Peter Kubelka Speaks

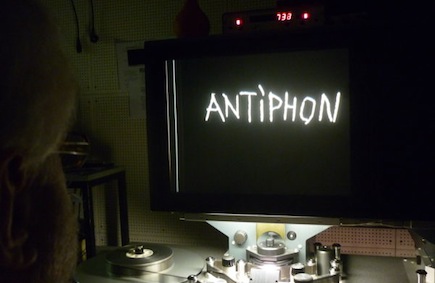

One of the unmissable events of this year’s London Film Festival is the extraordinary presentation of Monument Film by Peter Kubelka. Here, the veteran filmmaker talks to Mark Webber about aspects of his new work and the relationship between the films Arnulf Rainer (1960) and Antiphon (2012).

What are your memories of the premiere of your film Arnulf Rainer in Vienna?

This was in May 1960, in a rented projection room that was crowded with an invited public, maybe 250 people, and after the first screening there were 12 people left. I lost many friends with that showing but I was very happy because I liked the film, and it was something I had never seen before on a big screen. I can clearly remember Arnulf Rainer sitting on the back of a chair, looking glum, but at least he was one of those remaining. He expected a colour documentary of him painting, because I had shot imagery with him, which I then threw away. That event resonates with me very much now that I think of what is coming with the premiere of Antiphon. It’s not to say that I don’t care about people’s reactions, but whatever happens is fine with me.

When and why did you begin to think about returning to Arnulf Rainer to make Antiphon?

Now that the so-called “end of film” has appeared on the horizon, it became clear that 2012 is the black year where everything is being eradicated. This is the Waterloo of cinema. I wondered what I should do and I had the strong urge to make another film. Then came this disgust with the overwhelming flood of colour images in which we live, an imagery that falsifies my worldview. For me, the digital image looks like a pre-established publicity film, completely clean, sterile and shining. I don’t want to contribute a new work to this kind of imagery because I would not know how to escape these inbuilt qualities. So I lost all desire to make a film with images. I already felt like this already when I made Unserer Afrikareise, so on purpose I shot it on Agfa and printed on Kodak to get away from the Kodak taste and the Agfa taste.

What I had almost forgotten is that I’d already been thinking about the possibilities that are now being explored in Monument Film when I first made Arnulf Rainer, because of the idea of balancing of the film. I feel Arnulf Rainer very different from what many critics call it, namely violent. I feel it contemplative … and ecstatic at the same time. Just as Arnulf Rainer and Antiphon have this relationship of yin and yang, so contemplation and ecstasy belong together. In the new work Monument Film, ecstasy and contemplation are both there for cinema, it’s a film I tailored, or measured, to the body of cinema.

There’s also aggression, and tranquillity. At the time of Arnulf Rainer, I said I wanted to wash away the shit that normally appears on the screens, and today with Monument, I say ‘may it fly in the face of the digital.’ There is an aggressive mood but also I use it as a structure in which I hang myself and contemplate what is going on. The cinema situation is very, very precious to me, so I made this to honour it and called it Monument. I celebrate it and also I believe in a new birth, I think it’s strong enough that it will survive. The decision to do Monument Film this way was practically decided by this historical situation, and by my age – I know it’s late and this is what I wanted to see.

Could you elaborate on why you think 2012 is a pivotal year?

All over the world cinemas are being changed from material film toward machinery that uses the digital system. In my opinion, this is not a smooth transition; it’s an aggressive takeover by a completely different medium. As I have outlined before, this different medium has a completely different future and goes in another direction. Its destruction of the cinema is only a step of its life in evolutionary terms; it will just erase this and then go on to other things. The Pathé company force the cinema owners to destroy the classic film projectors, they even have to show photographs to prove that they’ve done it – it’s like Grimms’ Fairy Tales where the hunter has to bring back the liver of the person who is killed. So this is not just the installation of new machinery, there is an active destruction of what was there before. The film labs are of course going out of business, and Kodak is on the brink of bankruptcy.

Arnulf Rainer was conceived and made before you were able to see it, and similarly this is now the case with Monument Film because of the complications of double projection. You recently had the first test screening in Vienna – how did it live up to your expectations?

You could compare it to a composer of music. The composer ‘hears’ the piece in his mind but when it’s eventually played by an ensemble, it’s different again. I imagined that when the films Arnulf Rainer and Antiphon would be projected one after the other, that Antiphon would trigger these image/sound memories and play with that. I also imagined how Antiphon would look and sound, seen separate from Arnulf Rainer, and that was already very fascinating. There is no other film that could open such a door – you have to work with only light and darkness in order to establish these forms. Then the side-by-side projection is absolutely overwhelming. Everybody knows when you sit in the 1st or 3rd or 20th row, you have a completely different experience, and during the test screening I was able to see the film from various positions in the room. The third projection in Monument brings the space alive from whichever position you see it, and it amplifies Arnulf Rainer – suddenly the form dominates the space in an incredible way.

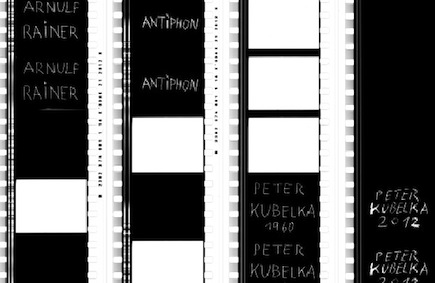

The final variation has both films projected simultaneously on one screen in the centre. When you project through the film, white overrides black. If the projector on the left is darkened by the film but the other projector is clear, the light is dominant. So you have continuous light over the whole length of the film but of course the light is not always the same – as you will see – it’s incredible how strongly the structure comes out. In the installation on the wall, with two prints placed on top of eachother, black overrides. It’s interesting that just as you have a yin yang relationship between the projection of Arnulf Rainer and Antiphon, you have a yin yang situation between the projection and the installation.

Working without seeing the film started earlier with Adebar and Schwechater. These were also made by hand, and this situation is unique – that you can make a film without an editing table, without a cinema – you can take it in your hands and scissors and make it without machinery. This is something that is very near to sculpture or painting, there is a body contact that creates a different way of thinking. Adebar was made at a time when I had nothing else in my mind but cinema, I walked around with these pieces of film in my pockets – I would look at them and imagine what I would see on the screen.

Is this why the installation of the filmstrips on the wall is an essential element of Monument Film?

Very simply, just as the film projection is very beautiful, for me, so is the installation on the wall. The installation is not a theoretical point I want to make in defence of cinema … although it is also that because it shows that film is also valid as a three-dimensional object and does not absolutely need to go through the projector. I feel absolutely that my films have a valid life in this form.

I first did this with Adebar in the 1950s. I was invited to a summer university in the Tyrol and when the film was projected, it broke. When I made the film from these elements, I already had this relationship of touching and looking through the strips, measuring the image and imagining the editing. Of course I always postulated that if a frame is removed from the film then the whole rhythm would break down. It’s like in a poem, you cannot take out a single word or a syllable or the rhythm collapses. So okay, the print was gone but then I took it out and pinned it onto wooden posts in the meadows. It was hanging there overnight and people would come to look at it, the film started to break in the weather and people took pieces home, it was a wonderful thing.

Peter Kubelka will present Monument Film in a unique lecture screening on Sunday 21 October 2012. A programme of Kubelka’s complete films will be shown on 11 October, followed by Martina Kudlácek’s epic portrait of the artist on 13 October.The Monument Film installation is in the BFI Southbank Atrium for the duration of the Festival.

Link to more info on PETER KUBELKA here

MONUMENT FILM screening :-

Sunday 21 October 2012, at 2pm, BFI Southbank NFT1