Date: 12 February 2002 | Season: Andy Warhol Tate

THE FILMS OF ANDY WARHOL

12 February–24 March 2002

London Tate Modern & The Scala

A season of films to accompany the exhibition Warhol, at Tate Modern, 7 February – 1 April 2002, sponsored by UBS Warburg.

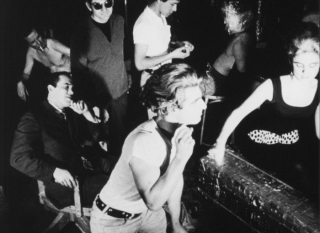

Though obsessed since childhood with Hollywood and stardom, it was not until the peak of his fame that Warhol turned his creative energy to film. During an explosive five-year period from 1963–68, he released over 60 films which range from silent, fixed-frame conceptual works through to contemporary commercial ‘sexploitation’ films. His reputation shifted from being the world’s most notorious artist to being the best-known director of ‘underground movies’.

Warhol’s studio, the Factory, was already a meeting place for New York’s artistic elite and underground subculture, and this mixture of high and low society provided a unique repertory of screen characters. Extroverts such Warhol’s assistant Gerard Malanga and the doomed socialite Edie Sedgwick, were brought together with members of New York’s avant-garde film and theatre movements to star in both improvised and scripted films.

The films have gone largely unseen since Warhol withdrew them from circulation in 1972 and this long-overdue season will be a chance to assess their cultural and historical significance. Rising from the fresh explosion of pop art, and crossing the boundaries of entertainment, conceptualism and the avant- garde, the films of Andy Warhol are first class art, and top entertainment.

The Films of Andy Warhol is curated by Mark Webber. With thanks to Callie Angell, Nina Caplan, Al Rees, Michael O’Pray and Silver Smith.

The films of Andy Warhol are distributed by the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Channel 4 will broadcast a new series of three documentaries on Warhol beginning 27 January 2002.

UNPUBLISHED TEXT ON WARHOL’S FILMS

Warhol’s films are shrouded in misconceptions – you might think you don’t need to see the films after hearing the title but that’s like having someone describe a piece of art and not seeing it for yourself. Seeing a still for a film, or a clip on television is like looking at a poster or postcard of a painting. Until you are able to directly engage with a work of art in the flesh, so to speak, you will never appreciate the qualities of the surface, its intention and depth. It’s lazy to regard Warhol’s films as ‘boring’ – they are vital and alive, with a resonance equal to his most impressive or well-known paintings. The confusion is compounded by the fact that the films have been seldom available for viewing. Like the greatest works of art, Warhol’s films must be experienced and engaged with; they succeed not only on an intellectual level but also as entertainment.

The films have a clear cultural and historical significance, rising from the fresh explosion of pop art, crossing the boundaries of conceptualism, entertainment and the avant-garde. The passage of time has revealed that Warhol’s stare was not one of benign passivity, nor was he a cold, hard manipulator. There is a keen eye for cinema, a remarkable ability to articulate a unique vision that sustains its ability to engage the audience. The films maintain the attributes of entertainment, whilst being artistic inquiries into concerns such as duration and representation.

Andy Warhol turned his creative energy to film in 1963, the year of his iconic paintings of Marilyn Monroe and Jackie Kennedy, and a time when his fame and notoriety was at its highest peak so far. He was an artist best known for seemingly mechanical, repetitious works, and recognised that cinema offered the opportunity to reproduce images 16 or 24 times per second. Since his childhood he had been obsessed with Hollywood and stardom, so it seems almost inevitable that he would want to produce his own films, and later range beyond the initial artistic context.

His studio, the Factory, had already become a meeting place for New York’s artistic elite and underground subculture, and this mixture of high and low society provided the repertory of characters from which he was able to populate his films. Natural extroverts from his immediate circle, such as his assistant Gerard Malanga and doomed socialite Edie Sedgwick, were brought together with those from the already active avant-garde film and theatre movements and were encouraged and empowered to appear in both improvised and unscripted experimental works.

During an incredibly productive five-year period, Warhol rediscovered the development and sophistication of film technique, progressing from silent, fixed-frame conceptual works through to contemporary commercial “sexploitation” films. His reputation shifted from being the world’s most notorious artist to being the best-known director of “underground movies”. Whilst his practise was rooted in the avant-garde, it’s important to assert that he was also drawing inspiration from Hollywood, theatre and documentary film.

After the assassination attempt by Valerie Solanas in 1968, Warhol soon withdrew from direct involvement in film production. Paul Morrissey assumed the directorial role of Factory Films, building on the box office success of the experimental double-screen film The Chelsea Girls, which had played in commercial theatres. Morrissey shifted the emphasis to producing more conventional movies such as the Flesh, Trash and Heat trilogy. Ironically, it is this work that has been screened most often while the true hardcore of Warhol’s cinema has remained out of view.

Andy Warhol’s films have a reputation based largely on a small but influential canon of writing, which itself dates mainly from around 30 years ago. The films have gone largely unseen since Warhol withdrew them from circulation in 1972. Even up to that point, few had been seen in England. After his death in 1987, the Andy Warhol Film Project was founded to research and restore this neglected area of his artistic output, and to make the films available again. Aside from sporadic screenings, there has been no real opportunity to re-evaluate or confront the films in the UK. This season offers a valuable chance to view a significant collection of works, and will surely demonstrate their lasting values.

Mark Webber, 2001

Back to top