Flicker Films

Date: 7 November 1998 | Season: Underground America

FLICKER FILMS

Saturday 7 November 1998, at 9:00pm

London Lux Centre

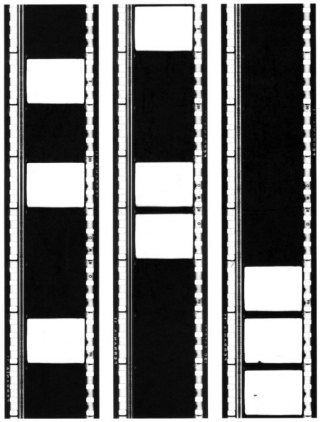

Not for the faint hearted – two hours of apparently empty frames! Unknown to the American artists, the Austrian film-maker Peter Kubelka developed his imageless portrait Arnulf Rainer in 1960. Five years later in New York composer Tony Conrad, artist Paul Sharits and theorist Victor Grauer each conceived their own flicker style by combining black and white, or colour, frames in rapid succession to give a strobe effect. Whilst these films can provide for enlightening viewing, members of the audience should be aware of their ability to induce epileptic seizures in susceptible people.

Peter Kubelka, Arnulf Rainer, 1960, 6 min

Victor Grauer, Angel Eyes, 1965, 10 min

Tony Conrad, The Flicker, 1965, 30 min

Paul Sharits, Ray Gun Virus, 1966, 14 min

Victor Grauer, Archangel, 1966, 10 min

Tony Conrad, The Eye of Count Flickerstein, 1966/75, 7 min

Paul Sharits, N:O:T:H:I:N:G, 1968, 36 min

Tony Conrad, Straight & Narrow, 1970, 10 min

WARNING: If you suffer from photogenic migraine or epilepsy you are not advised to attend this screening – as with stroboscopic lights, flicker films have been known to cause seizures or headaches for susceptible people. The intensity of the light from the screen, or the rate of flicker, cannot damage the eye but may possibly lead to discomfort or nausea. As a member of the audience, you are advised to proceed with caution, and to step outside into the foyer if you sense any ill affect.

PROGRAMME NOTESFLICKER FILMS

Saturday 7 November 1998, at 9:00pm

London Lux Centre

In the early 1960s, experimental filmmakers began to break cinema down into it smallest possible unit – the frame. Some went even further, removing any traces of image to present purely blank frames, whether in black and white or in colour. The Austrian filmmaker Peter Kubelka was the first to make an imageless film in 1960, believing that cinema speaks between the frames. In America, unaware of this achievement, Victor Grauer, Tony Conrad and Paul Sharits began to investigate the flicker phenomena. These four artists gathered for a symposium on “The Imageless Film” at the State University Of New York in Buffalo in the mid 1970s, and their films are reunited for this event.

Though Peter Kubelka began his cinematic career in Austria with Mosaik im Vertrauen (1954-55), he did not find a context for his art until he arrived in America in 1965. In this first film a series of images are grouped together using a set of highly developed rules. By Adebar (1957) and Schwechater (1958), he was severely reducing the amount of information in each frame. Adebar was originally commissioned as an advertisement for the Cafe Adebar in Vienna. Kubelka filmed dancers against a white wall to achieve a flat image with extreme contrast. He selected only a handful shots and carefully composed a structure using positive / negative juxtaposition and freeze frames. This film is one and a half minutes long, Schwechater is thirty seconds shorter and though similarly structured, it is generated from a more complex set of rules that are used to order only four images. It was commissioned by a beer company, who rejected it for commercial use. Kubelka recommends that viewers see each film at least twice before attempting to understand them. In Arnulf Rainer (1960) Kubelka completely removed the image by making a montage of black or white leader, accompanied by a soundtrack of white noise and silence. He considers it the absolute film, which both defines and brackets the art. The Viennese painter Arnulf Rainer commissioned a portrait, but Kubelka became interested in presenting film its purest form and again used a complex metric structure. For Unsere Afrikareise (1961-66) he travelled to Africa and recorded ten hours of sound and a few hours of visuals which he then studied, notated and memorised before editing the material into a twelve minute movie, abandoning single frame montage but concentrating on perfect image and sound relationships. Flawlessly assembled, it is regarded by many as his masterpiece. He made one further film, Pause! (1977), in which Arnulf Rainer himself finally made it onto the screen. Peter Kubelka was a founder member, and remains a director, of the Oesterreichisches Filmmuseum in Vienna.

