Date: 9 November 2000 | Season: Ken Jacobs Nervous System

KEN JACOBS’ NERVOUS SYSTEM

Manchester Cornerhouse

Thursday 9 November 2000, at 7:30pm

ONTIC ANTICS STARRING LAUREL AND HARDY

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1998, Nervous System, b/w, sound, c.60 min

“With his Nervous System film performances, Jacobs wrings changes out of startled frames and makes the infinitesimal matter. Ontic Antics with Laurel and Hardy – the simple shift of a vowel or the advance of a film frame creates a world of definition and character. Basking in that shade of difference he plumbs the frame with surgical decisiveness and amatory delicacy. Welcome to microtonal cinema. Taking Laurel and Hardy’s Berth Marks as point of departure, Jacobs supersedes slapstick, moving into the deeper dimensions of the human comedy. Psychological imbroglios, time-space predicaments, the unruliness of uncooperative gravity, the unlimited expressiveness of the limited body hallucinated into Rorschach-ing deliveries.” (Mark McElhatten)

Hardy walked a thin line between playing heavy and playing fatty. Laurel adopted a retarded squint, with suggestions of idiot savant. Their characters were at sea, clinging to each other as industrial capitalism was breaking up and sinking. Beautiful losers, they kept it funny, buoying our spirits. Laurel and Hardy … forever. (Ken Jacobs)

BERTH MARKS

Lewis R. Foster, USA, 1929, 16mm, b/w, sound, 18 min

Oliver Hardy goes to meet his partner Stan Laurel at the train station. They have a vaudeville act, which involves a bass fiddle, and are on their way to their next performance. They just barely make the train and are led to their berth, wreaking havoc amongst the other passengers in their wake. With much difficulty, they undress in their berth. As soon as they’re ready for bed, they arrive at Pottsville, their destination, and have to hurry off. Once the train has left the station, they discover that they have left their bass fiddle on board. But the situations aren’t important, it’s what the boys do with them – the way Ollie wanders around the station in search of Stan, just missing him several times, and the various contortions the pair try to get into their upper berth – that give the film its fun. Especially nice is the interchange between the boys and the conductor. When Ollie describes himself and Stan to the trainman as a “big-time vaudeville act”, the old man dryly replies, “Well, I bet you’re good !” (Janiss Garza, All Movie Guide)

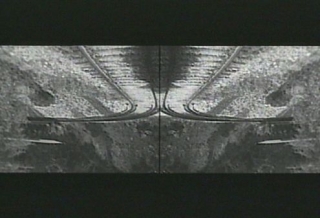

DISORIENT EXPRESS

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1996, 35mm, b/w, silent, 30 min

1906 – Original cinematographer unknown. 1996 – New arrangement by Ken Jacobs. Shots shown as found in “A Trip Down Mount Tamalpais”, the Paper Print Collection, Library of Congress. Optically copied by Sam Bush, Western Cine Lab., Denver, from l6mm to 35mm letterbox format to allow double-image mirroring in 1:85 ratio projection.

The same string of shots, in their entirety, is repeated in various placement and directional permutations. But this film is not a lately arrived example of ‘‘Structural Cinema”, where methods of ordering film materials often came to take on paramount value. (The viewer at some point grasped the method and that could be pretty much it.) I’m for order only to the extent it provides possibilities of fresh experience. For instance, kaleidoscopic symmetry in Disorient Express is not an end in itself. The radiant patterning that affirms the screen plane serves also to provide visual events of an entirely other magnitude. Flat transmutes repeatedly to massive depth illusion; yet that which appears so forcefully, convincingly in depth is patently unreal – an irrational space. The obvious filmic flips and turns (method is always evident) of the scenic trip provide perceptual challenges to our understanding of reality, and we are often unable to see things as we know they are.

With light-source shifted from heaven-sent to infernal, we see a landscape that could never be, except via cinema. A very early recording of a train trip through mountainous terrain, enthusiasm of the adventurous passengers on boisterous display, lends itself to us for a ride into each our own Rorschach wilderness. This careening trip also demands some hanging on, some output of viewer energy. The rightness of the closure (as I see it) was made possible by copying the film, for the last pass, in reverse motion.

