Came the Loop Before the Sampler

Date: 6 May 2000 | Season: Oberhausen 2000 | Tags: Oberhausen Film Festival

CAME THE LOOP BEFORE THE SAMPLER

Saturday 6 May 2000, at 10:00pm

Oberhausen Lichtburg Filmpalast

A film programme conceived as a celebration of the loop in its purest form, from the days before its inherent, repetitive beauty was abused by the talent-challenged masses of modern musicians. I oppose the use of drum loops and sampled sections “borrowed” from other people’s hard work in order to compensate for an individual’s lack of creativity. Imitation is the highest form of flattery, but only if it is done in an intelligent manner. There are clever (and respectful) ways in which to quote someone else’s material that bears no relation to using another’s talent to counteract your lack of imagination. The programme is partially conceived as an audio / visual assault on the sample-mongers, but in turn provides divine retribution for those of who appreciate the loop in it’s absolute, most crafted form.

Robert Nelson, Oh Dem Watermelons, 1965, 12 min

Peter Kubelka, Adebar, 1956-57, 1.5 min

Anthony Balch & William Burroughs, The Cut-Ups, 1967, 10 min

Keewatin Dewdney, The Maltese Cross Movement, 1967, 8 min

Joyce Wieland, 1933, 1967, 4 min

Owen Land (formerly known as George Landow), Thank You Jesus for the Eternal Present: 1, 1973, 6 min

Chris Garratt, Exit Right, 1976, 5 min

Standish Lawder, Runaway, 1969, 6 min

Malcolm Le Grice, Reign of the Vampire, 1970, 15 min

Bruce Conner, Looking for Mushrooms, 1961-67/1995, 14 min

Note: Although it was only announced as the second film in the programme, Adebar by Peter Kubelka was projected eight times, between all the other films.

PROGRAMME NOTESCAME THE LOOP BEFORE THE SAMPLER

Saturday 6 May 2000, at 10:00pm

Oberhausen Lichtburg Filmpalast

OH DEM WATERMELONS

Robert Nelson, USA, 1965, 16mm, colour, sound, 12 min

The soundtrack to Oh Dem Watermelons was created by Steve Reich, who is now recognised as one of the first composers to use tape loops, and short repetitive phrases, in “serious” (modern classical) music. To accompany the film, Reich took a parody of a Stephen Foster song and wrote a loop into the melody. The resulting score, which is sung by a chorus of voices, repeats the “Watermelon” in the lyric in a manner which mirrors the repetitive treatment of the unfortunate fruits on the screen.

“The film cost $280 to make, including the cost of a dozen watermelons. We all had a good time running around the Mission District and Portrero Hill busting up watermelons, showing-off and having fun. A few weeks later when we had the film roughly edited, I ran it silent for Ron and Saul and a few people at the Mime Troupe. There was deadly silence and it looked awful. Everyone was embarrassed for me and didn’t know what to say. I faked it by saying it was good and not to worry. A few days later Steve Reich composed the soundtrack and got all the people to sing their parts the right way. The track has helped the film a lot. The film has won a lot of prizes all over the world … and I bought a lot of equipment with the prize money I got for it.” (Robert Nelson)

ADEBAR

Peter Kubelka, Austria, 1956-57, 35mm, b/w, sound, 1.5 min

The spectator of Peter Kubelka’s Adebar benefits greatly from repeated viewing. In fact, the filmmaker distributes both this and the related work Schwechater (1957-58), on reels containing two, five, or seven successive prints. These two short films present a highly refined, economical use of sound and image that are intricately measured against each other. To construct Adebar, Kubelka devised five self-imposed rules regarding the sequencing of the eight chosen sections (of which six have movement and two are stills) and applied these rules to the editing process. The integrated soundtrack is assembled from four twenty-six frame phrases of Pigmy music.