ARNULF RAINER

Peter Kubelka, Austria, 1960, 16mm, b/w, sound, 6 min

“He has even created a film whose images can no more be ‘turned off’ by the closing of eyes than can the soundtrack thereof it (for it is composed entirely of white frames rhythming thru black inter-spaces and of such an intensity as to create its pattern straight thru closed eyelids) so that the whole ‘mix’ of the audio-visual experience is clearly ‘in the head’, so to speak: and if one looks at it openly, one can see ones own eye cells as if projected onto the screen and can watch one’s optic physiology activated by the soundtrack in what is, surely, the most basic Dance of Life of all (for the sounds of the film do resemble and, thus, prompt the inner ear’s hearing of its own pulse output at intake of sound).” (Stan Brakhage, New York Film-Makers’ Cooperative Catalogue #5, 1971)

Victor Grauer is a thereotician and composer who was one the first to present the flicker on film in the mid 1960s. These two early films have been rarely shown since that time. The original camera materials were recently discovered in his loft, and the filmmaker has struck new prints that will be premiered tonight.

ANGEL EYES

Victor Grauer, USA, 1965, colour, sound, 10 min

“Angel Eyes was probably the first color flicker film ever. It was made in 1965 and first presented at a screening organized by John Brockman at St. Marks Church, NYC. There was a lot of interest in this film (my first) at the screening, but I realized that this approach had the potential to be much more powerful and decided to make another with stronger ‘strobing’ effects (don’t forget, the strobe light was still pretty much unknown at that time). The new film, Archangel was made in 1966 and shown at the Filmmaker’s Cinematheque and, a bit later the same year, at the New York Film Festival (on the same program as Conrad’s The Flicker). Archangel attracted some interest and was shown in various other theaters in NYC. Early in ‘67, I left New York City to study music composition at SUNY Buffalo and was not able to continue my ‘research’ on imageless film until many years later.” (Victor Grauer, 1998)

Perhaps because of its eponymous title, The Flicker (1965) is probably the best known of all imageless films. It was made by Tony Conrad, a musician who became aware of the effects of stroboscopic light in a class at Harvard. After graduating he travelled to New York to study and play with the composer La Monte Young and found himself in the midst of the bohemian subculture. Through Young and his wife Marian Zazeela, Conrad was introduced to Jack Smith, for whom he assembled the soundtracks to Scotch Tape (1961) and Flaming Creatures (1962-63), and Angus MacLise, whom he recorded to accompany Ron Rice’s Chumlum (1964). With Jack Smith, Mario Montez, and others, Conrad also experimented with filmless films using the flicker of an altered 16mm projector as illumination (they were too poor to afford the stock, or the camera). In 1965, he used his mathematic training and the music theory on harmonic relationships he had developed with Young to evolve ideas for The Flicker. He borrowed a camera and shot a basic four thousand frames of raw material, which was then processed and compiled according to a carefully planned exposure timing sheet using approximately six hundred splices. The rate of flicker changes throughout the film to present a variety of harmonic chords which induce different sensations in the viewer.