Disorient Express takes you someplace else. A spin lasting 30 minutes, you really need to tap into your own reserves of energy. Hang on, please, this is not formalist cinema; order interests me only to the extent that it can provide experience. Watch the flat screen give way to some kind of 3D thrust, look for impossible depth inversions, for jewelled splendour, for CATscans of the brain. I’m banking on this film reviving a yen for expanded consciousness. (Ken Jacobs)

FURTHER NOTES

NOTES ON THE NERVOUS SYSTEM

The Nervous System consists, very basically, of two identical prints on two projectors capable of single-frame advance and “freeze” (turning the movie back into a series of closely related slides.) The twin prints plod through the projectors, frame … by … frame, in various degrees of synchronisation. Most often there’s only a single frame difference. Difference makes for movement, and uncanny three-dimensional space illusions via a shuttling mask or spinning propeller up front, between the projectors, alternating the cast images. Tiny shifts in the way the two images overlap create radically different effects. The throbbing flickering (which takes some getting used to, then becoming no more difficult than following a sunset through passing trees from a moving car) is necessary to create “eternalisms” – unfrozen slices of time, sustained movements going nowhere unlike anything in life (at no time are loops employed). For instance, without discernible start and stop and repeat points a neck may turn … eternally.

The aim is neither to achieve a life-like nor a Black Lagoon 3D illusionism, but to pull a tense plastic play of volume configurations and movements out of standard (2D) pictorial patterning. The space I mean to contract, however, is between now and then, that other present that dropped its shadow on film.

I enjoy mining existing film, seeing what film remembers, what’s missed when it clacks by at Normal Speed. Normal Speed is good ! It tells us stories and much more but it is inefficient in gleaning all possible information from the film-ribbon. And there’s already so much film. Let’s draw some of it out for a deep look, sometimes mix with it, take it further or at least into a new light with flexible expressive projection. We’re urban creatures, sadly, living in movies, i.e. forceful transmissions of other people’s ideas. To film our environment is to film film; it’s also a desperate approach to learning our own minds.

What I’m trying to do is shape a poetry of motion, time / motion studies touched and shifted with a concern for how things feel, to open fresh territory for sentient exploration, creating spectacle from dross … delving and learning beyond the intended message or cover-up, seeing how much history can be salvaged when film is wrested from glib 24 f.p.s. To tell a story in new ways, relating new energy components (words are energy components to a poet) in a system of construction natural to their particularity. To memorialise. To warn.

(Ken Jacobs)

Back to top

Date: 10 November 2000 | Season: Ken Jacobs Nervous System

KEN JACOBS’ NERVOUS SYSTEM

Nottingham Broadway Media Centre

Friday 10 November 2000, at 7pm

CRYSTAL PALACE

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1997, Nervous Magic Lantern, b/w, sound, c.25 min

Impossible movements … impossible spaces … issue forth from a single, somewhat unusual slide projector (of British manufacture) employed in an unexpected way. Cinema without film or electronics. And, as with The Nervous System (utilising pairs of projectors), depth phenomena is produced that can be seen as such without special viewing spectacles, and even by a single eye. (Ken Jacobs)

DISORIENT EXPRESS

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1996, 35mm, b/w, silent, 30 min

1906 – Original cinematographer unknown. 1996 – New arrangement by Ken Jacobs. Shots shown as found in “A Trip Down Mount Tamalpais”, the Paper Print Collection, Library of Congress. Optically copied by Sam Bush, Western Cine Lab., Denver, from 16mm to 35mm letterbox format to allow double-image mirroring in 1:85 ratio projection.

The same string of shots, in their entirety, is repeated in various placement and directional permutations. But this film is not a lately arrived example of ‘‘Structural Cinema”, where methods of ordering film materials often came to take on paramount value. (The viewer at some point grasped the method and that could be pretty much it.) I’m for order only to the extent it provides possibilities of fresh experience. For instance, kaleidoscopic symmetry in Disorient Express is not an end in itself. The radiant patterning that affirms the screen plane serves also to provide visual events of an entirely other magnitude. Flat transmutes repeatedly to massive depth illusion; yet that which appears so forcefully, convincingly in depth is patently unreal – an irrational space. The obvious filmic flips and turns (method is always evident) of the scenic trip provide perceptual challenges to our understanding of reality, and we are often unable to see things as we know they are.