“In the attempt to find for film binding compositional principles of a syntactical-formal nature, Kubelka proceeds in a way analogous to music, especially Webern’s. Filmic time was conceived as ‘measurable’ in the same way as musical time; tones as ‘time-points’ became the frames of film. Just as Webern reduced music to the single tone and the interval, so Kubelka reduced film to the film-frame and the interval between two frames. Just as the law of the row and its four types determined the sequence of tones, pitches, etc., so now the sequence of frames, and of the frame-count, phrases in Vertov’s terminology, positive and negative, timbre, emotional value, silence, etc; between these factors as in serial music, the largest possible number of relationships were produced. It was for this reason that Kubelka also called these films ‘metrical films’. For the metrication of the material already established in Mosaik Im Vertrauen now became a metrication of the single frames. It passed over, so to speak (as with Webern) from the thematic organisation to the organisation of the row, and like the latter he viewed the number opf frames as a function of intervals. Adebar, a film commissioned by the bar of the same name, is the first pure Viennese formal film to be generated by these considerations.” (Peter Weibel)

THE CUT-UPS

Anthony Balch & William Burroughs, UK, 1967, 16mm, b/w, sound 10 min

The Cut Up technique, which was developed for literature by William Burroughs and Brion Gysin, was adapted and applied to film by Anthony Balch. The footage was originally shot in 1961-65 for an uncompleted film called Guerrilla Conditions, and was subsequently edited intor four separate sequences. After determining an optimum length of shot that would allow a viewer to recognise imagery without being able to interpret it, Balch instructed a lab technician to “take a foot from each roll and join them up”, making this an early (and unrecognised) Structural film. As with Oh Dem Watermelons, the soundtrack of The Cut Ups relies more on a written score than it does on a looped tape. Burroughs and Gysin read the well orchestrated, persistent text, which is based on a Scientology manual.

“The Cut Ups was a radical cinematic experiment; primarily this was due to its re-negotiation of the ontology of film. The process of viewing The Cut Ups is analogous to the process of viewing the Dreamachine; like the Dreamachine the film creates a rhythmic pattern of flickering light and images across the audience’s retinas; as Ian Sommerville noted, “Flicker may play a part in cinematic experience. Films impose external rhythms on the mind, altering the brain waves which are otherwise as individual as finger-prints”. The Cut Ups presented images which were simultaneously at random, yet precise, with scenes structured according to lengths of celluloid rather than of action or narrative. The only order imposed on the film is that which attempts to remove coherent, linear, narrative structure. The film demands that an audience experience film differently: as pure light and motion. Devoid of ‘rational logic’, conventional narrative, and recognisable visual pleasure; instead The Cut Ups constructs the audience’s relation with film as one based on the aesthetic of pure speed, as images strobe past the audience’s collective retina.” (Jack Sargeant)

THE MALTESE CROSS MOVEMENT

Keewatin Dewdney, Canada, 1967, 16mm, colour, sound, 8 min

A loop of the Beach Boys’ song “Gettin’ Hungry” from the “Smiley Smile” album provides an aural background to this cleverly constructed work by an undervalued Canadian filmmaker. One aspect of the film is concerned with using pictures to visually represent words, in a manner comparable to Associations (1975) by English filmmaker John Smith. As a result of the reorganisation of fragments of sound and imagery from throughout the film, the viewer suddenly becomes aware of an emerging objective, which triumphantly comes together in the final montage.

The film reflects Dewdney’s conviction that, “the projector, not the camera, is the filmmaker’s true medium”. The form and content of the film are shown to derive directly from the mechanical operation of the projector – specifically the animation of the disk and the cross illustrates graphically (no pun intended) the projector’s essential parts and movements. It also alludes to a dialectic of continuous-discontinuous movements that pervades the apparatus, from its central mechanical operation to the spectator’s perception of the film’s images … [His] soundtrack demonstrates that what we hear is also built out of continuous-discontinuous ‘sub-sets’. The film is organised around the principle that it can only complete itself when enough separate and discontinuous sounds have been stored up to provide the male voice on the soundtrack with the sounds needed to repeat a little girl’s poem; “The cross revolves at sunset / The moon returns at dawn / If you die tonight / Tomorrow you’re gone.” (William C. Wees)

1933

Joyce Wieland, Canada, 1967, 16mm, colour, sound 4 min

In striving to interpret the basic visual element of “1933”, scholars have often refused to accept that it may just be a repeated segment of unpretentious, interesting, footage. The film presents an astute, casual view of the street below which certainly throws up some interesting spatial considerations, but Wieland’s real skill was in the shrewd looping, the changes of pace, the mysterious superimposition and the uncompromising soundtrack. In many ways, “1933” seems more like a sculpture that a film. It’s easy to imagine it continually rolling, and not only coming to life when projected.

