Ways of Seeing

Date: 5 November 1998 | Season: Underground America

WAYS OF SEEING

Thursday 5 November 1998, at 7:00pm

London Lux Centre

An exploration of life on film through the eyes of different film-makers. In Recreation almost every subsequent frame is composed of completely disparate images. Stan Brakhage is one of the most productive and highly regarded masters of avant-garde film and Prelude: Dog Star Man is a major work. Death In The Forenoon is a short comedy utilising live action and animation. Ed Emshwiller was a remarkable technician and visionary, Relativity is his epic work about man’s place in the universe. Nightspring Daystar is a poetic notebook of images. The actor Jerry Joffen made unique film diaries and Bill Brand demonstrated a formal and direct way of presenting life through film that was important to the Structural movement.

Robert Breer, Recreation I, 1956-57, 2 min

Stan Brakhage, Prelude: Dog Star Man, 1961, 25 min

David Brooks, Nightspring Daystar, 1964, 18 min

Jerome Hill, Death In The Forenoon or Who’s Afraid Of Ernest Hemmingway, 1933-65, 2 min

Ed Emshwiller, Relativity, 1966, 38 min

Jerry Joffen, How Can We Tell The Dancer From The Dance?, 1970, 10 min

Bill Brand, Moment, 1972, 23 min

WAYS OF SEEING

Thursday 5 November 1998, at 7:00pm

London Lux Centre

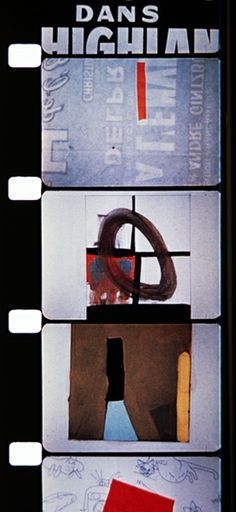

Robert Breer is another painter who found the canvas so restricting that he moved into cinema. All of his films seek to explore “the domain between motion and still pictures”. His first film was Form Phases I (1952), which was clearly influenced by Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling. In 1954 he made an innovative loop titled Image By Images I, in which each frame was independent of the next and there was no perceptual continuous motion. He further developed this new collage technique in the films leading up to Recreation I (1956-57) in which rapid, disparate, single-frame sequences are occasionally interrupted by slightly longer shots in an attempt to subvert the persistence of vision. Throughout the 1960s Breer refined his animation style in films such as Inner And Outer Space (1960) and Fist Fight (1964), before adapting his work process to include drawing on filing cards which he could flip through to view the movement. He also began to make and exhibit Mutoscopes of his card animations, and in the late 1960s built “floats”, small kinetic sculptures that moved along the ground at a very slow pace. Breer later started to combine live footage with his animations. He continues make short films that are always infused with gentle wit, some of the best examples are 1969 (1968), Gulls And Buoys (1972), Fuji (1973) and LMNO (1978).

RECREATION I

Robert Breer, USA, 1956-57, 16mm, colour, sound, 2 min

“I decided since I don’t know about continuity, I don’t have to think about it, and I’ll just put it out of my mind. I’ll do it in a very methodical way, which was by fracturing, shattering the image so there wasn’t a flaw in it. So the collage thing was kind if deliberate—like the first ones, Recreation and the loops I made before that—were done really in a kind of deliberate feeling of wonderment: “What the hell will this look like?” and “I don’t want to know, I can attach no value to it. I don’t know whether this is cinema or not, it doesn’t matter”.” (Robert Breer interviewed by Jonas Mekas and P. Adams Sitney in 1971, printed in Film Culture #56-57, 1973)