With light-source shifted from heaven-sent to infernal, we see a landscape that could never be, except via cinema. A very early recording of a train trip through mountainous terrain, enthusiasm of the adventurous passengers on boisterous display, lends itself to us for a ride into each our own Rorschach wilderness. This careening trip also demands some hanging on, some output of viewer energy. The rightness of the closure (as I see it) was made possible by copying the film, for the last pass, in reverse motion.

Disorient Express takes you someplace else. A spin lasting 30 minutes, you really need to tap into your own reserves of energy. Hang on, please, this is not formalist cinema; order interests me only to the extent that it can provide experience. Watch the flat screen give way to some kind of 3D thrust, look for impossible depth inversions, for jewelled splendour, for CATscans of the brain. I’m banking on this film reviving a yen for expanded consciousness. (Ken Jacobs)

PHONOGRAPH

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1990, audiotape, 15 min

One-take unedited audiotape. 15 minutes of loud black surround sound. (Ken Jacobs)

“Most ferocious sound I’ve ever heard”. (John Zorn)

SLOWSCAN

Ralph Hocking, USA, 1981, videotape, b/w, silent, 4 min (excerpt)

This is an ingenuous and astonishing work made by s happily reclusive artist who has created many marvels in photography and video, often featuring his wife Sherry (often undressed), but who makes no effort to exhibit. A champion of the possibilities of “low res” video, he remains free of addiction to the technically latest and the most. For me, his brusque and unfussy video art remains the latest and the most. It’s an honour to present even this small example. (Ken Jacobs)

JACOB’S LADDER

James Otis, USA, 16mm, b/w, silent, 4 min

Jacob’s Ladder is a black and white spiralling, swirling computer-generated abstract animation. It combines its technological origin and its imagery (reminiscent of natural processes and objects – fractals, polyps, branching plants, crystal growth) seamlessly and beautifully.” (Patrick Friel)

UN PETIT TRAIN DE PLAISIR

Ken Jacobs, USA, 1999, Nervous System, b/w, sound, c.25 min

25 minutes to traverse, by train, (perpendicular view of) a single open Paris street. Remember the smooth rubber “spaldeen” (Spaulding), high bouncer that – sometimes in a stickball game on the once streets of Brooklyn – would split evenly along its circling seam? And then as pink twin hemispheres made possible further fun. What had been the secret interior was revealed to be so much cleaner and fleshy smooth than the exterior. Suggestively libidinal before one knew what was what. There was no point attempting to fling a half-ball; irresistible was the impulse to invert it ! Pop, inside out. The optical implausibilities of Un Petit Train de Plaisir inverts mentalities like pink half-spaldeens. (Ken Jacobs)

This performance was made possible by the generosity and co-operation of Frank Abbott and Nottingham Trent University. Thanks also Caroline Hennigan and Laraine Porter at the Broadway.

FURTHER NOTES

KEN JACOBS’ NERVOUS SYSTEM, WHAT, WHY AND WHEREFORE

The Nervous System places two identical film prints on two projectors capable of single frame advance and freeze. The twin prints step through the projectors frame by frame as dictated by the artist-projectionist, caught somewhere between movie and slideshow. They tend to advance slightly out of synchronisation, usually with only a single frame difference. Difference makes for movement and uncanny three dimensional space-illusions when a spinning propeller up front, between the two projectors, interrupts and alternates their cast images. Tiny shifts in the way the two images overlap onscreen create radically different visual effects. The throbbing flicker (avoid viewing if you have a history of epilepsy) is necessary to the creation of “eternalisms”, unfrozen slices of time, sustained movements going nowheres unlike anything in life. For instance, without discernible start and stop and repeat points, a neck may turn … eternally.

