, he said, would be built along the lines of film, with the basic unit if rhythm logically being the frame. However, with the subsequent development of magnetic tape a few years later (and the advantages it has in convenience, speed, capacity to record, erase and playback live sound), the filmic development of electronic music initially envisioned by Cage was obscured. Had magnetic record tape never been invented, undoubtedly a rich new music would have developed via optical sound means, and composers would have found ways to work with film.

LINEAR DREAMS

Richard Reeves, Canada, 1997, colour, sound, 7 min

In Linear Dreams, Richard Reeves explores new realms of the imagination. The piece begins with a line pulsing to a heartbeat -the base for all living things. Images then explode and implode until they are released from the human form, expand outward over a vast mountain range, and then return to their origin. Reeves’ hand-drawn soundtrack underscores Linear Dreams, creating a multiple award-winning piece filled with rhythmic electricity.

BLACK AND LIGHT

Pierre Rovere, Black and Light, France, 1974, b/w, sound, 8 min

This film was directly executed on computer without cinematographic intervention or equipment. It is not the communication of a movement, but a succession of facts made up that the device of projection translated for us into impressions of movements. This film does not refer to an external reality, but wants to be its own reality.

DRESDEN DYNAMO

Lis Rhodes, UK, 1974, colour, sound, 5 min

The result of experiments with the application of Letraset and Letratone onto clear film. It is essentially about how graphic images create their own sound by extending into that area of film which is ‘read’ by optical sound equipment. The final print has been achieved through three separate, consecutive printings from the original material, on a contact printer. Colour was added with filters on the final run. The film is not a sequential piece. It does not develop crescendos. It creates the illusion of spatial depth from essentially flat, graphic, raw material. (Tim Bruce)

EXIT RIGHT

Chris Garrett, Exit Right, UK, 1976, b/w, sound, 3 min

A one second shot of me walking into the shot wearing a striped jersey was printed repeatedly. This strip of negative was moved laterally across the printer every ten seconds of film time, so that the image of the piece of film material, containing its figurative image moves into the projected frame from the left, across the frame and out across the optical soundtrack area to the right. Featuring a new line in Musical Pullovers.

MY MOVIE MELODIES

Jun’ichi Okuyama, Japan, 1980, b/w, sound, 7 min

In this film, the image produces the sound, and the sound is the image. It catches sight of landscapes and incidents. The various images are used to cover an extensive range of sounds. The principal melody is a radiograph of a comb.

MUSICAL STAIRS

Guy Sherwin, UK, 1977, b/w, sound, 10 min

I shot the images of a staircase specifically for the range of sounds they would produce. I used a fixed lens to film from a fixed position at the bottom of the stairs. Tilting the camera up increases the number of steps that are included in the frame. The more steps that are included in the frame the higher the pitch of sound. A simple procedure gave rise to a musical scale (in eleven steps) which is based on the laws of visual perspective. A range of volume is introduced by varying the exposure. The darker the image the louder the sound (it can be the other way round but Musical Stairs uses a soundtrack made from the negative of the picture). The fact that the staircase is neither a synthetic image, nor a particularly clean one (there happened to be leaves on the stairs when I shot the film) means that the sound is not pure, but dense with strange harmonies.

L’ARRIVÉE

Peter Tscherkassky, Austria, 1998, b/w, sound, 3 min

Just as the record player needle has to find the right groove, “L’Arrive” has to settle into the perforation tracks before the narrative line can develop. A train arrives in a station where a hand-instigated collision with another train takes place. The event is not just a depiction, but a battle of the material itself. This is not the end, but the transition to a kiss, the Happy End. L’Arrive demonstrates where cinema begins – with the spectacular, and where it ends – with intimacy. (Bert Rebhandl)

SHUTTER

Taka Iimura, 1971, Japan, b/w, sound, 22 min

Using two projector speeds and various camera speeds, Iimura photographed the light thrown onto a screen by a projector with no film running through it. Because of the disparities between the speeds of the camera and projector shutters, the resulting footage, which he printed first in positive, then in negative, creates a series of flicker effects. One of the more interesting of those many works which have attempted to explore the visual potential of film process and materials. (Scott MacDonald)