Bruce Baillie & Chick Strand

Date: 7 November 1998 | Season: Underground America

BRUCE BAILLIE & CHICK STRAND

Saturday 7 November 1998, at 7:00pm

London Lux Centre

An evening of films by the founders of Canyon Cinema, the west coast’s version of the Film-Makers’ Cooperative, which is still one of the major distributors of experimental work. Bruce Baillie is one of the most American of directors and he exposes and investigates American myths and dreams in complex multi-layered masterpieces such as Mass (For The Dakota Sioux) and Quixote. Chick Strand’s short films are simple and sensuous haiku poems.

Bruce Baillie, Mass (For The Dakota Sioux), 1964, 24 min

Bruce Baillie, Quixote, 1964-67, 45 min

Bruce Baillie, Castro Street, 1966, 10 min

Bruce Baillie, All My Life, 1966, 3 min

Chick Strand, Kulu Se Mama, 1966, 3 min

Chick Strand, Waterfall, 1967, 3 min

Chick Strand, Anselmo, 1966, 4 min

Chick Strand, Angel Sweet Blue Wings, 1966, 4 min

BRUCE BAILLIE & CHICK STRAND

Saturday 7 November 1998, at 7:00pm

London Lux Centre

Bruce Baillie was a key figure in the development of the film community on the West Coast of the USA. In 1960, as he was beginning to make films of his own, he started the Canyon Cinema screenings in the backyard of his house in Canyon, California. These informal gatherings were the first time the West Coast had a regular forum for experimental film since the Art in Cinema series at the San Francisco Museum of Art some ten years before. After Baillie moved to Berkeley in 1962, Chick Strand became involved in the running of the collective, they started to film newsreels of the events around their neighbourhood, and another member of the group, Ernest Callenbach, started the Canyon Cinemanews periodical. In the mid 1960s Canyon Cinema was formed into a distribution group similar to that of the Film-Makers’ Cooperative. Baillie left the organisation soon after, but it continues today as a major source for renting experimental films.

Baillie’s films take a uniquely American outsider’s view of the world around him. After early narratives like On Sundays (1960-61) and newsreels such as Mr Hayashi (1961), his first major personal statement was To Parsifal (1963), a poem to the summer based on the legend of Parsifal and inspired by the music of Wagner. His next film, Mass (For The Dakota Sioux) (1964), is an incredible requiem that was conceived on the occasion of President Kennedy’s murder, and was partly the result of a journey back to his original home in South Dakota. It is a densely layered tribute to the American Indian and a harsh critique of modern society, and remains it one of the classics of the experimental genre.

MASS (FOR THE DAKOTA SIOUX)

Bruce Baillie, USA, 1964, 16mm, b/w, sound, 24 min

“Pictures of a civilization which subscribes to the traditional life-celebrating mass yet leaves a man to die alone on a street corner. There have been many documentary films presenting the horrors of city life, but Baillie’s Mass goes far beyond documentation, providing us with a deeply felt and deeply moving film that is truly cinematic in concept and in execution.” (Willard Van Dyke)

“The film has a very strong critical thesis: it’s against contemporary society, buildings, pollution – all the rest of it – and it’s for the at least implied joy of nature and selfhood and being human !” (Bruce Baillie interviewed by Scott MacDonald, 1989, from the book A Critical Cinema 2, 1992)

Baillie’s next film was a deeper journey into the heart of America, and in some ways it can be seen as an extension of Mass. It was filmed on a cross country trip in 1963-64 and covers themes raised by Baillie’s interpretation of the Don Quixote books. As social analysis it investigates much of the American experience, from the Indians to Wall Street to Vietnam. It was originally planned as a double screen projection, until the final edit of 1967 produced a single screen film that often uses masterful superimpositions to portray an extremely personal journey.

QUIXOTE

Bruce Baillie, USA, 1964-67, 16mm, colour, sound, 45 min

“Baillie’s trip is wedged between two generations of youthful nomads; the Beats (contemporaneous with Hollywood’s heydey of Western expansion) on one side, the hippy transhumances (and Easy Rider) on the other. That Quixote could be claimed, at different times, by each is a sign of its hinged position to two vastly different projects. Unlike either generation, Baillie could not be comfortable with the ethos of noncommitment or, for that matter, transcendence. Like both he would be in but not of, and vice versa, except that in Quixote, these states are emblematic of the conquistador, an altogether diaristic myth.” (from the essay Quixote And Its Contexts by Paul Arthur, Film Culture #67-68-69, 1979)

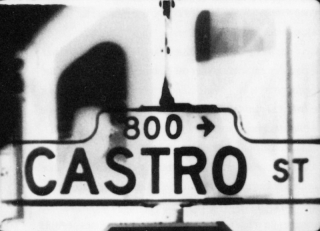

After mastering superimposition in the editing of Quixote, Baillie further advanced his technique in Castro Street (1966). The film is an abstracted portrait of a street in Richmond, executed as an incredibly rich montage of images which the filmmaker sees as the coming of consciousness.