I enjoy mining existing film, seeing more of what film remembers, what’s missed when it clicks by at Normal Speed. Normal Speed is good! It tells us stories and much more but it is inefficient at gleaning more than the surface from the film-ribbon. And there’s already so much film. Let’s draw some of it out for a deeper look, toy with it, take it into a new light with inventive and expressive projection. Freud would suggest doing so as a way to look into our minds. We’re urban creatures, after all, huddled for warmth against the great outside, living in movies. We lie down on the couch and remember movies.

Illusion is what we recognise when we face facts, when we acknowledge the gullibility of our senses. Stage-tricks help reconcile us to our carrot-on-a-stick relationship to truth; the amusing illusion, seen as such, warns against delusion. A dose of formulated craziness can be refreshingly therapeutic! (see Hellzapoppin’, 1941). For instance: 21/2 D is hard to conceive. Things should either be flat or in depth. Yet the lit rectangle doubly cast by The Nervous System presents us with an impossible mix of the flat – our usual reading of forms reshaping as they slide across the screen, one with the screen, and the deep – here the screen punctured by the point formed by our twin sight lines, blown open, fragmented, its surface seemingly divided among myriad objects reaching forward and back of the actual screen-plane, and something in between, with both flat and deep claiming appearances unto their respective realms. Things get twisted, caught in this optical tug-of-war. It’s The Nervous System ! Putting the tangle into rectangle, and leaving it a wreck.

Not only things pictured but the rectangle itself gets caught in the struggle and becomes spatially unstable, advancing or sinking in depth, stretching or compacting, leaning tilting swinging rising falling splitting, peeling off the screen The rectangle, itself in motion, becomes a creature of time.

“Time / motion study” hardly suggests the exercise in ecstasy this can be. Or that we’re touching on the essence of cinema, its original impetus: vivisection of the moment. After a century of cinema industrialised, standardised, economically determined and “rationalised”, we need a return to the possibilities of a Cubist cinema (Cubism would’ve been unthinkable without the revelations of pioneering cinema). Opening fresh territory for sentient exploration, bringing spectacle forth from dross. Delving beyond the usual movie-message / cover-up to see the history that can be salvaged when film is wrested from glib 24fps.

Toying with light, with phantasm, can also open time to fantastic changes. Temporal illusions of another order from the expansions/contractions of Griffith and Eisenstein – too emotionally congenial to register as modernist derangement and delirium, trigger the transcendent (rather than escapist) function of art. Explain a time, for instance, in which things race forward, with bursting velocity, and yet don’t for a moment budge … without the projectionist-performer’s permission. Time arrested in the act, while remaining time, i.e. with things remaining in motion. Wheels turning forward may even travel backwards (impossible to imagine) at the whim of the cine-puppeteer.

Well, what moves the puppeteer? The very specific possibilities inherent to a particular strand of film. This frame times that frame equals… it’s anyone’s guess until discovery of the exact formula of projection adjustments makes it plain, allows it to happen, and often it’s an effect unique to that coupling; no two other pictures will do. Control, then, is a matter of attending very closely to what’s on the film. One tries this and that, but the givens of the shot, and their impact on the performer-projectionist, swing the action.

Closing in on (to allow the expansion of) ever smaller pieces of time is my inviting Black Hole. Actor’s faces can stun me with boredom (movies are about actors.) I confess to feeling walled in by human faces altogether, not as misanthropic reaction but because the human colonisation of human experience, in our urban lives, is so thorough. It is astonishing to find oneself here with so many others to chat with, but isn’t this essentially a search party with our work cut out for us? We’ve gotten caught in the makings of our own minds and the only way out may be to enter into the workings of the mind. Film as itself the subject of film is the spell we enter wide-eyed, so as to get a grip on and pull apart the fibres of the phantasm. Film study is our opportunity to lay out the mind in strips. So – big breath – if picking at the texture of cinema at the end of its filmic phase (reality retreating further as our cine-solipsism goes electronic) seems about as inward as one can get, it’s because the name of this digging tool I’ve devised, The Nervous System, also designates a main territory of its search, that place where we’ve blithely applied mechanism to mind willy nilly producing that development of mind known as cinema. Micro and macro worlds are equally “out there”. Divide (the moment) and conquer; advanced filmmaking leads to Muybridge and Marey.

(Ken Jacobs)

Back to top