“While the superimposed title in Sailboat (also 1967) literalizes itself through the images, the title “1933” does nothing of the kind. Joyce Wieland commented that one day after shooting she returned home with about thirty feet of film remaining in her camera and proceeded to empty it by filming the street scene below. She explains in notes: “When editing what I then considered the real footage I kept coming across the small piece of film of the street. Finally I junked the real film for the accidental footage of the street. It was a beautiful piece of blue street … So I made the right number of prints of it plus fogged ends”. The street scene with the white-streaked end is loop-printed ten times, and “1933” appears systematically on the street scene for only the first, seventh and tenth loops. While the meaning of the title, 1933, is enigmatic and has no real and ostensible relationship to the film, in its systematic use as subtitle it becomes an image incorporated into the feel. And in that sense it reaffirms the film itself. It is not the title of a longer work, but an integral part of the work.” (Regina Cornwell)

THANK YOU JESUS FOR THE ETERNAL PRESENT: 1

Owen Land (formerly known as George Landow), USA, 1973, 16mm, colour, sound, 6 min

The soundtrack of Land(ow)’s Thank You Jesus For The Eternal Present: 1 is based upon recordings of conversations with devoted Christians, making it the first film of his directly concerned with Christian subject matter. Only a few discernible phrases are heard as much of these recordings are obscured by a loop of a female voice religiously (or sexually ?) intoning “Oh God, Oh God, Oh God, Oh God”, these sounds being clearly related to the woman’s ecstatic face which is superimposed over the basic footage. Land claims that Thank You Jesus is a series of which only this first segment has been completed.

“Thank You Jesus For The Eternal Present posits, in ingeniously compact visual / aural form, a multitude of eternal dichotomies, among them darkness and light, and the psychic separation of spiritual / sexual (inward) versus material / sexual (outward) striving. Instead of a yin / yang antimony: God and the Devil in female guise. The fervently whispered prayers of the woman whose face is seen in close up have transported her to a nearly sexual, religious ecstasy; and each reappearance of the worldly, sexually powerful ‘corporation’ woman is heralded by a sharp, synchronous thunderclap and camera flash. Yet it is she – the world woman, Venus in Furs – full colour, in glory, who nods in assent, in sole possession of the screen at film’s end.” (John Luther Schofill)

EXIT RIGHT

Chris Garratt, UK, 1976, 16mm, b/w, sound, 5 min

The early films of Chris Garratt frequently use looping and staggered progressions such as two-steps-forward-one-step-back. This kind of editing scheme is best demonstrated in Romantic Italy (1975), which reassembles a found travelogue depicting the historic city of Florence using a schedule of 1234234534564567…etc., utterly deconstructing the original passage of the footage while keeping it in order. Exit Right deals with two of the main concerns of English filmmaking in the mid-1970s – an investigation of printing techniques (the London Co-operative had its own home made, much used, optical and contact printers), and the visual creation of sound by printing images over the optical track (Guy Sherwin, Lis Rhodes and many others investigated this possibility).

“A one second shot of me walking into the shot wearing a striped jersey was printed repeatedly; this strip of negative was moved laterally across the printer every ten seconds of film time, so that the image of the piece of film material, containing its figurative image moves into the projected frame from the left, across the frame and out across the optical soundtrack area to the right. Featuring a New Line in musical pullovers.” (Chris Garratt)

RUNAWAY

Standish Lawder, USA, 1969, 16mm, b/w, sound, 6 min

For Runaway, Lawder took four seconds of a commercial animation called The Fox Hunt and made a continuous loop that was re-photographed and sequentially abstracted so the cartoon dogs seem unable to escape the frame. The humorous display of visual techniques is accompanied by a jaunty organ track, which is restrained in a manner similar to the dogs before being allowed to progress to its conclusion. Runaway is a successful early attempt to integrate the developing video technology into contemporary film practice.