It is not possible to do justice to the work of Stan Brakhage in a single paragraph, or by showing one film in a season such as this. Brakhage continues to be incredibly prolific, making it hard to summarise his work. He began filmmaking with Interim (1953), a brief romantic narrative, and then made a series of trance films (including Reflections On Black and The Way To Shadow Garden, both 1955) inspired in part by his friendship with Maya Deren. Anticipation Of The Night (1958) marked a new turning point signifying his fascination with light and fragmentation of the normal visual world. Prelude (1961) is the opening section of Dog Star Man (1961-64), a major opus on the creation of the universe that is widely regarded as his greatest achievement. On its release it made a monumental impact upon the work of experimental filmmakers. Dog Star Man was then incorporated in The Art Of Vision (1961-65), a four-and-a-half hour long silent epic. In 1963 he made Mothlight by pasting moth wings and plant material between strips of mylar tape. After his 16mm camera was stolen he worked on the series Songs 1-29 (1964-1986), while continuing to make other films and series throughout the next decades. Brakhage is a great believer in the purity of cinematic vision and almost all of his films since 1955 have been silent. His recent works have all been abstract, made by painting directly onto 35mm or 70mm film.

PRELUDE: DOG STAR MAN

Stan Brakhage, USA, 1961, 16mm, colour, silent, 25 min

“In Prelude, the new Brakhage reaches his highest peak so far and gives to modern cinema one of its authentic and incontestable masterpieces. A film that is a poem, a metaphysical thought, a visual symphony, I don’t know what – it is beyond description in words. It is all cinema.” (Jonas Mekas, Village Voice Movie Journal, 1961)

“I thought of Dog Star Man as seasonally structured; but also while it encompasses a year and the history of man in terms of image material (e.g. trees become architecture for a whole history of religious monuments or violence becomes the development of war), I thought it should be contained within a single day. I wanted Prelude to be a created dream for the work that follows rather than Surrealism which takes its inspiration from dream; I stayed close to the practical use of dream material. One thing I knew for sure (from my own dreaming) was that what one dreams just before waking structures the whole day. Since Prelude was based on dream vision as I remembered it, it had to include ‘closed-eye vision’.” (Stan Brakhage quoted in P. Adams Sitney’s book Visionary Film, 1974)

David Brooks was the first director of the New York Film-Makers’ Cooperative when it was formed in 1962. He made a series of short diary films before his untimely death in 1969. His work displays a freedom inherent in the use of a hand-held camera together with a natural sense of timing. In 1968, Brooks completed his longest film, The Wind Is Driving Him Toward The Open Sea, a melancholy unstructured narrative of reflection and seeking.

NIGHTSPRING DAYSTAR

David Brooks, USA, 1964, 16mm, colour, sound, 18 min

“Nightspring Daystar, made when Brooks was only nineteen, is his most inspired. The film centers on the everyday: Brooks’ room, views out of windows, various travels, a woman, concerts at the Village Gate and Apollo Theatre, the night lights of the city. More than any other film I can think of, it operates on the level of pure feeling, evoking in the viewer various moods and memories.” (from J.J. Murphy’s essay The Films Of David Brooks, Film Culture #70-71, 1983)

Jerome Hill was the heir to the James J. Hill railroad fortune. While at Yale, he co-directed a feature film of Tom Jones (1927), and after leaving college he spent the following years travelling, painting and studying in Europe. In 1932 he bought one of the first Eastman Kodak 16mm cameras and began to pursue filmmaking, shooting some personal footage but mostly making documentaries. His film on Albert Schweitzer (1950-57) won an Academy Award and soon after he met Jonas Mekas and became aware of the independent film movement. Hill made a dream film, The Sand Castle, in 1961, combining live footage and hand painted sequences. After the feature Open The Door And See All The People (1964) (an absurd fantasy starring Taylor Mead and others), he made his first short film Death In The Forenoon or Who’s Afraid Of Ernest Hemingway (1933-65) which brought together material that was shot thirty years apart. It is both dark and humorous and was originally titled Anti-Corrida. More short films followed and his last completed work was the autobiographical Film Portrait (1970) which utilised the home movies of his childhood alongside new footage. Jerome Hill died in November 1972. Throughout his lifetime he used his inheritance to support many independent filmmakers and he was the original sponsor of Anthology Film Archives.

