On On Venom and Eternity

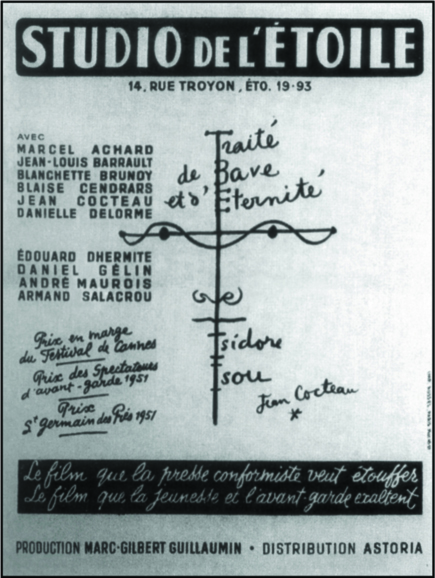

This year’s Experimenta Weekend begins with the screening of an incendiary film that, at the mid-point of the 20th Century, set out to be the turning point between film’s history and future. María Palacios Cruz discusses Isidore Isou’s Traité de bave et d’éternité (On Venom and Eternity).

“In true avant-garde fashion, it becomes something beyond itself. In as much as it is a formal exercise in filmmaking, it is a cinematic treatise on art, normalcy, society and culture”. (William E.B. Verrone)

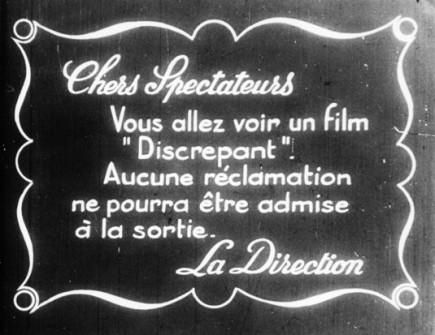

The first and only film by Jean-Isidore Isou, poet and founder of the French Letterist movement, constitutes a plea for cinema to enter into its second aesthetic phase. It is the manifesto of this new film era, which he calls chiselling (“ciselant”) and discrepant. The film begins with a dedication to the great cinematographic masters (Griffith, Chaplin, Clair, Von Stroheim, Flaherty, Buñuel, Cocteau …), that “contributed something new and personal to the art of film”, and with the filmmaker’s humble wish that his work will equally contribute to the advancement of film as an art form. Isou believed that cinema had come to an impasse at the end of its period of expansion and development, describing this “amplique” phase as a centrifugal force which must now be replaced by a centripetal one. Turning film towards itself, to its own deconstruction, he felt that film must become its own subject of observation and reflection – film as the object of film, ontologically and aesthetically, as well as materially. For Isou, the “amplique” and “ciselant” phases follow one other in all artistic disciplines, from literature to painting to theatre. By the middle of the 20th Century, time had finally come for cinema to become a truly modernistic art form, and to undergo a revolution equivalent to that brought by jazz to music.

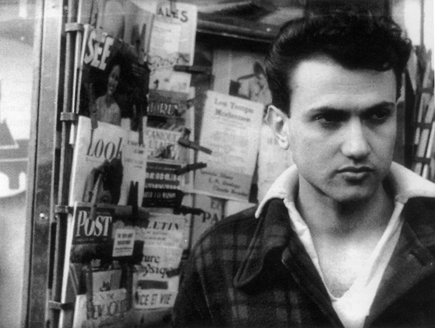

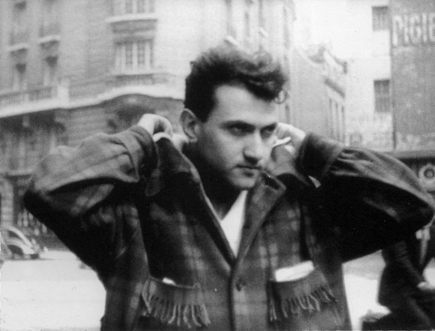

Traité de bave et d’éternité is divided into three chapters, all constructed following the principles of discrepant editing. Going beyond counterpoint editing, Isou seeks to fully dissociate sound and image, treating them as two “parallel columns” bearing no relation to one another. The first chapter introduces Daniel, the film’s hero and Isou’s alter ego. Daniel has just been to a screening of a Chaplin film and we hear an account of the heated debate that followed. This first chapter (“The Principle”) serves to announce the foundations and intentions of Isou’s manifesto, which in a mise en abîme will be put into practice during the two following chapters. In the meantime, we see shots of Isou walking around Bld St. Germain and neighbouring streets in the Quartier Latin. Our mind wants to bring some sense of coherence to the words we hear and the images we see, so we are tempted to imagine Daniel wandering in Paris after the film club debate. But during the second chapter (“The Development”) it becomes increasingly difficult to establish connections between the images (mostly found footage recovered from the rubbish bins of the Ministry of Defence) and the verbal account of Daniel’s romantic adventures with Eve, Denise and Mimi. The third chapter (“The Proof”) introduces Letterist poetry and brings an end to Eve and Daniel’s love story. The filmstrip is progressively scratched, drawn and manipulated, but unlike Lye or McLaren, Isou seeks no correspondence between the rhythms of the soundtrack and the scratches and etchings that cover the images.

“I want to separate the eye from its cinematic master: the eye”, says Daniel. With Traité – a film which demands to be heard rather than seen – Isou proposes a temporary disturbance of the hierarchy of our senses, sight becoming secondary to sound. Screening a work in progress version at the Cannes Festival in 1951, Isou didn’t bother showing any images for the second and third chapters, and only presented the soundtrack. Moving words instead of moving images. Nevertheless, the film was awarded the unofficial Prize of the Avant-Garde Spectators by a jury including Jean Cocteau, Curzio Malaparte and Raf Vallone.

The film’s image track underlines its emptiness and the destruction that cinema must undergo in order to be born again. For Daniel/Isou, “Vomiting up old masterpieces is the only way for us to manifest our originality, […] to create masterpieces of our own.” Isou makes use of the vomit – the venom – of commercial film production: abandoned, rejected, forgotten rushes found in the garbage, which are then subjected to scratching, bleaching and painting. The scratches create continuity between the disparate images of fishing, sport events, military parades, Paris … By destroying the filmstrip Isou intends to destroy the audience’s passivity, its desire of identification. He turns the spectators’ attention away from the image and onto the sound. He shows them that there is no longer nothing to see. Rejecting beauty in nature and art, Isou finds the possibility for a new beauty to emerge amid ugliness and putrefaction.

Traité would not be the preface to other film works that Isou conceived it to be, and remains his only completed film. A unique work, which announces in a quasi-premonitory way many of the preoccupations of the film avant-garde in the 1960s and 1970s, it remained largely unseen for many years. Stan Brakhage, who claimed to have been present at the North American premiere of the film in San Francisco in the 1950s, was deeply influenced by its vision, acknowledging its influence on all of his films. For him, Traité embraced the possibilities of the film medium, allowing a new feeling towards cinema to emerge.

María Palacios Cruz

Link to more info on ON VENOM AND ETERNITY here

ON VENOM AND ETERNITY screening :-

Friday 19 October 2012, at 6:30pm, BFI Southbank NFT3