THE FLICKER

Tony Conrad, USA, 1965, 16mm, b/w, sound-on-tape, 30 min

“I don’t think of The Flicker as a movie as we know it today. It is a piece of film that is experienced by a group of people in various ways – depending on how they choose to approach it. There is a variety of effects I am investigating, effects that act on your eyes so as to produce the actual imagery directly within the observer rather than in a normal way of having the eye interpret the light patterns on the screen. The film is actually divided into about fifty sections each of which consists of a repeating pattern made up of one rhythm of black and white frames. Nevertheless, most people see colors, and that is not unusual at all.” (Tony Conrad interviewed by Jonas Mekas, Village Voice Movie Journal, 1966)

In an extremely productive period between 1966 and 1968, Paul Sharits produced a series of outstanding films which, while devoid of mystical or cosmic imagery, seek to induce a change of consciousness by using relentlessly altering sequences of colour. His first, Ray Gun Virus (1966) was made while studying visual design at Indiana University and predates the introduction of sporadic images to his films, thus consisting only of ‘empty’ coloured frames. Sharits further disorientates the viewer by incorporating an amplified sound track of the film’s sprocket sounds.

RAY GUN VIRUS

Paul Sharits, USA, 1966, 16mm, colour, sound, 14 min

“Although affirming projector, projection beam, screen, emulsion, film frame structure etc. this is not an ‘abstract film’ / projector as pistol / time-colored pills / yes=no / mental suicide and, then, rebirth as self-projection / dedicated to Regina Cornwell” (Paul Sharits, Film Culture #65-66, 1978)

A year after Angel Eyes, Victor Grauer made Archangel (1966), a more powerful strobe film, which he described as “pure light energy, released by the splitting of the film atom”. Two further films, Seraph (“not for cowards”) and Certain Stars; Distant Star; Acid, were completed that year before he left New York City to study music composition at SUNY, Buffalo and was not able to pursue his interest in this area for some time. In the 1970s Grauer continued to investigate this phenomenon and made a number of computer generated flicker videos, and has more recently made what he regards as the definitive flicker work as a program for the Amiga computer.

ARCHANGEL

Victor Grauer, USA, 1966, 16mm, colour, sound, 10 min

“Whereas painting finds its true meaning in the articulation of space, the true meaning, the essence of film lies in the articulation of time. For this no image is necessary, only the alternation of light and non-light. It is presented in its simplest and strongest form when the contrast between light and non-light is at its maximum, i.e., when frames of the clearest possible film are placed in contrast with frames of the most opaque possible film, in a setting of total darkness”. (from A Theory Of Pure Film by Victor Grauer, Field Of Vision #1, 1976)

In 1966 Tony Conrad started work on The Eye Of Count Flickerstein, in which the flicker effect is seen as an intense sequence of images in the eye of the Count. Conrad does not regard the film as a successful achievement and it is no longer in distribution, so it is rarely seen today.

THE EYE OF COUNT FLICKERSTEIN

Tony Conrad, USA, 1966-75, 16mm, b/w, silent, 7 min

“Conrad’s second film, The Eye Of Count Flickerstein, begins with a brief Dracula parody in which the camera moves up to the eye of Count; then, until the end of the film, we see a boiling swarm of images very similar to, if not made from, the static on a television screen when the station is not transmitting. Aesthetically, Count Flickerstein lacks the ambition of The Flicker, but it is not without visual interest.” (from Structural Film by P. Adams Sitney, Film Culture #47, 1969)