DEATH IN THE FORENOON OR WHO’S AFRAID OF ERNEST HEMINGWAY

Jerome Hill, USA, 1933-65, 16mm, colour, sound, 2 min

“I must tell you that Peter Kubelka (who is staying with us this month) (and who is, to my way of thinking, the greatest ‘perfectionist’ of the film medium, and thus finds it very difficult to ‘like’ anything but his work, a few of mine, and one or two other films in the whole world) DID like your film and was much interested in this unique effect you’ve created … what I call the ‘back-space’. I think the children were actually tempted to look behind the screen—I mean that there is such a play between the shapes you’ve painted and those photographed that the former do very much seem in a different ‘plane’ and definitely as if emerging from behind.” (Stan Brakhage in a letter to Jerome Hill, reprinted in New York Filmmakers’ Cooperative Catalogue #5, 1971)

Ed Emshwiller is widely regarded as one of the finest technicians of avant-garde film. In the 1940s he was one of the world’s leading science-fiction illustrators. After studying painting in Paris, Emshwiller made his first film Dance Chromatic (1959), animating abstract paintings over film of a girl dancing. Other personal films followed and he also spent time as a cinematographer for feature directors. Between 1960-62 he made the amazing Thanatopsis, a live action single frame animation. Relativity (1966) is a metaphorical film about man’s place in the universe. Using an astounding range of cinematic techniques, Emshwiller achieved complete control of time, gravity and scale. It was his most successful film and thereafter he went on to make pioneering works of video art.

RELATIVITY

Ed Emshwiller, USA, 1966, 16mm, colour, sound, 38 min

“The artists’ search for the meaning of his own existence is never-ending and many forms. Ed Emshwiller’s remarkable epic Relativity continues this explanation with extraordinary frankness and rare technical skill. The sequence which symbolically portrays a woman at the moment of sexual climax is one of the most beautiful in the literature of film.” (Willard Van Dyke)

Jerry Joffen is a legendary figure of the Lower East Side, whose impulsive films are often dismissed as home movies. He developed a technique of unplanned multiple exposure similar to that of Piero Heliczer, another character who is often overlooked and undervalued. While sharing a loft with Ron Rice in 1961, Joffen began to make films such as Ineluctable Disaster In The Adventure Of The Stairway Of Infinite Rungs Infinitely Leading Nowhere (1962-63) with the downtown crowd. Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures was premiered at his loft in 1963. As was often the case with Smith, Joffen rarely made definitive edits of his films and preferred to cut them specifically for each screening. In the early 1970s, Joffen became ill and underwent neurosurgery. He returned to the lifestyle of his Rabbinical family and made two religious films. Further surgery led to extensive paralysis and he was bedridden for many years until his death in 1983.

HOW CAN WE TELL THE DANCER FROM THE DANCE ?

Jerry Joffen, USA, 1970, 16mm, colour, sound, 10 min

“Jerry Joffen has so much personality and artistry that even those parts of his films which fail become somehow integrated and work perfectly in the total structure. It has always been in the past that Jerry Joffen’s failures were more interesting than some other artists’ successes. He is a master of destruction. I mean it in a good sense, in the sense of spiritualizing the reality, dissolving time and space.” (Jonas Mekas in the Village Voice Movie Journal, 1965)

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Bill Brand made a number of analytic films that investigated theories of perception and the transference of information. For Moment (1972) he developed a systemic editing procedure to fragment a continuous single shot of a garage from behind a slatted, rotating advertising hoarding. He went on to make the trilogy Acts Of Light (1972-74), “a study of pure colour based on the notion that film is essentially change and not motion”.

MOMENT

Bill Brand, USA, 1972, 16mm, b/w, sound, 23 min

“In a two-and-a-half minute sequence, a simple series of gas station events is seen intermittently through the opening display. This sequence is then divided and rearranged seven times in reverse order. Each time the divisions are greater in number (smaller in size) until finally the film appears to move smoothly backwards, divided by a single frame. The inspiration for the film as well as the title is derived from information theory. There, a ‘moment’ is defined as the shortest duration at which no distinction can be made between units of information. This work is a demonstration and exploration of the line between human information and machine information. It dynamically reveals the film’s basic unit, the frame.” (Bill Brand, New York Film-Makers’ Cooperative Catalogue #7, 1989)