“A cartoon image of dogs rushing across the screen, then reversing their direction, is looped over and over, to the accompaniment of a sprightly tune played on an organ. The footage is seen on television, then as film, then back on TV, deteriorating and recovering clarity as the repetitions roll on. [Lawder] achieves the perfection of all his techniques in a small film called Runaway, in which he uses a few seconds of cartoon dogs chasing a fox. By stop motion, reverse printing, video scanning, by manipulating a few seconds of an old cartoon, he creates a totally new and different visual reality that is no longer a silly, funny cartoon. He elevates the cartoon imagery to the visual strength of an old Chinese charcoal drawing.” (Jonas Mekas)

REIGN OF THE VAMPIRE

Malcolm Le Grice, UK, 1970, 16mm, b/w, sound, 15 min

While the repetitious images in Reign Of The Vampire are clearly assembled systematically, the strategy is not necessarily perceptible to the audience. Le Grice has stated that appreciation of the system is kinetic rather than intellectual. The continuous, subtle changes of the loops appear more closely suitable for brainwashing than as material for rational interpretation. When these images are coupled with a similarly relentless, slowly evolving soundtrack, the overall effect is one of cerebral subversion.

“This film could be considered as a synthesis of the “How To Screw The C.I.A.” series. It is formally based on the permutive loop structure, superimposing a series of three pairs of image loops of different lengths with each other. The images include elements from all the previous parts of the series. The film sequences, which make up loops, are again chosen for their combination of semantic relationships, and abstract factors of movement. The soundtrack is constructed for the film, but independently, and has a similar loop structure.” (Malcolm Le Grice)

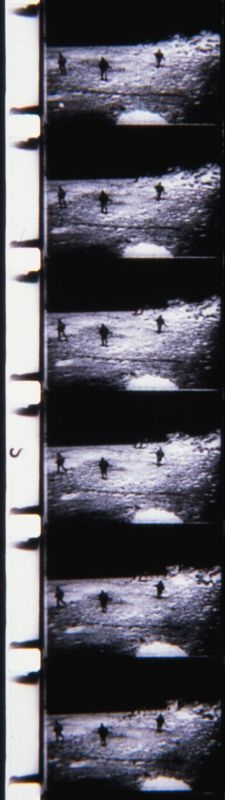

LOOKING FOR MUSHROOMS

Bruce Conner, USA, 1961-67/1995, 16mm, colour, sound, 14 min

In its present form, Looking For Mushrooms is a new realisation of two previous works that used the same title and contained the same intense barrage of footage. This highly edited reel is a combination of material shot in San Francisco in 1959, and during a trip to Mexico two years later. The film was first exhibited in 1965 as a silent fifty foot 8mm reel projected at a speed of 5fps and lasting eleven minutes. In 1967, the same film was released on 16mm (at 24fps) with a soundtrack of “Tomorrow Never Knows” from The Beatles’ “Revolver” album. Nearly thirty years later, Conner took this and another slow-speed 8mm reel, Report: Television Assassination (1963-64) – a different, but related, work to Report (1963-67) – and step printed them both onto 16mm using a frame ratio of 5:1. This new version of Looking For Mushrooms was accompanied by a recording of “Poppy Nogood and the Phantom Band” by Terry Riley, a composer who took the process of tape looping to new, unequalled heights with his music in the late 1960s. From the “Rainbow In Curved Air” album, through his all night concerts, to his organ improvisations of the 1970s, Riley refined a technique of combining solo live performance with his own system of real time tape looping that puts today’s musicians and technology to shame.

“Looking For Mushrooms unfolds at one and the same time as a hyperactive, realistic recording – a travel diary – and as a freewheeling, almost hallucinatory spectacle. The arc of the film’s structure suggests a shift from the material world shown in great detail to a purely ideational realm of art. What reconciles these seemingly contradictory zones is Conner’s mediating sensibility … In 1995, Conner revised Looking For Mushrooms, [which was] step-printed and slowed down by a factor of five, and given a new score. The film gained a heightened level of visibility through a pacing that restrained the abstracting speed of the original shooting, cutting, and superimposition; and it acquired a potent acoustic counterpoint through the addition of a performance by Terry Riley that highlights the microrhythms of Conner’s masterful camera work and complex montage.” (Bruce Jenkins)