Flaming Creatures

Date: 24 October 1998 | Season: Underground America

FLAMING CREATURES

Saturday 24 October 1998, at 8:45pm

London Barbican Cinema

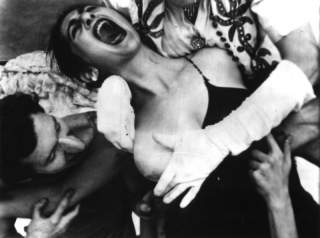

Flaming Creatures was for many years the cause célèbre of the underground, being the subject of high profile busts and seizures, and its Baghdadian vision can still be shocking now. The authorities of the day often used this movie as proof that the underground films were all full of nudity and depravity. It’s maker, Jack Smith, was a key figure in the New York scene and starred in many of the best known films as well as his own unique theatre presentations. The monumental Flaming Creatures is shown here with some forgotten erotic escapades: Jerovi looks at the Narcissus myth, Avocada is a smouldering study of high art writhing, and Soul Freeze by Kuchar Brothers star Bob Cowan explores with shocking intensity the guilty fantasies of a Catholic priest.

Jack Smith, Flaming Creatures, 1962-63, 45 min

Jose Rodriguez-Soltero, Jerovi, 1965, 12 min

Bill Vehr, Avocada, 1966, 37 min

Bob Cowan, Soul Freeze, 1967, 25 min

FLAMING CREATURES

Saturday 24 October 1998, at 8:45pm

London Barbican Cinema

For many people the words “Underground Film” invoke ideas of sexual depravity and cinematic obscenities, but Flaming Creatures (1962-63) and similar films do not use nudity to titillate, rather to express a kind of innocent freedom that became necessary to pursue new ways of uninhibited personal expression. Jack Smith’s most celebrated flick and the court proceedings which followed its release went some way to liberate cinema, breaking down moral barriers which made it possible to present previously taboo subject matter on film.

Jack Smith was born in Ohio in 1932 and moved to New York in the early 1950s where he developed an interest in experimental theatre, and from then up until his death in 1989 he was incredibly prolific as an actor, writer, filmmaker and photographer. His unique and highly opinionated persona informed an inimitable vision that he conveyed through all his works. In the late 1950s he was developing a distinctive style of still photography at his Hyperbole Studio in the East Village – bizarre tableaus of bodies, costumes and informal props which could depict entire worlds in a single frame. One extended photo session led to the publication of The Beautiful Book (1962) by the poet Piero Heliczer’s Dead Language Press. Jack’s first experiences in film were as an actor in movies by Ken Jacobs and Bob Fleischner (Star Spangled To Death, Blonde Cobra and Little Stabs At Happiness all date from 1957-60). Throughout the next decade Smith would appear in many classic underground films including Chumlum (Ron Rice, 1965), Camp and Hedy (both by Andy Warhol, 1965), Brothel (Bill Vehr) and The Illiac Passion (Gregory Markopoulos, 1967). His first completed film was Scotch Tape (1959), so named after the piece of tape which was unwittingly wedged in the camera gate, was made quite casually at one of the locations of Ken Jacobs’ epic Star Spangled To Death. Three years later on the roof of the Windsor Theatre Jack meticulously fashioned his masterpiece Flaming Creatures out of a mythology of Hollywood, 1001 Arabian nights and the spirit of Maria Montez. The outdated black and white stock he used enhances the timeless and otherworldly aura of the scenarios. A review of the first screening of the then unfinished film hints at the tour de force that was about to be unleashed upon the public.

“Jack Smith just finished a great movie, Flaming Creatures, which is so beautiful that I feel ashamed even to sit through the current Hollywood and European movies. I saw it privately, and there is little hope that Smith’s movie will ever reach the movie theatre screens. But I tell you, it is a most luxurious outpouring of imagination, of imagery, of poetry, of movie artistry – comparable only to the work of the greatest, like Von Sternberg.” (Jonas Mekas in the Village Voice Movie Journal, 1963)

Jonas Mekas was an unfailing patron of Jack Smith and Flaming Creatures, and was directly involved in the now legendary screening at the Knokke-le-Zoute Experimental Film Festival in Belgium and the court cases which followed seizure of the film back in New York in 1964. His efforts went unappreciated by Smith, who later made Mekas (“Uncle Fishhook”) the villain in many of his writings and theatre productions. Almost immediately after completing Flaming Creatures, Jack started shooting Normal Love (1963), a sumptuous colour film populated by a large all-star cast of underground celebrities (Smith regarded the subjects of his films the “Superstars of Cinemaroc”, an early precursor of the Andy Warhol Factory). This and subsequent movies such as the incredible No President (1967-70) were never assembled into definitive versions and were constantly re-edited for individual screenings or partially used in his extraordinary theatre presentations of the 1970s.