In the same year, following the initial study of Ray Gun Virus, Paul Sharits made Word Movie / Fluxfilm 29 and Piece Mandala / End War (both 1966), in which at first words, then photographs were incorporated into the coloured flickers. His next major development was N:O:T:H:I:N:G (1968), a long flicker film which includes images of a chair falling backwards and a light bulb being drained of its energy. T:O:U:C:H:I:N:G (1968) came soon after and features the poet David Franks threatening to cut off his tongue with scissors and having his face scratched by a woman’s fingernails, while on the soundtrack his voice repeats the word “destroy”, which is looped into an unsettling mantra. In S:TREAM:S:S:ECTION:S:ECTION:S:S:ECTIONED (1968-71), moving images (a stream) and superimposition are introduced before the picture is systematically obliterated by scratches. During this period, Sharits developed his first double screen work, Razor Blades (1965-68), composed so as to bombard the viewer with forty-eight different images each second. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Sharits continued to be extremely prolific making complex and challenging films including Inferential Current (1971) Axiomatic Granularity (1972-73) and Episodic Generation (1977-78). In his lifetime, he was one of the few filmmakers who was successfully active in the art world. Between 1966 and 1973 he was a contributor to the Fluxus group. He also made Frozen Film Frames (complete filmstrips mounted between sheets of plexiglass) and developed several Locational Pieces (continuous installations for two to four simultaneous projectors, many of which were subsequently scaled down into single or double screen films). One of the most demanding of the Locational Pieces was Epileptic Seizure Comparison (1976), a double screen film comparing two male epileptics entering convulsive states, presented with quadraphonic sound in an enclosed, trapezoid space with metallic, reflective walls.

N:O:T:H:I:N:G

Paul Sharits, USA, 1968, 16mm, colour, sound, 36 min

“Based, in part, on the Tibetan Mandala of the Five Dhyani Buddhas / a journey toward the centre of pure consciousness (Dharma-Dhatu Wisdom) / space and motion generated rather than illustrated / time-color energy create virtual shape / in negative time, growth is inverse decay / dedicated to Stan Brakhage”. (Paul Sharits, Film Culture #65-66, 1978)

“The film will strip away anything (all present definitions of ‘something’) standing in the way of the film being its own reality, anything which would prevent the viewer from entering totally new levels of awareness. The theme of the work, if it can be called a theme, is to deal with the nonunderstandable, the impossible, in a tightly and precisely structured way. The film will not ‘mean’ something – it will ‘mean’, in a very concrete way, nothing.” (from a grant application by Paul Sharits, reprinted in Film Culture #47, 1969)

Tony Conrad was married to Beverly Grant, one of the underground movie stars, and in 1970 they began to make make films together. Straight And Narrow (1970) is a further development of the flicker principle, but introduces more visual information in the form of horizontal or vertical black lines on a white background. The film is immaculately constructed and is accompanied by a pulsating soundtrack by John Cale and Terry Riley. The Conrads also worked together on the feature film Coming Attractions (1970), a tantalising fusion of flicker and other optical effects with a narrative fantasy that stars Francis Francine. In their final collaboration they made the four screen abstract film Four Square (1971). Throughout the 1970s Tony Conrad totally deconstructed the normal concept of cinema. In 1972 he exhibited the Yellow Movie series of canvases painted with a yellow pigment that changed colour over time. He then developed a number of film performances such as Deep Fried 4-X Negative (1973) 7360 Sukiyaki (1973) and Roast Kalvar (1975) which involved the cooking of raw film stock. Bowed Film (1974) consisted of an amplified film loop running between the floor and his head. He also realised several versions of Film Feedback (1974), in which the exposed film comes constantly out of the camera and is immediately processed, dried and projected back onto the screen it is being filmed from. After spending several years concentrating on teaching and working with community television projects, Conrad has recently returned to music composition and performance.

STRAIGHT AND NARROW

Tony & Beverly Conrad, USA, 1970, 16mm, b/w, sound, 10 min

“Straight And Narrow is a study in subjective color and visual rhythm. Although it is printed on black and white film, the hypnotic pacing of the images will cause viewers to experience a programmed gamut of hallucinatory color effects. Straight And Narrow uses the flicker phenomenon … not as an end in itself, but as an effectuator of other related phenomena. In this film, the colors which are so illusory in The Flicker are visible under the programmed control of the filmmaker. Also, by using images which alternate in a vibrating flickering schedule, a new impression of motion and texture is created. The film is a tour-de-force in richness and variety of texture that can be achieved through very simple composition of minimal means (horizontal and vertical stripes) when they are controlled from frame to frame.” (Tony & Beverly Conrad, New York Film-Makers’ Cooperative Catalogue #6, 1975)