CASTRO STREET

Bruce Baillie, USA, 1966, 16mm, colour, sound, 10 min

“Inspired by a lesson from Eric Satie; a film in the form of a street – Castro Street, running by the Standard Oil Refinery in Richmond, California … switch engines on one side and refinery tanks, stacks and buildings on the other – the street and film, ending at a red lumber company. All visual and sound elements from the street, progressing from the beginning to the end of the end of the street. One side is black and white (secondary), and one side is color – like male and female elements. The emergence of a long switch engine shot (black and white solo) is to the filmmaker the essence of consciousness.” (Bruce Baillie, New York Film-Makers’ Cooperative Catalogue #5, 1971)

All My Life (1966) is a simple but effective film made in a single three minute pan over a picket fence in Mendocino. It succeeds in condensing a complete statement in a single shot. The same year he made Still Life (1966) using a similar approach. His next film was Valentin de las Sierras (1968), a beautifully composed ethnographic portrait of a Mexican community. Baillie then made the epic Quick Billy (1967-70), a four reel film of his psychic journey and physical recovery during a period of transformation, a personal Tibetan Book Of The Dead. In the mid 1970s Baillie shot, but has not yet completely edited, Roslyn Romance (is it really true ?) (1973-78), which follows his quest for spiritual enlightenment in a small village in Washington state.

ALL MY LIFE

Bruce Baillie, USA, 1966, 16mm, colour, sound, 3 min

“There were three days: the peak day was the first day I noticed the light. I had this outdated Ansco film I wanted to use. But I didn’t want to make a film. By that time, I knew the toll making a film can take. But the second day the light was still marvelous. A friend was with me, and we started to drive back to San Francisco, and suddenly I said “No, I cannot turn my back on this !” We stopped, and I got the tripod, fixed it real solid. Then I practiced and had her call off the minutes: we had about three minutes to get up into the sky in one roll, one continuous shot. All My Life came out well. It was inspired by the light, and by the early Teddy Wilson / Ella Fitzgerald recording.” (Bruce Baillie interviewed by Scott MacDonald, 1989, from the book A Critical Cinema 2, 1992)

Alongside Bruce Baillie, Chick Strand was one of the forces behind the formation of the Canyon Cinema collective. Her early works share Baillie’s sense of spirituality, but concentrate more on the printing process than in the precise construction of the filmed frame. Strand also incorporates found footage into her work. After her short Haiku films of 1966-67 she went on to make a series of ethnological documentaries including Cosas de Mi Vida (1965-76) and Soft Fiction (1979), as well as collage films like Cartoon le Mousse and Loose Ends (both 1979).

KULU SE MAMA

Chick Strand, USA, 1966, 16mm, colour, sound, 3 min

“These short films, simple and sensuous as Haiku poems, are early works of this pioneer West Coast filmmaker who was the co-founder with Bruce Baillie of Canyon Cinema in San Francisco and later, after her marriage with cartoon artist Neon Park, moved to Los Angeles to help form the Film-Makers’ Cooperative there. Although trained as an anthropologist and ethnographer her interest in cinema is primarily in the abstract and kinetic visual phenomena that are inherent in film, such as positive / negative juxtapositions, chirality, flickers, etc…” (William Moritz on Chick Strand, London Film Makers’ Co-Op Catalogue, 1977)

WATERFALL

Chick Strand, USA, 1967, 16mm, colour, sound, 3 min

“A film poem using found film and stock footage altered by printing, home development and solarization. It is a film using visual relationships to invoke a feeling of flow and movement.” (Chick Strand, Canyon Cinema Film / Video Catalogue #7, 1992)

ANSELMO

Chick Strand, USA, 1966, 16mm, colour, sound, 4 min

“An experimental documentary in the sense that it is a symbolic reenactment of a real event. I asked a Mexican friend what he would like most in the world. His answer was “A double E flat tuba”. I thought it would be easy to find one at Goodwill. This wasn’t so, but a sympathetic man in a music store found a cheap but beautiful brass wrap-around tuba. I bought it, smuggled it into Mexico and gave it to my friend in the desert. The film is a poetic interpretation of this event in celebration of wishes and tubas.” (Chick Strand, Canyon Cinema Film / Video Catalogue #7, 1992)

ANGEL SWEET BLUE WINGS

Chick Strand, USA, 1966, 16mm, colour, sound, 4 min

“Having seen A Movie and the possibilities therein, I knew it was possible to work with old film and not be intimidated at all about it – lifting things and rearranging them, doing collage. It’s just sort of a miracle to find some junk nobody wants. All that stuff I got would have been thrown away, except for the few pieces I heisted from a couple of prints. I was so entranced by the image itself and how I could mess with it, stick it in another context in a sort of semi-outrageous way. Nothing is sacred. You just rip it out of one context, or leave a couple of the little sub-contextual things in it, and mix the whole thing up with something else entirely, and make up a context.” (Chick Strand speaking to William C. Wees, 1991, from his book Recycled Images, 1993)