FLAMING CREATURES

Jack Smith, USA, 1962-63, 16mm, colour, sound, 45 min

“At once primitive and sophisticated, hilarious and poignant, spontaneous and studied, frenzied and languid, crude and delicate, avant and nostalgic, gritty and fanciful, fresh and faded, innocent and jaded, high and low, raw and cooked, underground and camp, black and white and white on white, composed and decomposed, richly perverse and gloriously impoverished, Flaming Creatures was something new under the sun. Had Smith produced nothing other than this amazing artifice, he would still rank among the great visionaries of American film.” (from J. Hoberman’s essay in the book Jack Smith: Flaming Creature, His Amazing Life and Times, 1997)

In the latter half of the 1960s Jose Rodriguez-Soltero created a series of profoundly beautiful films including El Pecado Original (1964), Lupe (1966) and Dialogue With Che (1968). His most notorious is Jerovi, an exploration of the Narcissus myth in which a young male performs unashamed self-love in a lush garden setting.

JEROVI

Jose Rodriguez-Soltero, Puerto Rico-USA, 1965, 16mm, colour, silent, 12 min

“Cinema is a search. Everytime I pick up a camera or see a film I sense a rhythm, a force which impels me to act, to move, to make – no reasons can be given to exhaust the meanings of those forces … My work has been a slow exercise in this search and in sending that rhythm … I haven’t made a film I’m satisfied with completely. I am preparing to live, to reach those personal truths which give me faith. Each of my films is a development, although at times erratic, of my being.” (Jose Rodriguez-Soltero, Film-Makers Lecture Bureau Catalogue #1, 1969)

Bill Vehr made grandiose and exotic costume epics reminiscent of the style of Jack Smith. Avocada is a silent film designed to be accompanied by ethnic Peruvian music. It stars Carole Morell in an electrifying study of high-art writhing, beautifully photographed in glorious Technicolor. His second film Brothel (1966) was similarly transcendent and featured Jack Smith, Mario Montez and Piero Heliczer. In 1968, while returning from a screening in Montreal, both prints of Brothel and a new work-in-progress were seized by Customs officials. As he had no money to go to trial the film was never recovered and has not be seen since.

AVOCADA

Bill Vehr, USA, 1966, 16mm, colour, sound, 37 min

“Bill Vehr is making a magnificent entrance into cinema … His movie Avocada took the Cinematheque’s audience with its beauty – flamboyant, delicate and erotic, and a little bit like Jack Smith, perverted that is to say, and some people will not like it, despite its beauty, because Bill Vehr’s world has been inherited from the famous Marquis, born of the fruits of decadence.” (Jonas Mekas in the Village Voice Movie Journal, 1965)

The Canadian actor Bob Cowan is best known for his starring roles in films by Mike and George Kuchar. He first appeared in Born Of The Wind (1961) and went on to perform in many classics such as Lust For Ecstasy (1963) Sins Of The Fleshapoids (1965) and Color Me Shameless (1967). Cowan was also a prolific filmmaker himself and George Kuchar remembers that “the films he has made are a celebration of the physical loveliness that energised his lust for a richer palette of perception and interpretation via various mediums which give a voice and vision to constipated-carnality”. Soul Freeze is a tough film which explores the temptations and guilty fantasies of a Catholic priest. Cowan has now returned to his native Toronto and continues to make 8mm video films.

SOUL FREEZE

Bob Cowan, Canada-USA, 1967, 16mm, colour, sound, 25 min

“Gathering an inevitable sense of the relentless, Soul Freeze pulses from far flung stasis, the rigidities of outer space, to the multi-peopled cacophony of a demented flesh desert. With feverish momentum, it hovers on waves that break at the edge of reality. The viewer must hope that somewhere he is securely anchored, for as the film unrolls, the universe is fragmented with a clarity merciless in detail. From Soul Freeze there is no escape, only an endless embrace of hell.” (D.J. Ben Levi on Soul Freeze, New York Film-Makers’ Cooperative Catalogue #5, 1971)